Up, up and away: The Moon’s A Balloon ~ David Niven (Review)

.

Author: David Niven

Year: 1971

Publisher: Hamish Hamilton, London (first edition)

ISBN: 0-340-15817-4

.

From its outrageous teaser of an opening line to its final, tell-all confession, David Niven‘s The Moon’s A Balloon is a wonderfully wry, extremely keenly observed and utterly addictive read. Truth be told, it may just be the best autobiography ever written by a Hollywood celebrity – something it’s been heralded as ever since it was first published 40 years ago.

Compiled by Niven then when the prime of his career had passed (but a couple of years before the notorious incident he observed at, er, first hand while hosting the Oscars), it details the whole of his life – just short of the 12 further years he would live. And, truly, what a life he led; if any film star’s existence warranted a memoir it surely was Niv’s.

Born into an aristocratic family but quickly made fatherless owing to the First World War, Niven’s lissome Anglo-French mother was forever short of money, but made as good a fist of ensuring his and his (marvellously monikered) sister Grizel’s upbringings were as indulged as possible – which in the 1920s/ ’30s meant packing off her offspring to socially respectable boarding schools. This proved double-edged for Niv; arguably both the making and failing of him. While his early years and education at Heatherdown Preparatory School near Ascot and, later, Stowe School in Buckinghamshire instilled in him his unmistakeably polished, mannered, near fey, gentlemanly persona (thanks to which he’d go on to make millions), it also bred his wicked wit and clownish, anti-establishment side.

Indeed, owing to many pranks – for which he experienced a good few lashes – he missed out on a place at Eton (perhaps a blessing in disguise), spent several horrendous weeks at a cruel reform school and, following a stint of army officer training at Sandhurst, didn’t make the cut for his idolised Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, instead winding up in the far less prestigious Highland Light Infantry, who wore trew trousers rather than kilts. With this regiment he served – in a manner of speaking – for several years of little-to-no-martial-activity in Malta.

Perhaps because they were his formative years, the most entertaining sections of the book are these of his education and early army career. Full of rich detail, insightful observations and funny anecdotes on practically every page, these parts of the Niven story both acknowledge how blessed his upbringing and opportunities were, while pull absolutely no punches in pointing out how flawed a boarding school education can be, how staging hijinks with green beer was the only way to entertain oneself at a military outpost during the dying embers of the British Empire and how exciting, fulfilling and sad a tentative, tender, first affair with a Soho tart-with-a-heart prostitute was. Indeed, as opposed to coming off clichéd, Niven skilfully ensures these teenaged encounters with the aforementioned Nessie come off thoroughly heart-warming – indeed, they’re arguably the most touching moments of the entire book.

On fleeing the army for the States, Niven’s life would take a dramatic turn in the ’30s, featuring several surprising and most impressive entrepreneurial endeavours (among them cleaning rifles for hunters in Mexico and running an indoor rodeo racing venture with, yes, ponies), all of which are wonderfully regaled with both a fine balance of matter-of-fact honesty and a knowing nod to their improbability. As is his fledgling film career and rise from invisible extra, via risible actor, to bona fide Hollywood star. Niven, most certainly, affirms that there was much luck, as well as charming and schmoozing on his part, involved.

From his somewhat hell-raising bachelor days (during which time he shared a house dubbed ‘Cirrhosis-by-the-Sea’ with Robert Newton and socialised greatly with fellow Brit ex-pats like Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh), to his post-war highs of headlining the crazily realised yet Oscar-laden Around The World In 80 Days (1956) and unexpectedly winning an Academy Award thanks to his straight role in Separate Tables (1958), his Hollywood years prove a delightfully frank and insightful read – a warm and respectful but honest window then on to Tinseltown’s golden age.

But it’s the section of the autobiography that focuses on the Second World War, during which Niven genuinely earned his military stripes, that leaves you most impressed by the man. For no other reason than a stubborn duty to old Blighty did he give up his lucrative deal with Hollywood bigwig producer Samuel Goldwyn and board a boat back home following the outbreak of hostilities in September 1939.

He confesses that he visited the British Embassy in Washington before embarking, where he was advised to stay in America and not get involved until such a time as he may be called up. Predictably then, there followed a period of months when Niv couldn’t find a regiment that would take him. It’s a mark of the man’s calibre (and maybe that of his generation) that he was frustrated and desperate to get stuck in and sort out Hitler. How many civilians would genuinely seek to go to war today – even against the Nazis?

During his war years he was involved in the formation of the Commandos, took part in the June ’44 Normandy invasion, brushed shoulders with one Ian Fleming (whose first choice to play his later creation James Bond on the big screen was Niven) and dined with Winston Churchill more than once. Indeed, on one such occasion Niv recounts the greatly admired wartime PM telling him: “Young man, you did a fine thing to give up your film career to fight for your country. Mark you, had you not done so − it would have been despicable”.

Niven was lauded in his later years as a great raconteur, both in private and as a TV chat show guest, and this autobiography does feel like the literary equivalent of spending several hours in his company as he relates wonderful anecdote after wonderful anecdote. And yet it’s more besides. It’s the reporting of an interesting, charmed life well lived, with wit, sagacity and pathos springing from almost every paragraph. The first few pages of my edition of the book are taken up with approving quotes from many different reviewers, one of whom is Peter Sellers. Following some words of praise, Sellers asks the question “is there anything he [Niven] can’t do?”. After reading The Moon’s A Balloon, you’ll doubtless find yourself asking that very same thing.

.

So here’s to you, Mrs Robinson: far from a tight fit, The Graduate, featuring Dustin Hoffman and his seductress Anne Bancroft, is certainly on the list – but which other nine make the grade?

No question, Western society and culture went through dramatic changes in the oh-so notorious decade that was the 1960s. And no more apparent does that become than by looking at the movies it produced. Many of its best flicks reflected the growing sense of self-awareness, hope, disappointment, social and sexual liberation, excitement and conflict throughout Anglo-American culture and beyond. And some arguably went further – by influencing the culture that produced them. So then, as will be the case in posts to come for movies from both the ’70s and the ’80s, this very post details the dectet of cinematic gems that, for me, make up the list of the ultimate exponents of ’60s cinema. Here then, peeps, in no order but chronological, is my 10 films that could only have come from the ’60s – watch out because they ping, they sting and, yes, they most certainly swing…

CLICK on the film titles for video clips

.

À Bout de Souffle (Breathless) (1960)

So, as the opening flick on this list, what’s so special about the curiously named À Bout de Souffle? Well, it’s all about the French Nouvelle Vague or ‘New Wave’ film movement. Born out of the youthful exuberance and turmoil of the time, Nouvelle Vague was an artistic commitment to do the unexpected and different; to excite and stun. Not only did this flick do that with bells on, it also proved to be the one that broke the movement out of the Continent and into the UK and US – it was the film that turned Nouvelle Vague into ‘New Wave’. Filmed on the utter cheap by the now total legend but then debut filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, the movie was chopped down to its 90-minute running-time thanks to spontaneously created jump-cuts (cutting scenes halfway through). Further revolutionary touches contributed to its bold, highly visual, documentary-like style, ensuring that – to name just three and all of them ’60s classics – Tom Jones (1963’s Best Picture Oscar winner), A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and The Monkees-starring Head (1968) owed much of their look, feel, atmosphere and, well, entire point of being made to its cinematic advances. Moreover, ‘New Wave’ would influence and inspire filmmakers for years to come – well beyond the ’60s – as its techniques became assimilated into the mainstream language of cinema. Admittedly, to watch it, on one level À Bout de Souffle seems merely a French low-budget Hollywood noir take-off, but its title translates as ‘at breath’s end’ – that pretty much says it all.

.

Goldfinger (1964)

Let’s face it, you can’t get much more ’60s than a Sean Connery Bond film – and Goldfinger has to be the most ’60s of them all. The huge success of the first two 007 film adaptations Dr No (1962) and From Russia With Love (1963) may have paved the way, but it was this flick that established not just Bond, but ‘Bond And Beyond’ in ’60s – and wider – culture. In the wake of its unavoidable impact at the box-office ($125 million worldwide – that’s around $900 million in today’s money), Goldfinger unleashed ‘spy mania’ throughout the ’60s. On the box there were The Avengers (1961-69), The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (1964-68) and The Prisoner (1967-68), while at the flicks there were Our Man Flint (1966), Modesty Blaise (1966) and, in something of a retaliatory move, the oh-so obvious anti-Bond The Ipcress File (1965). And it all comes down to the iconography. Goldfinger simply was the coolest thing since James Dean died in a racing car. Both its look (all sleek, fantastical sets and smooth, sexy Aston Martins) and its sound (Shirley Bassey booming out the bombastic theme and John Barry‘s brassy score) ooze sophistication, sex, danger and aspiration. Both the UK and US consumer booms coincided in the ’60s and Bond – preserving Western capital as he did each escapade – was at their heart, an ice-cube in human form wearing a white tuxedo and flashing a killer smile as he sold an incredible, impossible lifestyle. Every man wanted to be him and every woman wanted to be with him. They still do – thanks most of all to this very film.

.

Darling (1965)

Ah, the Swinging Sixties. That short but irresistible era when the most fashionable of Britain’s youthful movers and shakers ensured that, back-slappingly, London was at the centre of the cultural universe. There were The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, the Mini, the mini-skirt, Jean Shrimpton, Twiggy, the 1966 World Cup win and the Union Jack emblazoned all over the shop and – seemingly – all over every shop. And there were also the movies. For every few breezy, switched-on Brit rom-coms like Georgy Girl (1966) or All Around The Mulberry Bush (1968), there was a real work of art that deconstructed the whole shebang – and the next three entries on the list are all prime examples of the latter. The first, Darling, is remembered as the launchpad for Julie Christie‘s magnificent yet enigmatic career (she won an Oscar for her terrific performance from it, beating herself in the same category for her turn in Doctor Zhivago, in fact), but the actual film itself oddly tends to be overlooked nowadays. Perhaps because it’s so close to the knuckle. Like with his later – and even more critically successful – Midnight Cowboy (1969), US director John Schlesinger concocted a caustic, bleak, cynical and all too honest account of the dark heart at the centre of a seductive dream a major city was selling, as Christie’s opportunistic model-on-the-make achieves all her materialistic dreams but finds little inner emotional satisfaction. Like Henry Cooper, Blighty’s most popular sportsman that decade, Darling pulls absolutely no punches – and is an absolutely essential ’60s movie.

.

Alfie (1966)

If Darling demystified the Swinging Sixties using a female protagonist, Alfie did exactly the same from a male perspective. Adapted from Bill (Cider With Rosie) Naughton’s stage-play, it’s an unapologetic, unfiltered exposé of one man’s exploitation of the sudden social, economic and sexual liberation the ’60s brought to Britain – and, ultimately, the consequences that neither advertising nor pop music of the time would ever admit unchecked carefree, philanderous behaviour wrought. An intelligent and informed part-‘kitchen sink’, part-sardonic sideswipe of a drama then, Alfie connected hugely with both the public and the critics; both groups adored Michael Caine for his triumphant ‘fourth wall’-breaking performance as the Cockney-about-town whose swagger is challenged and then some (following the success of The Ipcress File the year before, it was this flick that cemented Caine as a cast-iron star, as well as bringing him his first Oscar nomination). It also fuelled a storm, adding flames to the fire that was the debate of what an ever increasing liberal society was turning the country into. Away from all the clever stuff, though, a viewing of Alfie offers the viewer not just the sight of one Maurice Micklewhite on top form, but also of ’60s golden girls Jane Asher (then girlfriend of Paul McCartney), Eleanor Bron, Milicent Martin (from TV satire ice-breaker That Was The Week That Was) and Shirley Anne Field. Moreover, its unforgettable title song, composed by the incomparable Burt Bacharach, launched the career of Cilla Black. Short of a cameo from Bobby Moore, there simply ain’t stronger Swinging Sixties credentials than that.

.

Blow-Up (1966)

While both Darling and Alfie are arty takes on fashionable ’60s Britain, neither of them go the whole hog like Blow-Up – for this is Swinging Sixties cinema as art-house. Helmed by idiosyncratic Italian fimmaker Michelangelo Antonioni (who once accepted an Oscar with a single word: ‘Grazie‘), it brazenly shuns the sunny, optimistic feel of many Brit flicks of the period, instead embracing the darkness, confusion and nihilism prevalent of some. It’s a flick that primarily focuses on the notion of perception and reality, specifically with regards to an incident witnessed by its protagonist, a free-wheeling young photographer, which he suspects may have been a murder. So arty is Blow-Up, though, that one’s not entirely sure whether the perception/ reality theme extends to Antonioni wilfully lifting the lid on the Swinging Sixties or not; however, he had intended the main character – blatantly based on David Bailey and brought to life brilliantly by an oh-so cool David Hemmings – to be played by… David Bailey. Had that come off, well, that certainly would have played about with the real and the imagined of the era. The critics loved Blow-Up; it won the Grand Prix at Cannes and Antonioni was nominated for Best Director and Screenplay at the Oscars. Although, predictably, not received by the mass public as well as, say, Alfie, it was an immediate sensation among cineastes and those with their fingers on the cultural pulse – unsurprising given that it also featured early performances by ’60s icons Vanessa Redgrave and Sarah Miles, a nude appearance by fashion model Veruschka and music from jazz great Herbie Hancock and The Yardbirds (which ensured band members Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck made cameos). For all this, and its Soho and Chelsea filming locations, Blow-Up is an eclectic and essential artefact of Swinging Sixties art.

For more on Blow-Up, read my thoughts on its classic poster and this excellent blog post: http://doubleonothing.wordpress.com/2010/05/09/blowup-antonionis-seminal-60s-film-is-no-let-down/

.

The Graduate (1967)

Time to cross the pond now for an indubitable, unforgettable slice of ’60s cinema created by our American cousins. And what a slice – indeed, one may argue that The Graduate is such a great movie of the decade in question, it pretty much takes the entire cake. One of the biggest box-office hits of the ’60s (currently standing 19th on the inflation-adjusted list of all-time grossers in the US alone), it saw – perhaps predictably – students queue around the block to catch its tale of a young man confounded by and dissatisfied with the adult world into which he’s grown and for which his parents’ generation are seemingly responsible, so much so that he embarks on an affair with the wife (the eponymous Mrs Robinson) of his dad’s business partner, only later to fall fortuitously for her daughter. A work of satirical genius, The Graduate‘s sure-footed, caustic and – for the time – frank script and outstanding performances from its lead players (Anne Bancroft in an iconic role, Katharine Ross on charming, winning form and Dustin Hoffman in a star-making turn) is superbly complimented by a sometimes gritty and discombobulating visual style that owes a huge amount to ‘New Wave’ techniques. Jump-cuts, close-ups, zoom-outs, unconventional camera angles and millisecond-long flashes (one of Mrs Robinson’s naked breast – blink and you’ll literally miss it) are all employed by director Mike Nichols to underscore the film’s atmosphere of confusion, angst and agitation. The effect makes for an unusual but outstanding film, whose themes, ideas and, indeed, ending are still being debated to this day. Add into the mix a slew of timeless (and perfectly fitting) Simon & Garfunkel folk rock hits and you’ve got an unquestionably ’60s movie, but one so good and – like Goldfinger – rightly so revered, it transcends the decade of its creation.

.

If…. (1968)

By 1968, the Swinging Sixties were arguably over and hippiedom was being overtaken by youths rioting in the face of slow civil change and war in Vietnam. Plus, lest we forget, this year too saw the assassinations of both Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy. The ’60s then were suddenly, almost nightmarishly, giving way to angry confrontation and violence – and boy does If…. deliver that message. Instead of detailing youth revolt in an existential, comic manner like The Graduate, it goes for the jugular; the young ‘uns in If…. go properly rotten and rebel in far more tangible, physical and – ultimately – violent ways. A Palme d’Or winner at Cannes, If…. is a difficult watch. Many moments challenge the viewer’s tastes, ethics and morals; the sight of intelligent teenagers who buck a cruel, despotic private school system being humiliatingly caned for their efforts may disgust one, but the sight of the same teenagers waging guerilla warfare on that system come the film’s end (yes, really) must surely leave one wondering uncomfortably where their sympathies should now lie. Of course, this movie, working up as it does to that extraordinary finish, is an unashamed, unremitting parable of the society of the day – and the dangers its maker (counter-culturalist Lindsay Anderson) maybe feared were being fermented. But its arty – and, to be specific, surrealist – credentials aren’t just to be found in that bombastic finale. Equally surreal and intriguing is a black-and-white sequence in which protagonist Malcolm McDowell (who would go on to play a somewhat similar rebel in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 classic A Clockwork Orange) indulges in a sort of wildcat foreplay with a girlfriend-to-be, a sequence that foreshadows the animalistic conclusion. However, the thing that’s always pleased me most about If… is the presence of Captain Mainwaring himself, Arthur Lowe, in the cast – who’d predict that? After all, this is about as far away from Dad’s Army‘s cosy back-slapping of old-school British class and social institutions as you can get. The late ’60s, eh? They were strange days, indeed.

Read about If…‘s excellent poster-art here

~~~

Yellow Submarine (1968)

Can you really compile a list of the ultimate ’60s films without a Beatles movie on it? Well, all right, I may be biased as a big Fabs fan, but I don’t think so. However, I’m not going to take the easy option and plump for A Hard Day’s Night (1964) or even for its sequel of sorts Help! (1966); nopes, I’m going for the animated one, the one that was ‘for kids’, the one that doesn’t even feature The Beatles – well not until the very end, at least. Over the years, Yellow Submarine has become regarded as a real curate’s egg, even forgotten or disregarded by many casual film fans, but hey bull-y dog for them. For this flick is a rarefied gem of ’60s psychedelic art. Sure, it’s fair to say that as a ground-breaking pop musical (many of whose sequences prefigured the MTV-era video) and as colourful Swinging Sixties hokum, respectively, A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help! (1966) are time capsules of their eras, but neither quite go as far as Yellow Submarine. For, to watch this movie, it seems to sum up, nay define, the drug-influenced, fantastical diversions and affectations of the mid- to late ’60s. The fact it’s animated goes along way to ensuring this. Seemingly taking its look from Peter Blake’s historic album cover for The Fabs’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), it’s filled with a cornucopia of colourful characters (the Blue Meanies, Jeremy Hilary Boob PhD/ Nowhere Man and, of course, The Beatles themselves) and a slew of supremely surreal settings and sequences (Pepperland, the Sea of Time, the Sea of Science and the Sea of Monsters – the last of which features a vacuum cleaner monster). A box-office hit on release – especially with, yes, kids, turned-on teenagers and students – and a critical success too, Yellow Submarine not only delighted the mainstream, but also advanced animation techniques (the opening of Monty Python’s Flying Circus TV series owes much to it) and may just have been The Beatles’ favourite flick in which they appeared – now that’s what you call a recommendation.

Read a full review of Yellow Submarine by yours truly here

.

Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969)

Now, I’ll freely admit that Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice isn’t the best film on this list, but, peeps, this is a movie that’s so ’60s it aches. One may argue that Hollywood caught up with and addressed the decade’s snowball-like growing counter-culture rather belatedly – The Graduate only came in 1967 and Barbarella the following year. And in the decade’s final year, Tinseltown finally got around to addressing a small but growing trend among American (often West Coast) married couples eager to experiment in increasingly socially liberal times – namely, swinging or, to give its more chauvinistic but popular moniker back then, wife-swapping. Swinging, of course, would become more widespread in the ’70s (how widespread it genuinely did become then is open to question though, of course), but there’s no doubt that in the late ’60s among couples like Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice it was taking place – and, for once, when it came to the counter-culture Hollywood was on the button here. And like with other filmmakers on this list, director-screenwriter Paul Mazursky wasn’t sure he really like the issue he’d made his film about. His two couples are well-to-do 30-somethings with everything to lose if they sleep with each others’ partner, rather than teenagers exploring and pushing back the boundaries of social and ethical mores and because of that, cannily and pleasingly, hilarity ensues. Bob & Carol & Ted Alice then is a comedy, treating its subject matter as a ‘what if’ scenario rather than as social documentary in the manner of, say, Alfie or Darling, but despite – or perhaps because of – this softer approach it made a big splash with both the public and the critics and made stars of Elliot Gould and Dyan Cannon (both of whom received Oscar nominations for their efforts). Nowadays this film may seem a little tame, a little twee even, but for mainstream audiences of the time this was placing the ’60s under the microscope and examining them minutely – or at as minutely as they were willing to for an entertaining Saturday night out at the flicks.

.

Easy Rider (1969)

Unlike this list’s immediately preceding movie, its final flick has absolutely no interest in holding anything back as it presents an uncompromising view of the counter-culture that had spread across 1960s America. Easy Rider is as legendary as any movie you could name from that decade; indeed, perhaps more so than any other. For many, it will always be the ultimate ’60s film – and for good reason. Director Dennis Hopper and producer Peter – son of Henry and brother of Jane – Fonda (who together are credited as co-writers, despite much of it being ad-libbed on location) conceived the flick as a sort of modern-day western. Two societal drop-outs, one named Wyatt (as in Wyatt Earp), the other Billy (as in Billy The Kid), go looking for America on their hogs only to discover a confused, disconnected, disillusioned and ultimately violent land. What is Easy Rider about? Does it ask what has become of America? Does it ask what has become of the hippie movement? Does it ask where the hell are we all going? Or doesn’t it ask any real questions and is just a counter-culturalist road movie through the great open spaces of the United States? Well, the answers to those questions probably depend on your reading of it. What’s undeniable, though, is that once seen, it’s a movie that’s never forgotten and, thanks to its tone, style, music (Steppenwolf, The Byrds and Hendrix) and public impact, has become unconditionally wrapped up in the whole fabric of the 1960s. Moreover, like The Graduate before it, its wilful adoption of ‘New Wave’ techniques and – more so than the latter – its success as an avant-garde flick connecting with the mainstream, as well as its featuring of Jack Nicholson in his break-through role, ensured Easy Rider helped pave the way for the ‘New Hollywood’ era of the 1970s, when young, hungry filmmakers would take US cinema to new, exciting subjects, destinations and highs. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves, peeps – all that’s for a future blog post…

.

Five more to check out…

The Ipcress File (1965)

As mentioned above, the essential – and entirely intended – anti-Bond, with Michael Caine’s Harry Palmer a bespectacled alternative to 007

What’s New Pussycat? (1965)

Swinging Sixties rom-com romp-and-a-half scripted by Woody Allen and starring, er, Woody Allen, as well as the Peters O’Toole and Sellers, plus a gaggle of gorgeous girls

Barbarella (1968)

Jane Fonda is a sensational sex-kitten in Roger Vadim’s saucy, psychedelic space romp

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Stanley Kubrick’s über-ambitious, sci-fi ‘head film’, featuring a finale that has to be the ultimate trip – indeed, on some posters that very term was the tagline

The Italian Job (1969)

Michael Caine again, alongside Noël Coward, Benny Hill and red, white and blue (i.e. Union Jack-coloured) Mini Coopers, in the most swinging heist comedy imaginable – plus that ultimate cliffhanger ending

.

… And five great flicks about the ’60s

Shampoo (1975)

Warren Beatty tries to juggle affairs with both Julie Christie and Goldie Hawn as Nixon’s ’68 election success looms large in the background

Quadrophenia (1979)

Phil Daniels dons his parka and rides his Vespa to Mod oblivion to the sound of The Who

JFK (1991)

Myth and conspiracy theories collide with reality, as Kevin Costner investigates the assassination of America’s beloved President

Austin Powers: International Man Of Mystery (1997)

The sequel may contain the parody of Blow-Up‘s famous photoshoot sequence (sse above), but Mike Myers’ original ’60s spy movie spoof is the smarter, better and funnier flick

The Dreamers (2003)

Bernardo Bertolucci’s take on the May ’68 Paris riots, with lashings of nudity, sex and an irresistible Eva Green

Legends: Burt Bacharach ~ melody maestro

This girl’s in love with you: Burt Bacharach and film star wife Angie Dickinson lounge about in 1969 as he works on one of his pieces – another cool chart-topper, no doubt (Bettman/Corbis)

He goes by the faintly ridiculous, utterly brilliant moniker of Burt Bacharach, back in the ’60s and ’70s he was handsome, cool and mixed with – and married – Hollywood royalty, and he wrote and produced hit pop record after hit pop record. For those reasons, and those reasons alone, he’d probably deserve his place in the ‘Legends‘ corner here at George’s Journal, but what seals it, what really seals it, is the fact he’s also one of the greatest songwriters/ composers of the last century. In short, Burt Bacharach had it all. And that makes him a bona fide legend.

Yes, penner of more than 120 Top 40 singles in the US and UK combined, a hit Broadway musical, film scores to a handful of cinematic classics and a serious inspiration to everyone from Brian Wilson to Steely Dan and Noel Gallagher to The Last Shadow Puppets, Burt is a pop culture icon whose talent has formed an indelible and important slice of the soundtrack of the last 50 years. Oh, and of course he’s also managed to collect Oscars, Grammys and a trophy wife or two along the way.

He was born on May 12 1928 in Kansas City, Missouri, but was never a Mid-Westener, having been brought up in the affluent, tradtionally Jewish neighbourhood of Forest Hills in Queens, New York City. Unsurprisingly, Bacharach is of German-Jewish descent, the son of Irma (née Freeman) and Bert (yes, that’s right, Bert with an ‘e’) Bacharach, a syndicated newspaper columnist. At the age of 12, at his mother’s instigation, Burt started studying the piano; he also learnt to play the cello and the drums. Perhaps ironically, though, he far from enjoyed his piano lessons and wanted to become a professional American Football player – a dream he was never destined to fulfil given his lack of height and size (he would grow to be only 5′ 8” tall).

Although, in a sign that he’s always had an eye for the ladies, he put his talents to use by starting a band at school, as he realised it would be a good way to meet girls. With Burt on piano, the band achieved relative success, getting booked for local dances and parties. And it wasn’t long before the teenaged Bacharach caught the jazz bug. Thanks to a fake ID, he’d often sneak into 52nd Street’s bebop nightspots to watch and listen to legends like Dizzie Gillespie and Charlie Parker – their unconventional melodies and harmonies would leave a lasting impression on the young, enrapt fan.

Wishin’ and hopin’ (for hits): Burt and Hal David (l) and both with Dionne Warwick (r)

On leaving school, he enrolled at Montreal’s McGill University, where he took a music studies programme and claims he wrote his very first song, The Night Plane To Heaven. He then went on to study music composition at New York University’s Mannes School Of Music; the Berkshire Music Center (now the Tanglewood Music Center) in Lenox, Massachusetts; the New School For Social Research back in New York City (where he studied under the composers Bohuslav Martinu, Henry Cowell and Darius Milhaud); and the Music Center Of The West in Santa Barbara, California, to which he won a scholarship.

The first fruit of all this musical academic labour, though, was playing piano at Governor Island’s officers’ club and at concerts at Fort Dix, as he served in the army between 1950 and ’52. He was billed as a concert pianist at the time, mind, even if he was only playing and improvising pop medleys. Still, his first proper professional gig came thanks to meeting singer Vic Damone while serving as an army dance-band arranger in Germany. Upon his discharge, Burt became Damone’s piano accompanist and, around the same time, accompanied other vocalists in nightclubs and restaurants, one of whom was a young unknown called Paula Stewart. She became the first Mrs Bacharach in 1953, but their marriage was to last only five years.

In 1957, though, Burt got his big break when he was employed by Paramount Pictures’ Famous Music at the veritable pop song sausage-factory that was the Brill Building in New York, for it was here that he first met and first collaborated with, as Juno might put it, the cheese to his macaroni, lyricist Hal David.

Make no mistake, if it weren’t for Hal David, the story of Burt Bacharach would surely be very different. He almost certainly wouldn’t have been as successful; he maybe wouldn’t have made it at all. Why? Simple – Bacharach and David were made for each other. Of all of Burt’s partners, surely Hal was the most important of his life; professionally and artistically he certainly was. And their partnership was successful right from the off.

“There’s always been this need to give music labels, especially in England. If people want to call Walk On By easy listening then fine, call it that. But hold it up to the light and you see it’s not easy at all. I don’t know: maybe those songs have lasted because of that, because it was sophisticated at the time and I took chances.” ~ Burt Bacharach

Within just a year of writing together, Burt and Hal had not one, but two chart hits on their hands. The first, The Story Of My Life, was recorded by Marty Robbins and achieved top spot in the US country music charts; the second, the fondly recalled Magic Moments, sung by Perry Como, reached #4 on the main US chart, the Billboard Hot 100. As if that weren’t enough, both songs (admittedly, in this instance the version of The Story Of My Life was sung by Michael Holliday) became back-to-back #1 hits in the UK – ensuring that Burt and Hal became the first ever songwriters to achieve this feat. They were unquestionably, rather spectacularly on their way.

But almost as soon as they’d got started, Burt was prised away for an enviable assignment – between 1958 and ’61 he served as musical director on screen legend Marlene Dietrich’s stage tours across America and Europe. Even so, he still enjoyed hits in this period, including The Shirelles’ Baby It’s You (whose lyrics, incidentally, were co-written by Hal’s brother Mack).

And as the early ’60s progressed, so did Bacharach and David’s (Hal, again of course) pop compositions. One of which was The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), which somewhat oddly didn’t feature in the hit western of that year with which it shared its name, but was suggested to them as the title of a tune after the movie came out. That song was recorded by a young Gene Pitney, as was another hugely popular hit in the shape of Twenty Four Hours From Tulsa, released the following year. 1962 also saw the first recording of another standard-to-be, Make It Easy On Yourself sung by Jerry Butler, which reached #20 in the States, but when re-recorded by The Walker Brothers in ’65 hit #16 in the US and the top spot in the UK.

Indeed, Make It Easy On Yourself truly proved the ticket to make Bacharach and David a mint, as it was the song that, albeit indirectly, introduced them to the most prolific and enduring interpreter of their work, Dionne Warwick. Around this time, they were producing a lot of material for soul/ R&B all-male group The Drifters – Burt was also arranging horns and strings on their tunes – and it was at a Drifters session that they met New Jersey-native Dionne (who incidentally is a cousin of the much-later-to-be-famous Whitney Houston).

A backing vocalist back then, Warwick had a terrific ear for and ability to interpret their songs (navigating her way through Bacharach’s often complicated melodies and tempos like nobody they’d yet met) and had cut a demo of Make It Easy On Yourself. This, it seems, led her to believe that Burt and Hal would give her first dibs on the tune, not knowing they’d already promised it to Jerry Butler. Angry with them then, she apparently retorted ‘don’t make me over, man!’. They didn’t; in fact, the first song they did give her was named Don’t Make Me Over. Released later in ’62, it reached #21 in the US and was her first hit.

Having found Warwick, the floodgates now opened for Bacharach and David – if they hadn’t already. Over the next 10 years, they wrote 20 US top 40 hits specifically for or re-recorded by her, seven of which broke the top 10. And practically every one of those seven proved unforgettable: Anyone Who Had a Heart (1963, #8), Walk On By (1964/ US #6, UK #8), Message to Michael (1966, #8), I Say a Little Prayer (1967, #4), Do You Know the Way to San Jose (1968, US #10, UK #8), This Girl’s in Love with You (1969, #7) and I’ll Never Fall in Love Again (1969, #6).

And their successful collaborations with Warwick led to further – often just as – successful collaborations with other music artists at the top of their game. Throughout the ’60s, new and emerging singers made original Bacharach-David songs hits or made existing songs they’d written hits all over again and, with it, made themselves stars. How’s this for a roll-call? Dusty Springfield (I Just Don’t Know What To Do With Myself, 1963/ Wishin’ And Hopin’, 1964); Tom Jones (What’s New Pussycat?, 1965); Aretha Franklin (I Say A Little Prayer, 1968); Sandie Shaw (There’s Always Something There To Remind Me, 1964); Cher (Alfie, 1966); Cilla Black (Anyone Who Had A Heart, 1964/ Alfie, 1966); Herb Alpert (This Guy’s In Love With You, 1968); Adam Faith (A Message To Martha, 1964); Jackie De Shannon (What The World Needs Now Is Love, 1965); Manfred Mann (My Little Red Book, 1966); Bobbie Gentry (I’ll Never Fall In Love Again, 1969); Billy J Kramer and The Dakotas (Trains And Boats And Planes, 1965); The Fifth Dimension (One Less Bell To Answer, 1970); and, of course, The Carpenters with (They Long To Be) Close To You in 1970.

But just why were Burt and Hal’s songs so popular? Why did the public on both sides of the pond buy them up in the ’60s like they were going out of fashion (which they clearly, most assuredly were not)? Well, as a – if you will – sub-genre of the pop song, Bacharach-David compositions have over the decades come to be looked on as the epitome of ‘easy listening’ music. Now, there’s nothing wrong with that, you may say; but the labelling of their work in this manner has been arguably dismissive. Its laid-back, jazz-inflected, aspirational, frankly groovy sound was, back in the day, most definitely where it was at (if you weren’t a rebellious hippie or die-hard blues-rock man, that is). Yet, that type of sound, perhaps really because of its lesser competitors and imitators, soon was out of vogue – even derisively referred to as ‘elevator music’. And was that doing Bacharach and David a disservice? Was it ever.

Baby, it’s you: Burt was also a hit-maker with glamorous girls – with (clockwise from top left) Angie Dickinson at the ’69 Oscars, Marlene Dietrich, Carole Bayer-Sager and Jackie Onassis

The truth of the matter is that, like The Beatles and The Beach Boys at exactly the same time, Burt and Hal were pushing back the boundaries of the pop song. Thanks to the combination of Hal’s pitch-perfect, often full-of-longing lyrics (he sure could turn a phrase) set against Burt’s seductively smooth yet melancholic melodies, their ballads were utterly irresistible. Just listen to Twenty Four Hours From Tulsa, what with Gene Pitney’s outstanding delivery, its a three-minute epic paean to love lost in the face of love found. Now that’s what you call melancholia.

But the true genius of Bacharach-David’s work goes deeper still – thanks to the awesome, experimental talents of Burt the classically trained musician. Like the works of the great composers he studied and admired, Bacharach had total control over his tunes; he arranged, conducted and co-produced many of his hits – and practically all of the best ones. And, like Lennon, McCartney and Wilson, boy, did he experiment.

Unusual chord progressions, syncopated rhythmic patterns, frequent modulation, unpredictably changing meters and irregular phrasing appear throughout his tunes and, from a clever-clever musical point of view, are what make so many of them so damn good. One of many such examples is Anyone Who Had A Heart. In Bacharach’s own words, the melody of this song “changes time signature constantly – 4/4 to 5/4, and a 7/8 bar at the end of the song on the turnaround. It wasn’t intentional, it was all just natural. That’s the way I felt it.” This song also holds the distinction of featuring the first use of polyrhythm (two or more rhythms appearing simultaneously) in popular music.

And perhaps unsurprisingly, given Burt and Hal’s success and the former’s truly outstanding talent, pop songs alone soon weren’t enough for them – at least they weren’t for Burt. Owing to the circles in which he was now moving, Bacharach was hired by friend and Hollywood titan Charles K Feldman to write the score for the latter’s new film, the madcap comedy What’s New Pussycat? (1966), starring Peter Sellers, Peter O’Toole, Woody Allen and a menagerie of ’60s female sex symbols (the movie initially was to star Warren Beatty; deriving its title from the phrase Beatty used to answer the telephone). Not only did his involvement in the flick establish another string to Burt’s bow (film scoring), it also spawned another chart hit for him and David, the unforgettable song that shares the film’s name, sung by Tom Jones, and an Oscar nomination for Best Original Song.

“I feel fine about covers. I don’t feel fine if it’s a new song and the first time they hear it is somebody else’s arrangement. I’ve heard some great versions and some terrible and I’ve heard versions that top what I did. Say A Little Prayer is a prime example. I recorded it with Dionne and, even though it was a big hit, Aretha Franklin made a much better record. It’s not about the vocal, it’s about the way it feels.” ~ Burt Bacharach

As if underlining the fact Bacharach was now gravitating towards Hollywood, around the same time he met the film star Angie Dickinson and they fell for each other. So much so that she agreed to accompany him to London while he composed What’s New Pussycat‘s score. It was a whirlwind romance – ten weeks later they were married in a simple ceremony in Las Vegas, attended by a select few including Feldman (see husband and wife in a wonderfully cheesy Martini ad from the mid-’70s in the video clip above). Although Burt’s first film score had been for the cult ‘B-movie’ horror The Blob (1958), it was now that his association with Hollywood properly got underway.

Following his work on Pussycat, he and David came up with the title song for the Michael Caine-starring Swinging Sixties classic Alfie (1966) and he scored and – with David – provided the title song for less-than-successful comedy After The Fox (1967), featuring Peter Sellers and Britt Ekland. Then he provided the score and – with David again – the smooth-as-silk song The Look Of Love (performed mellifluously by Dusty Springfield) for the chaotic Bond spoof Casino Royale (1967). Produced by old friend Feldman, Casino Royale‘s production turned into a nightmare – it went through half a dozen directors – but turned a moderate profit and Burt’s brassy, playful score (including a marvellous title track performed by Herb Alpert And The Tijuana Brass) and the aforementioned The Look Of Love were all, well, loveable indeed.

So, if you’ve conquered pop music and movies, what next? Musicals. In 1968, Broadway producer David Marrick called on Burt and Hal to work with major playwright Neil Simon on a musical adaptation of the Oscar-winning Billy Wilder comedy The Apartment (1960). The result, Promises, Promises, was yet another hit – running for nearly 1,300 performances on Broadway before it transferred to the West End. It also won two Tonys, a Grammy for Best Cast Album and spawned the classic tune I’ll Never Fall In Love Again. But it was the following year when Bacharach and David were truly to hit the heights.

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid (1969) is a much-loved movie that’s remembered for many things: Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Katharine Ross, that unforgettable freeze-frame finish, the cliff jump, William Goldman’s wonderful, witty dialogue… and, yes, of course, Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head, performed by country-pop-crossover B J Thomas. Surely one of Burt and Hal’s most fondly recalled hits (US #1 for four weeks), Raindrops features in one of the film’s most fondly recalled sequences (Butch and Etta’s bicycle ride, see video clip below). For me, the marrying up of these two aspects – beautiful music and beautiful visuals – sums up the movie. It and Bacharach-David were simply made for each other. And the public (the flick, of course, was a huge box-office hit) and the critics agreed; the following year, Burt and Hal accepted the Academy Award for Best Original Song for Raindrops, while Burt alone also collected the Oscar for his scoring of the film, which although somewhat minimal was simply perfect film score work. No question, Burt was now on top of the world… on the downside, there was only one direction in which he could now head.

The break-up of Bacharach and David came in the wake of their work on the movie Lost Horizon (1973). Seemingly ill-fated all-round, the film was a musical remake of the 1937 Frank Capra classic, but ended up a commercial and critical disaster. The difficulty of the project led to acrimony between Burt and Hal and, following its release, the pair decided after 16 years together to go their separate ways. And the fall-out got worse. Owing to them not just being her writers but also her producers, as well as her being under contract to produce new material for Warner Brothers, Dionne Warwick decided she had no alternative than to sue them both for their split and, thus, effective split from her. This resulted in Hal suing Burt and the latter counter-suing the former. It was all very messy, as was, in fact, Burt’s personal life by now. For, owing to more than one affair he’d had over the years, his marriage to Angie Dickinson had hit the rocks. The second separation in this era of Bacharach’s life then came in 1975; he and Dickinson would formally divorce in 1980.

If the ’70s had been hard on Burt, though, things perked up considerably in the early ’80s. Not only did he remarry, but he also wrote a new chart-topper with his new wife, lyricist Carole Bayer-Sager (who had previously hit it big co-writing the song Nobody Does It Better for 1977’s Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me). Featuring on the soundtrack to the smash-hit Dudley Moore and Liza Minelli comedy Arthur (1980), which he also scored, (Arthur’s Theme) Best That You Can Do, performed by Christopher Cross, not only returned Bacharach to the US #1 spot for the first time in 11 years, but also won him (along with his new wife) another Oscar for Best Original Song.

Things were good again and Burt’s sound was most definitely back in vogue. As the decade progressed, he wrote hits for Neil Diamond (Heartlight, 1982, US #5), Roberta Flack (Making Love, 1982, US #13), Patti LaBelle and Michael McDonald (On My Own, 1986, US #1, UK #2) and Dionne Warwick – as well as Elton John, Gladys Knight and Stevie Wonder – (That’s What Friends Are For, 1985, Us #1 for four weeks). The latter was actually a cover of a tune first recorded by Rod Stewart for the film Night Shift (1982), re-recorded as a charity single that benefited the American Foundation For AIDS Research. It also, obviously, marked a reconciliation between Bacharach and Warwick.

The music industry and the styles and trends of the content it produced, of course, changed dramatically during the ’70s and ’80s, but by the end of the latter decade and into the next, Bacharach’s music – perhaps unexpectedly – began to enjoy what appeared to be a renaissance. Class may age, but will forever remain class. In August 1990, Scottish rock band Deacon Blue released a four-track EP entitled Four Bacharach & David Songs, featuring I’ll Never Fall In Love Again, The Look Of Love, Are You There (With Another Girl) and Message To Michael. The first of the quartet was released as a single and reached #2 in the UK charts.

The look of love: Burt’s face on Oasis’s Definitely, Maybe album cover (l), meeting Kate Moss and Noel Gallagher during Britpop’s mid-’90s high (m) and collaborating with Elvis Costello (r)

This wasn’t a rare blip, more chart-affecting proof that a new mood was calmly and – fittingly – smoothly spreading through the UK music scene, as melody-driven artists brought up on Bacharach-David began to assert themselves; their most successful exponents being the bands Swing Out Sister and, spectacularly, The Beautiful South. But it didn’t stop there, as the ’80s became the ’90s and British music found for itself a winning identity and/ or formula once more in the shape of ‘Britpop‘, Bacharach himself became a recognisable face for punters throughout the land again. Even if they didn’t actually know who he was.

Granted, Britpop was far more about swaggering rock music than melodic pop balladry (although, at its best, it was certainly satisfyingly melodic), but with the appearance of Bacharach’s face on the cover of monster band Oasis’s monster of a debut album Definitely, Maybe (1995), his relevance to the ‘movement’ was clear. For this was a direct reference to Burt’s inspiration on the songwriting of Britpop’s arguable leader, Oasis’s Noel Gallagher. Indeed, that inspiration became crystal clear when Gallagher later performed a live duet with Bacharach of This Guy’s In Love With You (indeed, the former admitted he stole elements of that song for his own song Half The World Way from the aformentioned album). Yet, in a decade so obsessed with retrospective – and in particular with ’60s culture – this labelling of Bacharach as influential (along with the likes of Lennon and McCartney, Jagger and Richards and Ray Davies of The Kinks) on the new music of the time, didn’t just make Burt relevant again, it made him cool again.

Was it any coincidence then that Burt’s music and, yes, he himself popped up in surely the most ’60s-retrospective-friendly movie of the era, the marvellously mocking spy hokum that was Austin Powers: International Man Of Mystery (1997)? Was it eccers like. The protagonist’s, a composite parody of Swinging Sixties icons, mantra may have been the out-moded ‘what the world needs now is love(-making)’, but the presence of Bacharach’s music and the man himself (see video clip below) reinforced that nostalgic, affectionate and – yes, even here – cool connection with the ’60s that the film strove to attain. And, let’s not forget too, that Bacharach-David tunes featured heavily the same year in the well received and watched Julia Roberts romcom My Best Friend’s Wedding, including a cast sing-along of I Say A Little Prayer.

“What really set it apart was its score … Bacharach introduced to Broadway not only the insistently rhythmic, commercial-jingle buoyancy of 1960’s soft-core radio fare, but also a cinematic use of Teflon-smooth, offstage backup vocals.” ~ The New York Times on the Bacharach-David musical Promises, Promises

In an occurrence that was seemingly kismet, it was around this time that I got into Bacharach (I loved Britpop, I loved Austin Powers and I loved Bacharach – they all seemed to fit each other) and it was also around this time that, riding the wave of this career resurrection, Burt decided to release a brand-spanking-new album – a collaboration with versatile musician Elvis Costello. Featuring something very much like the melancholic-melodic sound he produced with Hal David, the resultant album Painted From Memory (1998) was an absolute gem – in fact, for me, one of the best albums of the ’90s; a decade jam-packed full of great albums. Song after song on that record oozes smooth cool, complex melodies, jazzy pianos, flugelhorns and unapologetic romantic longing, all enhanced superbly by Costello’s searingly emotional vocals. If you haven’t heard any of it (you may have heard I Still Have That Other Girl, which won a Grammy), I seriously urge you to do so.

As the ’90s drifted into the ’00s and, indeed, up to the present day, Bacharach has both very much remained in the public firmament and made very firm his position as an iconic deliverer and innovator of pop music – sort of the chart ballad’s Mozart. Basically, he’s looked on and up to as exactly who he is for exactly what he’s done. Although, admittedly, his image now is less playboy songwriter, more avuncular pop godfather. Mind you, in 2005 he released the album At This Time, which came with self-penned lyrics, a collaboration with rapper Dr Dre and controversy thanks to its political message. Clearly, he still likes to mix it then. In his personal life, he’s remarried, had more children and lost a child (his and Angie Dickinson’s tragically troubled but gifted daughter Nikki, for whom he wrote a song in 1969 that became the theme to ABC’s Movie Of The Week on US TV).

But dare one say it, after all those years of success, all those following years in the relative wilderness, all those hits, all those downs both professionally and personally and both those comebacks in the ’80s and ’90s, yes, after all of that, one gets the feeling that Burt is now a man contented, perhaps like never before. He scaled the pop summit once, he did it a second time and now with a family happily around him once more (and friendships with his best collaborators renewed), he can look out on all he surveys with an air of satisfaction. Indeed, if that air were to be put to music, how would it sound? Cool, smooth, easy, yet complex and brilliant, of course. Because class may age, but will forever remain class.

.

Playlist: Ten of Burt’s best

CLICK on the song titles to hear them

Twenty Four Hours From Tulsa ~ Gene Pitney (1963/ US #17, UK #5 )

Walk On By ~ Dionne Warwick (1964/ US #6, UK #8 )

What The World Needs Now Is Love ~ Jackie DeShannon (1965/ US #7)

The Look Of Love ~ Dusty Springfield (1967/ US #22)

I Say A Little Prayer ~ Aretha Franklin (1968/ US #10, UK #4)

This Guy’s In Love With You ~ Herb Alpert (1968/ US #1 for 4 weeks, UK #3)

Do You Know The Way To San Jose? ~ Dionne Warwick (1968/ US #10, UK #8 )

I’ll Never Fall In Love Again ~ Bobbie Gentry (1969/ UK #1 )

(Arthur’s Theme) Best That You Can Do ~ Christopher Cross (1981/ US #1)

I Still Have That Other Girl ~ Elvis Costello (1998/ from the album Painted From Memory)

~~~

Further reading:

An insightful article on Nikki Bacharach and her autism (parentdish.com)

Playlist: Listen, my friends ~ August 2011

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and enjoy…

CLICK on the song titles to hear them

~~~

Dusty Springfield ~ Just A Little Lovin’

Henry Mancini ~ Two For The Road

Dick Van Dyke ~ Hushabye Mountain

Janis Joplin ~ Kozmic Blues

Love ~ August

Elvis Presley ~ In The Ghetto

James Brown ~ Something

Elton John ~ Someone Saved My Life Tonight

Cast of Bugsy Malone ~ Finale: Good Guys/ You Give A Little Love

Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark ~ Souvenir

David Bowie ~ Modern Love

The Dream Academy ~ Life In A Northern Town

Belinda Carlisle ~ (We Want) The Same Thing

Susanna Hoffs: Bangles Damsel

Talent…

… These are the lovely ladies and gorgeous girls of eras gone by whose beauty, ability, electricity and all-round x-appeal deserve celebration and – ahem – salivation here at George’s Journal…

~~~

Sweet, diminutive, coquette-ish and sexy as hell with those big brown eyes and holding her Rickenbacker guitar, Susanna Hoffs bewitched males the world over as she taught them how to walk like an Egyp-shi-an, then she seduced them when she ordered them to say her name, as the sun shone through the rain on her eternal flame. Or something like that. She’s the one from The Bangles everyone remembers and she still looks cotton-bloomin’ amazing – and, yes, she’s the latest addition to the Talent corner on this very blog…

~~~

Profile

Name: Susanna Lee Hoffs

Nationality: American

Profession: Musician

Born: 17 January 1959, Los Angeles

Height: 5ft 2in

Known for: Writing, playing and performing as vocalist for iconic ’80s all-girl band The Bangles, especially on the hits Manic Monday, If He Knew What She Wants, Walk Like An Egyptian (all 1986), In Your Room and, of course, Eternal Flame (both 1988). She also played the lead role in the film The Allnighter (1987) and appeared in the mock-band Ming Tea in the Austin Powers movies (1997-2002), directed by her husband Jay Roach.

Strange but true: On the ‘interesting’ advice of the producer, Hoffs actually recorded the vocals to Eternal Flame in the nuddy, owing to the former claiming Olivia Newton-John always did so.

Peak of fitness: Topping so many moments, including the cheekily flirtatious look-left-look-right moment in the Walk Like An Egyptian video (apparently the result of Ms Hoffs’ on-stage nerves), must be the scene in the aforementioned The Allnighter in which Susanna oh-so sexily slowly dances in front of a mirror while wearing, well, not very much at all. Hmmm, yes.

~~~

CLICK on images for full-size

.

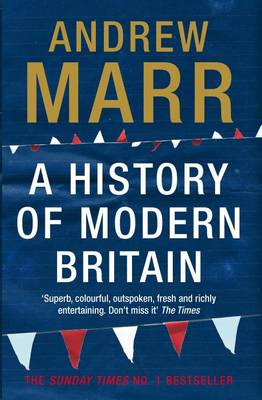

Author: Andrew Marr

Year: 2007

Publisher: Macmillan

ISBN: 978-1405005388

.

Make no mistake, Andrew Marr’s A History Of Modern Britain is a doorstep of a book. Boasting more than 600 pages, it’s an uncompromisingly ambitious, densely fact-filled and very long telling of the UK’s postwar story. But what a story – all the way from the welfare state-establishing Labour government of the ’40s to the Iraq War-mongering New Labour government of the ’90s and ’00s. And what a way to tell to it too.

For Marr kicks off his tome as he means to go on – highlighting the unexpected truth at the heart of the decision made in May 1940 (just after Winston Churchill had succeeded the failed Neville Chamberlain as Britain’s PM) over whether an arguably half-crippled Blighty should fight on against the German war machine or surrender to Hitler and seek clemency. The reality – a very little known one – is that of the five men of the war cabinet that had to make that decision that day, it wasn’t the usually ‘war friendy’ right-wingers who had traditionally ruled Britain (the Tories Chamberlain and the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax) who voted to carry on, but the left-wingers (Labour’s Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood) who, with Churchill’s decisive vote, did so. The two Tories voted to cut a deal; had they had their way, they would have seen the Nazis march into the country and probably finish off Britain, ensuring no modern story could even take place.

It’s exactly this unearthing of the unusual, surprising, delightful and even ironic throughout its tale of Britain’s last 50-plus years that is behind this book’s success. Attlee’s 1945 Labour government (despite its socialist agenda) can be thanked/ praised for turning Britain into a nuclear power; the ’60s’ telling legacy isn’t the peace movement or free love, but actually the triumph of modern consumerism; Thatcher at first wasn’t really that crazy about privatisation – they’re all here; this book’s full of ’em.

Indeed, anyone who watched BBC News about ten years ago will know that Marr (originally a Fleet Street hack with the likes of The Daily Express and The Observer) is a showman. His delivery of each night’s Westminster round-up as the Beeb’s political editor was full of theatrical flourishes; all lyrical turns of phrase and animated similes. He was a very populist sort of television newscaster and, rightly, became very popular because of it. And that impressively accessible style is to be found right here in this book. Brilliantly researched, unerringly focused, but an easy read – it’s both smart and light. Like many books of this sort, it’s best read by dipping in and out – and whenever you do so, it leaves you feeling more knowledgeable and more curious and often with a wry smile on your face.

Admittedly, you may not agree with all the conclusions Marr draws (the suggestion that ’60s/ ’70s troublemaker Enoch Powell was a more impacting politician than that era’s PMs – Labour’s Harold Wilson and the Tory Ted Heath – doesn’t really convince) and when he tries to summarise the complex, ever changing, youth-oriented culture of the ’60s in just six pages, he perhaps overreaches himself – more successfully he tries the same for merely the punk movement of the ’70s and doesn’t try at all for the popular cultures of the ’80s and ’90s. Yet one can allow him such oversights.

For, given the audacious aim of his book, he unquestionably brings to life the major events, ideologies, machinations and – most impressive and probably most important of all – the players behind Britain’s modern story. Yes, he manages to make many politicians appear interesting, intelligent, principled and full of personality. We have a dim, very cynical view of politicos right now (for good reason), so this genuinely is refreshing. For instance, his colouring of Harold Wilson as a sometimes paranoid, but often very clever ‘little spherical thing’ of kind of working class roots who presided over his cabinets by playing entrenched opponents off each other is one that will live with me forever.

If you’re at all interested in what this book’s all about, the political, economic, social and cultural history of postwar Britain, then you’ll no doubt have watched Marr’s BBC TV series that shared its name with this book. Fair dues, this very long read covers exactly the same territory as that terrific programme – and will probably take longer to read than that did to watch. But, in actual fact, this book was not the commercial companion to that series; in reality, Marr wrote the book first and, thus, wrote the series from the book.

Therefore, if you want the whole story, the real treatment not just the telly-friendly abridged version, then you have to give this book a read. If you thought the show was TV gold, then there’s many more nuggets mined here, just ready and waiting to be discovered and enjoyed by eager readers.

.

A History Of Modern Britain is available to buy here.

.

Playlist: Listen, my friends! ~ July 2011

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and enjoy…

CLICK on the song titles to hear them

.

Peter, Paul And Mary ~ Puff The Magic Dragon

Les Atomes ~ Michelle

Lindisfarne ~ Lady Eleanor

Frank and Nancy Sinatra ~ Life’s A Trippy Thing

Badfinger ~ No Matter What

Hawkwind ~ Master Of The Universe

The Raspberries ~ Go All The Way

Yvonne Elliman ~ Everything’s Alright

ABBA ~ Intermezzo No.1 (Instrumental)

Mike Post ~ Theme from Magnum P.I.

Mandy Patinkin ~ Younger Than Springtime

Jane Wiedlin ~ Rush Hour

Madonna ~ More

Some time in New York City: John and Yoko salute the Statue of Liberty in a moment from the video to the 1971 single Power To The People, filmed shortly after the couple’s arrival in NYC

About a year ago, the BBC screened – and I viewed and reviewed – Lennon Naked, a Christopher Eccleston-starring biopic of John Lennon’s life in London at the end of the ’60s, as he became reacquainted with his estranged father, endured heroin addiction and The Beatles broke up. And just last week, the BBC also screened and I also viewed what one may describe as, if you’ll so indulge me, something of a sequel to that made-for-TV-movie in the shape of the documentary Lennon: The New York Years, shown as part of Alan Yentob‘s Imagine art show strand. And, yes, peeps, I’ve also reviewed it – right here.

Lennon Naked concluded with John and his relatively new wife Yoko Ono leaving behind Britain and, with it, controversy, vilification and trauma, as they boarded a plane bound for a new life in the Big Apple, all blue skies and marshmallow-like happy clouds around them. However, as is made clear in this affectionate but fairly warts-and-all two-hour docu from filmmaker Michael Epstein (presumably no relation to the late Beatles’ manager Brian), that’s rather a rose-tinted view of the Lennons’ lives-to-come.

The decade that followed, in which they made New York almost exclusively their home, was far more troubled, tortured and turbulent than many may have assumed. In fact, it was a period that saw the couple fight against America’s establishment as they continued the youthful idealists’ call for universal peace, fought with its authorities in order simply to stay in the country and at times even fought each other.

The trouble started almost immediately. As the couple moved into the wilfully arty and unconventional Greenwich Village, welcomed by its musical crowd with whom they began collaborating in the studio and playing at militant and anti-war concerts, the Richard Nixon-led Republican government got decidedly twitchy – or, to be exact, paranoid. Hopelessly embroiled in the Vietnam War and no doubt worried about youth discontent – vocal like never before – what with re-election looming in late ’72, Nixon’s administration employed the FBI to monitor Lennon. This, to many who have even a passing interest in the former Beatle, is not particularly news. What may be, though, is that in an era when the political establishment was disconnected from the politicised – and mainly left-wing – young like never before and thus became overly anxious, is that it’s actually sort of understandable why the US establishment took such steps against Lennon.

Gimme Some Peace: Yoko and John emerge from an immigration hearing in New York City on April 18 1972 – John’s fight to stay in the United States would continue for the next three years

For, as this documentary makes clear, the anti-war leaders in America at that time explicitly engaged Lennon to become a mouth-piece for their movement through concerts and appearances in the wider media with the long-term aim of toppling Nixon at the next election and getting the troops out of Vietnam. And, given the success of the Lennons-led John Sinclair Freedom Rally at Ann Arbor in December 1971 (which led to the release of the counter-culture poet just three days later; Sinclair had been imprisoned for a total of 10 years simply for possession of marijuana), early on it may have looked like the Lennon factor could have some genuine impact.

As we now know, however, it was Nixon’s anxiety that the Democrats themselves would beat him at the polls and the attempts to undermine them, leading to the break-in at Washington’s Watergate hotel, that did him in. In fact, as the decade progressed, John had less and less to do with the anti-war movement, mostly because it lost traction itself, no doubt. Perhaps the pivotal moment here was Nixon’s re-election in November ’72, which was indirectly responsible for a pivotal moment in the Lennon story of the ’70s. So devastated by the election result (an extraordinary landslide for Nixon) was Lennon that he turned to drink. Indeed, disconsolate and drunk as a skunk when he arrived from the recording studio at a post-election party, he apparently picked up the nearest girl and noisily got down to it with her – in the full knowledge that Yoko and all his New York friends were in the next room, very much within earshot. Apparently, for Yoko’s benefit somebody had put on a Dylan record to muffle the noise, but to little avail.

By all accounts, John was literally prostrate with apology the next day (as is revealed in the film in a location photo taken that day for publicity of his new album Mind Games, in which he playfully and semi-seriously begs at Yoko’s feet). But real damage was done. In his words, his wife ‘threw him out’ – in reality, it appeared they agreed to spend some time apart; they’d spent the last two or three years around each other 24 hours a day, after all. So, John now jetted from one of America’s most iconic cities to another – Los Angeles.

In his first few days there, he seemed to relish both his newly discovered freedom and his new surroundings (sun, sea and the coital company of assistant May Pang – whose accompaniment had actually, rather bizarrely, been engineered by Yoko – agreed with him). He met up with former Beatles and – despite whatever anyone says – forever friends Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, as well as with Fabs favourite Harry Nilsson (singer of both Everybody’s Talkin’ and Without You) and enjoyed many a drunken evening.

Yet, after so many years of marriage – with both his first and second wives – it soon became clear that the bachelor life didn’t suit Lennon; in fact, it suited him as well as alcoholic stupors. And it was exactly one of the latter, one that lasted throughout the ill-begotten recording of his misguided rock ‘n’ roll covers album, er, Rock ‘n’ Roll (which took place at Hollywood’s A&M Studios in autumn ’73) that things came to a head. As recording footage included in the documentary makes clear, Lennon was drunk out of his skull during these sessions; surrounded by masses of musicians and verbally abusing legendary producer Phil Spector on the other side of the glass. The chaos and carnage (aided and abetted by the free-wheeling Nilsson) had to come to an end. Quite simply, Lennon had to return to New York.

This he did then, at the end of the year, and seemingly found himself immediately thrown into the recording of yet another album – the self-produced and more-than-decent Walls And Bridges. Actually, as he was still in the mood to make music, he pretty much had to do this, given Spector had oddly disappeared with Rock ‘n’ Roll‘s master tapes. Still, he got on with it, alcohol-free along with the rest of the performers as they recorded the album. A lovely moment in Epstein’s film regarding this period comes in New York-based DJ Dennis Elsas’s recollection of a September 1974 interview with Lennon in promotion of Walls And Bridges. Part of it can be heard here and, from it, one can can only agree with Elsas that the Lennon he met on this occasion was an amusing, laconic, lucid, relaxed and very amiable chap.

Indeed, although he would later recall the ’73-’75 period of his life as his ‘Lost Weekend’ (owing to him being separated from Yoko throughout these years), for much of ’74 it appears he was getting on with getting his music back on top. Proof of this can be seen in his grudging agreement with Elton John that he’d appear at the latter’s 1974 Thanksgiving concert at Madison Square Gardens and perform with him the Walls And Bridges single Whatever Gets You Thru The Night, so long as that single reached #1 in the charts. Of course, it did and, of course, Lennon kept his promise.

As Elton John recollects, a near petrified Lennon, who hadn’t performed on-stage for years, threw up in the toilet before going on, but went down a storm (see video above). Plus, lest we forget, it was at the end of this concert that he met up with and eventually reconciled with Yoko. Does Elton feel responsible for this reconciliation then? A rather humble Elton in the film – despite wearing glasses with ‘EJ’ emblazoned in a corner of one lens – says he certainly doesn’t, but touchingly seems pleased to have (in)directly played a part in it. Bless him.

Silver dream pacer: John and Yoko taking a stroll in Central Park in a publicity shot for the Double Fantasy album, taken on November 26 1980 – less than a fortnight before his death

As Lennon’s ’70s story slides into mid-decade, it becomes less congested. Mostly owing to the birth of his and Yoko’s son, Sean, on October 9 1975. However, that very date proved a momentous one in this story, given that not only was it John’s 35th birthday and the day of his second son’s birth, but also coincided with the dropping of the case to boot him out of the country. Hounded by American immigration ever since he first landed in the USA (owing to Nixon and co.’s original vendetta against him and continued after the latter’s fall due to the authorities’ thoroughness), Lennon had amazingly been living on a visa that only lasted for 60 days at a time. Indeed, on one occasion in the early ’70s he heard he supposedly had to leave the country on the radio while sitting in a taxi cab – allegedly wisecracking to the driver: ‘Take me to the airport, Sam’.

In the end, then, he won his case and, according to his former lawyer, did so partly because the judge dealing with the issue was a fan of his – and believed that the singer’s struggle to stay in the USA was reflective of America’s own founding principle of freedom. Lofty philosophy perhaps, but as the lawyer reflects, rather heart-warming in its way.

Moving towards middle-age and with less hunger to make music and top the charts (he’d been at it for nearly 20 years, after all), Lennon now withdrew from professional and public life and effectively became a house-husband. Of the two parents it was he who spent the majority of the time with his new son rather than his wife, it was he who did the majority of the cooking and it was certainly he during this period who wanted to spend quality time with his second son given he hadn’t with his first. As one may guess – and as the documentary suggests (with help from archival footage of Lennon speaking) – there’s little doubt an older, perhaps wiser Lennon found more balance and happiness in his life during this slowed-down, toned-down period. Actually, check out the wonderful Watching The Wheels from 1980’s Double Fantasy album; it pretty much spells this out.

Sadly, the film naturally has to finish on the sour, moving note of its subject’s death at the end of this self-imposed retirement, just as the artist had returned to making music and was on the verge of releasing it to the public again in the shape of Double Fantasy. Yet, in reality, it feels like more of a bittersweet note, for by this stage in his life, Lennon was surely a man at peace (both with Yoko and without); delighted at merely being able to walk into a shop and buy a nice (er, silver) jacket like a non-celebrity and happy that his music had become ‘MOR’ instead of trend-setting (he was now middle-aged just like his likely audience: ‘how’re you doing? how did your relationships turn out?’ he proffered as a question his new album may pose them).

So, yes, it’s tragic he was taken from the world at a point when he was – perhaps for the very first time – genuinely happy, but at least when he went he was content after all the difficult and dramatic, troubled and trauma-filled years with both the Beatles and those that followed in New York. Just listen to (Just Like) Starting Over (below), go on, and say that ain’t so.

.

John Lennon: The New York Years isn’t available to watch again on BBC iPlayer, but check the programme’s official page to see if and when it is, as well as when it’s next screened in the UK and Northern Ireland.

Still looking good: another roster of rare movie posters

Not to big up this blog of yours truly too much, but one of its most popular posts has been an effort I put together last September featuring 20 of my favourite rare film posters. Well, in that great (and, admittedly, sometimes not so great) Hollywood tradition of the sequel, I’ve decided with this very post to repeat the trick.

So, here follows, mes amis, a score more of – to my mind – terrific but too little talked about, pored over and purchased movie posters of lore. Unlike last time out, most of the examples of this collection are grouped together by genre, theme or poster artist – not because I’m trying to go too arty on you all, you understand, but merely to try and better highlight why methinks they’re such damn good posters. Anyhoo, enough with the waffle; on with the perusal…

.

CLICK on the images for full size and on the film titles for more information

~~~

Return Of The Jedi (1983) ~ for USA market (unused artwork)

(Above)

Wait a tick, there wasn’t ever a Star Wars movie called Revenge Of The Jedi, was there? Yes, peeps, our opener this time is a real teaser of a would-be teaser poster. You see, Revenge Of The Jedi was the ‘working title’ for (as the poster suggests, if you look at the line of type at its bottom) 1983’s Return Of The Jedi. Quite the rare piece of film publicity this then – but a real goodie too. This ‘un, methinks, is a great exponent of the use of watercolour on a movie poster (when do you ever see that nowadays?). Only a watercolour could produce that wonderful splash, or even explosion, of light in the bottom right-hand corner – ostensibly created by the duelling lightsabers – suggesting the epic, nay operatic, clash between good and evil (or, to be specific, Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader) that would await us in this final instalment of Star Wars‘ original trilogy. Classic stuff, indeed.

~~~

Judgment At Nuremberg (1961) ~ for USA market/

A Bridge Too Far (1977) ~ for UK market

Often there’s no better way to sell a product than by using a famous face – and these two posters do that with bells on. Frankly, given the fact their respective flicks feature casts absolutely bulging with Hollywood heavyweights, why the hell not? The better of the two surely must be Judgment At Nuremberg‘s; the starkly white but very familiar faces in profile on a simple black background not just creating a striking image, but also nicely reflecting the dark sombre subject matter of the movie (the post-WWII Nazi war crime trials). A Bridge Too Far‘s poster then isn’t a classic and is pretty blatant in selling its film on the strength of its stars by featuring mugshots of them in character (indeed, its alternative parachutes-landing-on-a-pink-backgound version is probably more satisfying), but for me there truly is something charming about its shameless selling – I mean, back in ’77, how could you have not wanted to see an epic war film with all the guys this image purports are in it?

~~~

Dr. Who And The Daleks (1966) ~ for UK market/

Thunderbird 6 (1968) ~ for UK market