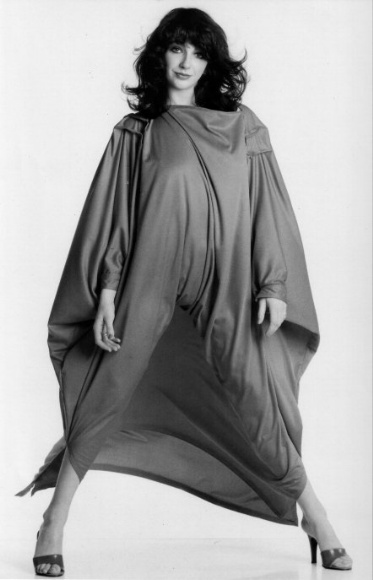

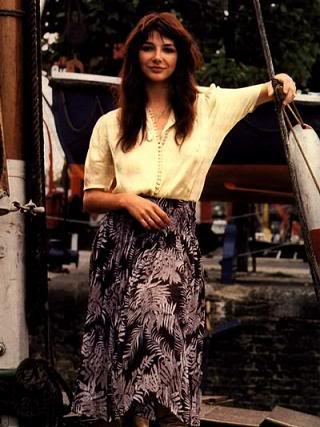

Kate Bush: Wow

Talent…

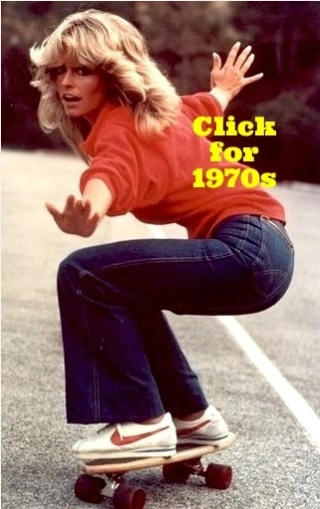

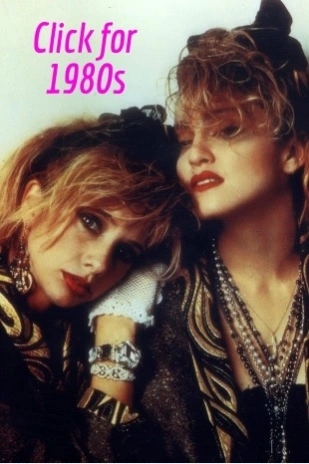

… These are the lovely ladies and gorgeous girls of eras gone by whose beauty, ability, electricity and all-round x-appeal deserve celebration and – ahem – salivation here at George’s Journal…

~~~

Beautiful, brilliant, original, enigmatic, reclusive and a wee bit weird, there’d never been anyone quite like Kate Bush, and there probably never will be again. She set pop music on its head and sent mensfolk’s pulses racing. Her eclectic and sophisticated sounds were huge in both the ’70s and ’80s and she didn’t look half bad along with it – and for these reasons she’s an unquestionable shoe-in for the Talent corner of this blog.

~~~

Profile

Name: Catherine ‘Kate’ Bush

Nationality: English

Profession: Musician

Born: 30 July 1958, Bexleyheath, Kent

Height: 5ft 3in

Known for: Producing and performing arty yet mainstream music predominantly in the ’70s and ’80s, including the albums The Kick Inside (1978), Lionheart (1978) and the hugely acclaimed Hounds Of Love (1985), as well as the hit singles Wuthering Heights (1978), The Man With The Child In His Eyes (1978), Babooshka (1980), Running Up That Hill (1985), Cloudbursting (1985) and Don’t Give Up (1986) – a duet with Peter Gabriel.

Strange but true: Sound engineers constructed for her an early headset mic out of a coathanger and a radio microphone, as she wished to sing and dance at the same time during her six-week-long The Tour Of Life tour in 1979, in which she went through a total of 17 costume changes for each show.

Peak of fitness: Alternatively playing with a double bass and dressed in Amazonian warrior-like get-up in the strange and not a little suggestive Babooshka video

~~~

CLICK on images for full-size

Playlist: Listen, my friends! ~ September

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and enjoy…

CLICK on the song titles to hear them

~~~

The Moody Blues ~ Om

Steppenwolf ~ Magic Carpet Ride

Simon And Garfunkel ~ El Condor Pasa (If I Could)

John Lennon ~ God

Badfinger ~ Day After Day

The Who ~ Sparks

Slade ~ How Does It Feel?

David Bowie ~ Speed Of Life

Billy Joel ~ Scenes From An Italian Restaurant

Earth, Wind & Fire ~ September

Journey ~ Wheel In The Sky

Roxy Music ~ Same Old Scene

Patti Labelle ~ Stir It Up

Nowhere Man?: Lennon Naked (2010) ~ Review

Directed by: Edmund Coulthard

Starring: Christopher Eccleston, Christopher Fairbank, Naoko Mori, Claudie Blakley, Rory Kinnear, Michael Colgan, Adrian Bower, Andrew Scott

Screenplay by: Robert Jones

UK; 82 minutes; Colour/ b&w; Certificate: 15

~~~

What with the ever increasing deluge of dreck clogging up our telly screens these days, I must admit the BBC4 TV channel has become something of a refuge for me. With its mixture of arts, historical and science programmes, as well as smart original drama, it may just be the best channel around (sad to report, though, it’s only available in the UK and Northern Ireland, you non-home-nations people out there).

So, it was with curiosity and expectation I came upon a repeat the other night of this fictional retelling of John Lennon’s life between the years of 1967 and ’71. This period of his life is, for sure, a big canvas to cover requiring both broad and subtle brushstrokes, but if any TV drama could pull it off, surely it would be one comissioned by BBC4, wouldn’t it?

But did it pull it off? Well, yes and no. For me, what Lennon Naked gets both right and wrong is its attention to, or rather emphasis on, detail – the angel and the devil’s in the detail, if you will. So, first up, the good. The painstaking work that has gone into making the drama feel like it’s right out of the late ’60s and early ’70s is all there – period detail including the fashions, furnishings, vehicles and streetscapes is all present and correct (you really feel like you’re in Lennon’s world, swaggering hippiedom collides with the straight-laced stockbroker London suburbs, where he set up home, or rather mansion, with wife Cynthia and son Julian).

Add to that the casting, Rory Kinnear is pretty much spot on with his restrained, softly spoken Brian Epstein (his early, ’64-set scenes with Lennon nattily filmed in monochrome, reminiscent of A Hard Day’s Night), while Claudie Blakley delivers a nicely balanced Cynthia, and Michael Colgan and Adrian Bower convince in believable interpretations of Beatles alumni Derek Taylor and Pete Shotton, respectively.

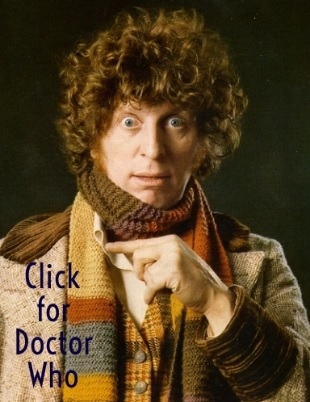

Moreover, there’s absolutely no doubt that the esteemed acting talent that is Eccleston (former Doctor Who and star of the outstanding Our Friends In The North – the last great British serial drama) relishes getting his teeth stuck into bringing Lennon back to life, warts and all. His performance is at its best when recreating John’s sardonic demeanour, full of customary caustic wit (thanks to writer Robert Jones giving him Lennon-esque dialogue that sounds true to the ear – Fan on the street: “Kiss me, John!”/ Lennon (indicating Brian Epstein): “Kiss ‘im – ‘e’s never been kissed by womankind… or unkind”). The accent too isn’t bad, even if the actor’s own Salford twinge comes out through the scouse once or twice. And, naturally, Eccleston does very well in peeling back the layers of Lennon’s glass onion – bringing out the existential, drug-addled darkness at the heart of the man’s soul that much of the music he produced during this era (especially in his solo material) suggested or even spelt out was there.

However, at the same time, I’d argue that it’s here that this film gets it wrong. And, to be fair, it’s not necessarily Eccleston’s fault. He’s an actor who’s outstanding in expressing angst, it’s just a pity that the production seems intent in pretty much only expressing this. The ’67-’71 period in Lennon’s life was turbulent, of course, there’s a lot of gloom there to draw on: troubled reconnection with his father Freddie (a fine Christopher Fairclough) – around which the drama pivots, leaving his wife and son, drug addiction, ‘primal scream’ therapy and, far from least of all, the break-up of The Beatles. And the drama revels in it all, as Lennon escapes reality in a transcedental-like dip in his swimming pool, lies strung-out in a dingy bathroom’s bath, gets busted for drugs and (apparently) takes the psychological blame for the Fabs’ break-up. Yet, all that surely was only part of the story, wasn’t it?

Sure, Lennon’s meeting and burgeoning relationship with Yoko is shown – indeed, much is given over to it – but it hardly presents this side of the story as the beautiful discovery, nay saving grace, it obviously was for the protagonist. Instead, it goes down the easy route of public perception of the time – the tone of their scenes is together more awkward and freakish than fitting and blissful. Yes, Jonh’s finding Yoko precipitated his divorce from Cynthia (and there’s a strong scene devoted to this), but it was also a huge step for Lennon himself, even if he went through heroin addiction at the same time.

For me, then, this approach is somewhat cynical, let alone unoriginal really, and casts Lennon in the tragic hero role (especially with its emphasis on abandonment by his parents); conveniently completing his story, as it does, at the point when he and Yoko left Britain for New York where their happy years together began and John probably felt at home for the first time.

Fair enough then, this flick doesn’t get all schmaltzy over Imagine and the such like, but with a little more imagination methinks it could have presented its subject in a fairer, more balanced manner than merely the heavily toubled, unpleasant and far from Fab chap it offers us up instead.

For a brief time, you can watch Lennon Naked on the BBC iplayer (UK and Northern Ireland only) here, or it can be purchased here.

Tartan titan: Happy 80th birthday, Sean Connery

Muscle beach: Sean Connery showing he’s still got it at the Cannes Film Festival in 1999

He’s consistently considered the best Bond, he’s clearly one of Britain’s greatest films stars and he’d be the only possible candidate to become (the latest) King of Scotland should his home country ever become independent… yes, today, my friends, the redoubtable, indefatigable, undeniable Sean Connery is 80 years young.

And, really, when you think about it, it’s no surprise this Scottish institution has reached that very milestone – he’s been an international insitution for longer than many of us have been alive. It was way back in 1962 when Connery debuted as 007 in Dr No, the opening adventure of the Eon film series, and, of course, he went on to make another five of them, From Russia With Love (1963), Goldfinger (1964), Thunderball (1965), You Only Live Twice (1967) and Diamonds Are Forever (1971).

Bond put him on the map for sure, although he had something of a career before that role came along, taking lead duties (and singing) in Disney musical Darby O’Gill And The Little People (1961) and a supporting role (not singing) opposite Lana Turner in melodrama Another Time, Another Place (1958). Indeed, while making the latter film Turner’s gangster boyfriend Johnny Stompanato became jealous of Connery spending so much time with his much better half, so pointed a gun at him – his response was to grab the gun, twist Stompanto’s wrist and force him to flee. It wasn’t the first time the surly Scot’s anger and more violent side would surface. He would later publicly state that, in the right circumstances, he believed it acceptable to hit women and, since their marriage, his first wife has accused him of physical abuse. More Irn Bruiser than squeaky clean, you might say.

“Unlike many tattoos, his [Connery’s] were not frivolous – his tattoos reflect two of his lifelong commitments: his family and Scotland … One tattoo is a tribute to his parents and reads ‘Mum and Dad’, and the other is self explanatory, ‘Scotland Forever’.” ~ The Official Website Of Sir Sean Connery

Conners then has had a controversial time of it over the years and, by all accounts, didn’t particularly enjoy his time in Bondage. Becoming annoyed by the focus on gadgets and spectacle over more realistic espionage, he tired of making the spy films (mid-’60s ‘Bondmania’ and the intense media attention it brought him far from helped either). By the early ’70s, he had to be lured back with a paycheck of $1million (at that time, an enormous front-end deal for a film star) and contributions to his newly set-up Scottish education fund, in order to make his final appearance. He did however play 007 one more time in the ‘unofficial’ film, 1983’s Never Say Never Again. Like all the others, it too was a mega-hit.

Post-Bond, that wasn’t the only unusual choice he took in his career either. There was a cowboy opposite Bridget Bardo in Shalako (1968), an apocalyptic leader in Zardoz (1974), a space sheriff in Outland (1981), an Egyptian-cum-Spanish eternal warrior in Highlander (1986) and an Amazon-based doctor with a long ponytail in Medicine Man (1992).

Yet alongside the misses, there’s also been hits of real quality – he was directed by Hitchcock in Marnie (1964), directed by John Huston and starred opposite Michael Caine in The Man Who Would Be King (1975), won a BAFTA Award for his role as a monk detective in The Name Of The Rose (1986), played a Russian submarine captain in The Hunt For Red October (1990), romanced Audrey Hepburn in Robin And Marian (1976) and Michelle Pfeiffer in The Russia House (1990) and won every award under the sun (including an Oscar) for a bombastic, hard-hitting turn in Brian De Palma’s classy and stylish The Untouchables (1987). All that and, of course, he was sought out by Steven Spielberg and George Lucas to play Indy’s dad (thanks to the logic that only James Bond could play that role) in Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989).

Nowadays Connery is retired from acting – citing Hollywood is run by ‘idiots’ – and seems to spend much of his time backing Scottish nationalist projects and calling for the country’s independence from the UK. And, despite this political stance, like the man who replaced him as 007, he was knighted by the Queen herself in July 2000.

All in all then, not bad for a former milkman, lorry driver and coffin polisher from Edinburgh. Indeed, what with his career resurgence in the ’80s, he was even voted ‘Sexiest Man Alive’ at the age of 59 – and who would argue with that? What man would argue with all the world’s women, after all?

So, on this most distinguished of days in his life, let’s raise a glass of scotch to the man, the legend, the Scotsman forever, Sir Sean Connery. The man who would be king? Nah, more like the man who’s always been king.

~~~

The ten greatest Connery moments

(CLICK on the links!)

10. Highlander (1986) ~ ‘Greetings’

9. A Bridge Too Far (1977) ~ ‘Do you think they know something we don’t?’

8. Robin and Marian (1976) ~ The showdown

7. Time Bandits (1981) ~ ‘It’s evil!’

6. Goldfinger (1964) ~ ‘Man talk’

5. Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989) ~ ‘I suddenly remembered my Charlemagne’

4. The Man Who Would Be King (1975) ~ ‘Can you forgive me?’

3. The Untouchables (1987) ~ ‘What are you prepared to do?’

2. From Russia With Love (1963) ~ ‘Old man’

1. Dr No (1962) ~ ‘Bond, James Bond’

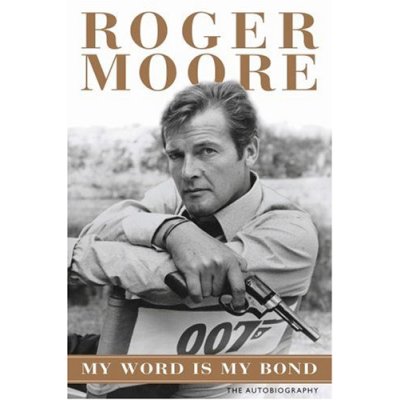

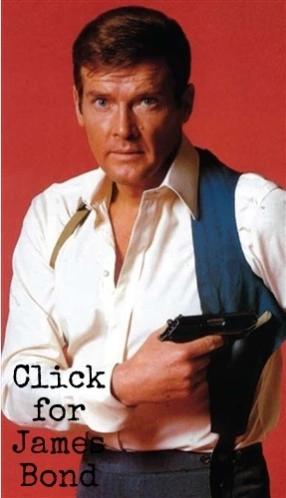

Review: My Word Is My Bond – The Autobiography ~ Roger Moore

Author: Roger Moore, with Gareth Owen

Year: 2008

Publisher: Michael O’Mara Books (UK)/ HarperCollins (US)

ISBN: 9781843173182 (UK)/ 0061673889 (US)

~~~

James Bond. Simon Templar. Lord Brett Sinclair. Tongue-in-cheek, old-school, British screen institution. Everybody knows Sir Rog? Or do they?

Well, admittedly, reading My Word Is My Bond – The Autobiography is unlikely to change your perception or rough view of the legendary actor much, but it will certainly give you a broader and deeper appreciation of his career and life. Written and published to coincide with Moore’s 80th birthday, it’s heavy on detail – as every decent biography should be – but also showcases Sir Rog’s trademark and effortless wit, wisdom and irresistibly saucy sense of humour. And, if you’re an admirer of the man (surely most likely if you’re considering reading the book), then that’s definitely a good thing.

Be sure too that, chronicling his life from humble beginnings in Stockwell, South London, and as a budding theatre actor, then the years as a contract player with MGM and Warners, through TV work on Ivanhoe, Maverick, The Saint and The Persuaders!, and finally to Bond and beyond, there’s many a golden anecdote to be savoured between its pages.

Take, for example, ex-Marine Lee Marvin – co-star on adventure film Shout At The Devil – putting a stuntman out of work just to prove he could still swim through a raging sea, and Christopher Lee singing opera in Italian before bed each night while staying in tiny shacks on an uninhabited Thai island during the filming of The Man With The Golden Gun. Not forgetting Stewart Granger’s (Sir Rog’s one-time idol) reaction to bus-waiting folk bursting into laughter as the former’s suitcase breaks open on the street – another unquestionably candid and bawdy highlight.

However, if you’re looking for warts-and-all exposés behind Moore’s time in Bondage or other intriguing Hollywood projects he was involved in, then this read won’t be for you. For instance, the controversy generated by the filming of 1974’s Gold in apartheid-era South Africa is glossed over in favour of recollections of how a difficult production was pulled off. Plus, as admitted from the off it won’t be, the autobiography has little interest in bad-mouthing people of whom Moore hasn’t fond memories, and what with his reportedly tempestuous marriage with singer Dorothy Squires, there must be a few.

Yet, given the author’s easy-going, playful and friendly personality, it’s a good decision – the book would surely be the worst for any out-of-character bile. Instead, the tone is cosily conversational and jovially informative, the subject often humbly suggesting he’s a ‘ponce’ for taking on projects for money rather than artistic merit and doubting his own acting ability – both of which underline this is a Hollywood legend refreshingly free of ego. And that’s in spite of constant name-dropping, which comes across as disarmingly interesting rather than narcissistic; one instinctively believes Moore’s claims to have been friends with a good number of yesteryear’s steller screen names. Why wouldn’t he have been?

Indeed, Sir Rog has, of course, been a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador for the past 20 years and, noting that as an elderly man he still undertakes this globe-trotting role with gusto, it’s clear he’s a genuinely kind-hearted chap who, having years ago landed on his feet with a successful acting career and the privileged life that brought him, is only too pleased – if you will – ‘to give something back’. Indeed, concerning this era of his life as it does, the last leg of the book’s journey makes for quite the poignant and thoughtful insight.

One revealing tidbit is that it was Audrey Hepburn who persuaded Sir Rog to become involved in UNICEF, nagging him to speak at an event in May 1991, and following her untimely death in 1993, he felt he had no alternative than to carry on her work by essentially taking over her role with the organisation. Clearly then, this is admirable stuff and, clearly, like practically any man would, Sir Rog found it impossible to turn down a request from the angelic Audrey.

So, if you fancy a little enlightenment on the worlds of UK and US television and filmmaking from the ’50s through to the ’80s, sprinkled with genuine stardust, from one of the great entertainers, then My Word Is My Bond may be right up your street. My word, I’d go as far as vouching my Martini on it.

My Word Is My Bond – The Autobiography is available to buy here.

Playlist: Listen, my summer friends! ~ August

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

So, not to tempt fate and jinx it so it downpours every day in August (it couldn’t, could it?), this month – and this month only – I’ve spoiled you, folks, because, yup, here’s a super-dooper summer special of a playlist. Oh yes!

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and knock your bucket and spade together to the tunes…

Click on the song titles to hear them

~~~

Martha And The Vandellas ~ Dancing In The Street

The Lovin’ Spoonful ~ Summer In The City

The Who ~ Summertime Blues

Love ~ Bummer In The Summer

Janis Joplin ~ Summertime

Cream ~ Sunshine Of Your Love

The Fifth Dimension ~ Aquarius/ Let The Sunshine In

The Isley Brothers ~ Summer Breeze

Starland Vocal Band ~ Afternoon Delight

The Style Council ~ Long Hot Summer

Glenn Frey ~ The Heat Is On

The Stranglers ~ Always The Sun

The Beach Boys ~ Kokomo

The global jukebox: Live Aid ~ July 13 1985

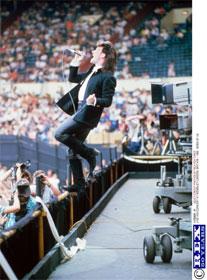

Freddie and the dreamers: Queen’s frontman leads a capacity Wembley Stadium in perhaps the most memorable – and magical – set at the extraordinary, unforgettable Live Aid event

All decades have defining moments. For instance, the ’50s have the wedding of Prince Rainier of Monaco and Grace Kelly, the ’60s have Jimi Hendrix playing the Star Spangled Banner at Woodstock, and the ’70s have the Israeli athletes’ kidnap at the Munich Olympics. As far as the ’80s go, one of its defining moments, unquestionably, has to be Live Aid – an event that, of course, celebrated its 25th anniversary a couple of weeks ago.

Live Aid was momentous, miraculous, inexplicable and unforgettable. It changed the music industry and charity-giving forever and brought the world together in a way that had never quite happened before. And, when you get down to it, it was all Michael Buerk’s fault.

One evening in the autumn of 1984, Bob Geldof, lead singer with moderately successful rock/ pop band The Boomtown Rats, was watching the BBC’s Nine O’ Clock News in bed with a cold, and witnessed a report that shook him and the entire British nation at large. In it, reporter Buerk not just broke the news that swathes of Ethiopia’s population were suffering from famine owing to record low rainfall, lack of government preparation in the face of this and insurgencies and counter-insurgencies in the north of the country, but he and his team managed to hammer the message home thanks to the shots of the human tragedy they couldn’t fail to capture on film. Geldof was as moved as the rest of the UK at what he’d seen, but unlike the rest of the UK, was also stirred into action.

Back for more: the Band Aid single’s iconic cover art designed by Peter Blake (left); Geldof, Ure, Elton John, the BBC’s Janice Long and others at the June ’85 launch of Live Aid (centre); and the event’s ‘Global Jukebox’ promotional poster

What he did next has become notorious, of course, but needs to be recalled once more, as it was the first act in the Live Aid story. The charity single, the profits from which he planned would help feed the masses of starving Ethiopians, that he organised with Ultravox’s Midge Ure was Do They Know It’s Christmas? and, produced with the efforts – free of charge – from British rock and pop’s top alumni, it became an utter phenomenon. The song was released in late November 1984, outsold every single on the UK chart combined in its first week on release, remained at Number 1 for another four weeks (including taking the coveted Christmas Number 1 slot) and raised millions, as opposed to Geldof’s much more conservative target of a mere £70,000.

Band Aid, as the project was nattily entitled, necessarily created an aid programme, given that Geldof and Ure’s next immediate problem was working out where and how to dish out the dosh. Not only had they set up a charity (The Band Aid Charitable Trust) the day they recorded their song, they were now also running it. However, Geldof wasn’t content with just this. The Ethiopian famine was never going to be eradicated by one charity single – however big that was – and, unsurprisingly, the starving carried on into 1985. More aid was needed. Bob decided he had to push on, go further, do something bigger, really reach for the sky… if he could.

And one morning in June, together with entertainment promoter Harvey Goldsmith, he went live on the the BBC’s Radio 1 station to announce to the world that Live Aid would take place on 13 July, just weeks away. Billed as ‘the global jukebox’, the event would feature two concerts – if not more – that would run more or less simultaneously in the United States and at Wembley Stadium in London. During the same broadcast, Geldof regaled listeners with a long set-list, in alphabetical order, of artists who would definitely be performing on the day. The list was impressive, to the say least, but what punters didn’t know as they scrambled to buy tickets for the show was that a large number of the artists Geldof announced hadn’t agreed to perform – some of them were yet to be even contacted. Moreover, seconds before the broadcast began, he had been told that his team had just got through to representatives of The Who to discuss their involvement, and for Bob that was enough – he finished his set-list announcement by declaring he’d just been informed that The Who were reforming especially for the concert and would performing along with everybody else. On hearing the news both Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend separately called Bob’s people to find out just what the hell was going on.

“It’s twelve noon in London, seven am in Philadelphia, and around the world it’s time for Live Aid!” ~ BBC broadcaster Richard Skinner’s memorable opening

But it was a clever game Geldof was playing. In order to get potential performers’ backsides into gear and make them commit, he knew he’d have to use unorthodox methods. In most cases he played them off against each other – he’d phone ‘artist A’ and tell them they had to be on the bill because ‘artist B’ was, and then phone ‘artist B’ and tell them they had to be on it because ‘artist A’ was. Eventually, with the aid of the behind-the-scenes contacts and fellow scheming of Goldsmith, his bloody-minded bullying paid off and the bill fell into place, but only around a fortnight before the event itself.

The watershed moment came when Dire Straits realised they were down to play Wembley Arena (a venue related to the stadium, but effectively across the road from it), so they told Geldof and co. they would be able to play Live Aid as long as their set allowed them to finish in time to get across to Wembley Arena and do the pre-arranged gig. Being able to allot Dire Straits a time, therefore, Geldof could then go to the others and tell them that not only did he have that highly respected band in the bag, but also the time they’d be on. The other artists now jumped at the chance to be involved and seek the best performance times for their own sets.

One performer proved to be elusive all along, however; the performer who for the Live Aid organisers was ‘the big one’ – the artist whose involvement, they believed, could make or break the event as he would lend the whole shebang genuine legitimacy in the eyes of political movers and shakers. Well, he was rock music royalty, after all, given he was Paul McCartney. When a delegation finally got an appointment set up to meet with him, Macca took them aback a little by saying he had no objection whatsoever about appearing (although he had effectively been on a performing hiatus since John Lennon’s death at the end of 1980). He claimed he had no alternative than to appear because ‘the management’ had ordered him to do so; after some confusion, he explained to Geldof’s representatives that ‘the management’ was his children.

If organising the Wembley side of Live Aid was like a bad dream, then getting the US side going was a proper nightmare. The idea of holding such a huge fund-raising concert in the States – especially it being co-ordinated with another concert in another country and the whole thing being run outside the States – was always an ambitious aim; from the start, Goldsmith felt it might prove to be a pipe-dream, but Geldof (always with the big picture in mind of the money that needed raising) was adamant it had to happen and persevered. The big problem was that nobody in the States really believed that the project could be pulled off – hardly Bob’s ‘just bloody do it’ attitude.

Things came to a head when Geldof and Goldsmith realised that controversial music promoter Bill Graham, Live Aid’s US organiser, was telling performers, whom he was supposed to be securing for the bill, that the whole thing would be a disaster and appearing on it woud damage their careers. Quite clearly his real interest was developing and talking up his own promotional projects, often at Live Aid’s expense. Unsurprisingly, Graham was given the heave-ho and eventually, with just one week to go to the event itself, the US side of things was sorted out and artists secured for its bill. Nevertheless, major names who were included in early Live Aid promotional material for the concert at Philadelphia’s JFK Stadium, but eventually didn’t materialise, included Rod Stewart, Stevie Wonder, Billy Joel, Boy George, Tears For Fears, Kris Kristofferson, Huey Lewis And The News and Paul Simon. The latter two acts have since claimed they pulled out owing to disagreements with Graham.

However, both concerts did end up with strong line-ups to say the least (a full list of both follows at the bottom of this blog), and now – with just days to go – the organisers could turn their attention to the logistical problems of getting the concerts up and running. Problems that needed to be overcome at Wembley included the stadium seeking payment for its use, while everyone else involved was doing it all gratis, given the cause. This stance left Bob fuming and a showdown with Wembley’s chief – that featured an f-word splattered tirade from the former – did little to find a compromise.

Royal salute, chanteur in boots: Geldof and his rock pals with Charles and Di as the day opens (left); later, Bono gets soulful before his infamous – and heroic – foray into the crowd (right)

Finally, one was reached, though, and thoughts quickly shifted to installing the revolving stage at the stadium, which had been boasted about in promotional material as state-of-the-art and, thus, quite the boon. In the event, it looked like it might be more of a boob, for, as it was being put in with a day to go, the thing clearly didn’t want to work properly. Eventually, though, it did work – sort of. Big blokes pulling on ropes to make the cogs go round, and in turn, the stage go round proved the answer. Like much to do with Live Aid, given the sort of event it was, arrangements for the stage were made on the fly – it was, in fact, a controversial stage design that dated back three years and on the one previous occasion it had been tried out for a concert in Sweden, it hadn’t work then either.

Aside from obvious logistics, the actual broadcasting – and the co-ordination necessary therein – of the day itself were enormous. A staggering total of 16 satellites were necessary to bounce images to TVs around the globe – easily ensuring Live Aid was, at the time, the world’s most ambitious satellite television broadcast (things had come a long way since The Beatles sang All You Need Is Love to world in 1967). The BBC were only too happy to take on television and radio duties in the UK, while the ABC network chiefly took on television duties in the States (albeit with commercial breaks and replaying major moments from both concerts in US prime-time whatever was happening live). In addition, the relatively new US phenomenon that was MTV broadcast the event on its cable-only channel. To its credit, unlike ABC, the Beeb tried to broadcast the best of both concerts live – per Geldof’s initial notion behind the ‘global’ event, so that viewers would see whatever was going on live wherever it was going on in the world. However, this sometimes proved impossible even for them, as, for instance, they had to miss Crosby, Stills & Nash’s reunion at JFK Stadium owing to covering what was going on at Wembley at that point. In spite of all that, the Beeb did supply a ‘clean feed’ to TV networks acoss Europe.

One idea that was dropped simply because it was too difficult to pull off was the novelty of Mick Jagger and David Bowie dueting on a song in the two different stadia; Jagger at JFK Stadium, Bowie at Wembley. Sadly, among several other mooted difficulties, the final nail in the coffin was the reality that the satellite feed to either stadium would lag a few seconds behind what happened in real-time, thus, no transatlantic co-performance would be possible unless one of the artists mimed, something neither of them were up for. Still this wasn’t actually the most outlandish idea proposed for the Jagger/ Bowie duet – some bright spark suggested they might be put in a rocket, blasted out into space and do it from there. Admittedly, the notion didn’t get beyond the brainstorming stage; although it didn’t stop Goldsmith vainly phoning NASA to check out its viability.

Other side of the pond: guitar gods Wood, Dylan and Richards rock out (left); Black Sabbath’s Ozzy Osbourne cools off (centre); and a fully-clothed Madonna gets into the groove (right)

In the end, unbeknown to Geldof (he was rather happy when he found out about it), Jagger and Bowie made up for the ruled-out on-the-day duet by recording a duet cover of Martha And The Vandellas’ Dancing In The Street, the proceeds from which would go to Live Aid. When released shortly after the event, it reached Number 1 in the UK charts (staying there for four weeks) and Number 7 in the US. Jagger and Bowie did perform at Live Aid, though, but separately; the former with others in Philadelphia, the latter in London.

Mind you, another outlandish and terribly gimmicky plan for the day did come off – and very well. Following completion of his set at Wembley (shared with Sting), Phil Collins was helicoptered by Noel Edmonds – yes, you read that right, Noel Edmonds – to Heathrow Airport, and flown on Concorde to Philadelphia where he performed another set at the JFK Stadium, all of nine hours after his UK one had finished. Not just that – like he did on the Band Aid single – he also played drums for others, namely for Eric Clapton and the Led Zeppelin reunion in Philadelphia. All didn’t quite go swimmingly, however. When interviewed on Concorde by the Beeb’s presenter at Wembley, the feedback was so awful Collins’ responses could barely be heard, while the baldy baladeer also scuffed an opening piano note of Against All Odds (Take A Look At Me Now) in his first set. Not that he was the only one, though. Later on, Simon Le Bon delivered an utterly unintended falsetto note at the JFK Stadium, while his band Duran Duran performed the very recently released hit A View To A Kill, the theme song from the Bond film of the same name. Media outlets were to enjoy themselves later by rather cruely referring to Le Bon’s slip as ‘the bum note heard around the world’.

In fact, cock-ups, perhaps unsurprisingly, ended up being the order of the day. While thankfully there weren’t any major problems with Wembley’s revolving stage, a fan at the front of the crowd was almost crushed to death during U2’s set. Critics for years lambasted frontman Bono’s seemingly self-indulgent behaviour when he went on a ‘walkabout’, not realising until recently the reason why he jumped down from the stage and pulled the girl out of the throng wasn’t actually because he wanted to be seen dancing with her. He had gestured to ushers to help her, but they hadn’t understood what he was meaning. And, yes, this all took place while he was crooning – just goes to show then, Bono really does want to save the world; he’ll even try and do it one person at a time. While he’s singing.

Also, during The Who’s performance of Won’t Get Fooled Again, with quite brilliant timing, the Beeb’s TV feed momentarily went down immediately following the word ‘fade’ as Roger Daltrey sang the line ‘Why don’t you all fade… away’. Less amusingly, though, as the Wembley leg approached its climax, Paul McCartney’s much anticipated set was jeopardised by yet more technical gremlins as the first two minutes of his performance of Let It Be ended up wordless because his mircophone wasn’t on. He later joked he’d contemplated changing lyrics in the song to ‘There will be some feedback, let it be’.

However, for the most part, of course, both concerts confounded the critics, as they proved to be huge successes. Far from looking upon their participation as possibly ruining their careers, as Bill Graham had ‘warned’ some it might, most of the artists saw the concerts as as a great opportunity to boost their careers, realising the potential global audience that would be watching on TVs all over the planet. And thus, they all went for it with gusto. Rather bizarrely, even back then, the Wembley gig was opened by ageing rockers Staus Quo. Yet, their opening song choice proved to be genius – Rocking All Over The World went down a storm with the crowd, who on a hot day were all cooped up in the stadium and excited beyond belief for what might come. More contemporary acts such as The Style Council, Dire Straits, Bryan Adams, Power Station, Run-DMC and Duran Duran (as mentioned) were no mugs either, using the event to showcase recent and/ or new tunes; while, in no need of any publicity herself, Madonna, one of the biggest draws of the JFK Stadium event, referred directly to her own publicity when, insinuating her recent disrobing for both Playboy and Penthouse magazines and making a nod to the day’s stifling heat, she memorably exclaimed: “I’m not taking s*** off today!”.

And, although Bono’s off-stage antics ensured they had to strike third song Pride (In The Name Of Love) from their set, U2 nonetheless lodged themselves firmly in music fans’ minds thanks to their Live Aid performance – one that was full of their frontman’s customary charisma. So much so, their apearance really helped push them down the road to rock superstardom, which, naturally, would be theirs come the end of the decade. Plus, in spite of the technical hitches, the ‘reunion’ sets of The Who, Led Zep and Crosby, Stills & Nash (and Young) proved quality highlights, while the two performances of Phil Collins, as well as those of the ever popular Elton John, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan (with Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood) and – albeit separate – Bowie and Jagger were durable and dependable performances. Even Band Aid co-organiser Midge Ure got in on the act with Ultavox and Geldof himself with The Boomtown Rats (as if anyone was actually going to stop him, mind). In fact, another the of day’s most memorable moments came when, towards the end of the song I Don’t Like Mondays, Bob stopped dead after the line ‘And the lesson today is how to die’. The double meaning he intended this line to take on by pausing in this way, given the day’s cause, wasn’t lost on the Wembley crowd as they applauded the thought – and probably Geldof’s organisation of the whole thing – before singing out the rest of the song themselves.

“F*** the address, let’s get the numbers!” ~ how an angry Bob Geldof really used the f-bomb (instead of the misquoted ‘Give us your f***ing money!’) live on British teatime TV, when his interviewer suggested repeating the address money could be sent to, instead of repeating the phone numbers that could more immediately and reliably bring in donations

In spite of all this, though, such huge musical events as these always seem to boast star turns (take Hendrix at Woodstock), and Live Aid in ’85 was no exception. There was a band that wasn’t for a second overawed by the magnitude of the day and, thus, did more than turn out a professional, entertaining performance; quite simply, they took the thing by the scruff of the neck and rocked Wembley’s socks off. And, at the time at least, it was somewhat surprising that that band was Queen. It seems rather bizarre now, but Queen’s popularity had waned a little by the mid-’80s; not only had their following in the States subsided from its ’70s high, but they were also reeling from the controversy their performing in the apartheid-locked South Africa the previous year had created. Yet, you can’t keep a good band down – not least the most grandiose and theatrical of the greats – and Queen grabbed Live Aid by the jugular. It was an event made for them, and they were made for it.

Right from the off, as they were introduced in a wonderfully random manner by comedians Smith and Jones dressed up as policemen ‘complaining’ about the noise, they were greeted by a roar. Lead singer Freddie Mercury led his band bounding on to the stage and, sitting at the piano, quickly launched into the all-time classic Bohemian Rhapsody. This was followed up by the ebullient Radio Ga Ga, and it was during this tune that it happened – Mercury the frontman with the charisma of a thousand Robert Plants captured the stadium’s capacity crowd of 72,000 people, every last one of them, and didn’t let go. The moment you realise – and he realises – he’s got them in the palm of his hand is when every single person appears too be hand-clapping in unison during the first chorus; just watch this blog’s second youtube clip – I defy the hairs on the back of your neck not to stand on end. It’s electric stuff, truly. After all, the majority of the crowd weren’t necessarily Queen fans; they were there for the event itself and all the acts combined.

Following Radio Ga Ga, Mercury indulged himself by getting the crowd to repeat his vocal training pastiche – something he would always do at Queen concerts – but they were with him all the way. As they were through the rest of the set: Hammer To Fall, Crazy Little Thing Called Love, We Will Rock You and We Are The Champions – the lines of the last two, the crowd seemed to sing word for word. To say this set was a bravura perormance doesn’t do it justice. In a 2005 poll conducted by British television’s Channel 4, Queen’s Live Aid appearance was voted the greatest ever live gig – and surely rightfully so.

However, Live Aid really really did turn out to be such an extraordinary event that, one could argue, these few minutes of magic were topped by something even more powerful and moving. It came immediately after David Bowie’s set (which followed Queen’s); in fact, he introduced it – and one might say it’s to blame for all the oh-so obvious guilt-inducing musical montages that every telly charity-a-thon worth its salt is chockful of nowadays. Edited together by Canadian Broadcasting Corporation engineer Colin Dean, it was a video film that showed images of starving, diseased and – perhaps even – dying people as a result of the Ethiopean famine, the vast majority of them children. And over the top of it was played The Cars’ hit song Drive.

It’s only rock ‘n’ roll, but they like it: (from left) George Michael, Harvey Goldsmith, Bono, Paul McCartney and Freddie Mercury enjoy themselves during the Wembley gig’s big finish

Dean has since explained that he had been listening to the song and, only semi-seriously, wondered whether it may fit the video he had to cut together, yet soon he found himself mirroring images to lines in the song. The way the video was constructed then, and thus the way it sought to manipulate the emotions was about as subtle as Spielberg had done in making E.T., but the effect was devastating. As it was broadcast – and simultaneously played on the stadium’s big screens – the bouyant, bouncing festival atmosphere in Wembley was cut to pieces; it was a sudden, unequivocal reminder to the revellers what the day was really all about, just as it proved to be for all those watching at home . Apparently, the rate at which punters phoned in to give money increased dramatically in the minutes afterwards. So, this video (which actually owed its place in the bill to Bowie suggesting he cut a song from his set so it could fit in the schedule) had played its part perfectly and all these years on it’s still so memorable. Honestly, I can’t think of, or hear, the wonderful Drive by The Cars without my mind immediately flooding back to those images, and I very much doubt I’m alone in that either.

In the event, it was all worth it – the video and all the acts at the Wembley and JFK Stadiums, and all the frenzied flapping that had gone on before to pull it off. Live Aid was watched, live, in 60 countries by an estimated 2 billion people. And thanks to their combined dipping into the kitty, a final figure of £150 million was raised – and, let’s not forget, that’s £150 million in 1985 money. One has to wonder how Bill Graham and the naysayers felt after that. Deservedly so, Geldof was given a honoury knighthood and – before that – was hoistered on the shoulders of Pete Townshend and Macca at the end of an inevitable rendition of Do They Know It’s Christmas? at the close of the Wembley concert.

Twenty years later in 2005, Bob and co. felt it worth another go and put on Live 8, which if anything was even bigger – unlike in ’85, there were eight concerts all over the world, in addition to the two mega-gigs in the UK and the US (although, admittedly, back in ’85 there were also token efforts held in Australia, Germany, Holland, Yugoslavia and Russia). But, given Live 8’s purpose was to raise awareness – not dosh – about general poverty in order to put pressure on politicians to eradicate African and Third World debt, the aim seemed less pointed and immediate than its predecessor. Cynicism abounded about whether it could make a difference – and, sadly, five years on, the global recession looks to have put paid to much of the work it did in forcing the West’s hand to help out Africa’s finances.

The truth, then, is that Live Aid was a real one-off. A wonderful and, for the most part, selfless event that came slap-bang halfway through one of the greediest and selfish decades the world has ever known. Looking back, there’s something terrifically ironic and pleasing about a bunch of New Romantics with all their mullets, hair lacquer and crazy long jackets coming together with their synthesizers, guitars and drum-machines and asking the world to help out a country’s population that was staring into the abyss. And it worked; for one day, the world really was united and did exactly what it should do. Queen and co. promised ‘we will rock you’ and the world responded. Sometimes when the will is there, it can be – and is – that gloriously simple…

Live Aid set-lists (artist start-times – in BST – in brackets):

Wembley Stadium

- Coldstream Guards – Royal Salute/ God Save the Queen (12:00);

- Status Quo – Rockin’ All Over the World/ Caroline/ Don’t Waste My Time (12:02);

- The Style Council – You’re The Best Thing/Big Boss Groove/ Internationalists/ Walls Come Tumbling Down (12:19);

- The Boomtown Rats – I Don’t Like Mondays/ Drag Me Down/ Rat Trap/ For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow (sung by the audience) (12:44);

- Adam Ant – Vive Le Rock (13:00);

- Ultravox – Reap the Wild Wind/ Dancing with Tears in My Eyes/ One Small Day/ Vienna (13:16);

- Spandau Ballet – Only When You Leave/ Virgin/ True (13:47);

- Elvis Costello – All You Need Is Love (14:07);

- Nik Kershaw – Wide Boy/ Don Quixote/ The Riddle/ Wouldn’t It Be Good (14:22);

- Sade – Why Can’t We Live Together/ Your Love Is King/ Is It A Crime (14:55);

- Sting and Phil Collins (with Branford Marsalis) – Roxanne/ Driven To Tears/ Against All Odds (Take a Look at Me Now)/ Message in a Bottle/ In the Air Tonight/ Long Long Way To Go/ Every Breath You Take” (15:18);

- Howard Jones – Hide and Seek (15:50)

- Bryan Ferry (with David Gilmour on guitar) – Sensation/ Boys And Girls/ Slave To Love/ Jealous Guy (16:07);

- Paul Young – Do They Know It’s Christmas? (intro)/ Come Back And Stay/ That’s the Way Love Is (with Alison Moyet)/ Every Time You Go Away (16:38);

- U2 – Sunday Bloody Sunday/ Bad (with bits of Satellite Of Love, Ruby Tuesday, Sympathy for the Devil and Walk On The Wild Side) (17:20);

- Dire Straits – Money for Nothing (with Sting), Sultans of Swing (18:00);

- Queen (introduced by Mel Smith and Griff Rhys Jones) – Bohemian Rhapsody/Radio Ga Ga/ Hammer to Fall/ Crazy Little Thing Called Love/ We Will Rock You/ We Are the Champions (18:44);

- David Bowie – TVC 15/ Rebel Rebel/ Modern Love/ Heroes (19:22);

- The Who – My Generation/ Pinball Wizard/ Love Reign O’er Me/ Won’t Get Fooled Again (20:00);

- Elton John (introduced by Billy Connolly) – I’m Still Standing/ Bennie and the Jets/ Rocket Man/ Don’t Go Breaking My Heart (with Kiki Dee)/ Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me (with George Michael and backing vocals by Andrew Ridgeley)/ Can I Get a Witness (20:50);

- Finale:

~ Freddie Mercury and Brian May – Is This The World We Created? (21:48),

~ Paul McCartney – Let It Be (21:51),

~ Band Aid (led by Bob Geldof) – Do They Know It’s Christmas? (21:54)

JFK Stadium

- Bernard Watson – All I Really Want to Do/ Interview (13:51);

- Joan Baez (introduced by Jack Nicholson) – Amazing Grace/ We Are the World (14:02);

- The Hooters – And We Danced/ All You Zombies (14:12);

- The Four Tops – Shake Me, Wake Me (When It’s Over)/ Bernadette/ It’s The Same Old Song/ Reach Out I’ll Be There/ I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) (14:33);

- Billy Ocean – Caribbean Queen/ Loverboy (14:45);

- Black Sabbath (introduced by Chevy Chase) – Children of the Grave/ Iron Man/ Paranoid (14:52);

- Run-DMC – Jam Master Jay/ King Of Rock (15:12);

- Rick Springfield – Love Somebody/ State Of The Heart/ Human Touch (15:30);

- REO Speedwagon – Can’t Fight This Feeling/ Roll With The Changes (15:47);

- Crosby, Stills and Nash – Southern Cross/ Teach Your Children/ Suite: Judy Blue Eyes (16:15);

- Judas Priest – Living After Midnight/ The Green Manalishi (With The Two-Pronged Crown)/ You’ve Got Another Thing Comin’ (16:26);

- Bryan Adams (introduced by Jack Nicholson) – Kids Wanna Rock/ Summer of ’69/ Tears Are Not Enough/ Cuts Like a Knife (17:02);

- The Beach Boys (introduced by Marilyn McCoo from The 5th Dimension) – California Girls/ Help Me, Rhonda/ Wouldn’t It Be Nice/ Good Vibrations/ Surfin’ USA (17:40);

- George Thorogood and the Destroyers – Who Do You Love (with Bo Diddley)/ The Sky Is Crying/ Madison Blues (with Albert Collins) (18:26);

- Simple Minds – Ghost Dancing/ Don’t You (Forget About Me)/ Promised You a Miracle (19:07);

- The Pretenders – Time The Avenger/ Message of Love/ Stop Your Sobbing/ Back On The Chain Gang/ Middle of the Road (19:41);

- Santana and Pat Metheny – Brotherhood/ Primera Invasion/ Open Invitation/ By The Pool/ Right Now (20:21);

- Ashford & Simpson – Solid/ Reach Out and Touch (Somebody’s Hand) (with Teddy Pendergrass) (20:57);

- Madonna (introduced by Bette Midler) – Holiday/ Into the Groove/ Love Makes The World Go Round (21:27);

- Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers (introduced by Don Johnson) – American Girl/ The Waiting/ Rebels/ Refugee (22:14);

- Kenny Loggins – Footloose (22:30);

- The Cars – You Might Think/ Drive/ Just What I Needed/ Heartbeat City (22:49);

- Neil Young – Sugar Mountain/ The Needle And The Damage Done/ Helpless/ Nothing Is Perfect/ Powderfinger (23:07);

- Power Station – Murderess/ Get It On (23:43);

- Thompson Twins – Hold Me Now/ Revolution (with Madonna, Steve Stevens and Nile Rodgers) (00:21);

- Eric Clapton (with Phil Collins) – White Room/ She’s Waiting/ Layla (00:39);

- Phil Collins – Against All Odds (Take a Look at Me Now)/ In the Air Tonight (01:04);

- Led Zeppelin Reunion – (with Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones, Tony Thompson, Paul Martinez and Phil Collins) – Rock and Roll/ Whole Lotta Love/ Stairway to Heaven (01:10);

- Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young – Only Love Can Break Your Heart/ Daylight Again/ Find the Cost of Freedom (01:40);

- Duran Duran – A View to a Kill/ Union Of The Snake/ Save a Prayer/ The Reflex (01:45);

- Patti LaBelle – New Attitude/ Imagine/ Forever Young/ Stir It Up/ Over The Rainbow/ Why Can’t I Get It Over (02:20);

- Hall & Oates – Out of Touch/ Maneater/ Get Ready (with Eddie Kendricks of The Four Tops)/ Ain’t Too Proud to Beg (with David Ruffin of The Four Tops)/ The Way You Do the Things You Do/ My Girl (with Eddie Kendricks and David Ruffin) (02:50);

- Mick Jagger (with Hall & Oates, Eddie Kendricks and David Ruffin) – Lonely At The Top/ Just Another Night/ Miss You/ State of Shock/ It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll (But I Like It) (with Tina Turner) (03:15);

- Finale:

~ Bob Dylan, Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood – Ballad of Hollis Brown/ When the Ship Comes In/ Blowin’ in the Wind (03:39),

~ USA for Africa (led by Lionel Richie) – We Are the World (3:55)

~~~

Further reading:

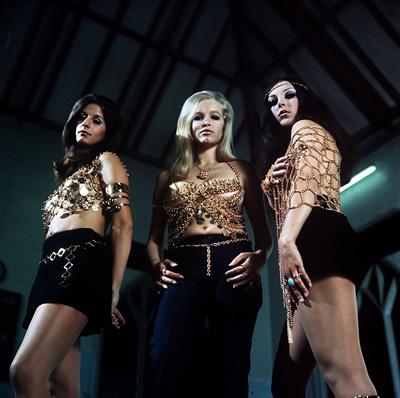

Pan’s People: Dancing Queens

.

Talent…

.

… These are the lovely ladies and gorgeous girls of eras gone by whose beauty, ability, electricity and all-round x-appeal deserve celebration and – ahem – salivation here at George’s Journal…

.

Always Dad’s favourite and often the highlight of Top Of The Pops, they were the madams with the moves, the coquettes in the costumes and the bods for the mod times – they were fun, frolicsome, a bit fancy, but always family-friendly; they were Pan’s People and they were most definitely Talent, five or six doses of it all in one go…

.

Profile

Name: Pan’s People

Members: Louise Clarke (1968-74), Felicity ‘Flick’ Colby (1968-71 dancer/ 1971-76* choreographer); Barbara ‘Babs’ Lord (1968-75); Ruth Pearson (1968-76); Andrea ‘Andi’ Rutherford (1968-72); Patricia ‘Dee Dee’ Wilde (1968-75); Mary Corpe (1975-76*); Cherry Gillespie (1972-76*); Susan ‘Sue’ Menhenick (1974-76*); Lee Ward (1975-76*)

Nationality: British

Profession: Dance troupe

Known for: Performing light-hearted and cheeky dance routines on the BBC’s weekly chart music show Top Of The Pops during the early- to mid-1970s, when live performances of particular songs or video films for them weren’t available; as well as public appearances throughout the decade and performances on the BBC’s 1974 In Concert TV series and, occasionally, The Two Ronnies sketch show.

Strange but true: Pan’s Person Babs Lord went on to marry actor Robert Powell and became an amateur yachtswoman and explorer – travelling to the Himalayas, the Sahara and the Guyanan jungle, and is the oldest housewife to have visited both the North and South Poles. Also, Cherry Gillespie went into acting and appeared in the James Bond film Octopussy and episodes of Bergerac and Minder.

Peak of fitness: Dancing along to Van McCoy And The Soul City Symphony’s The Hustle on Top Of The Pops, while all wearing terribly short white, frilly, feathery dresses

* Pan’s People continued as a group of dancers beyond 1976, but their final Top Of The Pops performance was broadcast in April 1976

.

CLICK on images for full-size

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.