Don’t pass this by: Happy 70th birthday, Ringo Starr

Close and some cigar: Ringo shows who’s boss as he poses in front of 10 Downing Street with a big fat stogy at the height of his Beatles fame

Yes, that’s right, one of rock ‘n’ roll’s most famous sons has reached his three scores and ten years today. Ringo Starr. Richard Starkey. That one who got a huge ring stuck on his finger in the movie Help. While some cruelly suggest he wasn’t even the best drummer in that rather famous band he played with, it’s undeniable he’s an utter legend in his own lifetime – and for all the right reasons.

He was always the most loveable, carefree and- maybe – most accessible of The Beatles (a bit like a big Liverpudlian teddy bear); married a gorgeous fan in the shape of Maureen Cox and then married a Bond Girl, the drop-dead beautiful former model Barbara Bach (Major Anya Amasova or XXX in 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me), gave arguably the best performances of all four Fabs in their two iconic films A Hard Day’s Night and Help; and sired another top drummer in son Zak Starkey, who has played with The Who in recent years.

“Ringo was a star in his own right in Liverpool before we even met. He was a professional drummer who sang and performed and had Ringo Starr-time and he was in one of the top groups in Britain but especially in Liverpool before we even had a drummer. So Ringo’s talent would have come out one way or the other as something or other. I don’t know what he would have ended up as, but whatever that spark is in Ringo that we all know but can’t put our finger on — whether it is acting, drumming or singing I don’t know — there is something in him that is projectable and he would have surfaced with or without the Beatles. Ringo is a damn good drummer.” ~ John Lennon, speaking in September 1980

Starr’s post Beatles career hasn’t received anything like the critical acclaim his work with John, Paul and George did – which included vocals on With A Little Help From My Friends, Yellow Submarine, Act Naturally and the three tunes he was involved in writing or penned himself, Don’t Pass Me By, What Goes On and the seemingly universally loved Octopus’s Garden. However, over the decades his own music has developed a strong – and often cult – following, and Ringo himself has ever remained a hugely popular figure the world over. In 2006, following a campaign staged by a British tabloid, he claimed he didn’t want a potential knighthood, but instead wouldn’t mind being made a duke or a prince.

So, here’s to Duke Ringo of Starrdom, 70-not out and still a force for good, old fashioned peace and love. Go on, give the old ‘V’ sign a go right now now and do the man proud – it is his birthday after all…

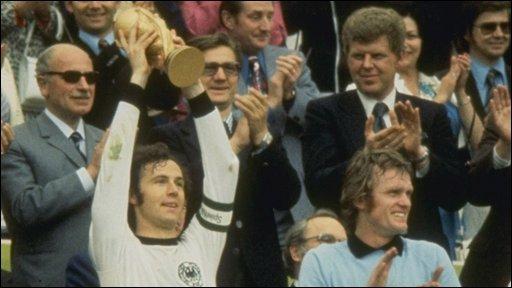

Cheat it: Diego Maradonna’s moves were even better than Michael Jackson’s, but when talent failed, cheating sufficed – no surprise as what was really on Argentina’s mind was revenge

Ah, 1986. The year when ill-starred Royal couple Andrew and Fergie married, when Crocodile Dundee showed New York lowlifes what a real knife was, when the space shuttle Challenger exploded in mid-air, and when the 13th World Cup took place in Mexico. The 13th? Yes, that’s right, this tournament – and especially its most memorable match (around which this sixth World Cup special here at George’s Journal will pivot) – certainly proved to be lucky for some, unlucky for others.

However, the all-important need-to-know background to this competition and, in particular, this match dates back another five years, to 1981. And, in part, it involves a figure familiar to followers of a past World Cup blog from yours truly. Yes, our old ‘friend’, General Jorge Videla, self appointed tyrant of Argentina; but don’t worry, it genuinely only involves him in part. That’s because it was in 1981 that the Argentine power at the top switched from Videla to another general, Roberto Viola, and, in turn, later in the year, the military junta that ruled the country was replaced with another, resulting in its third army dictator in succession, General Leopoldi Galtieri. Unfortunately, though, Galtieri was quick to become as infamous on the world stage as Videla. And it was all because he turned his attention to a small group of islands in the South Atlantic.

Economically depressed and suffering from civic unrest, Argentina was under the kosh in the early ’80s and this latest ruling junta was feeling the pressure. So, well aware of its country’s longstanding claim of sovereignty over the nearby Falklands Islands, South Georgia and Sandwich Islands, in spring ’82 the Galtieri government took the decision to invade the islands – first with civilians, then with soldiers – and raise the Argentine flag on South Georgia. This it decided, although potentially leading to war with the the UK (not only owner of the islands, but internationally recognised as such), would stoke up patriotism among the Argentine population, turning its head away from the nation’s domestic problems and lend legitimacy and room for manoeuvre to the new junta. It was an interesting and, ultimately, doomed gamble. For what Galtieri and his cohorts had not counted on was the fortitude and resilience of Britain’s leader, PM Margaret Thatcher.

Relatively new to power herself, Maggie was not yet the immoveable object, let alone the ‘Iron Lady’, political legend has since cast her as. With her deeply unpopular and drastic economic policies beginning to take effect on the UK (tackling inflation, but raising already high unemployment levels), the majority of Britons’ verdict on Thatcher was out; she was far from assured a second term as leader when she would go to the polls – in either ’83 or ’84. However, the Falklands War changed all that.

In love and war: the Mexico ’86 logo (left); Pique, the funky World Cup mascot I adored when I was six years-old (centre); and the Falklands War – serious business back in ’82 (right)

Seizing her opportunity, as the great opportunist she was, she threw all the British armed forces had at the Argentines (army, navy, air force and the SAS) and won the thing within 74 days. Despite 257 losses, Britain’s victory was comprehensive (there were 649 Argentine losses – including 321 on the sunken Belgrano ship alone) and her status as perma-strong, patriot leader was established and her re-election the following year assured – she received a landslide vote. Galtieri and co. were less lucky. Fallout from the Falklands defeat in Argentina saw his junta toppled and, mercifully, democracy swept in to fill the void. Yet, this was still a nation that had lost a war; its national pride had taken a fall. At the hands of the British then, a new wound had been opened in Argentina and the country was hurting…

Four years later in June ’86, though, and it was all smiles. Following South America’s Colombia having to pull out as host, the latest World Cup had instead kicked off up in sunny Mexico, which had been the stage for the classic 1970 tournament – surely a good omen. The world, then, awaited yet another fun-filled festival of football. Well, not just the world, but me too. Yes, at the tender age of six, as I was, this was the first World Cup of which I was aware. Now, I’ll admit, at this blissfully innocent and wonderful point in life I was more interested in catching The Flintstones each evening after the children’s telly had finished on BBC1 (Neighbours wouldn’t fill this slot until later that summer), than I was in keeping abreast of what was going on in the greatest sport on earth’s greatest and latest competition. However, when one day I happened to turn over to ITV instead of watching The Flintstones, I was faced by those two former cornerstones of TV football, Liverpool legend Ian St. John and Spurs supremo Jimmy Greaves, otherwise known as Saint and Greavsie, as they presented their early-evening report on that day’s World Cup goings-on – and thus my introduction to televisual football took place.

Not to say footy on telly and me were a perfect fit immediately, though. This sport seemed a very grown-up and rather rough and tough entity, quite the intoxicating thing to my young mind – a bit like pubs. Not surprising perhaps, considering this was the era of hooliganism; football was some way from the family-fiendly status it’s enjoyed in modern times. In short, I couldn’t quite fathom it. Yet, at the same time I totally grasped the inherent appeal of it – as do many when they first encounter football at the time of a World Cup. Unquestionably then, footy had lit some sort of flame in me; and, no doubt, that had something to do with the fact that, once again, England were taking part.

Setting the pace: the Danes (left) and the Soviets (right) show exciting, surprising early form

Unlike in the previous tournament, but like so many before and since, the English got off to a far from auspicious start. Their first group game against Portugal resulted in a 1-0 loss, their second against Morocco was arguably just as bad, ending 0-0 – yes, they may have gained a draw from it and therefore a point, but through it they lost to a dislocated shoulder their now captain, the utterly rambunctious Bryan Robson, and to a silly red card their vice-captain Ray Wilkins. Looking a busted flush already, former Ipswich manager Bobby Robson’s side required a re-shape… and a miracle.

“We were getting pilloried back home, which is the norm when England don’t start particularly well. But we weren’t really aware of it at the time. We were cocooned in our hotel without any TV that was watchable or even a landline back to the UK, so we were able to focus on our final match. We knew what we had to do – beat Poland to go through,” remembered an England squad member, one Gary Lineker. Aged 26 and top scorer in the First Division the previous season with a brilliant 40 goals for Everton, Lineker had developed a reputation as a great poacher and, leading up to this tournament, England’s most dependable striker. Could he be the one to deliver a miracle in the final group match against old on-the-pitch sparring partner Poland? The answer was emphatic.

Wearing a plaster-cast owing to a broken wrist, as well as the esteemed number 10 shirt, and thanks to his intuitive positional awareness and some decisive attacking football from his team, Lineker struck in the ninth minute, then the 14th, and then the 34th. A first-hat-trick. And an absolutely electric one at that. From being no-hopers that hadn’t mustered a single goal, England – with Lineker lethally leading the line – suddenly looked a dangerous foe for anyone in the second round.

Gratiously, this was the first World Cup in four in which the second round wasn’t a second group stage, but the beginning of the knock-out tournament proper – as it sensibly and entertainingly has been ever since. And joining England there were all the usual suspects. Holders Italy and the impressive looking Argentina qualified from the same group – Italy drawing two matches and winning one; Argentina winning one 2-0 (against Bulgaria) and another 3-1 (against South Korea, in which Italy-based star turn and captain Diego Maradonna grabbed a brace). Brazil made it through with three group victories (and packing stars from four years before Sócrates, Zico and Falcão), dismissing among others a Northern Ireland side sadly unable to match their achievements of ’82. France, who had been a fine side in the last World Cup and were scintillating winners of 1984’s European Championships, were surprisingly outshone in their group by a very attacking Soviet Union (who beat Hungary 6-0), yet they qualified for the next round in a comfortable second place. The two drew 1-1 against each other in a match memorable for a 40-yard screamer scored by the Soviet Vasyl Rats past the French keeper Joel Bats. Rats versus Bats? Yes, you couldn’t make it up.

This tournament – as so many seem to – also featured a ‘group of death’. Who did it contain? Why, West Germany, Denmark, Uruguay and Scotland, of course. Yes, I kid you not, in 1986 this was considered a groupe de mort. Mind you, it proved to be a stonker, not least because Denmark, not West Germany, progressed from it with a 100 percent record. The dynamic Danes beat Scotland 1-0, the Germans 2-0 and routed Uruguay 6-1. Impressive stuff and no mistake. For their part, the Scots gave it a go, what with spunky little midfielder Gordon Strachan opening the scoring against West Germany (the latter eventually winning 2-1), but not managing to win a game, it was they who went home early and the Germans who happily went through in second place behind Denmark.

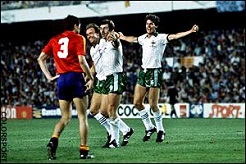

What the football gods had given the Danes in their first three matches, they took away in their fourth, however. Yup, they crashed out – and, believe it or not, to those perennial World Cup under-performers Spain, with Real Madrid star Emilio Butragueño grabbing four goals in a 5-1 win. Elsewhere, in an absolute cracker, Belgium shocked everyone by defeating the Soviet Union 4-3 after extra-time – Soviet striker Ihor Belanov scored a hat-trick, but conspired to end up on the losing side – while Brazil beat Poland 4-0; France knocked out Italy 2-0; Argentina defeated Uruguay 1-0; and the Three Lions roared again, marching past Paraguay 3-0, with Lineker getting another two goals and his front-line partner, Liverpool’s skillful Peter Beardsley, the other. For many, though, the highlight of the round was host Mexico’s 2-0 victory over Bulgaria, thanks to an unforgettable goal scored via a scissor-kick from Manuel Negrete Arias.

Spitting image: ITV’s fun football pundits Saint and Greavsie were in their prime during Mexico ’86 (left), just as was France ace – and present UEFA chief – Michel Platini (right)

For the most part, the next round, the quarter finals, weren’t the most exciting – certainly in terms of goals. Three of the four matches ended in draws and had to be settled by penalties. Germany versus Mexico finished scoreless, with the former winning the shoot-out; Spain equalized against Belgium on 85 minutes, but lost 5-4 on spot-kicks; while, in an admittedly entertaining match, the brilliant Zico missed an easy chance and had a penalty in normal-time saved, as his side drew 1-1 against France. The latter’s goal came from their talismanic captain Michel Platini, on his birthday, and he too missed a penalty, this time in the shoot-out. Yet, with another miss during the old 18-yard box lottery from Brazilian Sócrates, it was the French who finally did the business, by four penalties to three.

The fourth quarter final, however, was a match unlike the others. In fact, it was unlike any match in this World Cup – and unlike many matches in any World Cup. Indeed, it was the game that, come the end, this entire tournament seemed to revolve around. At the tender age I was then, I guess it was the first football match I ever actually watched – and, given it was England against Argentina, The Flintstones it was not.

Thanks to the notoriously ill-tempered match between the two in the ’66 World Cup, sporting bad-blood already existed between England and Argentina. However, the hostilities, casualties and result of the Falklands War lent this fixture another dynamite dimension. It was four years since the war and, of course, the English public had far from forgotten it, but as a country beginning to be bouyed by a resurgent economy driven by the City of London and as the victors of the aforementioned conflict, this footballing clash was more about extra spice than some sort of a re-match. For the Argentine public, however, anticipation for the game was different – it was more like awaiting an Olympic meeting contested by the USA or the USSR at the height of the Cold War. Indeed, following the match, Diego Maradonna commented: “Although we had said before the game that football had nothing to do with the Malvinas [Falklands] War, we knew they had killed a lot of Argentine boys there, killed them like little birds. And this was [about] revenge”.

Magic moment: Maradonna on his way to scoring his sensational second against England

The two teams went off at half-time even-steven – Argentina had had the better of it, but hadn’t managed to breach England’s defence. All was to change in the second-half, though. And on 51 minutes, the first of two utterly unforgettable moments occurred. Having started a move, Maradonna ran on deep into the England half, expecting a one-two from striker Jorge Valdano. The ball, however, came back to him from a skewed clearance from England midfielder Steve Hodge, looping up ahead of the diminutive player. England’s 6′ 1″ goalkeeper – and captain for the match – Peter Shilton rose to punch the ball clear, while the 5′ 5″ Maradonna jumped towards it too. Surely the latter’s jump was in vain? Apparently not. The ball bounced away from the two of them and into the England net. The referee, Tunisian Ali Bin Nasser, blew his whistle and awarded the goal. 1-0 to Argentina. But, suddenly, Shilton raced towards him, tapping his arm, flagrently indicating that his opponent had, in fact, handled the ball and that the goal shouldn’t stand. Quickly catching wind of what Shilton was saying, other England players began to crowd around the referee and claim the same. Yet, the referee – and his relevant linesman – hadn’t seen the infringement and so would hear nothing of it: the goal stood. Instant TV replays from a reverse angle backed up England’s cause – with bells on. Maradonna had deliberately – and cutely – fisted the ball a split-second before Shilton could reach it.

Four minutes later, though, the Argentina number 10 created another incredible moment – this time one of utter magic. Picking up the ball in his own half, he went on a 10-second, 60-metre run, beating four England players as he did, and finished it off by placing it past Shilton and putting his side two goals clear. In the years since, many observers have claimed this to be the ‘goal of the century’ or, plainly, the best ever scored. It may be. Such a thing is very difficult to quantify to my mind. What is undeniable, though, is that it was a piece of otherworldly skill – and, ironically and bittersweetly, in direct contrast to the moment that directly preceded it.

After two such extraordinary moments, one would be forgiven for thinking that Argentina were now out of sight, that England were dead and buried. Were they ever, though. Showing the smart and tactically-aware manager he was, Bobby Robson made a double substitution and brought on two exciting players in the shape of Chris Waddle and Liverpool superstar John Barnes. Sparked into life by this change, England gave it a real go and started to press and attack themselves – midfielder Glenn Hoddle soon went close with a free-kick. Then, in the 80th minute, John Barnes rampaged down the left and delivered an acute cross into the penalty area that Lineker deftly headed in – it was his sixth goal of the tournament. Another Barnes cross seven minutes later caused further panic for the Argentines when Lineker nearly reached it again, but this time it was not to be. And, in the end, so proved the match for England. They lost 2-1 – that late goal, though they were beaten, ensuring Maradonna’s moment of blatant cheating had proved critical; his brilliant goal would not alone have been enough to defeat them.

“Un poco con la cabeza de Maradona y otro poco con la mano de Dios” (“A little with the head of Maradona and a little with the hand of God”) ~ Diego Maradonna shares with the world how his cheating goal against England was scored, and so the ‘Hand of God’ reference is born

Immediately following the game, England defender Terry Butcher was required to give a urine example for routine drug-testing, along with Maradonna. Meeting the man during the process, he asked him whether he’d used his head or hand to score the first goal; the reply being the head. Butcher, an ardently competitive and patriotic sportsman, has since claimed that if Maradonna had admitted to him he’d cheated, he’s not sure what he would have done to him. And, somewhat less courageously, that’s exactly what the Argentine admitted to the world’s media minutes later – suggesting the ‘hand of God’ had been involved in the scoring of the goal. Bobby Robson knew his mind all right, though, claiming instead it was the ‘hand of a rascal’ what had scored it. Maradonna has also since admitted that immeditaly following the hand-ball he urged his teammates to hug him, otherwise the referee may not have allowed it.

All the same, there was no getting away from it, a decent England team – the first since the defending champions of 1970 – were out; the Argentines were through to the semi-finals. Less controversially, they beat Belgium 2-0 there (Maradonna scoring another outstanding goal in that match) and West Germany, the efficient, well-oiled machine of this era they were, beat the star-studded French 2-0 as well. And so to the final, and quite the exciting match it was too. Argentina took the lead after just nine minutes through defender José Brown, and Valdano added another in the 55th. However, the Germans had other ideas, what with veteran midfield powerhouse Karl-Heinz Rummenige scoring in the 74th minute and striker Rudi Völler grabbing an equalizer on 80 minutes. Yet just three minutes later, and thanks to a pass from the ubiquitous Maradonna, Jorge Burruchaga sealed the deal and got the winner. For the second time in their history then – in fact, the second time in three World Cups – Argentina were champions.

It’s little surprise that in the years since, this World Cup has generated much debate – all of it, seemingly, pivoting around that England-Argentina match and those two moments from Maradonna. To my mind, his performance in Mexico ’86 and, especially, his second goal in that game has ensured he must be considered one of the greatest footballers ever to have played the game (perhaps he’s even second only to Pelé himself). Yet, that’s only one side of the coin and can only ever be viewed as such. Maradonna had dark moments in his career both at international and club level following this World Cup, but just on its own his first goal in that match in question tempers all else he achieved in that tournament. All these years later, I’ve never been able to get away from the conclusion I came to as a six year-old at the time – for all his God-given talent, Diego the little devil was a plain and simple cheat.

Golden boy: England’s six-goal hero and new national treasure, the one and only Gary Lineker lifts a paper – if not World – cup following his hat-trick against Poland

Overall though, this World Cup probably wasn’t a bad ‘un, it’s only fair to say – not the classic of 1970 that Mexico also staged, but it was never going to match that one, surely? And it did offer a couple of silver linings too. Not only did Belgium pull off the incredible coup of finishing fourth (when are they next going to repeat that feat, honestly?), but England’s Lineker proved himself Gary the Great and the nation’s favourite son by finishing the tournament’s top scorer and thereby winning its Golden Boot – the first, and so far, only Englishman to have done so in a World Cup.

But after all my thoughts and words, what is the take on this World Cup by its winners? Well, you may be a little surprised, because according to former player Roberto Perfumo (whose international career ended in 1974): “In 1986, winning that game against England was enough. Winning the World Cup was secondary for us. Beating England was our real aim”. Things that occur in World Cups often make you think, but surely that opinion offers a huge chop of Argentine-beef food for thought…

Listen, my friends! ~ July

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and enjoy…

Click on the song titles to hear them

~~~

The Youngbloods ~ Get Together

Donovan ~ Barabajagal (Love Is Hot)

The Band ~ I Shall Be Released

Julie London ~ Light My Fire

Burt Bacharach ~ South American Getaway

Paul McCartney ~ Maybe I’m Amazed

The Rolling Stones* ~ Happy/ Let It Loose

Edgar Wright Group ~ Free Ride

War ~ Low Rider

Justin Hayward ~ Forever Autumn

Madonna ~ Borderline

David Bowie ~ Underground

~~~

* Yes, that’s right, a Stones double bill here from the legendary Exile On Main St. album – in honour of the recent documentary film on its making, Stones In Exile, no less. I know, I know, I spoil you, but you’re most welcome…

Blue steal: World Cup 1982 ~ Italy v Brazil

Assured azzurro?: Italy’s Paolo Rossi pursued by Brazil’s Sócrates in one of the all-time classic World Cup matches that would prove a critical turning point in 82’s terrific tournament

So, if you’re of an English persuasion like me, you’ll no doubt still be down in the mouth and in need of a tonic to get over the so-called Three Lions’ ignominious exit from South Africa at the weekend. And what better tonic could there be than to look back on this exceptional tournament and, in detail, its greatest match, in this, my fifth World Cup special? Well, short of throwing oneself into the smuggery of Wimbledon, I can’t think of a better one anyway.

Now, for some odd reason, the 1982 World Cup seems rather ignored or even forgotten when compared to its fellow illustrious football tournaments of times past. And that’s a shame, seems to me, because this one was an out-and-out crackerjack. Perhaps, over here in the UK at least, that has something to do with it taking place in the early ’80s. Before the rise of the yuppie, the invention of the brick-like mobile phone and Stock, Aitken and Waterman’s culpability for almost every song that found its way into the charts, the ’80s weren’t exactly a very colourful, optimistic or even an ‘us and them’ divisive time. Indeed, the early years of that decade were – perhaps predictably – far more like a continuation of the previous one and, thus, not too fondly recalled nowadays.

The fact was the policies – for better and worse – of new Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher hadn’t really bitten Britain yet and no single demographic of the population was clearly feeling the effect of 1979’s Tory election victory. In which case, money was tight for pretty much everyone as the economy was still far from bouyant, unemployment was high (although it would only rise in the next few years, of course), and civil unrest had reared its ugly head once more.

Famously, in April 1981, a day-and night-long violent riot had taken place in Brixton, a very multicultural borough of South London, thanks to the the area’s crime rate having grown rapidly owing to a recent rise in unemployment. The rioters, who were white as well as black, were initially angered by the sudden surge in police presence and its heavy-handed stop-and-search policy. Time Magazine referred to the event as ‘Bloody Saturday’, an allusion to the so-called ‘Bloody Sunday’ in Belfast at the height of ‘The Troubles’ in the early ’70s. Less well remembered is that in the same year similar riots had also broken out in Birmingham, Liverpool, Bristol, Leeds, Leicester, Coventry and Edinburgh, among other cities. Culturally, the feel of urban decay and despair seemed to be reflected through song with the ska-flavoured Ghost Town by The Specials and the driving punk-pop London Calling by The Clash, both of which were big chart hits of the era. The ’70s were over, but the country still seemed to lack direction then; it still felt like a sleeping giant that couldn’t quite pull itself up and forwards – and it desperately needed to.

Picasso and fiasco: World Cup ’82’s poster, inspired by the work of Spain’s greatest artist; tournament mascot Naranjito; and violence on the streets of London’s Brixton in 1981

In many ways, the same could be said for the England team that qualified for the World Cup of Summer ’82, held in Spain – although they were the first to do so in eight years. Indeed, the team even wore skin-tight shirts with bad patterns on them and very short shorts (or strangely iconic ’80s sportwear, if you prefer), just like every man on the street of Britain seemed to wear in early ’80s summers. And manager Ron Greenwood’s men hardly seemed like glamorous world-beaters either. Instead of 1966’s Charlton, Hurst, Moore and Banks, the class of ’82 boasted the likes of Francis, Wilkins, Brooking and an injury-carrying Kevin Keegan. Oh, and a promising young lad named Bryan Robson.

Ah, Bryan Robson. In actuality, it wasn’t the perma-permed Keegan, but this midfielder with energy and endeavour comparable to that of a Duracell bunny who turned out to be England’s talisman this tournament. And he hit the front as soon as 27 seconds into the side’s campaign, putting them 1-0 up against the much fancied France (packing the terrific Michel Platini and others) in their opening game. Impressively, this goal was to rank the fastest in World Cup history for the next 20 years. And come the 67th minute, Robson grabbed another – undeniably, a new star was born on the international stage – and thanks to a late strike from Paul Mariner, England won 3-1 and were off to a great start.

Indeed, with a further 2-0 win over Czechoslovakia and 1-0 win over Kuwait, in both of which striker Trevor Francis scored, England cruised through to the second group stage with a rare 100 percent record. Unlikely it may have seemed, but they were doing all right, better than all right, actually. Could they, as promised in their official tournament song, really ‘get it right this time’? Of seemingly less interest at this stage, France also made it through the group in second place.

Actually, as if to kick some juice into the ’80s, right from the off and all over the shop this was an exciting World Cup. The tournament had, in fact, opened with an Argentina-Belgium fixture – surely a bog-standard victory for the former, the reigning champions? Erm, well, no as it turned out. Having underestimated their rivals, the Argentines fell to an embarassing 1-0 defeat. Still, along with the Belgians they did manage to progress to the next round. Almost as impressively, the other highlight of this group was the match between its two minnows, Hungary and El Salvador, which was won to the tune of 10-1 by the former, surely reminding their nation of the fine side it possessed back in the ’50s. This crazy scoreline is still the joint second highest ever achieved in the competition’s history.

Burly start, curly non-stalwart: Bryan Robson scores his first goal against France; Kevin Keegan struggles and, inset, the fashion statement that was the World Cup ’82 England shirt

Elsewhere, the mighty West Germany’s opener produced another unexpected result, beaten, as they were, 2-1 by Algeria – the first ever African victory in a World Cup. Erstwhile and efficient as ever, mind, the Germans did make it through to the next stage, but not without controversy. In their final game of the round, they faced Austria (with whom they’d shared an infamous match in the ’74 contest) and the two teams, knowing they’d both go through if West Germany won 1-0, completely shut up shop and kicked the ball around in a strange unspoken agreement as soon as the former scored a goal early in the first half. The Spanish-majority crowd, TV audiences around the world and even the fans of the two countries were appalled by this behaviour – disgusted, a German fan in the stadium even burned his nation’s flag. How could this have happened?

Well, just as in the immediately previous World Cup when Argentina had managed to get through to the final with a dubious defeat of Peru, this match had taken place after all the others in the group had been played so both teams knew exactly what they needed to do in the game. This sort of thing needed stamping out once and for all, and finally in the next tournament FIFA ensured such an unfair advantage wouldn’t take place again, but clearly the desire to act had come not one, but two, World Cups too late.

There were three more groups in the first round this year (yes, that’s six in all) and, in spite of the three mentioned so far, none of them generated more surprise than the one in which Italy found itself. At the beginning of this tournament, it wasn’t so much Forza Italia as For goodness sake, Italia. In an occurence that, incredibly, would be repeated 24 years later in 2006, going into the contest the Italian domestic game had been rocked to its very roots by a huge match-fixing scandal across its top league Serie A. So bad had the debacle been that the clubs AC Milan and Lazio had been relegated to Serie B in punishment, while major players had served suspensions, including star striker Paolo Rossi who had been dished out with a two-season ban (even though evidence that’s since come to light suggests he may have been innocent).

All the same, to all intents and purposes the 1980 Totonero had surely provided the Azzurri with the worst possible preparation for this World Cup, and that appeared to be proved so in their opening group when, shamefully as far as their compatriots were concerned, they scraped through to the second round by the skin of their teeth, drawing 0-0 with Poland, 1-1 with Peru and 1-1 with Cameroon. In fact, the Africans were only denied the place that went to the Italians because they had scored one goal less, tied on points as they were. This was despite the fact the former had had a perfectly good goal from striker Roger Milla disallowed against Peru. In great contrast to Italy, Poland put five past Peru and qualified for the next round by topping the table. Indeed, the Poles were bolstered by the now legendary striker-from-midfield Grzegorz Lato appearing in his third consecutive World Cup – unsurprisingly, he was one of those who’d got on the scoresheet against the Peruvians. Rossi, meanwhile, hadn’t come close to a sniff in his three matches and, famously, the Italian media is supposed to have referred to him as a ghost wandering aimlessly over the field.

The pluck of the Irish: Northern Ireland defeat Spain (left) thanks to a strike from hero Gerry Armstrong (right)

Wandering aimlessly through the first group stage had been the preserve of the home nations in recent World Cups, but, like England, another UK representative had a cracking time of it – frankly, to the utter shock of the footballing world and, in particular, the hosts. Northern Ireland had qualified for the ’82 tournament – their first in 32 years – and following plucky draws against Yugoslavia (0-0) and Honduras (1-1), they did the unthinkable, yes, thanks to a single goal they beat Spain… in Spain… in Spain’s World Cup. An amazing feat that saw them through to the next round by incredibly topping the group. The Spanish, a disappointing team in their home World Cup, joined them there with a record of one win, one draw and that one loss against the Northern Irish.

If luck was going the home nations’ way elsewhere, then, perhaps predictably, it didn’t rub off on the Scots. Through to their third Cup in a row, they – like everybody else in their group – demolished New Zealand and claimed a fighting draw against the Soviet Union, but that result wasn’t good enough and saw them cruelly go out – yet again – on goal difference. However, in truth, this group was only really about one team. Indeed, the entire early stages of the tournament were only really about one team… Brazil. Yes, that’s right, Esquadrão de Ouro were back, and, indeed, they did appear to be a golden squad once more.

For they had captain, midfield maestro and eventual cult figure Sócrates, who was as much loved for his terrific beard as for his silky skills (and for sharing his name with Ancient Greece’s pre-eminent philosopher, of course); they had the goalscoring machine that was Zico (also, in fact, a midfielder rather than a striker – well, he was Brazilian, after all); they had another outstanding midfielder in the shape of the marvellous Falcão; they had the left-winger with a beautiful touch Éder; and, finally, they had the very useful striker Serginho. Just like back in 1970 when they’d last won the thing, the Brazilians looked the real deal, displaying footballing ability and clinical finishing unlike any other side thus far. They defeated the decent Soviets 2-1, beat up Scotland 4-1 and put another four past New Zealand without reply; Zico scoring three, Serginho two, Éder another two and Falcão yet another two in the process. To say by the end of the opening group stage they were favourites for the tournament would be like saying cameramen traditionally like lingering on on bikini-clad Brazilian female fans dancing in the stands. World Cup ’82 was well and truly rocking already, and to an undeniable samba beat.

Puzzlingly, unlike in the last two World Cups where the second group stage had comprised two groups of four teams, this one’s second round of groups comprised four of three teams. Three may be a magic number, but it’s an odd number for a group in a football contest, surely. However, this change did ensure that the winners of each of the new groups – four of them, of course – would go through to a pair of semi-finals, which had been blessedly reinstated after going AWOL in the ’74 and ’78 tournaments, so perhaps there was some actual method to the madness. Talking of methods, having applied a successful one to their first group, the Poles did exactly the same to their new one (the first of the second round), beating Belgium 3-0 as they did, thanks to a hat-trick from hot-to-trot striker Zbigniew Boniek, and drawing against the Soviet Union. After their previous heroics, Belgium, a little sadly, weren’t to go any further; conversely, Poland were the first side through to the semis.

And joining them there – you guessed it – were West Germany. The nation who, by now, was really making a habit of being there or thereabouts in every football contest in which it participated, got the better of both the pretty woeful Spain and, yes, England. The Germans beat Spain 2-1 and drew 0-0 with England (hardly a match that latter one, then, to rival the clashes of ’66 and ’70). For their part, England also picked up another 0-0 draw with the hosts. In the end, injuries – in particular to the man who perhaps could have delivered the goods for them, the Superstars superstar himself Kevin Keegan – had caught up with the English this campaign, but they did have the (in)glorious honour of returning home having not lost a game.

In contrast, the side who England had so impressively beaten in their first match, France, cruised through their second group, beating Austria 1-0 and Northern Ireland 4-1. This second stage was clearly a step too far for the otherwise terrific Northern Irish, but they’d had a legendary tournament and could boast one of its top scorers in three-goal hero Gerry Armstrong, who – given his team had defeated the hosts – would somewhat ironically switch Watford for Real Mallorca the following year. As Jimmy Greaves had a wont to say once upon a time, football really is a funny old game.

The final group of this World Cup was unquestionably what the media would nowadays dub ‘the group of death’, containing, as it did, Brazil, Italy and Argentina. The latter of those three were, of course, the World Cup holders, but losing as they already had to Belgium, they weren’t the team of four years before (not least because they didn’t possess the huge home support they had enjoyed in their home country then). They fell first to a 2-1 defeat to Italy – the latter’s goals coming from decent-looking midfielder Marco Tardelli and left-back Antonio Cabrini – and then to a 3-1 defeat to Brazil – for whom Zico and Serginho again scored. Those results ensured that the Argentines were out of it and it now all came down to the Brazil-Italy clash to decide the final semi-finalist. And what a clash it turned out to be. In a word, it was incredible.

Dream team: Brazil’s Falcão, Zico and Serginho in action – but could they win the World Cup?

Not that, before kick-off, it looked like it was going to be that much of a contest, of course – Brazil were the undoubted pre-match favourites. Yet, lest we forget, in addition to its importance as a decider of a semi-final place, this match also saw these two great footballing nations clash for the first time in a meaningful World Cup tie since the classic 1970 final. And, just as then, it was those in green and gold who held all the artistic aces, beginning the game, as they did, with the sort of skill, style and flambouyance they’d shown throughout this tournament. In answer to this, the Italians looked set to rely on an old favourite of theirs, catenaccio – the smart, if not arty, tactic of playing defensively (indeed, catenaccio translates from the Italian as ‘door-bolt’) – a method of play dreamt up and used very effectively by Inter Milan in the ’60s to scoop up Scudetto after Scudetto. In actual fact though, the system Italy used in this World Cup was a slightly modernised, more flexible version that has become known as zona mista (‘mixed zone’) – and, make no mistake, the boys in blue used it in this match with bells on.

The first indication that the game wasn’t going to go to the script – or even go to the form of either side so far – was unmistakeable: Paolo Rossi scored a goal. The event took place just five minutes into play too, when the much-maligned marksman nodded in a cross from Cabrini, showing the true poaching instincts that had made him such a star in his homeland years before and which had so far eluded him so clearly this competition. True to their instincts as a good Brazilian side though, the samba boys didn’t panic and played their natural easy-on-the-eye and, when necessary, powerful and decisive football – and got what they deserved in the 17th minute when a marvellous move culminated in Sócrates brilliantly striking home at the Italian keeper’s near post. 1-1. This was shaping up to be a good contest. And it got better.

Just three minutes later, stepping past a defender and intercepting a loose pass across the other penalty area, an utterly reinvigorated Rossi lashed home a shot into the Brazilian net, putting his side back into the lead. 2-1. If the Brazilians were stunned by going behind again – and to Rossi again – they didn’t show it. Instead, they bombarded their opponents’ half of the pitch and bore down on the opposing penalty area for much of the remainder of the match. However, owing to the Italians’ drilled organisation and, in particular, the exceptional work of central defenders Claudio Gentile and Gaetino Scirea, the South Americans just couldn’t get through. The passes, interplay, shots, strikes, volleys and venom from the Brazilians were no good, the Azzurri were standing firm – and conducting an admirable masterclass in how perfectly to counteract such great forward play. Indeed, Gentile had been charged the unenviable task of man-marking Zico and so good did he do it he picked up a yellow card for his efforts, but Brazil’s irresistible Number 10 neither scored a goal nor set up another the entire match.

Finally, however, the fabulous Falcão did find a way through the Italian resistance when he scored from a full 20 yards out in the 68th minute, the delight and relief etched on his face as he celebrated with his teammates – at 2-2, Brazil would now be through to the last four on goal difference; the Italians out. But someone had other ideas. And who was it? That’s right, you guessed it. Popping up in the Brazilian box just six minutes later and connecting as quick as lightning to a poor clearance from his side’s corner, that man Rossi sealed an amazing hat-trick, sending his team 3-2 in front and, yes, into the semi-finals.

Keeper’s KO: Harald Schumacher crashes into Patrick Battiston in the second semi-final

Over the years, many have decried this match owing to it sending such a brilliant Brazilian side out of the World Cup. Indeed, the BBC’s John Motson has claimed his co-commentator for the game Bobby Charlton cried at the end of it for that very reason. Yet, there’s always two sides in a football match, and there’s often two ways of playing one – and this match showed up both in their equally fascinating extremes. While Brazil played near-fantasy football in this World Cup, the style the Italians played was (arguably) just as impressive, more effective and ultimately smarter. Their defensive counter-moves to Brazil’s forward-efforts were brilliant in their own way and their break-away counter-attacking (now such a recognisable and welcome part of modern football the world over) was thrilling, decisive and winning. There’s a reason why it took Brazil 24 years to win their next World Cup after the beautiful triumph of 1970; until 1994 they didn’t play defensively – or, if you like, smartly – enough to do so. It was perhaps this very match that taught them the lesson that free-flowing, fluid, forward-dominated football wasn’t enough to conquer the world anymore; you needed to be smart like the Italians too.

And lucky as well, it should be said. For in their semi-final the latter met the Poles, who, having had a great tournament thus far, really didn’t perform and against an Italy that had just found its form – fortuitously? – at the right time went down 2-0. Both goals came from Rossi. Italy too were perhaps lucky they didn’t face either side that contested the other semi-final, two true European powerhouses in the sport at this time, France and West Germany. And, make no mistake, this particular meeting made for another stonker of a match.

The drama began as early as the 17th minute when German midfielder Pierre Littbarski opened the scoring, only for his goal to be negated by a Michel Platini penalty in the 26th. Platini was involved again in the second half’s – and probably the entire match’s – most memorable moment when his fine pass put defender Patrick Battiston through on goal, only for German keeper Harald Schumacher to come racing out and… not clear the ball, but miss it completely as he delibarately floored the unrushing Frenchman. Play was halted for several minutes while the unconscious Battiston was stretchered off the pitch, the result of which being that neither a penalty was awarded nor was Schumacher sent off, the referee deeming the assault not even to have been a foul. For his sins, the coolly gum-chewing, shockingly permed German keeper took the goal-kick and the game resumed. At least after the match he offered to pay Battiston’s dental bill when it was revealed he’d knocked two of the poor feller’s teeth out, although one may say that was adding insult to literal injury.

Into extra-time the match went then and on 92 minutes, French sweeper Marius Trésor volleyed home to make it 2-1 and six minutes later his teammate Alain Giresse finished a swift counter-attack to put their side two goals clear. But you can never count out the Germans, oh but you can’t. On 102 minutes they themselves scored following a counter-attack through Bayern Munich’s European Footballer of the Year, German squad captain and very recent substitute Karl-Heinz Rumenigge, while in the 108th a terrific move was topped off by a volley into the net in the form of a bicycle kick from Klaus Fischer (since voted German football’s greatest ever goal). The scores were level once more then at 3-3, and that meant… penalties. Of course, penalty shoot-outs to decide knock-out matches in international football are ten-a-penny nowadays, but back in 1982 they were a great rarity. Thus, this fatalistic, sado-masochistic manner to decide a winner merely seemed to lend this epic match a fittingly über-dramatic climax. And, predictably, it was the Germans who proved the über penalty-takers, winning the shootout as they did – as they always seem to.

Abiding memories: Paolo Rossi scores – again – in the final (left); Marco Tardelli’s explosive and utterly unforgettable goal celebration (right)

So, Italy versus West Germany in the final. It had a nice ring to it and, as if this World Cup hadn’t had enough already, it proved to be yet another memorable, quality match. Save a missed penalty from Italian Cabrini, the game was goalless and honours even going into the second half – and that’s when it really sparked into life. And who was it who provided the spark? Who else could it be now but Paolo Rossi, as in the 57th minute he headed in a low cross at very close range. Having mastered their zona mistra system against the Brazilians, the Azzurri now struck gold with it against the Germans. The latter were clearly knackered from their huge semi-final exploits against the French, while their far sprightlier opponents wre defending superbly (especially Gentile and Scirea again), which ensured they could counter-attack and apply the sucker-punch – not once, but twice. First, on 69 minutes Tardelli scored from range to put Italy two clear, then substitute striker Alessandro Altobelli sealed the win twelve minutes later following a great solo run from Conti down the wing. Paul Breitner managed to pull one back in the 83rd minute for the Germans (impressively, his second goal in two World Cup finals, as he’d already scored a penalty in the ’74 final), but it was scant consolation. The boys in blue had done it – they’d won the World Cup for the third time in their history.

And, following the terrible match-fixing scandal that had preceded their tournament and the frankly terrible start they’d made to it, it was rather a remarkable win for them too (indeed, as hinted at earlier, the whole thing seemed to repeat itself for Italy as they went into, competed in and eventually won the 2006 World Cup – bizarre really). Not just that, though. Having been a laughing stock right up until his side’s third match from the end, Rossi finished the contest as top scorer with six goals, ensuring he picked up not just the Golden Boot, but also the newly introduced Golden Ball award for the tournament’s best overall player. Not bad going for an aimless ghost.

Perhaps this terrific tournament’s most enduring memory, though, is the celebration of Marco Tardelli as he scored Italy’s second – and decisive – goal in the final. Raising his hands in clenched fists, his mouth opening into a square and his eyes widening, he sprinted away along the pitch and towards his team’s bench, completely lost in the ectasy and majesty of the moment. And, you’ve got to say, it’s an image that fits this tournament like a glove, one of the most entertaining, exciting, colourful, controversial, crazy and unpredictable sporting contests there’s ever been. Yes, it was 1982 and it may have been drab in Britain, but this World Cup and all its components had surely afforded the country – and the world – something of a taster of the extraodinary decade that was to come…

Soul survivors: Mick and Keith during the making of Exile On Main St. – for once the two seem without booze, maybe that’s why Mick’s face suggests Keith’s playing a bum note

Whichever way you wrap it, 1972’s Exile On Main St. has always been the oddest of their great gifts The Rolling Stones have bestowed on us over the decades. A double album that was crafted during the period the band should surely have slowed down following their spiritual leader Brian Jones’ death in 1969, it’s also stripped back, bluesy and hopelessly loose – just when you’d have thought they’d have retreated into the safe embrace of studio technology and trickery, instead of taking the seemingly harder and more dangerous route of going back-to-basics. Plus, for all its (rightfully) accumulated acclaim over the years, the album only contains one tune that turned out to be a genuine hit single.

Yes, it’s always been a bit of a curate’s egg – if one of which exquisite trinket maker Carl Fabergé would have been proud. So, good news it is then that the brand spanking new 61-minute documentary that looks at the album’s making, Stones In Exile, goes a damned good way to explaining why.

As if in keeping with the undiluted, rather shambolic genesis and ethos behind the album in question, this docu film, directed by Stephen Kijak, was both premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and shown on BBC1 in the UK last month, at almost exactly the same time. A bit weird to my mind that, I must say. Still, it did mean I didn’t have to worry about having to rub shoulders with the movers and shakers on the Promenade in the vain hope I may get hold of a ticket from a tout – no, instead I could watch the whole thing at home in the comfort of my favourite armchair and with a nice cup of coffee. Who could ask for more? Well, going to Cannes would have been cool, I guess.

Exile On Main St.‘s origins were not promising; in fact, they were downright ominous. Owing to businessman Allen Klein (who was famously involved in screwing up The Beatles’ finances, which helped bring about their demise) sticking his finger into The Stones’ money matters towards the end of the ’60s, following the legendary Andrew Loog Oldham’s departure as their manager, the band were facing financial – as well as legal – problems. And problems that for a rock ‘n’ roll band, which at the time was undisputedly living the archetypal rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle, were seemingly too complex and difficult to get their heads around.

Let It Loose: As he says in the film, Keith proves he was more ‘roll’ and Mick more ‘rock’ during the recording of Exile On Main St. – but a hell of a smack was about to hit him

Basically, it boiled down to the fact that the four main members of The Stones hadn’t paid tax for several years and were required to clear their debts with the Inland Revenue as quickly as possible. However, there was another problem. Britain’s finances too were in a mess at this time and UK residents at the highest end of the wage earning scale, as The Stones were now, were required to pay as much as 97 percent in the pound (£) to the taxman. In short, living and working in Blighty, the band actually couldn’t make enough money quickly enough to pay the state back what they owed. There was one solution, therefore – leave the country and set up home elsewhere. As it happened, guitarist Keith Richards and his German actress wife Anita Pallenberg, fresh with a toddler daughter, had just started renting out a sixteen-room mansion called Nellcôte on the seafront of Villefranche-sur-Mer, not from Nice on the French Riviera. France it was for The Stones then.

However, perhaps surprisingly for peeps who had become well accustomed to jet-setting here, there and everywhere by now, leaving Britain behind was a bind for the band. And covered nicely in the film is this point, for while drummer Charlie Watts mentions that moving country naturally meant there was a language barrier to tackle, guitarist Bill Wyman recalls he had to have all his favourite British food sent over – you could get hold of PG Tips that way, all right, but you still had to contend with French milk. The band quickly decided their next money-making venture would be an album and, without any studios to meet their requirements in the south of France, they opted for the next best thing. Oddly, this turned out to be attempting to record the thing at Richards’ villa. It was probably one of those ideas that sounded brilliant at the time. Over a bottle of Jack Daniels. The trouble was they quickly discovered that it would be completely impractical to play and record in the house’s large ballroom, as they had planned. This ensured that recording would have to take place throughout the dank and dirty cubby hole-like rooms that made up the mansion’s basement. To say this arrangement wasn’t ideal would be a gross understatement.

Using a mixture of anecdotes from those involved, archive filmed footage, music from the album and photography captured by a snapper who had turned up at the villa before everyone else merely to get a few shots of Richards and Pallenberg, but instead stayed the entire summer, the documentary does a fine job of getting across the totally disorganised, haphazard and frankly nuts recording work that went on at Nellcôte. In truth, it was like one long jam-session that went on alongside a months-long party. As frontman Mick Jagger admits, they could get away with doing it because they were young – surely no music artist over the age of 30 and in their right mind would consider recording an album that way. Indeed, it’s unlikely any music artist would be able to get away with recording an album that way nowadays at all. Still, somehow – and despite all the distractions – The Stones magically pulled it off. And, boy, were there distractions too.

Booze, drugs, wives, kids and numerous hangers-on (besides saxophonist Billy Keys and manager Jimmy Miller) were everywhere. The film effectively suggests the album was almost secondary to the party. Yet – and for me this is sadly where Stones In Exile pulls its punches somewhat – it doesn’t really get into the nitty-gritty of what really went on. Yes, we learn that only some musicians were around some of the time, and when there they’d jam and play day or night (whenever they were awake, often); and that the music from the basement was so loud that it could be heard from the beach, but curiously none of the neighbours complained; and that everyone would eat together for lunch prepared by cook ‘Fat Jacques’; but the more juicy, controversial stuff, which clearly went on, is rather glossed over. The closest we really get to it is being told that the band members’ kids pretty much fulfilled the roles of joint-rollers and that everybody was on ‘Keith’s time’ – an allusion to his and Pallenberg’s descent into heroin addiction during this summer.

“‘Happy’ was something I did because I was for one time early for a session. There was Bobby Keys and Jimmy Miller. We had nothing to do and had suddenly picked up the guitar and played this riff. So we cut it and it’s the record, it’s the same. We cut the original track with a baritone sax, a guitar and Jimmy Miller on drums. And the rest of it is built up over that track. It was just an afternoon jam that everybody said, ‘Wow, yeah, work on it'”. ~ Keith Richards on the recording of the Stones standard Happy, which to this day he himself sings on stage while on tour

One could certainly argue that had the film aimed to be more revelatory then it would have unlikely had the full involvement it does from The Stones – why would verteran rockers like them want to reveal what really went on back then? It’s certainly water on the bridge between them all now. Yet, knowing – if you’ve read around the album’s making – as you would, that Richards may well have moved on to heroin in reaction to Jagger sleeping with his wife while the two of them made the 1971 film Performance together, you may feel a little short-changed not to get more on the obvious antagonism and genuine strains the relationship between the band’s two leaders must have been under at this time. Not to mention the strains that must’ve been showing between the other members too.

Despite this, the documentary certainly continues to deliver nuggets. For instance, Jagger wrote the album’s hit Tumbling Dice after a conversation with a maid about how to throw dice when gambling. And, when the album’s second half of recording had upped and shifted to LA’s Sunset Sound Recordings studio (as was the norm for Stones albums of this period), following the time at Nellcôte exhausting itself in more ways than one, Mick remarks that he and Keith came up with the lyrics for Casino Boogie by writing phrases on pieces of paper, mixing them all up and pulling them out at random. By then, with difficult tracks as well as easier ones, it was just a matter of getthing them finished and recorded.

Stones In Exile, then, while providing a window – if not a microscope – on to what was going on in the fascinating lives of The Rolling Stones as they made this seminal album, finds its focus in examining exactly how the album itself was made. It was conjured up out of nothing, as good art often is, of course, but with the odds truly stacked against it; and yet, in their characteristic shipshod manner (and then some, in this particular case), Mick, Keith and co. somehow managed to unearth a diamond that to this day may just glimmer brighter than all their other albums.

Funny really then, that – as the film backs up – Mick still seems somewhat non-plussed with it, as if he wonders what all the fuss is about. Mind you, the most driven of The Stones (and its eventual leader), he was always about jumping into the next thing as soon as the last was over. Perhaps that’s why he is such a Soul Survivor – as usual, answers on a postcard as to how exactly Keith is, of course.

You can buy Stones In Exile on DVD here; or if you’re in the UK – and, no doubt, for a short time only – you can watch it on the BBC iPlayer here

Super Mario bother: Argentina main man Mario Kempes scores in the ’78 final against Holland, memorably played on a ticker-tape littered pitch – but darkness lurks elsewhere in Buenos Aires

All right, a word of warning before this, my fourth World Cup special, properly kicks-off. If you’ve been enjoying these ramblings from me about fantastic football tournaments past – I know someone out there must have been, surely? – then you may feel short-changed by this one. Yes, the fourth in this series of articles isn’t as celebratory in tone as the others so far. Why? Well, because the 1978 tournament wasn’t exactly one you’d call a classic. In fact, you might even say it was the nadir, the dark moment, certainly the black sheep among the modern-age Cups (and not only because it was the first to feature Coca-Cola as a sponsor). Still, as a culmination to the tale of ‘Total Football’ and being, as it was, the third and final episode in the trilogy of 1970s World Cups, it plays a role that, like it or not, can’t be ignored.

However, at the time, many English people may have preferred to have ignored it. For all the trials and tribulations going on in the UK at the time (strikes by dustmen and gravediggers; PM Jim Callaghan going to the IMF for a loan to bolster the ecomony; and the so-called ‘Winter of Discontent’ that would follow at the end of the year), there was a damn good reason why few looked forward to this World Cup. Yup, for the second time in a row, England had failed to reach the finals themselves – quite some disappointment, especially given both Liverpool and Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest were dominant in the European Cup around this time. Unlike four years before though, what with a poor qualifying campaign and the falling at the final hurdle thanks to the Wembley draw against Poland, this time the English could probably count themselves unlucky. They had played six games in their qualifying campaign, won five of them and lost only one against Italy. They had won the return home match against the Italians, but the latter had the exact same record and boasted a better goal difference – they were through; England weren’t.

Dot matrix and street wastage: the fun World Cup ’78 poster, logo and mascot, Gauchito; the ‘Winter of Disconent’, with rubbish seen everywhere – a bit like watching England then

Still, those of a more tartan persuasion had reason to be positive. Just like in ’74, Scotland had succeeded where England could not and were there in Argentina to represent the home nations (actually, thanks to a very controversial penalty awarded against Wales that saw them qualify instead of the latter). And, on paper, they had quite a decent looking team too, featuring the likes of Kenny Dalglish and Graeme Souness of Liverpool, Joe Jordan of Leeds United and Archie Gemmill of Nottingham Forest. Their manager Ally MacLeod wasn’t shy of talking up his side’s chances either, declaring before they flew out that they were so good they would return ‘at least with a medal’. His optimism proved mis-placed, though; in fact, Scotland’s overall performance made his pre-tournament confidence and bluster look rather ridiculous.

They opened their ’78 account by scoring first against Peru, but by the end had conspired to lose 3-1, and they then could only manage a 1-1 draw against Iran (their own goal being an, er, own-goal). Then one of their players, Willie Johnston, was embarassingly sent home for taking a banned stimulant. The third match seemed to promise little then, given it was against the ’74 runners-up Holland. Surely it would be an exercise of damage limitation? However, the Dutch – without the talismanic Cruyff, but otherwise blessed with sheer quality – had started the tournament sluggishly this time and, pulling themselves together, the Scots managed to neutralise striker Rob Resenbrink’s 34th minute penalty when Dalglish grabbed an equaliser ten minutes later. What happened next – just two minutes later, in fact – has gone down not just in the folklore of Scottish football, but also in the folkore of the entire country itself.

As Scotland pressed forward again, Gemmill latched on to a free-ball on the right and jinking past two Dutch players and playing a one-two with Dalglish, then deftly dinked the Dutch keeper Jan Jongbloed to put his side 2-1 up with a sensational goal. To this day, it remains one of the greatest goals scored in a World Cup and arguably one of the competition’s all-time golden moments (and plays a pivotal role in the iconic 1996 Britflick Trainspotting). Gemmill then tucked away a penalty to stretch the lead, but his next major moment wasn’t so clever – on 71 minutes Johnny Rep struck in the Scottish penalty area and, thanks to it deflecting off Germmill’s outstretched leg, the ball flew past goalkeeper Alan Rough. What the football gods gaveth Gemmill then, they tooketh away – as so often sadly seems to have been the case with Scotland down through the decades. This, the match’s final goal, pretty much ensured that this rare Scottish victory over the Dutch would be a pyrrhic win – on goal difference, again, they failed to make it through to the second group stage.

“I haven’t felt that good since Archie Gemmill scored against Holland in 1978!”: For Renton – and many Scots – Archie’s golden moment is even better than Trainspotting

Unlike the Scots, Peru – who started their tournament so brightly against the former – went through from their group and, impressively, ahead of the Dutch. Elsewhere, Austria shocked everyone by qualifying from their group ahead of Brazil. Poland, so good in ’74 and still packing Grzegorz Lato up front, managed to top their group ahead of holders West Germany, and Italy went through along with hosts Argentina, whom surely owed a real debt to their fanatical fans’ electric support in every match they played.

On to the second round groups then and, amazingly, Austria went one better than they already had – yes, they somehow defeated their big-time neighbours West Germany 3-2, the hero being forward Hans Krankl whose efforts and those of his teammates are still today lauded as Austrian football’s greatest ever achievement. Indeed, this match, in some ways an echo of the West Germans’ group stage defeat to East Germany in the previous World Cup, dented the Germans’ hopes of making the final, and draws against Italy and Holland (the latter an entertaining, if haphazard, replay of the previous tournament’s final) saw to it their title defence was over.

Conversely, it was in this same group that the Dutch discovered their form and, thanks to a 5-1 demolition of Austria and a 2-1 defeat of Italy, they topped the group. Indeed, although they weren’t exactly playing the brilliantly fluid ‘Total Football’ system they did in ’74 – and were missing Cruyff owing to kidnap threats against him and his family (his absence only being honestly explained in recent years) – they looked the real deal once again, playing fine football and scoring memorable goals. And now, once again, they were through to the World Cup final. What an opportunity, indeed.

The other second round group was, ultimately, struck by controversy; proper controversy. And in a very South American World Cup it involved the group’s three South American sides. Two of them, Brazil and Argentina, dominated proceedings, having both despatched Poland and rather disappointingly drawn 0-0 against each other. The table topper, of course, would go through to the final, so it came down to who could beat Peru by the most number of goals. Where was the controversy here then? Well, if one of the two sides kicked-off their final match – against the Peruvians – after the other’s final match, then they’d know how many goals they’d need to score to go through on goal difference, wouldn’t they? And that’s exactly what happened. And, suspiciously, it happened in favour of the hosts, Argentina – Brazil beat Peru 3-0; their rivals put six past them without reply. The Argentines were therefore through. That wasn’t all that was dodgy, though, given that it emerged the six-time-beaten Peruvian goalkeeper in that match, Ramón Quiroga, had in fact been born in Argentina. Both teams denied collusion in this regard and the tournament’s organisers couldn’t exactly be held culpable for ‘rigging’ Argentina’s progress to the final thanks to their matches’ scheduling, but the coincidences were, nonetheless, undeniable.

And that fact was disappointing because Argentina had a very good side. Coached by the chain-smoking César Luis Menotti (known as El Flaco – ‘The Slim One’) and driven by the centre-back who loved to attack, captain Daniel Passarella (who would go on to manage his nation in the 1998 World Cup), it also featured cultured, diminutive midfielder Osvaldo Ardilles and lanky play-maker Ricky Villa (who would both join English club Tottenham Hotspur the following season) and was spearheaded by moustachioed frontman Leopoldo Luque and major goal threat Mario Kempes. Yes, they were stylish, exciting and easy on the eye – even if, inexplicably, their squad was numbered alphabetically. Yet, as if willed on by the unfair advantage they’d received in match scheduling thanks to their compatriots who organised the whole shebang, they also didn’t mind playing dirty. And, frankly, that mired what should been a fine final.

It all started with the hosts keeping the Dutch waiting ready to start proceedings in Buenos Aires’ Estadio Monumental for five minutes, until they finally emerged from the tunnel to a gigantic tumult from the home fans packing the rafters. And that wasn’t all. In a concerted – and surely pre-arranged – effort, the Argentine players then complained to the referee about Dutch midfielder René van de Kerkhof wearing a plaster cast, even though he’d worn the cast on his wrist without previous complaint since his side’s opening match. Further minutes were wasted over the issue; indeed, the Dutch were so cheesed off they looked like they were about to walk off at one point. Eventually, the game kicked-off and in spite of the unsporting behaviour designed to rattle and unsettle the Dutch, the Argentines appeared to have gained no advantage as a balanced first-half proceeded, complete with a great deal of fouling and rule-breaking – mostly from Argentina – which scandalously, perhaps owing to the overpowering presence of fans with blue and white striped flags, went unpunished.

Winning ugly, losing fair: General Jorge Videla hands winning captain Daniel Passarella the World Cup; Dick Nanninga consoles a teammate after Holland come so close – again

Then, in the 37th minute, the deadlock was broken, as the long-haired Kempes expertly struck, putting his side in front. Unsurprisingly, the crowd went beserk, yet the men in orange didn’t wilt and – the second-half following much the same the pattern as the first – just eight minutes from time, conjured up a nice move topped off with Dick Nanninga heading in an equaliser. 1-1. Extra-time. Having led for some time and seeing victory snatched out of their hands so near the end, it wouldn’t have been surprising had Argentina deflated and run out of juice. Yet, they didn’t. Come the end of the first period of extra-time, up popped that man Kempes again and he just got enough on the ball in the penalty area to see it home and put his nation back in front. It was his sixth goal, giving him the Golden Boot and surely ensuring he was the player of the tournament too. Exhausted after a hard, physical match, the Dutch had gone for good now and, five minutes from the very end, right-winger Daniel Bertoni scored (despite a very strong suggestion of hand-ball), wrapping up the result and sparking delirious celebrations.

For the second World Cup in a row then, the Dutch had fallen at the final hurdle. Would they have managed to win the thing had Cruyff been in the side? Who knows, one can only speculate. Losing twice in a row in the final is a very painful reality, yet with the commendable magic and wonder of ‘Total Football’ which was so much the story of these two tournaments for Holland, theirs are nowadays looked upon as two truly glorious failures – and, because of that, the two sides are probably more fondly remembered than if either one of them had actually triumphed. And there’s something nice but also sort of enigmatically cool about that. After all, ‘Total Football’ was a wonderful dream – and don’t all the best dreams fail in the end?

In contrast, Argentina had won their first World Cup – the congatulations were theirs. Yet, aforementioned controversies aside, there’s more to why I’m not fond of this particular tournament; much more. And it concerns the man who handed Daniel Passerella the trophy after the final whistle: General Jorge Rafael Videla. The country’s leader thanks to his position as head of a miliary junta that had seized control just one year before, Videla was a tyrant of the worst sort. In truth, Argentina’s leadership had been unstable ever since the legendary Juan Perón was deposed by a coup in 1955, in which case one has to question FIFA’s decision to give this country hosting duties in the first place. Especially as, leading up to the tournament, there had been great doubts raised as to the viability and ethics behind it and offers had come from other countries, such as Holland, to host instead. FIFA’s reluctance to step in and do anything would come back to bite it royally on the arse, though, as the chairman of the organising committee General Omar Actis was bumped off – apparently because he spoke out about escalating costs.

Don’t cry for those Argentinians? Buenos Aires’ Naval Mechanics School today – the artwork on the railings speaks a thousand words

The reality was that Videla’s junta was sponsoring forced disappearances and assassinations within Argentina, ostensibly against left-wing figures, yet to to this day nobody knows how many people were affected or killed – the number is thought to be in the thousands, however. This campaign – effectively a campaign of terror – became known as the ‘Dirty War’ and was the backdrop then to the ’78 World Cup. To placate participating nations who were concerned about their teams’ safety if they went to the World Cup, Videla said that there would be no bloodshed during the tournament – apparently, this was good enough for FIFA. Perhaps rightly so, Holland had called for a boycott before they, obviously, relented. Meanwhile, German Paul Breitner (who had scored a penalty in the ’74 final) wouldn’t take part and for many years it was assumed this too was the reason for Cruyff’s absence.

In perhaps the most stark summation of the situation, it has been said that inmates in Buenos Aires’ infamous Naval Mechanics School, which was used as a concentation camp at this time and is located only about a mile away from the Estadio Monumental, could hear the roars of the crowd during the final. While the football was generally good and the tournament entertaining, the off-field reality of this World Cup was simply monstrous, to my mind.

Indeed, years later ’78 World Cup winner Leopoldo Luque admitted: “With what I know now, I can’t say I’m proud of my victory. But I didn’t realise; most of us didn’t. We just played football.” He has also said: “In hindsight, we should never have played that World Cup. I strongly believe that.”

Not since Mussolini’s grandstanding of fascism when Italy hosted the competition in 1934 had the ugliness and evil the real world can create impinged on and blighted a World Cup – let’s hope it never does so again.

Motorcycle emptiness: Dennis Hopper, RIP

Cool runnings: Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda ride their hogs into history in Easy Rider

He was a maverick, a one-off, a seemingly indestructible hell-raiser, but on Saturday he proved to be just as fallible as everyone else. Dennis Hopper, an iconic figure who co-created a classic slice of counter-culture cinema and continued to cut his self-styled swathe through Hollywood for a further four decades has died from prostate cancer, aged 74.

He was born on May 17 1936 in Dodge City, Kansas, USA, his father having served in the US Government’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner to the CIA. Growing up in San Diego, the young Dennis developed an interest in acting and studied at the Old Globe Theatre, then, as a young man, moved to New York City and enrolled at the Actors Studio under the legendary Lee Strasbourg, whom he studied under for five years. While there he befriended British actor Vincent Price, whose interest in art rubbed off on Hopper too.

His acting career took off in the ’50s with appearances in TV dramas – among them Bonanza, Gunsmoke and The Twilight Zone – and he successfully moved into film, appearing most notably in Rebel Without A Cause (1955), Giant (1956), Gunfight At The OK Corral (1957), The Sons Of Katie Elder (1965), Cool Hand Luke (1967), Hang ‘Em High (1968) and True Grit (1969). Even at this early stage of this career, he had already developed a reputation for being difficult and, in later years, would credit John Wayne for revitilising his career by ensuring he was cast in The Sons Of Katie Elder owing to his mother-in-law being a friend of the Hollywood giant.

In 1967, Hopper starred in cult film The Trip. Directed by low-budget filmmaker supremo Roger Corman, the lead role was taken by Peter Fonda – son of Henry and brother of Jane – and it was written by relative unknown Jack Nicholson. Featuring a hallucinogenic sequence (hence its title), the movie made great use of psychedelic effects; this and its subject matter and tone made it something of a precursor for what would come next for Hopper. It was, of course, Easy Rider.