Crazy for it: Wimbledon, the littlest club in FA Cup-winning history, did a David-and-Goliath job over Liverpool in ’88, but which other Wembley wonders have made it on to the list…?

So, the FA Cup Final’s not what it used to be, eh? Its status as football’s ‘special’ one-off showpiece occasion has been seriously dented over the last 15 or so years by the rise of the Champions League and its final at the end of May every year, so they say. And, lest we forget, this year to accommodate that event taking place at Wembley, for supposed pitch-recovery reasons the Cup final is being held a week before the end of the Premier League season – sacriledge, cry the traditionalists!

Well, when it comes to the FA Cup, I’m a bit of a traditionalist too – or rather a nostalgist. I love the notion of the underdog succeeding and all the romance of the Third Round – and, yes, ideally I’d like the Cup final to come after the country’s top division has closed down. Like it or not, that’s definitely not what we’ve got this year, folks.

What we do have, though, is a Cup final that genuinely offers something of a welcome change. Or, in my eyes it does, at least. How so? Well, this year’s match will ensure for only the second time in, yes, a full 20 years none of the recent ‘big four’ (Manchester United, Chelsea, Arsenal and Liverpool) will run out winners of the Cup. Yes, it could be Man City who lift the Cup on Saturday – all right, they’re essentially the ‘new Chelsea’ with all their Arab-backed funds right now, but, hey, they haven’t been in a major final for 30 years. Or it could be Stoke who triumph come 5pm-ish – they haven’t won anything in 40 years. And, who knows, it could even be a decent match too. That would be something.

Talking of decent FA Cup finals, I’m afraid I couldn’t help myself, peeps… yes, I’ve had a trawl back through the old memory banks and, in recognition of Saturday’s (should be) finale to the English football season, have put together here a recollection of the best Cup finals – just for you good people. So I hope there’s no silly big-day-haircuts out there and all of you follow form and sing the national anthem and Abide With Me as you line up; if so, let’s kick-off this celebration of silverwear-seeking soccer history, shall we…?

Click on the highlighted match scores below to see clips of the action

Blackpool 4 : 3 Bolton Wanderers (1953)

The place: Wembley Stadium, London, England

The patter: The ‘Matthews Final’ aka the classic old-fashioned Cup final. The first to be attended by The Queen herself and to date the only Wembley Cup final to feature a hat-trick (thanks to Blackpool’s Stan Mortensen), it’s rightly remembered though for the brilliant play of 38-year-old, vegetarian teetotaller ‘wing wizard’ Stanley Matthews. His side trailing 3-1 with 22 minutes to go, Blackpool’s Matthews created two of the goals that turned around the tie and won it. It was his third (and surely final) chance of winning an FA Cup final – and he took it. That’s not all, mind, in netting on the day, Bolton’s legendary forward Nat Lofthouse managed to score in every round of the Cup that season. It’s said that at the final whistle, although on the losing side, he stood and applauded Blackpool and (no doubt in particular) Matthews’ achievement. What a game.

The man of the match: Duh, Stanley Matthews, silly.

The moment of the match: The winning goal – Matthews crosses into the box and Bill Perry meets it to seal The Seasiders’victory.

Words to the wise: What Ian Holloway wouldn’t give for that man Stan in Blackp0ol’s starting line-up right now, eh…?

Arsenal 2 : 1 Liverpool (1971)

The place: Wembley Stadium, London, England

The patter: Are you watching, Arsène? This is how you do it. Yes, it’s the match through which Arsenal clinched their first domestic double. All three goals came in extra time – the second, Arsenal’s first, was the first FA Cup final goal to be scored by a substitute; Eddie Kelly being the history man. Arsenal’s second goal is much better remembered though, it being the winner. It was a long range effort from surely the football equivalent of pop music’s one-hit-wonder, loveable, long haired, lanky Cockney, Charlie George.

The man of the match: Charlie George

The moment of the match: The Shaggy look-alike lies on his back after scoring the winning goal, arms outstretched in celebration.

Words to the wise: Whatever happened to Charlie George? No really, what did happen to him…?

Sunderland 1 : 0 Leeds United (1973)

The place: Wembley Stadium, London, England

The patter: The first proper Cup final upset of the modern era. Believe it or not, this Sunderland team remains the last-but-two-side to win the Cup from outside English football’s top division. And they did it against the 1970s’ ‘mighty’ Leeds to boot. Indeed, it only took one boot to do it – Ian Porterfield scored the single goal in the 31st minute. As glorious a moment in the history of Sunderland as whenever Lauren Laverne smiles on the telly.

The man of the match: Sunderland keeper Jimmy Montgomery, whose multiple saves preserved his side’s slender lead to the end.

The moment of the match: Montgomery’s diving-Gordon-Banks-versus-Pelé-in-1970-like save from Leeds forward Peter Lorimer in the second half.

Words to the wise: You know, I could swear Sunderland’s captain that day was the little one out of Cannon & Ball…

Southampton 1 : 0 Manchester United (1976)

The place: Wembley Stadium, London, England

The patter: And here’s the last-but-one side from outside the top flight to win the Cup (West Ham were the actual last in 1980). Granted, the Manchester United that Southampton beat here wasn’t the Charlton-Best-Law superstar stuffed side of just a few years before, but it was still Man United, who had still finished third in the First Division and Southampton (who’d finished more than 20 league places below them) still pulled off a humungous upset by claiming the Cup in their stead. It remains The Saints’ only major trophy triumph.

The man of the match: The brilliantly old-school-named Billy Stokes, scorer of the game’s only goal.

The moment of the match: That man Stokes netting with just eight minutes to go.

Words to the wise: It was the day the Saints bested the Devils. I thank you…

Arsenal 3 : 2 Manchester United (1979)

The place: Wembley Stadium, London, England

The patter: Two colossuses of English football collided here and, unlike in similar Cup finals of recent years, didn’t disappoint; yes, they provided goals, goals, goals. And then more goals. In all truth, though, it had been a bit drab until the 86th minute. Looking comfortable with a 2-0 lead from the first-half, Arsenal were cruising, but then Scot midfielder Gordon McQueen and Northern Irish international Sammy McIlroy scored in very fast succession to level the match. Amazingly, though, Arsenal spared their blushes, thanks to striker Alan Sunderland finishing off a break-away move and winning them the Cup with just one minute to go. It was rightly dubbed the ‘five-minute final’ by the media.

The man of the match: Alan Sunderland, the main man with the curly lion’s mane.

The moment of the match: After stretching to slot home the winning goal, Alan Sunderland wheels away at high speed, his face contorted in delight à la Marco Tardelli in the ’82 World Cup.

Words to the wise: Better late than never…

Tottenham Hotspur 3 : 2 Manchester City (1981, replay)

The place: Wembley Stadium, London, England

The patter: It was a Thursday night and, frankly, given the original match hadn’t be a stunner, this replay didn’t promise much. But thank goodness the introduction of penalties to decide a major final instead of falling back on a replay hadn’t happened yet, because on this Thursday night we’d have missed out on… well, only the greatest FA Cup goal of all-time. Even before that terrific moment, the match had been a bit special. Within the first 10 minutes both Tottenham’s Argentine import Ricky Villa and Man City’s Steve Mckenzie (with a thunderbolt of a volley) had scored. Then, in the second-half a penalty put the latter side in front, only for Garth Crooks to equalise with 20 minutes to go. And then it happened, six minutes later, Villa (inexplicably wearing the number five shirt – surely back then a centre-back’s number?) jinked past three players in the City box and struck home to win Spurs the Cup and go down in Wembley lore as scorer of the best goal ever witnessed at the stadium. Until Gazza scored for England against Scotland in Euro ’96, of course.

The man of the match: Ricky Villa, obviously.

The moment of the match: Ricky Villa’s goal, obviously.

Words to the wise: Diego who…?

Coventry City 3 : 2 Tottenham Hotspur (1987)

The place: Wembley Stadium, London, England

The patter: Spurs versus Coventry – why did the latter bother to turn up? Spurs were packed full of stars (Hoddle, Waddle, Ardiles and Clive Allen), had finished third in the league, and reached the League Cup Semis; Coventry had no famous names apart from the legendarily long-careered Steve ‘Oggy’ Ogrizovic in goal and an ageing Cyrille Regis in attack – oh, and hadn’t won anything after 104 years in existence. But, not only were the ultimate odds overturned, also – in a bit of a surprise – these two combatants delivered a top quality match. Scoring his 49th goal of the season, Allen put Spurs in front after just two minutes, but Coventry equalised five minutes later through midfielder Dave Bennett. Five minutes before the break, Tottenham captain Gary Mabbutt struck to put them ahead again, only around the hour-mark for Bennett to deliver a top cross and Coventry forward Keith Houchen to put it away with a diving header (a goal voted the season’s best in a BBC poll, in fact). Yet, as so many great matches do, this one had a sting in the tail, or rather in a knee, as it was off Mabbutt’s patella that in extra-time the ball deflected and ended up in the Coventry net to hand the Midlanders an unlikely, but wonderful triumph. Indeed, so enduringly delighted with this slice of (bad) luck were the Coventry fans that years later one of their fanzines was still called ‘Gary Mabbutt’s Knee’.

The man of the match: Gary Mabbutt, of course – few players can claim to have scored twice in a Cup final, let alone at both ends.

The moment of the match: Coventry manager John Sillett dancing on to the pitch at the final whistle.

Words to the wise: Actually, why did Spurs bother turning up for this final? I mean, there’s no “1” in the year “1987”, is there…?

Wimbledon 1 : 0 Liverpool (1988)

The place: Wembley Stadium, London, England

The patter: Right, despite what happened the year before, this one would definitely be a cake-walk. Er, wouldn’t it? Liverpool were without question the side of the ’80s – they almost won every major domestic trophy going each season in that decade. Seriously. So when the already League Champions lined up against the lowly (but top league club) Wimbledon, there could only surely be one result. Wimbledon, though, unforgettably were the self-styled ‘Crazy Gang’; a team of practical jokers that was so tightly-knit they looked like a cross between East End wannabe hoodlums and the Marx Brothers. Perhaps we shouldn’t have been surprised then when on 37 minutes forward Lawrie ‘The Spaniard’ Sanchez headed them in front. Liverpool threw everything and the kitchen sink and even an on-the-hour John Aldridge penalty at them (brilliantly saved by keeper Dave Beasant – the first ever Cup final penalty save), but it was no good; Wimbledon pulled off their biggest gag of all and left egg all over Dalglish and his cohorts’ faces.

The man of the match: Dave ‘Captain Fantastic’ Beasant

The moment of the match: It should be the goal, but really it’s the save. Actually, scrap that; it’s really at the end watching Wimbledon lift the Cup – it’s like watching a major sporting triumph in a parallel universe.

Words to the wise: Arsenal haven’t won a trophy in six years and can’t win at Wembley? Time to buy up the ‘Crazy Gang’, Arsène…

Liverpool 3 : 3 West Ham United (2006, Liverpool won 3 : 1 on penalties)

The place: The Millenium Stadium, Cardiff, Wales

The patter: Quite simply, the greatest Cup final of modern times. By a distance too. Having spectacularly come back from 3-0 down to win the European Cup the season before and having finished third in the league this time, Liverpool were hot favourites against a nevertheless talented West Ham side (who’d finished ninth that season). It was hugely against expectations then when – thanks to, first, a Jamie Carragher own-goal and, second, a goalkeeping fumble by Pepe Reina allowing forward Dean Ashton to tap in – the underdogs claimed a two-goal lead inside half-an-hour. Just four minutes later, though, and a pin-point ball from Liverpool’s captain Steven Gerrard was met by striker Djibril Cissé and the favourites clawed a goal back. Shortly after half-time they were level thanks to a stonking Gerrard volley, but ten minutes later a marvellously flukey, looping cross from the boot of Paul Konchesky put The Hammers back in front. That was it, surely; the Cup was West Ham’s? Nopes, in the 90th minute, Gerrard drove a 30-yard screamer into the bottom corner to equalise for a second time. Extra-time came and went with little incident and, just as they had in the Champions League a year before, Liverpool won the trophy through the penalty shoot-out, in which their keeper saved three times. Far from the upset then it looked it would be twice, but a spectacular, wholly satisfying Cup final nonetheless.

The man of the match: In any other match, Konchesky or Reina would be sure-fire candidates, but clearly Gerrard played out of his skin in this game – unlike in the World Cup that summer unfortunately.

The moment of the match: Gerrard’s audacious second equaliser.

Words to the wise: Ah, back in the days when West Ham could go toe-to-toe with the best – clearly had Scott Parker been in their side, they’d have trounced Liverpool. Erm, well, you know…

And possibly the worst…?

Chelsea 2 : 1 Leeds Utd (1970, replay)

The place: Old Trafford Stadium, Manchester, England

The patter: Probably the most controversial Cup final, this one is deemed by some – the misty-eyed nostalgics among them – as an iconic example of the rough and tumble era of English football, but by others as a bad-tempered, overly aggressive and sad indictment of the nation’s favourite sport at the time. And it certainly was the nation’s favourite, after a rambunctious first match at Wembley, which ended 1-1, the second- and third-placed clubs in the First Division met days later and 28 million people tuned in… to see them kick even more lumps out of each other. The culprits were the most likely ones; for Chelsea, captain Ron ‘Chopper’ Harris and Eddie McCreadie and, for Leeds, captain Billy ‘The Red-Headed Tiger’ Bremner and Norman ‘Bite Your Legs’ Hunter. Despite ill-timed crunching tackles, head-butts and kneeings, no red cards and only one yellow card were shown. Modern-day referee David Elleray (admittedly a real football disciplinarian) claims, had he overseen the match, he’d have sent six players off and shown 22 yellow cards. Well, there you go. Chelsea won the Cup by the way and, in doing so, qualified for the European Cup Winners’ Cup the following season and won that too.

The worst man of the match: An England hero back in ’66, Jack Charlton was as guilty as anyone when it came to putting the boot and head in and, in following the wrong player to exact retribution for a previous come-to, left Peter Osgood on his own to head in Chelsea’s equalising, first goal.

The worst moment of the match: Probably Hunter and Chelsea’s Ian Hutchison trading punches as if they were in a boxing ring.

Words to the wise: At least this wasn’t the real climax to the football season that year; nopes, just two months later World Cup ’70 would kick-off – now that’s what you really call a result…

Made my mind up: Eurovision’s top 10 tunes

Promise to love you forever more: thanks to their performance of the wonder that is Waterloo at 1974’s Eurovision, Sweden’s ABBA were soon to become an irresitible global phenomenon

Kitsch, camp, continental and, more often than not, dafter than a Russ Abbot sketch, The Eurovision Song Contest nowadays finds itself in the – if you ever bother to think about it – somewhat befuddling position of being both reviled and adored in equal measure. But back in the day, that most certainly wasn’t the case.

Granted, if you were to head back a few decades to its heyday in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, it probably didn’t boast the obsessive levels of devotion it now seems to have among its hardened, ardent band of fans who adore it for all its naffness and absurdity, but back then it was genuinely very popular as a family-oriented spectacle for the masses – rather in the manner that a pre-women’s-lib telly audience lapped up Miss World. And nowhere was that more true than right here in Blighty. Indeed, that’s probably no surprise actually, as once, twice and maybe a few more times, Eurovision came up trumps and delivered a decent tune for the ears of the European public – in addition to all the ghastly ones it inflicted on them too, of course.

So, what with the latest annual, televisual, Europe-wide assault on the senses coming up on Saturday, here’s my salute to the very best offerings Eurovision has managed to serve up for us over the course of its 55-year history – oh, and do click on the song titles to hear them, folks, really, they’re not that bad; well, all right, some of them aren’t…

10. Congratulations ~ Cliff Richard (UK, 1968)

Despite not ending up winner on the night (it came second), this has to be one of the all-time most well recalled Eurovision ditties. But why? Well, first, no doubt it’s down to the Cliff factor; love or loathe him, the Peter Pan of pop is undoubtedly one of the biggest stars to have ‘graced’ Eurovision. And, second, it’s got to be the tune’s recognition factor. No question, that chorus can bore into your brain like a tunnelling mole turning a hand-drill in your ear. So, if it’s over-familiar and, frankly, over-irritating, how come it deserves a place in this top ten? Well, just check out the garb worn by Cliff and his backing singers; if this performance wasn’t the inspiration for that Austin Powers blue suit and the Fembots’ dresses-cum-nighties, then I’m Cliff’s Dutch uncle.

9. Boom-Bang-A-Bang ~ Lulu (UK, 1969)

I’ll be honest, the Glaswegian-pop-kitten-turned-QVC-self-branded-schlock-shifter has never really been among my favourite chanteuses (even if she did perform one of John Barry’s Bond themes), but as far as Eurovision goes, her effort from 1969 is one of the classics. Not only does it possess a mildly and whimsically appealing innuendo for a title and a brilliant knockabout chorus that bounces all over the shop, but it can also lay claim to being one of the UK’s few Eurovision winners – well, along with the songs that in 1969 each represented Spain, France and The Netherlands, of course. Yes, that’s right, that year four songs all finished top of the pile. It could only have been the late ’60s, couldn’t it?

8. Hard Rock Hallelujah ~ Lordi (Finland, 2006)

The most unlikely Eurovision win ever? Well, back in the day the idea of a ‘hard rock’ act triumphing at the world’s biggest middle-of-the-road music contest would have been unthinkable; by the middle of the Noughties, though? Like I said in my introduction above there, and as many of us are aware of course, Eurovision nowadays wilfully wallows in its high kitsch hijinks and hugely camp capers, so as it turns out, maybe this victory wasn’t the craziest outcome imaginable. Plus, let’s not kid ourselves, Lordi are hardly a serious metal band; sure, they dress up like orks out of Lord Of The Rings and their guitar-driven sound is heavy, but frankly they’re more a Black Lace than a Rage Against The Machine. And that goes for this tune too; it’s actually quite a hummable, humorous, entertaining effort – rather like most Eurovision winners then. The Fins must’ve been so proud. Probably.

7. Making Your Mind Up ~ Bucks Fizz (UK, 1981)

Had Bucks Fizz’s Making Your Mind Up not featured the now iconic long-skirts-ripping-off-to-reveal-short-skirts-underneath move, would it have won the 1981 contest for the UK? Not likely. More importantly, had it not featured this unforgettable moment from Eurovision history, would it have made this top ten? Unquestionably not. In fact, had it not featured it, the whole effort would’ve be rubbish. Let’s not beat around the bush, this tune is, well, pretty dreadful – an up-tempo, irritating-as-hell rock ‘n’ roll throwback complete with off-key singing and clichéd-to-the-hilt dancing from the garishly costumed Fizzers (hand jives included). Yet, that second of sauciness still strangely satisfies, or even delights. There’s something pleasingly subversive about it, knowing it came from such a family friendly show in a more innocent time (even if it was the year in which both Body Heat and The Postman Always Rings Twice were released). Yup, Bucks Fizz did it; they brought the prize home for Britain and ripped those skirts off. Thank goodness for Cheryl Baker’s legs, eh?

6. Guildo Hat Euch Lieb! (Guildo Loves You All!) ~

Guildo Horn & Die Orthopädischen Strümpfe (Germany, 1998)

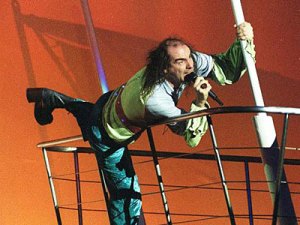

Eurovision enthusiasts will be quick to point out that 1998’s shindig is best remembered for Israel’s Dana International winning with the dance track-esque Diva. First, when was Israel ever in Europe? Second, rare trans-sexual media sensation she may be, but Dana International was not the highlight that evening. That honour, mein lieben, went to the wonderfully wacky Guildo Horn and his Die Orthopädischen Strümpfe (Orthopaedic Stocking). Honestly, words simply cannot describe my delight that night as on my TV I watched this pseudo-’70s-throwback-togs-disrobing, head-kissing, splits-performing and stage-set-climbing cartoon character deliver a routine of so-bad-it’s-good party pop, which even (and entirely nonsensically) halfway through included the ringing of a line of little Alpine bells. This was the first year TV viewers themselves could vote for their favourite entries – I voted for Guildo twice. Apparently, Dana International’s returning to Eurovision this year with a song called Ding Dong. Who cares? Bring back Guildo!

5. Save Your Kisses For Me ~ Brotherhood Of Man (UK, 1976)

Remember I said above Eurovision used to enjoy being middle-of-the-road? Well, this one confirms it. Not only did it win, it went on to become a huge hit – it was #1 in the UK for six weeks, ensuring to this day it’s the biggest ever selling Eurovision tune. Its performers, the inoffensive pop-driven quartet Brotherhood Of Man, were a staple of Britian’s pre-punk popular music scene too (even more so after their triumph here in The Hague) and, love to hate ’em as you may, you can understand why. With their boy-girl-boy-girl line-up, half of which was a pair of hotties, and their tight routine, both in terms of the melody and harmonies and that pleasingly silly/ unforgettably annoying (delete as appropriate) arms-bent and knee-lifting dance, they were professional to the hilt. The song’s appealing too somehow; incredibly catchy and unashamedly cheery (with its dotty lyrical twist at the end), it seems to fit perfectly with that whimsically recalled, hot British summer that would never end in ’76. Plus, the group’s moustachioed one… with his chest hair and bling, there’s something of the rather naff, lechy ladies’ man at the end of the bar at Butlins about him. And, right or wrong, that rather tickles me.

4. Vivo Cantando (I Live Singing) ~ Salomé (Spain, 1969)

This effort is truly awesome. Deservedly, it was one of the three songs to finish joint top along with Lulu’s Boom-Bang-A-Bang back in ’69 (see above); but it surely should have won outright. It’s the best example of show-tune inspired, brass-backed, old-school Euro pop you’ll hear all day. No, all week. Actually, make that all year. Honestly, I defy you not to get pulled in and pumped up – or at least find a smile crossing your chops – as this crazy melody speeds up towards it’s hurly-burly climax. It’s brilliant fun. And much of the credit must go to the game Salomé, who’s so full of vitality here she’s a virtual matadoress. Her get-up is something to behold too; in a shaggy, blue, figure-hugging outfit that makes the most of her ample assets, she looks like some sort of sexy Mediterranean yeti. Probably she is – this whole thing’s so gloriously nuts, I wouldn’t be surprised. All together now: Pa-para-para-papaaa, pa-para-para-papaaa…!

3. Puppet On A String ~ Sandie Shaw (UK, 1967)

Ah, Sandie Shaw… the barefoot bambino of Swinging ’60s pop. Made in Dagenham, quite literally, she oozed sexy, East End cool and had chart-hit-after-chart-hit, including Bacharach and David’s unforgettable (There’s) Always Something There To Remind Me. So how the hell did she end up doing tacky old Eurovision? Good question. Well, by 1967, somewhat bizarrely, her star was beginning to fade and her manager felt a more cabaret-like direction was what Sandie needed. The artist herself was less than sure and far from sure about the song she ended up performing at Europe’s campy televisual spectacular (of the five tunes she sang on The Rolf Harris Show for the public to choose, the winner was bottom of her list – she’s said of it: “I hated it from the very first oompah to the final bang on the big bass drum. I was instinctively repelled by its sexist drivel and cuckoo-clock tune.”). Yet, fate’s a funny old thing. Shoeless Sandie gave her all and delivered a performance with real polish – despite her microphone cutting out at the start – and guess what, yes, silly little Puppet On A String proved the runaway winner on the night and gave the UK its first ever Eurovision victory. And it was ready, steady go for Sandie once more too – the song became her third #1 in Britain and a worldwide hit, notching up in excess of a million sales and thus achieving gold disc status. And, despite her reservations, she even re-recorded it to mark her 60th birthday in 2007.

2. Waterloo ~ ABBA (Sweden, 1974)

You may well end up wondering on Saturday night, as you watch this year’s Eurovision (if you can face doing so yet again, of course) just what it is that really, genuinely does redeem this 55-year-old monolithic celebration of musical murk. Well, folks, this is it – by rewarding a very little known four-piece from Scandinavia with top honours back in 1974, Eurovision can rightly claim to have set ABBA on their way. Yup, it was the classy, quality performance by Agnetha (the blonde one), Anni-Frid (the redhead one), Björn (the beardy one) and Benny (the other one) of the irresistible Waterloo that April evening at the Brighton Pavilion that created the Swedish meatball (sorry, snowball) that would get bigger and bigger and, yes, better and better as it hurtled its way through the charts and arenas worldwide during the ’70s. When released as a single, Waterloo topped the charts in the UK, West Germany, Ireland, Belgium, Norway, Finland, Switzerland and South Africa. It was also a #3 hit in France, The Netherlands, Spain and Austria, as well as reaching a high of #6 on the US charts (the only Eurovision song to have made the Top 40 over the pond – clearly the Yanks have some taste when it comes to Eurovision). Honestly, is there anything negative to say about this tune? Well, my Dad has always said it’s the worst song ABBA ever released. He has a point, it’s not their best; but their worst? That’s a little harsh, methinks – I mean, by Eurovision standards it’s the Mona Lisa. Still, at least they didn’t go with its original name ‘Honey Pie’; had they done so, they may well have met their Waterloo in Brighton that night and – mamma mia! – pop music history could have turned out very differently indeed.

1. Love Shine A Light ~ Katrina And The Waves (UK, 1997)

They say you remember where you were when you heard that a momentous event in history had just taken place. For me, one such occasion was when I heard the UK had won The Eurovision Song Contest for the first – and, so far, only – time in my living memory (yes, all right, ‘momentous’ may not have been quite the right adjective to use in the first sentence there, but anyway). I was at a friend’s 18th birthday party watching her enormous dog eat a dishful of sausages off a table when her dad came into the room and told the gathered adolescent throng that ‘we were winning Eurovision and nobody was going to catch us’. So unlikely, nay incredible, a proposition was this that we hurried into the lounge to discover that, lo and behold, he wasn’t joking; he was absolutely right. If 1997’s competition had been that map of Europe which appears in the opening titles of Dad’s Army, then Katrina And The Waves (beforehand a relic of the previous decade thanks to 1985’s one-hit-wonder Walking On Sunshine) would have sent Union Jack-arrows speeding to every corner, nook and cranny of the Continent, so indubitable was their song the night’s winner. Not only did it receive a total of 10 maximum 12-point-votes (douze points), it also accumulated such a large point-total that it held the record of most points ever scored by a single song (227 out of 288) for 11 years.

Plus, lest we forget, over here the win felt like it was riding on a wave of the old British ‘feelgood factor’ – yep, Union Jacks were everywhere as Tony Blair’s New Labour had just swept to power on May 1. Winning singer Katrina Leskanich observed that it was the second landslide of the week (it was the second in 48 hours, in fact). Oh yes, Britpop was here, Blair was in and we’d won Eurovision – Blighty was fantastic again. Granted, it all turned to crap, as it always inevitably does, but youth music movements and politics aside, they can never take that glorious Eurovision victory away from us nor the glorious song behind it. For that’s what Love Shine A Light is – a bloody good song, plain and simple. It’s anthemic pop at its finest; I defy you not to be lifted up at least a smidgen whenever that chorus rises. After all, all those Eurovision chaps back in ’97 did and they clearly know their music, don’t they? Er, all right, don’t answer that.

Eurovision Song Contest 2011, Saturday, 8pm, BBC1 (HD) and BBC Radio 2

(UK and Northern Ireland only)

Clenched fists: Seve Ballesteros delivering his classic celebration following another bravura performance (left); Henry Cooper in a typically impressive pose for the cameras (right)

Sadly, it’s time for another obituary here at George’s Journal – in fact, it’s time for two of them. Yes, a pair of unquestioned icons have passed on, both from the world of sport – and surely the much wider world will be a lesser place for their absence. Both Seve Ballesteros and Henry Cooper, in very different yet very individual ways, irreparably changed their sports – and changed them for the better.

Severiano ‘Seve’ Ballesteros Sota, who died just yesterday aged 54, was born on 9 June 1957, in Pedreña, Cantabria, Spain. Always destined to be a professional golfer (his uncle was Spanish champion four times and finished sixth in the 1965 US Masters tournament, while all three of his older brothers also turned pro), the young Seve practically taught himself how to play the sport on the beautiful beach behind his house. He also sneaked on to the Pedreña golf course at night to practice and, aged 12, he shot a score of 79 to win the course’s caddies’ tournament.

In 1974, at just 16-years-old, he turned professional and came to prominence two years later when he led the British Open for the first three days – ultimately finishing tied second with the legendary American player Jack Nicklaus. However, by the end of that year he had managed to claim the European Order Of Merit title (meaning he was the continent’s best player), the first of three successive times out of a total of six times. His first great triumph came in 1979, though, when at 22 he became the century’s youngest golfer to win the British Open – now his fame was unquestionably global. Not least, because on the 16th hole his tee shot had landed in a car park, yet he’d still managed to birdie the hole (finish one-under-par).

In total, Ballesteros won five golf ‘Majors’ (of which there are four; the British Open, the US Open, the US Masters and the PGA Championship); he added another two British Opens to his first (1984 and ’88) and two Masters (1980 and ’83). Indeed, he was amazingly the first European player to win a Major since 1907 and, in winning his first Masters title, he led by 10 holes with nine to play. Unsurprisingly, during the ‘8os he often was rated the world’s #1 golfer; in the late ’80s he constantly vied with Australian Greg Norman for the top spot. His indelibly competitive spirit helped him also win five World Match Play tournaments between 1981 and ’91.

Standing ovation: Seve, at just 22, takes the plaudits as he wins the British Open on 21 July 1979

However, perhaps more important than this, during his career Seve was arguably the world’s most popular golfer too. His approach to playing the game was full-on, all-out, exciting-to-the-hilt and utterly captivating. He may have been an aggresive player who loved to take risks, but his on-course personality was just as magnetic – he was a charismatic tour de force. Perhaps American golfer Tom Kite put it best by saying: “When he gets going, it’s almost as if Seve is driving a Ferrari and the rest of us are in Chevrolets”. It didn’t hurt either that off the course he was an amiable, fairly humble chap and a committed family man.

He also seemed to lead a wave of European success in golf, a sport in which America had held the upper hand for decades. This was to be seen individually (with the UK’s Nick Faldo, Ian Woosnam and Sandy Lyle and fellow Spaniard Jose-Maria Olazabal all winning Majors) and collaboratively. In 1979, if good enough, any European golfer was invited to join the British and Irish side in the Ryder Cup team event against the Americans – Ballesteros was, of course, included. Although dropped in ’81, Seve returned and in ’85 was the driving force behind the Europeans’ first victory in the competition for 28 years. Two years later, the Europeans won again, this time on US soil. In total he won 20 points out of a total 37 in his eight Ryder Cups – and his partnership with Olazabal is still the event’s most successful. In 1997 he was the Europeans’ non-playing captain (essentially the team’s coach) when the thing was held in Spain – they won again.

With 87 professional victories behind him, Ballesteros’s form and appearances waned during the ’90s owing to arthritic back and knee problems. His final effort came at the Masters in 2007, where he sadly finished last. On 12 October 2008, he announced to the world that he had been diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. He underwent an operation and extensive treatment, which he battled with his trademark bravura, but ultimately, of course, his neurological condition worsened and finally took his life.

Before his death, he established the Seve Ballesteros Foundation, which aims to help fight cancer, especially brain tumors, and financially aid young golfers. He leaves behind his wife, two sons and a daughter. On hearing of his passing, current world #1 golfer, Britain’s Lee Westwood said: “Seve made European golf what it is today”.

~~~

One of the UK’s most popular ever sportsman (his nickname, after all, was ‘Our ‘Enery’), Henry Cooper died aged 75 on May 1. He began his boxing career in 1949 and, as an amateur, won 73 out of 84 fights – two of which earned him a pair of ABA (Amateur Boxing Association) Light-Heavyweight titles. He was born, along with his twin brother George – who also grew up to be a boxer – on 3 May 1934 in South East London. During World War Two, his father was called up to serve his country, while Henry and George went to school in Lewisham, the playground of which was, in fact, the site of Henry’s first knock-out. The twins actually excelled in many sports while at school, including football and cricket.

After competing in the 1952 Olympics and two years’ national service in the Royal Army Ordnance Corp, Henry turned professional at the same time as George (who competed under the name Jim Cooper). He experienced early setbacks when challenging for titles, but eventually took the British and Commonwealth Heavyweight titles from Brian London in a 15-round decision in January 1959, aged 24. Having won this fight, he was free to face the World Heavyweight Champion, Floyd Patterson of the US, but deciding he wasn’t ready, he turned down the chance and opted instead to defend his twin titles against all comers. Towards the end of his career, he held the British, Commonwealth and European Heavyweight titles all at the same time.

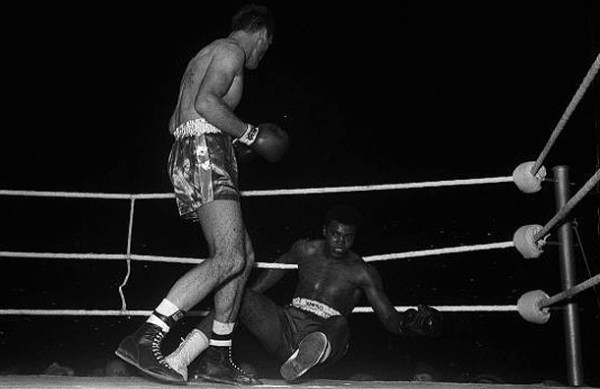

In 1963, Cooper took on his most famous opponent in his most famous bout, namely Cassius Clay (later, on his conversion to Islam, to be Muhammad Ali). A gold medal winner at the 1960 Olympics, Clay was a young, but heavier, faster and most formidable foe, even if the the meeting was a non-title fight. And, most memorable of all, it was during this match that Cooper knocked-down arguably the greatest boxer to have lived. At the end of the fourth round, he caught Clay with an upward-angled version of his trademark left-hook punch (this was nicknamed, unsurprisingly, ‘Enry’s ‘Ammer). Luckily, Clay caught his armpit on the ropes and so didn’t hit the canvas floor and controversially was given smelling salts in his corner during the break that followed, which ensured he recovered. Catching Cooper below the eye and causing it to bleed, Clay won the fight as the referee had to stop the contest – Cooper had been ahead on the scoring.

Three years later, Henry got a shot at the big one when he met the now monikered Muhammad Ali, now World Heavyweight Champion, again. This time, though, Ali was wily to the danger posed by his opponent’s powerful left-hook and used his trademark smart footwork and other tactics to avoid it. A cut below Cooper’s eye opened up during this fight also and Ali won again – again Cooper had been ahead on points at the end. On the punch that had felled him in the first fight, Ali would later say on British TV that Cooper had hit him so hard that his ‘ancestors in Africa had felt it’.

It’s (nearly) a knock-out: Our ‘Enery almost puts Cassius Clay on his backside in their 1963 fight

Cooper went on to fight Floyd Patterson eventually, but was knocked-out in the fourth round. More happily, he defended all his titles until his last fight in 1971 against Hungarian-born-British-Australian up-and-comer Joe Bugner. The latter won the fight, and with it Cooper’s three titles, by a mere quarter of a point. Neither the heavily pro-Cooper crowd at the fight, nor the UK public, nor even the legendary TV commentator Harry Carpenter were much impressed; in his commentary, Carpenter exclaimed: “How can they take away the man’s titles like this?”. Cooper was now 36. He had fought 55 professional fights, won 40 and knocked-out 27 opponents.

Following the end of his boxing career, Cooper kept himself very much in the public eye and, unquestionably, in the British people’s hearts. Constant appearances on television – on the likes of the sport-themed quiz show A Question Of Sport and, notoriously, in the 1970s commercials for Brut cologne aftershave (one of them opposite the perma-permed Kevin Keegan: “splash it all over, ‘Enry”) – ensured he took on the mantle of a jolly, avuncular if still physically imposing figure. Indeed, Cooper’s out-of-the-ring upbeat, Sarf London personality had always endeared him to the public and continued to do so for the rest of his life – he once remarked that his wife, who apparently hated boxing, was the perfect boxer’s wife because she invited journalists in for a cup of tea while they waited for him to get out of bed on the morning after fights.

Henry Cooper was a hero from a different age – both in terms of boxing and in terms of the UK itself; an age that, even if it weren’t so, seemed nicer, simpler and fairer. Indeed, he was the first celebrity backer of the Anti-Nazi League, a high profile pro-immigration movement (as the grandson of an Irish immigrant he was vehemently against racism, despite being generally traditionalist in his other political views). He was also very much a working-class hero in an era when fellow working-class celebrities such as The Beatles and Michael Caine came through and captured the public imagination. Like these, Cooper was a permanent – and, looking back, a comfortable – fixture of Britain in the 1960s. It’s no surprise he was the first person to win the BBC’s Sports Personality Of The Year Award twice (1967 and ’70), in addition to receiving an OBE in 1969 and being knighted in 2000.

Over the years, he also did a great deal of charity work and even dabbled with acting, appearing in a cameo as a Victorian boxer in the film adaptation of the novel Royal Flash (1975). But – and thanks to all his familiar later years in the public eye, it’s easy to forget – it’s as a truly heady heavyweight boxer that he should and probably will be best remembered. In a sport whose summit was dominated by Americans for so long, he (like Seve after him, you might say) opened the door for the British once more. He was the first Briton to come close to winning the World Heavyweight title for decades, making it more than conceivable a Brit might actually do it. Unquestionably then, he paved the way for Frank Bruno and Lennox Lewis eventually getting the job done after him. And more, his knock-out personality won him lifelong fans from Lewisham to Carlisle. So long, ‘Enry – the epitome of the gentleman sportsman.

Playlist: Listen, my friends! ~ May 2011

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and enjoy…

CLICK on the song titles to hear them

~~~

Peter Cook and Dudley Moore ~ Goodbye-ee

The Monkees ~ Pleasant Valley Sunday

Traffic ~ Paper Sun

Elvis Presley ~ A Little Less Conversation (original version)

Vanessa Redgrave ~ The Lusty Month Of May

John Lennon ~ Isolation

Marvin Gaye ~ Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)

Tony Christie ~ Avenues And Alleyways (Theme from The Protectors)

Disco Tex And The Sex-O-Lettes ~ Get Dancin’

The Undertones ~ Teenage Kicks

Rufus and Chaka Khan ~ Ain’t Nobody

The Bangles ~ If She Knew What She Wants

Tears For Fears ~ Woman In Chains

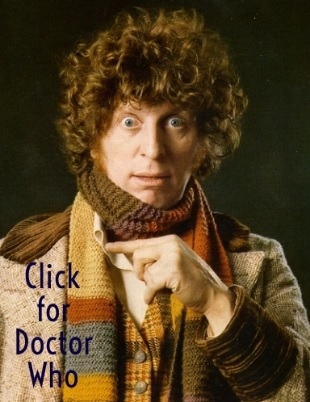

Easter geekness: the return of Doctor Who (April 23) and more egg-stra special delights

Cowboys and aliens?: Matt Smith’s take on The Doctor tests that old adage: ‘stetsons are cool’…

All right, I’ll admit that unlike its arguable heyday, it’s a bit of a stretch to suggest the modern Doctor Who is retro, although in recent years the show’s time-travelling hero has visited William Shakespeare, Queen Victoria, Charles Dickens, Vincent Van Gogh and 16th Century Venice. But that’s not really what this blog would consider as retro. Having said all that, mind, in its latest series, the TARDIS is supposed to land in ’70s America in the time of Richard ‘Tricky Dicky’ Nixon. Surely you can’t get much more retro than that, can you?

Anyway, why am I blathering on about Doctor Who? Well, guess what, chaps, Easter once more is on the horizon and that must mean – oh yes – the kick-off of the latest series of the Who Doctor. And, I don’t mind sayin’, I’m rather excited about it.

Now, don’t know about any of you, but of all his series since that groovy Gallifreyan returned to our screens in 2005, the last one (the opening series of the latest incarnation – the 11th – namely Mr Matt Smith’s), has been my favourite. The return of River Song and those eerie stone angels? Spitfires in space? A spruced up TARDIS? Cracks in time? The Pandorica? Toby Jones’s ‘Dream’ Doctor alter-ego? Top stuff, all of it. Plus, of course, there’s been Karen Gillan’s oh-so sexy Amy Pond companion and, best of all, Smith’s excellent young-yet-old-and-at-times-very-alien version of The Doctor. The Christmas special even gave us a nice take on A Christmas Carol with Michael Gambon and (mmm) Katherine Jenkins.

All of that means, of course, that the next series (which kicks-off on BBC1 at 6pm tomorrow – and on BBC America in the States on the same day) does have quite a lot to live up to. Yet, the omens look good. Apparently, this latest series is darker in tone than the last (at least, its start is supposed to be). Also, [spoiler alerts!] Amy and her squeeze Rory will be together in the TARDIS as marrieds – just how will that work out? And, so it seems from the trailer (see above), The Doctor and River Song’s fates are likely finally to become entwined – yes, I think you know what I mean there. Oh, and it looks like Lily Cole’s in it (again – mmm). All in all then, I’m hungry to hunker down with The Doctor once more. Which brings me to Easter eggs – if you’ve been of the mind that all the hype and publicity leading up to Easter and the May Bank Holidays has only been about a particular wedding, think again, peeps, because look what you can purchase from M&S…

Talking of Easter TV, at least on UK screens, there’s one or two other highlights to look out for too. Indeed, tonight you can sit down, watch and listen to an evening dedicated to Elton John (BBC4 from 9pm); and, if Reg Dwight’s ditties aren’t exactly your thing, then a documentary on George Martin (Arena, Monday, 9pm, BBC2) may be more up your street, no doubt featuring archive footage alongside interviews with past major collaborators of the genius producer. And, with the football season reaching its unavoidable zenith, there’s also an intriguing looking dramatic recreation of the events surrounding the Munich Air Disaster of 1958 in the shape of United (Sunday, 9pm, BBC2), featuring the acting talents of, yes, a past Doctor, that unbiquitous David Tennant.

So, certainly a few gogglebox treats there to gobble up your freetime over the weekend then, folks… or, of course, you could make the most of the weather and spend the holiday doing properly healthy things outside. Actually, scrap all that, maybe the latter is the better plan – after all, who knows what sort of summer we’re going to get? Happy Easter, my retro chicks.

~~~

Easter telly highlights (UK terrestrial and Freeview only)

Black Narcissus  ~ today, 2.40pm, Film4 Must-see, eerie drama about repressed desires surfacing among a group of nuns in the Himalayas, starring Deborah Kerr, Kathleen Byron and Jean Simmons

~ today, 2.40pm, Film4 Must-see, eerie drama about repressed desires surfacing among a group of nuns in the Himalayas, starring Deborah Kerr, Kathleen Byron and Jean Simmons

The African Queen  ~ today, 4.40pm, Film4 John Huston’s outstanding trip down an African river with a pair of ageing opposites, starring Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn

~ today, 4.40pm, Film4 John Huston’s outstanding trip down an African river with a pair of ageing opposites, starring Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn

Enchanted  ~ today, 4:50pm, BBC1 Disney live-action musical that riffs on its fairytale-schamltz-past less scathingly than Shrek, starring Amy Adams and Susan Sarandon

~ today, 4:50pm, BBC1 Disney live-action musical that riffs on its fairytale-schamltz-past less scathingly than Shrek, starring Amy Adams and Susan Sarandon

Grease  ~ today, 6.50pm, Film4 Seemingly unavoidable film version of the ’50s-set teen musical, starring John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John

~ today, 6.50pm, Film4 Seemingly unavoidable film version of the ’50s-set teen musical, starring John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John

Raiders Of The Lost Ark  ~ today, 7.10pm, BBC3/ BBCHD The first and best Indy flick – and, frankly, one of the best adventure movies of all-time – starring Harrison Ford, Karen Allen, Paul Freeman and John Rhys-Davies

~ today, 7.10pm, BBC3/ BBCHD The first and best Indy flick – and, frankly, one of the best adventure movies of all-time – starring Harrison Ford, Karen Allen, Paul Freeman and John Rhys-Davies

Elton John Night ~ today, 9pm, BBC4 Kicking-off with The Making Of Elton John: Madman Across The Water (also shown at 12.05am) Documentary about the musician’s career and life; Elton John At The BBC, 10pm, 3.05am Archive footage; Electric Proms, 11pm, 2.00am Performing at The Roundhouse, Camden, London; BBC Sessions 1.05am And yet more Elton John

Timewatch: The Real Bonnie And Clyde ~ today, 12.00midnight, BBCHD The true story of the legendary murderous lovers

Being Alice: Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland/ Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland ~ Saturday, 2pm/ 2.30pm, BBC2/ BBCHD The world premiere of a new ballet of Lewis Carroll’s classic tale from Covent Garden’s Royal Opera House, preceded by a behind-the-scenes look at its making

Hook  ~ Saturday, 3.35pm, Channel5 Spielberg’s colourful and watchable take on Peter Pan, starring Dustin Hoffman, Robin Williams, Julia Roberts and Bob Hoskins

~ Saturday, 3.35pm, Channel5 Spielberg’s colourful and watchable take on Peter Pan, starring Dustin Hoffman, Robin Williams, Julia Roberts and Bob Hoskins

Doctor Who ~ 6pm, BBC1 The latest series – and second with Matt Smith as The Doctor – of the sci-fi adventure drama kicks-off with its opening episode, The Impossible Astronaut

Time Bandits  ~ Saturday, 6pm, Film4 Terry Gilliam’s evergreen, off-kilter time-travel adventure starring Sean Connery, Ian Holm, John Cleese and Ralph Richardson

~ Saturday, 6pm, Film4 Terry Gilliam’s evergreen, off-kilter time-travel adventure starring Sean Connery, Ian Holm, John Cleese and Ralph Richardson

The Karate Kid  ~ Saturday, 7pm, 5* Iconic if hokey ’80s teen martial arts drama starring Ralph Macchio, Pat Morita and Elisabeth Shue

~ Saturday, 7pm, 5* Iconic if hokey ’80s teen martial arts drama starring Ralph Macchio, Pat Morita and Elisabeth Shue

Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom  ~ Saturday, 9pm, BBC3 Helter-skelter-ride-like second in the series of the adventure films, starring Harrison Ford, Kate Capshaw, Ke Huy Quan and Amrish Puri

~ Saturday, 9pm, BBC3 Helter-skelter-ride-like second in the series of the adventure films, starring Harrison Ford, Kate Capshaw, Ke Huy Quan and Amrish Puri

Carry On Cleo  ~ Saturday, 9pm/ Sunday, 1.30pm, ITV3 Nicely played Classical epic spoof starring Sid James, Kenneth Williams, Amanda Barrie and Jim Dale

~ Saturday, 9pm/ Sunday, 1.30pm, ITV3 Nicely played Classical epic spoof starring Sid James, Kenneth Williams, Amanda Barrie and Jim Dale

Rosemary’s Baby  ~ Saturday, 1.15am, Film4 Roman Polanski’s eerie, superior late ’60s chiller starring Mia Farrow

~ Saturday, 1.15am, Film4 Roman Polanski’s eerie, superior late ’60s chiller starring Mia Farrow

Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan  ~ Sunday, 1pm, Film4 Possibly the best of Star Trek‘s big screen outings, starring William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy

~ Sunday, 1pm, Film4 Possibly the best of Star Trek‘s big screen outings, starring William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy

Mary Poppins  ~ Sunday, 1.30pm, BBC1 The essential family musical adventure, starring Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke and those animated penguins

~ Sunday, 1.30pm, BBC1 The essential family musical adventure, starring Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke and those animated penguins

Chariots Of Fire  ~ Sunday, 6.40pm, Film4 Oscar-winning British drama focusing on the 1924 Olympics, starring Ben Cross and Ian Charleson

~ Sunday, 6.40pm, Film4 Oscar-winning British drama focusing on the 1924 Olympics, starring Ben Cross and Ian Charleson

Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade  ~ Sunday, 7pm, BBC3/ BBCHD Last of the original Indy adventures, starring Harrison Ford, Sean Connery, Denholm Elliott and Alison Doody

~ Sunday, 7pm, BBC3/ BBCHD Last of the original Indy adventures, starring Harrison Ford, Sean Connery, Denholm Elliott and Alison Doody

Ghostbusters  ~ Sunday, 7.50pm, Channel5 The classic supernatural comedy adventure blockbuster starring Bill Murray, Sigourney Weaver and Dan Aykroyd

~ Sunday, 7.50pm, Channel5 The classic supernatural comedy adventure blockbuster starring Bill Murray, Sigourney Weaver and Dan Aykroyd

United ~ Sunday, 9pm, BBC2/ BBCHD Feature-length drama about the 1958 Munich Air Disaster, in which many of Manchester United’s ‘Busby Babes’ perished, starring David Tennant

Holst ~ Sunday, 9pm, 12.20am, BBC4 Revealing documentary about the eventful life of Gustav Holst, composer of The Planets

Carry On Camping  ~ Sunday, 9pm, ITV3 The Carry On team go under canvas in perhaps their most popular movie, starring Sid James, Kenneth Williams, Barbara Windsor, Charles Hawtrey and Bernard Bresslaw

~ Sunday, 9pm, ITV3 The Carry On team go under canvas in perhaps their most popular movie, starring Sid James, Kenneth Williams, Barbara Windsor, Charles Hawtrey and Bernard Bresslaw

Elizabeth  ~ Sunday, 10pm, Channel4 Oscar-nominated, fast-paced treatment of the early years of Elizabeth I, starring Cate Blanchett, Christopher Ecclestone, Joseph Fiennes, Richard Attenborough and – yes – Eric Cantona

~ Sunday, 10pm, Channel4 Oscar-nominated, fast-paced treatment of the early years of Elizabeth I, starring Cate Blanchett, Christopher Ecclestone, Joseph Fiennes, Richard Attenborough and – yes – Eric Cantona

Indiana Jones And The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull  ~ Monday, 7.05pm, BBC3/ BBCHD Geriatric Indy returns in the latest instalment of the classic hero’s antics, starring Harrison Ford, Shia Lebeouf, Karen Allen and Cate Blanchett

~ Monday, 7.05pm, BBC3/ BBCHD Geriatric Indy returns in the latest instalment of the classic hero’s antics, starring Harrison Ford, Shia Lebeouf, Karen Allen and Cate Blanchett

Arena: George Martin ~ Monday, 9pm, BBC2 Portrait of the legendary music producer, with contributions from Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and Cilla Black

Carry On Henry  ~ Monday, 9pm, ITV3 Tudor history amusingly re-written by the Carry On team, starring Sid James, Kenneth Williams, Hattie Jacques and Barbara Windsor

~ Monday, 9pm, ITV3 Tudor history amusingly re-written by the Carry On team, starring Sid James, Kenneth Williams, Hattie Jacques and Barbara Windsor

Top Gun  ~ Monday, 9pm, Film4 Tom Cruise feels the need for speed; also starring Kelly McGillis and Val Kilmer

~ Monday, 9pm, Film4 Tom Cruise feels the need for speed; also starring Kelly McGillis and Val Kilmer

Buster  ~ Monday, 11pm, Channel 5 ’80s ‘guilty pleasure’ dramatisation of the 1963 Great Train Robbery, starring Phil Collins and Julie Walters

~ Monday, 11pm, Channel 5 ’80s ‘guilty pleasure’ dramatisation of the 1963 Great Train Robbery, starring Phil Collins and Julie Walters

The Right Stuff  ~ Monday, 11.05pm, ITV4 Acclaimed epic focusing on the early years of America’s astronaut programme, starring Ed Harris, Scott Glenn and Dennis Quaid

~ Monday, 11.05pm, ITV4 Acclaimed epic focusing on the early years of America’s astronaut programme, starring Ed Harris, Scott Glenn and Dennis Quaid

A Hard Day’s Night  ~ Monday, 11.15pm, BBC2 The Beatles’ fast, furious and fantastic first foray in film

~ Monday, 11.15pm, BBC2 The Beatles’ fast, furious and fantastic first foray in film

Snowdon And Margaret: Inside A Royal Marriage ~ Monday, 12.25am, More4 Documentary about the tumultuous marriage of Princess Margaret and Anthony Armstrong-Jones

Slickly done: ‘White Rabbit In Wonderland’ – one of Grace Slick’s (writer and singer of Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit) recent interpretations of Lewis Carroll’s characters through fine art

You know, for me, there can be few creatures that in this most spring-like of months, yes, springs to mind as much as the loveable, oh-so cuddly rabbit. Full of vitality, fun and, erm, reproductive instincts, it’s surely this season’s archetypal animal; whether it’s hopping to and fro here and there, embodying the spirit of Easter in bunny-form like old Santa does for Crimbo or hurrying along, inspecting a pocket-watch and declaring it’s ‘late, late, late!’

Ah, not quite with me on that last one, eh? Well, forgive me, because doubtless I was minded to make that reference to the eponymous White Rabbit owing to the fact that Alice In Wonderland really is something of a must with me. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not the only one; but for the same token, the idea of sitting down at a table with The Mad Hatter certainly isn’t everyone’s cup of tea (after all, that very exercise may end up going on forever).

But why? Why do some find Alice & co. eminently and forever fascinating, while others could take or leave or even do without them? Well, I guess it’s fair to say that all things Alice, by their very nature, are surreal, psychedelic and not a little nonsensical. Some just can’t get their heads around it all; to enter yourself into Alice’s world almost feels as if you’re off your head (rather than off with your head – an important distinction to make that). Yet, speaking for myself, that may be exactly the whole thing’s appeal.

It all started way back in 1862. One July afternoon, the Reverend Charles Dodgson was on the River Thames, near Oxford, rowing a boat that contained three sisters, Lorina Liddell, Edith Liddell and the middle sibling, eight-year-old Alice Liddell – the daughters of Dodgson’s friend Henry Lidell, Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University and Dean of Christ Church College. During the boat journey, Dodgson told the sisters a story about a girl named Alice and her fantastical adventures. Having enjoyed the story, the real Alice told Dodgson to write it down so she might read it. In time, Dodgson expanded on it and produced a manuscript, Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, which he presented to Alice in November 1864 as a Christmas present.

The master and his muse: Charles Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) posing as if at work (left) and Alice Liddell posing as a beggar maid for a photo taken by Dodgson himself in 1858 (right)

However, he’d also been working on the manuscript with a view to getting it actually published and Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland was finally published in 1865. It was written under the pseudonym of ‘Lewis Carroll’ and featured 42 wood-engraved illustrations produced by John Tenniel. Almost immediately, the book was a success, its entire print run selling out quickly; however, it became a true sensation when Dodgson published its sequel Alice Through The Looking Glass, And What Alice Found There in 1871. From that point on, Alice’s two adventures sold like hot (tea party) cakes. Apparently great early fans included both Queen Victoria and a young Oscar Wilde, while the esteemed late Victorian novelist and historian Sir Walter Besant wrote: “[Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland is] a book of that extremely rare kind which will belong to all the generations to come until the language becomes obsolete”. He may well be right.

All most impressive, you might say, but children’s books of more or less the same era such as Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind In The Willows and the most successful of Beatrix Potter’s tales can also boast enormous popularity over the same length of time. What sets Alice apart? Well, frankly, it’s the very thing about it that proves a stumbling block for many – its very surrealism or, if you prefer, it’s nonsensical nature. And therein lies the rub; when one looks a little closer things become clear and Alice becomes far less a bundle full of nonsense down a rabbit hole.

Of course, on one level, that’s exactly what both Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and Alice Through The Looking Glass are: deliberately surrealistic tales about a little girl’s adventures – or, rather, almost disconnected episodes – in her sleep, featuring crazy characters (many of them talking animals) whom she meets in sometimes light, other times dark, dreamy situations. No wonder then the books went down such a storm with kids. However, on another, yes, deeper level, both the books feature symbolism. And clever-clever it is too.

Tenniel’s trio: Alice (l), The Mad Hatter (m) and The White Rabbit (r) as interpreted by illustrator John Tenniel in the original published version of Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland

First of all, take a look at the setting of both stories. Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland starts outdoors in May (a warm month), concerns itself with many changes in size and includes playing cards; Alice Through The Looking Glass opens indoors in November (a cold month), concerns itself with changes in time and spatial directions and includes chess. The latter mirrors the first or, if you will, looks at the former ‘through a looking glass’.

In fact, Alice’s world is crammed full of symbolism. Obvioulsy the character of Alice herself is influenced by Alice Lidell (although Tenniel’s illustration of her, all blonde and blue skirted – the foundation of all her subsequent visual interpretations – bears little resemblance to the real Alice). The Mad Hatter most likely references Theophilus Carter, an Oxford art dealer and eccentric inventor who showed off his alarm clock/ bed-combination at The Great Exhibition in 1851 and had a habit of standing in the door of his shop wearing a top hat. It’s believed Dodgson suggested Tenniel draw Hatter to look like Carter.

In Chapter Three of the first book (‘A Caucus Race and a Long Tale‘), the Oxford boating party are all present – clearly Alice is there, while Dodgson himself is the Dodo (as he had a stutter, he’d often introduce himself as ‘Dodo-Dodgson’), Lorina Lidell is The Lory and Edith Lidell is The Eaglet. The party also included Dodgson’s friend Canon Duckworth, who, of course, is The Duck. Meanwhile, The Queen of Hearts almost definitely alludes to Queen Victoria (owing to her grumpy, impatient personality) and it’s thought that Bill the Lizard may be a play on the name of the twice British Prime Minister of the era, Benjamin Disraeli. Also, the ‘old conger eel’, ‘a drawling master’, that The Mock Turtle tells Alice of is undoubtedly the famous art critic John Ruskin, who came once a week to teach the Lidell sisters drawing, sketching, and painting in oils (“he came once a week to teach… Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils”).

Crazy hat and groovy cat: The Mad Hatter’s tea party (l) and The Cheshire Cat (r) in Disney’s take on Carroll for kids – the movie would be taken on by a different crowd in years to come

Aside from symbolism, Dodgson also has fun with foreign languages (French and Latin puns appear), while more overtly he plays around with logic throughout the books. An academic, the author taught mathematical logic at Christ Church College and it’s believed – especially by Keith Devlin in a March 2010 article of The Mathematical Society of America’s journal – that he in fact used Alice’s interactions with many of the characters as satirical sideswipes at then radical new theories of late 19th Century mathematics, some of them deep abstractions of logical concepts. A good example is the episode of The Cheshire Cat, appearing and disappearing and sometimes leaving his grin behind as he does so. At the time, new thinking in the world of maths was considering the possibility of numbers themselves not being dependent on an object, so numbers (the grin) could exist even when their object (the cat) does not.

All the same, much of this has naturally been lost on readers of Alice’s adventures down through the years; as far as they’re concerned, the dreamy nonsense they contain is just that, not allusions to people its creator knew or plays on maths theories and language. And not that any of that has mattered anyway. Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland has now been published in 125 different languages and, to this day, never been out of print. And, whether they needed it or not, both of Dodgson’s books received a boost in post-war popularity when in 1951 they were given the Disney treatment. Fair dos, the tales had been adapted for both stage and screen many times already, but Uncle Walt’s lavish big screen animated interpretation has surely managed – and was always likely to – checkmate all the others.

In actual fact, before settling on the Snow White fairytale as a subject, Disney had had Alice and chums in mind for his studio’s first feature-length film way back in the 1930s. He’d envisaged it as a live-action/ animated crossover (in the manner of, say, 1964’s Mary Poppins) and had even screentested heavyweight Hollywood star Mary Pickford for the lead role – even though she would have been around 40-years-old at the time. Unsurprisingly, this crack at adapting Carroll’s work didn’t come off. When the film was eventually made, Disney took the decision to combine both Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and Alice Through The Looking Glass into one movie, simply called Alice In Wonderland. (Confusingly, both Dodgson’s first book and the first book and second book together had been – and continue to be – sold under that title).

Disney also decided to preserve the ethos of the books, rather than adapt them as closely as possible, preferring to allow the cartoon visuals and songs (as many as 30 – count ’em) tell the story. The result didn’t exactly enthrall the critics – perhaps unsurprisingly those of a British persuasion were the most sniffy. Yet, while Walt’s stab at Alice is clearly, well, ‘Disneyfied’, what with its bold coloured and lush animation, it’s certainly faithful in retaining the fantasy, whimsy and many of the characters of the world Dodgson created. And while the animation hasn’t the stark, almost comically alien quality of Tenniel’s illustrations, it truly is luscious and, thus, beautiful in its way.

Right or wrong, the critics weren’t the only ones not to be bewitched by the film, cinema-goers weren’t entirely either; unlike Disney’s cartoon classics of the ’40s and those to come later in the ’50s, Alice In Wonderland was far from a huge hit on first release. However, in the following decade, an unpredictable, unexpected thing happened (rather fitting for Alice you might say), yes, the Disney adaptation found an audience – and probably from the least likely source.

By now, it was, of course, the mid- to late ’60s, when drug experimentation and self-discovery were increasingly significant tenets of youth culture and, thus, the swirling, mind-bending, colourful confusion of psychedelia and surrealism was very much in vogue. This ensured that the movie, despite the resistance of Disney and his company, was (like 1941’s Fantasia) now considered a ‘head film’ and being shown in college towns across America.

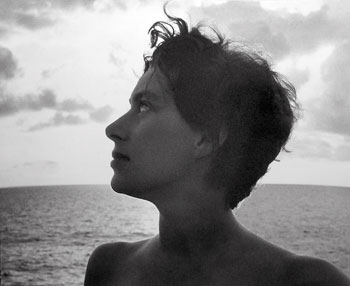

California dreamin’: the album cover to Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow album (r); ‘Scout’ a self-portrait by Grace Slick from a 1960s photo in which she wears a scout jacket (l)

Mind you, Disney’s version of Alice wasn’t the first animated flick to be looked on as a ‘head film’. Its rediscovery was arguably a ride on a bandgwagon, as it followed in the wake of another’s release – The Beatles-‘starring’ cartoon classic, Yellow Submarine (1968). Yet, ironically, or perhaps logically, one could confidently say that it was the very Lewis Carroll-inspired facets of The Beatles’ work that proved the cue for director George Dunning to make his animated ode to their music quite so fantastical, vibrant, crazy, colourful – quite so, in a word, psychedelic. The Fabs’ appreciation of Dodgson’s work (the mixed-up fantasy world with its assortment of characters; the constant word-play etc) is widely known, especially that of John Lennon, and, as such, its influence is noted in much of their mid- to late ’60s output.

The most obvious exponent, of course, is the 1967 Lennon-penned I Am The Walrus, the B-side to the UK and US #1 single Magical Mystery Tour. The title, in fact, itself a line in the song, directly references The Walrus character in ‘The Walrus And The Carpenter’ poem that appears in Alice Through the Looking Glass. Lennon later said that he had mis-read the poem, having always assumed The Walrus was the ‘good guy’ of the poem and The Carpenter the ‘bad guy’, when it’s actually the other way around. Looking deeper, though, one can identify Alice inspiration in several of the songs on the seminal 1967 Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album (Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds is overspilling with it), while the likes of Penny Lane, Fool On The Hill (from the 1967 Magical Mystery Tour album), Happiness Is A Warm Gun, Piggies (both from 1968’s White album), Octopus’s Garden, Mean Mr Mustard and Polythene Pam (each from 1969’s Abbey Road) could all be said to be lyrically and stylistically Carroll-esque.

And, when you get down to it, it’s really no surprise the young and the hip of the ’60s (whether artists or their followers) found Dodgson’s Alice adventures so psychedelic, surreal and, well, druggy. I mean, not only do they contain anthropomorphic characters ranging from the seemingly over-stimulated (Hatter) to the seemingly sleepily stoned (The Dormouse) and from the paranoid (The White Rabbit) to the actually visually ambiguous (The Cheshire Cat), one of them is even smoking a hookah-pipe (the always chilled out Caterpillar). Quite frankly, all of them seem to be tripping.

Familiar (furry) faces: Alice re-done as a family film in 1972 with Peter Sellers as The March Hare (l), Dudley Moore as The Dormouse (m) and Michael Crawford as The White Rabbit (r)

Associations of Alice with drug culture were to be seen everywhere at the time. While the ‘Disneyfied’ image of The Cheshire Cat was a constant on LSD blotters, Alice herself actually tripping was alluded to in a black-and-white, feature-length Alice In Wonderland adaptation, directed by former Beyond The Fringe member Jonathan Miller and broadcast by the BBC on December 28 1966 (see video above). Typical family fare for Christmas this was not, as the ‘Eat me’/ ‘Drink me’ sequence in which Alice grows larger and smaller was treated as if her activities were inducing her into a drugged state. No question, this version is a dark take on Dodgson’s work; Miller decided to film the animal characters as human characters, believing the story to be a cypher for a girl’s fears about the grown-up world around her: “Once you take the animal heads off, you begin to see what it’s all about. A small child, surrounded by hurrying, worried people, thinking ‘Is that what being grown-up is like?”.

However, the ultimate 1960s interpretation of Alice has to be, of course, the Jefferson Airplane single White Rabbit (see video at bottom). An all-time rock (or, to be specific, psychedelic rock) classic, the single was released in 1967, reached a high of #8 in the US charts and featured on the seminal album Surrealistic Pillow. Written by singer Grace Slick, who had recently joined San Francisco-hailing Jefferson Airplane from fellow Frisco band The Great Society, the song, despite its clever enigmatic lyrics that ensured it got past radio censors, pretty explicitly draws comparison to imagery from Dodgson’s Wonderland with the hallucinatory effects of drugs such as LSD and ‘magic mushrooms’. The lyrics reference growing larger and smaller, chess, talking backwards, Alice herself, The White Rabbit naturally, The Dormouse and The Red Queen (from Through The Looking Glass; mistaken for Adventures In Wonderland‘s The Queen of Hearts). Rather like Ravel’s Boléro, the tune features a rising crescendo, enhancing its effect, and is surely, unquestionably a musical masterpiece.

Curiously (and, you might say, curiouser-ly), in the years since that song’s release, the inimitable Ms Slick has never really been able to kick the Carroll habit. Although she’s long since severed ties with Jefferson Airplane and its off-shoot band (Jefferson) Starship, she still uses Wonderland imagery for inspiration as part of her recent work as a successful artist. Previously a major mover-and-shaker of the ’60s California rock scene (she was a close friend of Janis Joplin), in her time Slick experienced many ups – literally and figuratively – and downs, including alcoholism. Unsurprisingly then, many of her art pieces tend to look back and refer to the scene she was once at the heart of and some of these also unapologetically mix in Alice references. A fine example is, indeed, the ‘White Rabbit In Wonderland’ painting to be seen at the top of this article. In it, Slick has substituted ’60s counter-culture figures for some of Carroll’s characters – Timothy Leary is The Mad Hatter, spiritual teacher Ram Dass is The Caterpillar and, for reasons only she will know, a raccoon is The Cheshire Cat and a lab rat The Dormouse. She always was a one-off that Grace.

Pills, thrills and Hoggle-aches: interpretations of and elements borrowed from Carroll have abounded onscreen in recent years – cult classic Labyrinth (l) and sci-fi smash The Matrix (r)

Inspiration by, adaptation of and reference to Alice’s adventures didn’t end in the ’60s, though. Like it or not, they’ve been a veritable constant of modern culture. As soon as the early ’70s, Dodgson’s books were once again mined as the source for a major family film in the shape of Alice In Wonderland (1972). British-made, thoroughly charming and fondly recalled, this movie musical boasts future Bond Girl Fiona Fullerton as the heroine (once more blonde and in a blue dress) and the cream of British acting talent, such as Ralph Richardson, Robert Helpmann, Michael Hordern and Spike Milligan, among others. A very different effort followed five years later, with off-kilter filmmaker Terry Gilliam’s debut flick Jabberwocky, which features the Jabberwock monster from Alice Through The Looking Glass, but no other Wonderland inhabitants.

No Carroll characters at all appear in the forever popular Labyrinth (1986); however, what with a girl on a journey through a fantasy world, weird creatures including goblins, tiny caterpillars and ogres as armoured guard, as well as a playful if moody monarch as a major antagonist with too much time on his hands (yes, all 13 hours of it), the Alice inspiration is pretty clear. It also stars David Bowie and features Muppet-like creatures created by Jim Henson, which just makes it cool. Another film released at this time, Dreamchild (1985), directly refers to Dodgson and Alice Lidell and again utilised Jim Henson’s creativity – this time with rather grotesque recreations of Wonderland inhabitants.

And the Carroll card has continued to be played into the new millennium, of course. Lest we forget, the hugely successful and undeniably iconic The Matrix (1999) smartly references Alice (‘follow the white rabbit’; ‘the red and blue pills’ etc), while just last year Disney gave the whole merry-go-round another go by employing the services of Tim Burton to direct the Johnny Depp-headlining Alice In Wonderland, in which Alice, on the cusp of adulthood, returns to the world she once knew to defeat The Red Queen and the Jabberwock once and for all. Undoubtedly a loose ‘adaptation’, Burton nonetheless remained faithful to the books’ essence and, in doing so, scored the third biggest global box-office hit of 2010.

In the end then, there is, well, no end to Alice In Wonderland. Like, say, Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, Dodgson’s two books originally written for children have been a source of cultural indulgence through both themselves and the other artistic ventures they’ve inspired for decade after decade. They’ve provided innocent entertainment, intellectual analysis, sheer befuddlement and hipster enhancement for almost every different demographic of the Western world you could care to mention. While there’s clearly so much depth and breadth to burrow into in the Alice tales, there’s also a universality about them too; an appeal that simply anyone, whether they be a Mad Hatter, a Tweedledee or Tweedledum or a Queen of Hearts, gets. In the end, all of us have strange dreams, many of us like the idea of retreating into a fantasy world and some of us will always think of The White Rabbit when we see a fluffy bunny hopping to and fro here and there. As Dodgson would perhaps have it, it simply comes down to logic really.

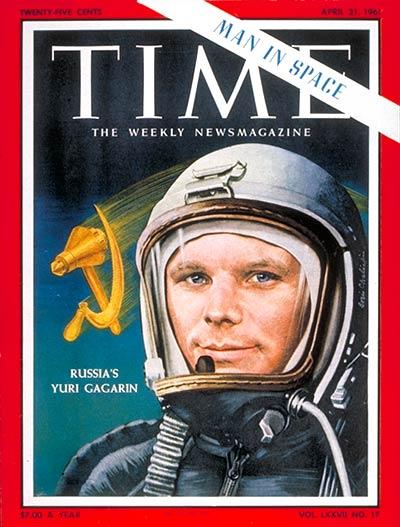

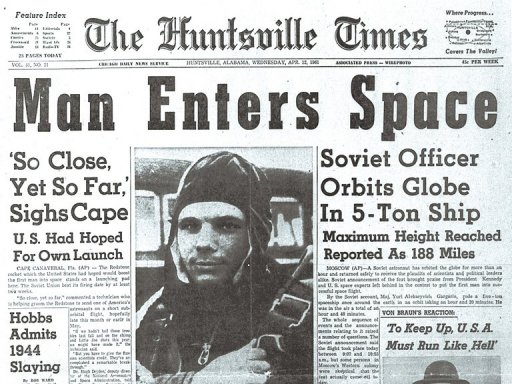

Starman: Yuri Gagarin, Mother Russia and the world’s first space-traveller-hero – after his exploits he did indeed like to come and meet us (in many crowds) because he blew our minds

Back in the day, as far as the United States was concerned and much to its chagrin, those pesky Ruskies managed to beat them to several firsts. Of the two, at the end of WWII the USSR was the first to enter Berlin, it was the first to launch a satellite that left the earth and, yes, it was the first to hold the Olympics (Moscow 1980 beat the Los Angeles event by just four short years). Mind you, what perhaps really stuck in the Yanks’ throats and, thus, so publicly fuelled the flames of the Cold War, is the fact that, 50 years ago this very day, the Soviet Union became the first of the two to put an actual man into space.

That man, of course, was Yuri Gagarin. A name that surely has so fundamentally gone down in the annals of history it’s as instantly recognisable as those of Alexander the Great, Bill Shakespeare and Casanova. Oh, and Neil Armstrong, of course. For, let’s not kid ourselves, Gagarin’s achievement (and that of his important collaborators) is among the most extraordinary the human race has ever pulled off. In 1903, the Wright Brothers made the first powered human air-flight; just 58 years later, thanks to a heady mix of scientific and mathematical genius, heavy industry, a nuclear arms race and global and ideological rivalry, Gagarin became the first human being to be powered beyond the Earth itself.