Legends: Terry Wogan ~ the blarney marvel

Pudsey’s pal: the bear may have a bandaged eye, but there’s been a twinkle in Terry Wogan’s for more than 40 years – during which he’s become a charity ringmaster and national treasure

Let’s face it, Children In Need is unimaginable without him, he was the voice of Eurovision for an entire generation, he ruled the breakfast airwaves like nobody before or since and he may just have been around for as long as Brucie. He’s Terry Wogan; the Irish broadcaster blessed with über-blarney who seems to have helped make Britain what it is today. And he is, unquestionably, the latest deserved inductee into the Legends corner here at George’s Journal.

Yes, for decades the screens in the corners of the country’s living rooms and the radios on the shelves of its kitchens have been the home of Wogan. Neither audiovisual appliance – indeed, maybe none of them in any British home – has ever been free of the man’s sardonic yet cheery expression and the lilting tones of his soft brogue. There have been many imports from the Emerald Isle that, over the years, have enriched these fair islands – Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Swift, even Dave Allen – but none have fitted quite so seamlessly, so cosily and seemingly so effortlessly into the UK consciousness as the Togmeister himself, Terry Wogan.

He was born Michael Terence Wogan on August 3 1938 in Limerick, the largest city in the Irish county of the same name. His father was a grocery store manager and saw to it that the young Terry had a strong religious upbringing, the latter attending the fee-paying Jesuit secondary school Crescent College from the age of eight. When Wogan senior was made a general manager, he moved his family to the Irish capital Dublin and Terry, now 15, joined Crescent College’s sister school in the city, Belvedere College.

All the Catholic doctrine and culture absorbed by the child and adolescent Wogan was to have a profound effect on him – but surely not the one his father had envisaged: the former turned away from the church. Indeed, in later years (2004 to be exact), he remarked on his upbringing: “There were hundreds of churches, all these missions breathing fire and brimstone, telling you how easy it was to sin, how you’d be in hell. We were brainwashed into believing”.

At Belvedere he developed an artistic bent, participating in school plays, and became interested in early rock ‘n’ roll. Yet, his career that would become synonymous with pop music was not to start until later. For, on leaving school around the age of 18, he was employed at a branch of the Royal Bank of Ireland in Dublin. Fairly soon, however, he realised banking wasn’t for him and applied for a position he saw advertised in a local paper for an announcer with the Irish national broadcaster Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ). Securing the post, Wogan had now entered the heady world of broadcasting – and wouldn’t look back.

Man and wife and hitting the heights: Terry and wife Helen in 1970 (l), getting chummy with Bond star Roger Moore (m) and flying on a wire during a Christmas edition of Blankety Blank (r)

Unlike, say, Chris Evans, though, he wasn’t exactly an overnight success. It wouldn’t be for the best part of 10 years yet that Terry would make his name and eventually cross the Irish Sea. Over the next decade then, he learnt this trade. In his first couple of years with RTÉ, he found a niche for himself as an interviewer and presenter of documentary features. He then moved on to the entertainment department and – for the first time – worked as a disc jockey, as well as a TV variety show host. One such programme he fronted was a favourite with the viewers, the quiz show Jackpot, which established Terry as an Irish media celebrity. In short, he’d made it.

In reality, his father had always wanted him to be a doctor, but Terry knew he had found his calling – plus, in school at least, he’d never really worked hard enough to stand a chance in the medical profession. “I only ever did enough to pass exams,” he confessed later. “I never had any capacity for preparing for anything. That’s why I’m so lucky to be in a job where I make it up as I go along.”

Indeed, as if making it up as he went along, when RTÉ dropped Jackpot Terry took an unusual step for an Irish broadcaster – he approached the BBC for work. Perhaps to his surprise, perhaps not, the Beeb, recognising his talent, acquiesced and on September 27 1966, he appeared on the British airwaves for the very first time as he presented on The Light Programme (the forerunner to Radio 2) ‘down the line’ from Dublin.

The big change for Wogan and family (by now he was married – he’d tied the knot with Helen Joyce in April ’65 and together they’d have three children across the late ’60s and early ’70s) came with the establishment of Radio 1 at the end of September 1967. Conceived as the Beeb’s alternative to the now illegal offshore ‘pirate’ stations, such as Radio Caroline, that had built a dedicated audience among the turned-on, tuned-in ’60s youth, it quickly proved hugely popular with this demographic – a position it’s cannily never relinquished – maybe thanks to poaching many of the pirate stations’ best loved DJs.

.

Wogan, obviously, wasn’t one of them, but that didn’t stop him from fronting the Tuesday edition of Late Night Extra for two years. And this led to him covering colleague Jimmy Young’s mid-morning show throughout July ’69, which in turn led him to being offered the 3-5pm afternoon slot permanently. He readily accepted it and enjoyed being broadcast simultaneously on Radio 2 as well as Radio 1 owing to budget shortages. During this time he also undertook a regular and unenviable commute from his family in Dublin to his studio in London.

The move to Radio 2 alone came in April 1972 when he took on the mantle of the station’s breakfast show – the broadcast with which he’d become most associated for the rest of his career. With his family now ensconced in Blighty and he himself having found his natural home at the nation’s most cosy-cum-populist media outlet, Wogan became the huge star the twinkle in his eye must have always threatened he’d become.

In the ’70s (as well as, admittedly, every subsequent decade) there was simply no avoiding him. If he wasn’t waxing lyrical on the wireless to Britain’s waking masses, he was on the box presenting the Blackpool-based ballroom-dance-focused show Come Dancing (1949-98) or, yes, commentating on The Eurovision Song Contest for the BBC (he did so first on the radio in ’71, from ’74 to ’77 and again in ’79; he did so on TV in ’73, again in ’78 and forever after from 1980 – see middle video clip).

His first filling of the Radio 2 breakfast show’s chair would last for more then 10 years, during which time he built up a daily audience of nearly eight million listeners. His brand of easy-going, mellow Irish tones blended with knowing, near over-verbose wit proved a fine fit with large numbers of the nation over 25 who preferred not to wake to the likes of Tony Blackburn, Noel Edmonds or Dave Lee ‘The Hairy Cornflake’ Travis and their start-the-day diet of ’70s pop and rock on Radio 1.

Inevitably, Wogan’s ubiquity drew mockery from some quarters, but all of it good-natured. For example, both the comedy trio The Goodies on their madcap BBC2 show (1970-80) and the popular humour-based folk pop group The Barron Knights made him the butt of many jokes. And, being a master of self-deprecation (which has always been among the biggest aspects of his appeal), Terry himself was adept at taking the mickey out of himself. In fact, then – as now – he revelled in it.

Cartoon characters: with a thrice-weekly chat show, Wogan suffered from overexposure in the ’80s (l), but his 1991 encounter with fantasist David Icke was cracking car-crash television (r)

A case in point was his release in 1978 of The Floral Dance, whose instrumental version by The Brighouse and Rastrick Brass Band had hit #2 in the UK charts at Christmas the year before; Wogan’s take on it reached #21. Surely only hard-hearted souls begrudged Terry this indulgence, though, as he’d played a descisive role in the tune’s first chart success – it had been him who’d brought it to peeps’ attention in the first place by playing it on his show as he, er, sung the lyrics over the top of it. Buoyed by this admittedly dubious musical success, he released both a follow-up single Me And The Elephant and a self-titled album, neither of which (probably rightly rather than wrongly) made it into the charts.

In 1984 Wogan made the decision to focus on his TV career full-time, handing over the reins of the breakfast show to Ken Bruce. Aside from his frequent work on Come Dancing and for Eurovision, he’d already scored a big hit on the box with the so-bad-it-was-brilliant celebrity panel- and double entendre-driven gameshow Blankety Blank (1979-90); the premise of which seemed to be for its hosts and guests to wallow in its cheap and tacky production values as much as possible.

The public loved it, especially on one occasion when Radio 1 DJ guest Kenny Everett grabbed the end of ‘Wogan’s Wand’, his trademark car aerial-style microphone (which, true to the show’s cheapness, actually was an adjusted car aerial), and bent the thing to a ridiculous angle, forcing the former to carry on with the intrument in that condition for the rest of the recording. Whenever Everett guested on the show thereafter, he’d scupper the microphone each time – once doing so by attempting to cut it in two with a giant pair of scissors. Over 20 years later, Wogan himself would destroy his wand – as it were – for comic effect in a one-off Blankety Blank special broadcast as part of a Children In Need night.

Terry quit Blankety Blank the year before he finished on Radio 2, to be replaced as host by comedian Les Dawson. As it was now the ’80s, perhaps inevitably he moved on to the abundant TV variety show of the age: the chatshow. The first he fronted was BBC1’s Saturday evening effort What’s On Wogan? (1980), which although only boasting a single series gave him an important grounding in the format and led to 1981’s one-off Saturday Live, on which he interviewed Larry Hagman aka JR Ewing in Dallas (1979-91).

.

In 1982, BBC1 gave him another crack at a series with the simple-as-pie titled Wogan (1981-92). Unlike his previous chatshow, this one quickly gained traction with viewers. In its first season it was brodcast on Tuesday nights, only to be shunted into the late-night Saturday slot vacated by the legendary Parkinson show (1971-82). Here it remained for its next two series until 1985, when it moved back to weekday evenings – broadcast thrice weekly (Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays) – for the rest of its run.

Given the show’s profusion, it became something of a cultural firmament of the decade, featuring many a memorable moment. From Chevy Chase remaining silent throughout an interview to Anne Bancroft appearing to be a nervous wreck during hers and Ronnie Barker announcing his retirement in 1988 to George Best’s unfortunate drunken appearance in 1990 when he told Terry what he enjoyed in life was ‘screwing’, Wogan notched up several impromtu gems.

One such unmissable episode was the host’s encounter in April 1991 with former TV sport presenter David Icke, who claimed that he was the son of ‘a godhead’ and that the Earth would imminently be devastated by tidal waves and earthquakes. Wogan and his audience found Icke’s proclamations both absurd and amusing and, predicatably, it was to become Terry’s most recalled interview – for right or wrong. A few weeks later, Des Christy in The Guardian suggested the show had been a ‘media crucifixion’; indeed, it led to Icke retreating from public life as he became a figure of ridicule. When Wogan interviewed him again in 2006, the former admitted that his comments the first time around may have been ‘a bit sharp’.

The Beeb eventually gave Wogan its marching orders in the early ’90s in order to launch Brit-expats-in-Spain soap opera Eldorado; the latter was an unmitigated flop, but in all fairness the former had really had its day too. It almost felt like Terry had reached the stage where the public had had enough of his mug on the telly (one 1992 poll suggested he was somehow both the most and least popular person in Britain) and, perhaps sensing that, in 1993 he took over the reins of the Radio 2 breakfast show once more. It was a canny move, for after all his TV chatshow years, it was his second stint helping get Middle England out of bed in the mornings that seemed to turn him into a genuine national institution.

Having his cake and eating it?: Terry hosting Eurovision in the UK in 1998 with Ulrika Jonsson (l) and posing with Pudsey and a life-sized ‘Terry cake’ created for Children In Need in 2009 (r)

Officially named Wake Up To Wogan, the broadcast became less a radio show, more a daily check-in with an avuncular commentator on the country at large, as Terry laced observations on a supposedly increasingly ‘PC gone mad’ Britain with absurdist, nay, childish humour thanks, in no small part, to the innuendo-laden stories listeners would send in ostensibly about Radio 2 newsreader John Marsh that spoofed the Janet and John series of childrens’ reading books from the 1950s and ’60s (see bottom video clip).

Wake Up To Wogan‘s popularity saw it regularly attain around eight million listeners – as well as afford its star an army of fans/ followers who nicknamed themselves TOGs (Terry’s Old Geezers and/ or Gals). Just like their hero, TOGs would – and still do – happily embroil themselves in fundraising efforts every year for the one-Friday-night-in-November charity-a-fon that is Children In Need (1979-present), which was first fronted by Wogan in 1980 and every year thereafter. They also, like millions of others, gobbled up albums by both folk pop artists Katie Melua and Eva Cassidy, whose careers were partly kick-started by Wogan championing them on his show (the latter posthumously, of course).

Throughout both the ’90s and ’00s then, thanks to his cosy but wry emplacement on radio, annual hosting of Children In Need (which seems to raise more and more each year; over £30 million last time out) and, of course, his delightfully unrestrained, acerbic commentary to the Beeb’s broadcasts of Eurovision, Terry not only re-established his popularity, but also pulled off the trick of reaching different demographics at the same time – his appeal was equally embraced by the supposedly PC-hating swathes of middle-aged Middle England as well as the kitsch-loving youth who stage camp Eurovision parties every May.

Fittingly, he was given an OBE in 1997, followed up by a knighthood in 2005 (he’s allowed to call himself ‘Sir’ as he nowadays holds British, as well as Irish, citizenship), was announced Radio 2’s ‘ultimate icon’ in 2007 in honour of its 4oth anniversary and, most important of all, was awarded a Gold Blue Peter badge in 2004. Indeed, he may have commentated on his last Eurovision in 2008 and broadcast his last breakfast show in 2009, but is now arguably more popular than ever. No question then, when this year’s Children In Need kicks-off this Friday, I’ll be tuning in, yes, not just because it’s a fantastic charity event but also, well, because it’ll be fronted as always by lovevable old Terry. And I won’t be the only one; TOGs, Eurovision addicts and general TV viewers in their millions will be doing exactly the same – whether they’ll admit it or not. Because it may never have been cool or fashionable to like or even love Wogan, but so many of us do – and, frankly, why the blarney wouldn’t we?

~~~

Those wonderful Woganisms

Ten of the best from our Tel…

“Who knows what hellish future lies ahead? Actually, I do – I’ve seen the rehearsals” ~ at the beginning of the 2007 Eurovision Song Contest

“That’s the same song the French have been singing since they hung the washing up on the Maginot Line” ~ during the 2006 Eurovision effort

“Thank God we’ve all had a few drinks – if anyone can kill a crowd these two can” ~ during another Eurovision, specifically about the presenters

“She and I have taken up the diet of Monsieur Montignac which revolves around goose fat, red wine, cheese and chocolate – so long as you don’t combine it with bread and potatoes” ~ on going on a diet with his wife

“They’re not laughing with you, they’re laughing at you” ~ during his notorious interview with David Icke

“There can be few things more irritating than returning home, braced and fresh-faced from holiday, to find that everyone who stayed at home has got a better tan than you” ~ waxing lyrical about holidays

“They came out in rehearsals looking like the World of Leather – you could have made a couple of settees out of them” ~ another Eurovision quip about the Dutch entry in 1997

“I speak well of the Cypriot entry as I sit next to the Cypriot commentator – and she’s a fine big woman!” ~ and another from the year 2000

“And to sing for Cyprus, and wearing his mother’s curtains – Konstaninos!” ~ on the 1996 Cypriot Eurovision entry

“Be of good cheer, we’re nearly half way through – it’s about this time I reach for the bottle” ~ during the 2001 Eurovision contest

~~~

Further reading:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/pudsey/grants

To donate to Children In Need:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/pudsey/donate

~~~

Children In Need 2011 begins at 7.30pm on Friday November 18 on BBC1

Yuppies, sequels, geeks and gekkos: the 10 ultimate ’80s movies

Greed is good?: Michael Douglas created an icon, Charlie Sheen was full of promise and Daryl Hannah looked pretty in Wall Street, a critique of the yuppie that was received as anything but

Ah, the ’80s… we all remember them, don’t we? On the one hand, consumerism hit top gear, the majority on both sides of the Atlantic got wealthier and ‘pooters started to take over the world; on the other hand, society became strongly politically divided, cynical pop elbowed out quality rock and people decided to dress in fashions even sillier than those of the ’60s and ’70s. But is that the whole story? Well, no. The reality was somewhat more complicated. And, despite the rose-tinted view many hold when recalling movies from that decade as easy-on-the-eye-and-brain formulaic fantasy, comedy and violent action, the cinema of the ’80s actually reflected the complicated culture of its times; it was decidedly diverse, unquestionably interesting and assuredly surprising.

Here then, peeps, is the latest post in my series looking back at the most era-defining flicks of, well, their respective eras (see the ’60s and ’70s movie posts here and here) and it offers up the dectet of pictures – in no order but chronological – that sum up cinema of the 1980s. Word-up…

.

CLICK on the film titles for video clips (warning: bottom clip contains strong language)

~~~

Risky Business (1983)

For many, there’s no more ’80s a movie than Risky Business. And rightly so. Not only did it effectively augur how the entrepreneurial-driven, economically liberal culture of Reagan’s America would look onscreen, trailblazing the decade’s ostentatious and extravagant, MTV-friendly visual style (backed up by studio-rich, synthy pop music), but it also properly introduced to filmgoers Thomas Mapother IV, aka Tom Cruise. It tells the tale of a naïve, yet ambitious rich-kid (Cruise) who, while his parents are out of town, has an encounter with a hooker (the equally young and beautiful Rebecca De Mornay), then manages to total his dad’s car and come up with the ingenious/ dubious (delete as appropriate) idea of turning his home into a brothel for his horny schoolmates in order to pay for said motor’s repair. The plot sounds hokey, but thanks to a witty, knowing script and a lot of charm from its winning leads in star-making turns, as well as that aforementioned flashy and sexy, Miami Vice-esque look, the result is far from ropey. Many teen comedies would follow Risky Business in the ’80s, of course – hell, John Hughes built a Hollywood career on them – but none proved to be as significant (not least for unleashing The Cruiser on an unsuspecting world), smart, stylish and prescient as this flick.

~~~

WarGames (1983)

The computer geek. Nowadays they’re ten-a-penny in the movies, but before the early ’80s their celluloid presence was as thin on the ground as a ‘pooter game more advanced than Pong. That all changed with WarGames, though. Directed by the man who’d helmed Saturday Night Fever (1977), the versatile John Badham, it brought into the mainstream the notion of the ‘hacker’, an (often amateur) computer whizz who hacks into stuff they shouldn’t owing to their sheer bonce-bulging intellect and keyboard capabilities, thus potentially bringing about all kinds of unpleasant crap for us all. Given this was, as mentioned above, the era of Reagan (with all his neo-Con foreign policy wonks), the Cold War was once more hotting up and the threat of nuclear catastrophe was again looming large. Therefore, the sh*t-storm stirred up by the pubescent hacker in WarGames (played by Matthew Broderick, shortly to become immortalised as Ferris Bueller) involved accidentally inviting the US Government’s supercomputer to unleash hell on Mother Russia. As with Risky Business, the concept is pure hokum, but its execution is handled competently, ensuring the result is taut and thrilling in all the right places and – like many of Hollywood’s best flicks of the ’80s – satisfies as far-fetched escapist entertainment in all the others. The movie’s legacy, it could be said, is the glut of ‘pooter-based comedies that followed it, including everything from Electric Dreams (1984) and Weird Science (1985) to the Whoopi Goldberg vehicle Jumpin’ Jack Flash (1986). And just 12 short years later, in the shape of Toy Story, we’d get a movie every inch of which was designed by computer – as WarGames taught us, the dull, monolithic ‘pooter really was taking over, whether we liked it or not.

~~~

Ghostbusters (1984)

1984: the year of the ’80s Hollywood blockbuster. The evidence? That year, Beverly Hills Cop, Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom, Gremlins, Romancing The Stone, The Karate Kid and Police Academy were all released. Yes, all of ’em. Oh, and Ghostbusters, of course. One may argue that the latter is the ultimate ’80s Hollywood blockbuster; the ultimate, if you will, ’84 Hollywood blockbuster of ’84 Hollywood blockbusters. Why? Well, not only is it one of the decade’s biggest box-office hits (making nearly $300 million; over $600 million in today’s money); is bloody brilliant with so many memorable scenes and moments (Slimer’s take-down in the hotel; the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man climax and, well, every line Bill Murray utters); is fantasy adventure of the highest order like so many of that decade’s cinematic hits; effectively features the trademark 1980s city, the Big Apple, as one its main characters; and nailed its brand maximisation perfectly (Ray Parker Jr.’s infectious theme song and that unmistakeable title card logo), but it also marvellously married the hottest comedy properties of the time with Hollywood commerciality at its most creatively competent. For Murray, his co-stars Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis (who together co-wrote the flick) and John Belushi (the intended Peter Venkman, before his untimely death) were all weaned on the late ’70s/ early ’80s TV comedy phenomenon that was Saturday Night Live (1975-present) and/ or the project that would spawn the National Lampoon movie brand, with Ghostbusters proving the hit that sent them and the latter show’s reputation supernova. Hot young TV comedians and Tinseltown largesse, eh? Now that’s you call crossing the streams.

~~~

My Beautiful Laundrette (1985)

So what was going on in British film in the ’80s then? Well, by the middle of the decade, arguably not much. Aside from, perhaps, a handful of flicks financed by George Harrison’s Handmade Films – including Terry Gilliam’s excellent Time Bandits (1981) and Brazil (1985) – and experimental efforts from Peter Greenaway. As in the ’70s, the British film industry was suffering from a lack of finance and commercial success; flicks that caught the imagination of both the critics and the public were very few and far between. All that changed in ’85, though, with My Beautiful Laundrette. No British film of the ’80s managed to generate quite the same combination of freshness, of-the-moment urgency and controversy as this one. In 1982, Britain got a new terrestrial TV station, Channel 4, which admirably poured some of its money into a movie-making wing. Collaborating with a similarly new and progressive film company nattily entitled Working Title, it produced this flick, jam-packed full of polemical issues of the age: racism (Fascist whites versus Pakistani businessmen), homosexuality (the two male protagonists, one a young Daniel Day Lewis, lead a tentative but unashamed affair) and the politics of Thatcher’s Britain (entrepreneurialism versus education, unemployment, class and generational divides). Originally made for TV (admittedly it shows), the keenly observed, often comic piece was instead released cinematically and launched the careers of both its helmer Stephen Frears – who would go on to direct Helen Mirren to an Oscar in The Queen (2006) – and its Oscar- and BAFTA-nominated scribe Hanif Kureishi – who would go on to write the novel The Buddha Of Suburbia (1990) and its 1993 TV adaptation. To say My Beautiful Laundrette was a breakthrough is an understatement; to say it’s one of the most important films of the ’80s is unquestionable.

~~~

St. Elmo’s Fire (1985)

Unlike for the bright young things of a slowly re-energising British film industry, social realism wasn’t exactly the order of the day for Hollywood. Riding the revitalisation of US confidence and self-worth under good King Ronnie, Tinseltown instead banked on fantasy. Fairytale-esque adventures for both kids and adults – i.e. the original Star Wars trilogy (1977-83), the first four Superman flicks (1978-87), the Indiana Jones series (1981-2008) and Conan The Barbarian (1982) – was what the public wanted; not tales that tried to analyse issues of the day. Indeed, when Hollywood did turn to social realism in this era, it tended to produce something like St. Elmo’s Fire. Instead of being an American My Beautiful Laundrette, this coming-of-age drama about recently graduated young ‘uns – delivered by Joel Schumacher, who a decade later would churn out the dubious Batman sequels Batman Forever (1995) and Batman & Robin (1997) – was instead a vehicle for Hollywood’s new golden generation of actors, banded together by the media under the moniker ‘The Brat Pack’. To give it its dues, St. Elmo’s Fire does feature drug-taking, marriage and family break-up, unrequited love, idealism versus vocational pragmatism and a nervous breakdown, but frankly, with its one-dimensional characters and ropey dialogue, it plays more like a cartoon-cum-music video of post-campus life. It’s best remembered for its oh-so iconic cast (Demi Moore, Rob Lowe, Emilio Estevez, Ally Sheedy, Judd Nelson and Andrew McCarthy), its garish hairstyles and fashion, its chart-topping title song, John Parr’s St. Elmo’s Fire (Man In Motion), and one of the characters’ mode of transportation in the urban jungle, er, a jeep. In short, it’s all surface gloss and, thus, so ’80s it aches. The public gobbled it up at the time and it’s still eerily popular. And yet, for all that (or maybe because of it), to paraphrase one of its contemporary youth flicks, it somehow really is some kind of wonderful.

~~~

A View To A Kill (1985)

There was, mind you, one cinematic entity for which the UK and US film industries always converged – the doubling-up effort that was the big screen 007. Unfortunately, though, by now the ‘official’ James Bond film series, produced by movie dynamo Albert R. ‘Cubby’ Broccoli’s Eon Productions, was in a spot of bother. For the first time, Bond actually had competition at the flicks thanks to Hollywood’s latest love affair with action-driven fantasy adventure and, in particular, Indiana Jones. In no uncertain terms, the invention, pace, excitement and all-round quality of Indy’s first two adventures, Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981) and Temple Of Doom (1984), had stolen Bond’s thunder in the first half of the decade; agent 007, in the guise of the ever suave yet now 50-ish Roger Moore, was starting to look his age, his globe-trotting escapades less thrilling and less till-ringing at the box-office than they’d once been. That’s not to say the early ’80s Bonds For Your Eyes Only (1981) and Octopussy (1983) weren’t any good, but film fans – especially young ‘uns – seemed to be more excited by Harrison Ford being chased by a giant boulder or cutting a rope-bridge in half. In an effort to address this, Broccoli and co. did the only obvious thing they could with their next espionage spectacular (Sir Rog’s last) – embrace the 1980s. So, with A View To A Kill, what we have is an adventure mostly set in an American metropolis (San Francisco) full of flashing neon, fire trucks, Corvettes and police cars with wailing sirens; a plot that sees the villain (a peroxide-blonde Christopher Walken as a demented yuppie) and his sidekick (the crazy ’80s icon that is Grace Jones) wanting to blow up the home of the microchip, Silicon Valley itself, and best of all, the hottest music act of the day, Britain’s Duran Duran, delivering the title song. Did it work? Well, the profits were no higher than for the previous Bond, but the pop-tastic theme hit #2 in the UK charts and, even better, #1 in the States. Moreover, Moore himself got to bow out as 007 in the most ’80s Bond flick imaginable – his old-school smoothie gent colliding and, somehow, complementing the flashy aesthetic-driven world of the decade that taste forgot. Some Bond flicks merge into each other; this one stands out as brashly, colourfully and rather wonderfully as the Golden Gate Bridge in the Californian sunshine.

~~~

Jean de Florette/ Manon des Sources (1986)

Aside from for cineastes, foreign language cinema had never really properly broken through in Anglo-American culture. Yes, thanks to the media, many peeps had heard of Jean-Luc Godard, Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini, but how many in the US and the UK had actually seen one of their movies? All that, arguably, changed in the ’80s. In 1981, François Mitterand was elected French President and set about promoting the culture and history of the country by allocating financial support for films of which those were concerns. One such project that benefited was Claude Berri’s duology Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources, based on a novel by Marcel Pagnol. The latter, an established filmmaker, had actually adapted his own book for the screen back in the ’50s, but this production would pull out all the stops and take all the glory. With a combined budget making them the most expensive French film(s) made up to that point, they’re an archetypal example of ‘heritage cinema’ that the French government’s film funding made a trend of, their plot involving the inheritance of a farm in the Provence region around the time of World War One. Together they make for good viewing, but maybe except for a brilliant moment of tragic realisation on one character’s part, they deserve their place on this list for their success and legacy rather than their content. They were a huge hit in their homeland, both publicly and critically; moreover, while he’d been a massive star in France for years, it was this flick that finally made Gérard Depardieu a global name, as well as launching the career of his co-star Emmanuelle Beart. But most important of all was the flicks’ impact on the public abroad. In America Jean de Florette grossed a mightily impressive $5 million and in the UK – thanks too to the Peter Mayle book A Year In Provence (1989), later filmed as the Russell Crowe starrer A Good Year (2006) – the movies encouraged an increasingly moneyed middle class (yuppies very much among them) to holiday and buy property in Provence, eager to experience the beautiful countryside and idyllic culture so stunningly captured in the films. Yes, thanks to Depardieu and co., Francophilia had verily broken out, the symptoms of which (Brits in Provence, Gallic-themed TV ads and European film hits in the UK and US) have been with us ever since.

~~~

Beverly Hills Cop II (1987)

Judge Reinhold espoused in a documentary about Beverly Hills Cop II I saw recently (don’t judge) that, whenever he watches said movie in which he once starred, he’s amused by the size of the sunglasses every character wears. They’re big. But then, everything about Beverly Hills Cop II is big. By this stage in the ’80s, big was in for Hollywood; as it was everywhere else. Big hair, big shoulder pads, stereos so big they were called ‘ghetto blasters’ and big profits in business. Movies are Hollywood’s business, of course, so what was the best way for it to maximise profits? How about doing exactly the thing that made millions first time around all over again? How about making a sequel to every über-hit? The fast emerging suburban multiplexes were, by the end of the decade, awash with sequels to major blockbusters – Ghostbusters II (1989), Back To The Future II (1989), Lethal Weapon II (1989) and a third Indiana Jones (1989). Oh, and Beverly Hills Cop II, of course. The latter’s predecessor was huge at the box-office, featured an obligatory US #1 chart hit and became an instant comedy classic. To direct the sequel, producers Jerry Bruckheimer and the late Don Simpson turned to the helmer of their latest monster hit (the high-concept, high-octane, highly daft Tom Cruise starrer that was 1986’s Top Gun), Tony Scott. Having come to Tinseltown from the UK ad industry, Scott filled the movie with glossy, music video-like visuals and action set-pieces. This ensured the witty comedy that had so characterised the original took a back-seat; almost all of the film’s comic moments relying on star Eddie Murphy’s ad-libbing. It’s still a funny film, but only in places, and the comedy is definitely broader and swearier than the first’s. The plot, pacing and, well, overall quality are all rather ropey too, creaking under the weight of the need for the project to make major moolah. Unquestionably then, Beverly Hills Cop II fulfils that age-old movie sequel maxim: ‘the law of diminishing returns’. Still, given it, very impressively, made just shy of $300 million globally (only around $15 million short of the original’s total) and embraces every nuance of the ’80s’ garish aesthetic, for me it has to be the ultimate exponent of that decade’s addiction to the sequel – an addiction that, let’s be honest, has now grown into an epidemic. Thanks for that, the ’80s.

~~~

Wall Street (1987)

He’s been mentioned more than once in this post already and now it’s finally time to focus on the ’80s’ most enduring icon: the yuppie. In Gordon Gekko, Wall Street not only encapsulated one of the most recognisable stereotypes of its era, but also captured that era’s culture of aspiration, social-climbing, greed and excess brilliantly. In fact, this flick nailed all that so well that many seemed to regard it as an advert for the quick-buck banking crowd, rather than as the critique of Anglo-American economic liberalism hurtling along with nobody on the brake that it actually is. Wall Street, though, is far from a perfect film and maybe that’s why its point didn’t hit home as well as it might. As Bud Fox, a young stockbroker who’s seduced by the allure of easy money and the charismatic Gekko (Michael Douglas) who’s made a career out of making it, Charlie Sheen doesn’t really impress – he only ever seems one eyebrow-raise away from Hot Shots! (1991) – and Daryl Hannah as his trophy girlfriend is mis-cast. Plus, the screenplay, although it whizzes and crackles with impressive stock exchange floor-style dialogue and terminology, doesn’t quite put enough bones on its plot (a fight between two ‘fathers’ for the soul of Fox; the corrupt corporate raider Gekko and his own father, nattily played by Martin Sheen, an aircraft union man) to prevent the whole feeling a little twee. However, as noted, Wall Street was and always will be about Michael Douglas’s Gordon Gekko. An amalgamation of several real power brokers at the top of US business in the ’80s, the character is essayed expertly by Douglas, despite director Oliver Stone’s original reservations about casting him. The former rightly won an Oscar for his portrayal, the most memorable moment of which being the speech he makes to a room full of suits during which he utters the immortal phrase ‘greed is good’ (which was actually inspired by a pair of speeches given by two insider traders whose jailing sparked the film’s conception). In the years since the flick’s release, Douglas has confessed young stockbrokers have told him he’s the reason they joined their profession; perhaps a legacy he’s not too happy about. Especially given the fact Wall Street and Gordon Gekko were intended as a wake-up call – one that, in the midst of our current global economic crisis, some of us may wish we’d heeded.

~~~

Red Heat (1988)

Yuppies and big business are all very well, but there was another socio-political reality that loomed large over the decade too, namely the re-heating up and eventual burning out of the Cold War. Like WarGames, many US and UK flicks in the ’80s focused on the supposedly non-military conflict between East and West, whether they be espionage efforts (most of the Bonds, 1986’s Target, 1987’s The Fourth Protocol), comedies (1985’s Spies Like Us and Top Secret) or, well, just plain ridiculous (1984’s Rocky IV). The latter flick was an action-fuelled, mostly violent, rather sweary and utterly fantastical slice of so-bad-it’s-good cinema. Indeed, in the ’80s, Hollywood churned out so many of these sorts of films they became a sub-genre. And many can be referred to as Stallone or Schwarzenegger movies. Sly Stallone, naturally, was the star and driving-force behind the hugely, if inexplicably, popular Rambo and Rocky series. Arnold Scwarzengger’s list of flicks this decade were more varied. Sort of. He became a star playing the cyborg killing machine title character in James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984), then went on to mix fantasy, sci-fi and militaristic action heroics through the likes of Red Sonja (1985), Commando (1985), Raw Deal (1986), Predator (1987) and The Running Man (1987). All these complied with the Arnie movie template of violence, destruction and bad one-liners. And so did his next effort, Red Heat. However, the difference with this ‘un was it used the, by now, cooling off of the Cold War as a sub-text to its corny-as-popcorn plot. Schwarzenegger plays a captain in Moscow’s police militia who travels to Chicago to track down a Ruskkie crimelord and finds himself buddy-buddying up – à la 1987’s Lethal Weapon – with James (brother of John) Belushi’s wisecracking cop. The clever – and, yes, it is quite clever – twist to this dynamic, though, is that it’s Arnie’s hard-as-nails Soviet who’s the ruthlessly efficient half of the pairing; Belushi’s capitalist is the profane and world-weary one that seems to live just one level up from the villains he chases. Indeed, this is encapsulated by the gifts they exchange during the film’s denouement: Belushi receives Arnie’s expensive Swiss timepiece; Arnie gets Belushi’s crappy, second-hand wristwatch. Red Heat is a silly film, no question, but it was supposed to showcase how the coming end of the Cold War was breaking down barriers; a world in which America’s capitalist model had won and the US would rule the future as the single super power. But would that be the case? Did Red Heat‘s Arnie/ Belushi dynamic, in fact, ironically suggest things wouldn’t quite turn out like that, at least, for Hollywood? Well, peeps, that may be for another post…

~~~

Five more to check out…

Desperately Seeking Susan (1985)

Rosanna Arquette is mistaken for the ultimate ’80s pop star Madonna in this bright and breezy Big Apple set caper

Labyrinth (1986)

The 1980s David Bowie model (big, big hair and poptastic tunes) meets The Muppets – more or less – in a cult classic family fantasy

Crocodile Dundee (1986)

Australia hits it big by sending comic Paul Hogan’s Outback stereotype to New York

Rita, Sue And Bob Too! (1986)

More smart and witty social realism from Britain as a middle-class man pursues infidelity in Yorkshire suburbia

Working Girl (1988)

Hollywood turns the Big Apple business world into an aspirational romantic comedy, with Melanie Griffith, Harrison Ford and Sigourney Weaver along for the ride

~~~

… And five great movies about the ’80s

The Last Days Of Disco (1998)

Kate Beckinsale and Chloë Sevigny’s young professionals cling on to the dying disco era in early ’80s Manhattan

Billy Elliott (2000)

Outstanding Cinderella-story about a disadvantaged boy who realises he can realise a dream during the ’84 Miners Strike

Das Leben der Anderen (The Lives Of Others) (2006)

Espionage-themed drama that focuses on the preservation of humanity in the face of the Stasi’s (East German secret police) tyranny

This Is England (2006)

No-holds-barred but, in places, funny and entertaining account of a the conversion of a Falklands War victim’s son to the UK National Front Fascist movement

Micro Men (2009)

Made-for-TV recreation of the battle for the British home PC market between Amstrad’s Sir Clive Sinclair and Chris Curry’s Acorn Computers

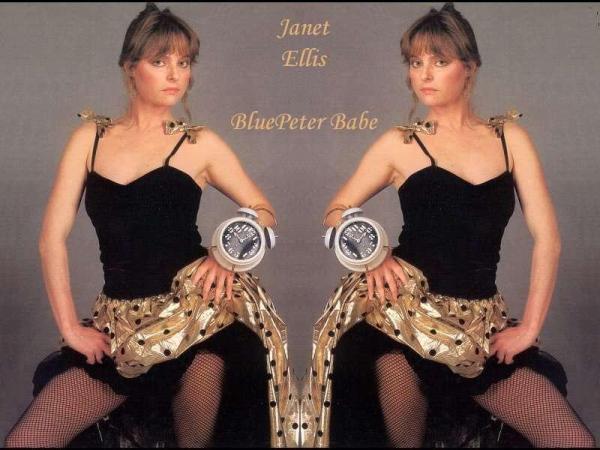

Janet Ellis/ Sarah Greene: Blue Peter Fitties

Talent…

.

… These are the lovely ladies and gorgeous girls of eras gone by whose beauty, ability, electricity and all-round x-appeal deserve celebration and – ahem – salivation here at George’s Journal…

.

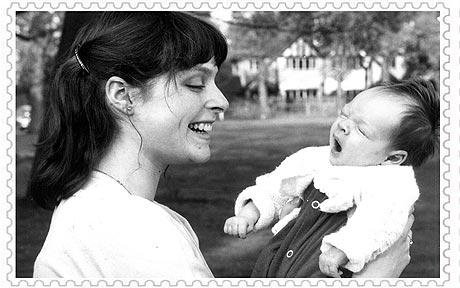

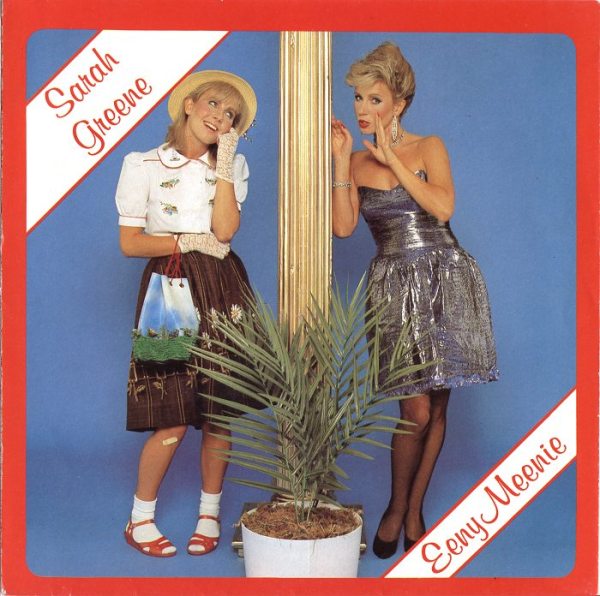

A children’s telly-tastic totty one-two for October – yes, it’s surely the two most desirable belles ever to have graced the old Television Centre Blue Peter studio, Janet Ellis and Sarah Greene. Individually, they lit up drab weekday early-evenings as they gave us history and geography lessons, baked cakes, interviewed celebrities and presented to us ‘something they’d made earlier’; together, they’re simply 1980’s TV deities – and both still look terrific today. Here they are then, the latest couple to enter this blog’s Talent corner…

.

Profiles

Names: Janet Ellis/ Sarah Greene

Nationalities: English

Professions: TV presenters/ Actresses

Born: Janet – 16 September 1955, Kent/ Sarah – 24 October 1958, London

Known for: Janet – presenting classic BBC1 children’s magazine programme Blue Peter (1958-present) for four years (28 April 1983 – 29 June 1987), during which time she achieved fame and acclaim for setting a new women’s European freefall record with the RAF after breaking her pelvis in training, as well as announcing to the nation in November ’83 that the Blue Peter garden in the grounds of BBC Television Centre in London’s Shepherd Bush had been vandalised. Before Blue Peter, she appeared as Teka in the 1979 Doctor Who story The Horns Of Nimon and on the puppet-driven kids’ show Jigsaw (1979-84). Mother of three children, one of whom is pop star Sophie Ellis-Bextor/

Sarah – pre-dating Janet as a Blue Peter presenter (19 May 1980 – 27 June 1983), having been given the job at just 22 years-old; then the youngest ever. After her stint, during which she memorably dived to the wreck of the Mary Rose, she moved on to host BBC1’s lively Saturday morning magazine show Saturday Superstore (1982-87) alongside DJ Mike Read and then to co-host its replacement Going Live! (1987-93) with Phillip Schofield and Gordon The Gopher. Like Janet, she also appeared in a Doctor Who story, as Varne in Attack Of The Cybermen (1985), as well as starring with Michael Parkinson in the hoax paranormal drama Ghostwatch (1992) and competing in the 2008 series of Dancing On Ice (2006-present). Plus, in September ’88 she was famously involved in a helicopter accident with fellow TV personality Mike Smith, whom she married the following year.

Strange but true: Janet was happy for a very young Sophie Ellis-Bextor to appear on Blue Peter several times with her (proving the rumour that the former had to leave the show owing to giving birth to the latter out of wedlock to be untrue), while in 1983 Sarah released a pop single named Eeny Meenie.

Peak of fitness: Janet – taking a soaking in a Blue Peter feature dressed only in Victorian underwear/ Sarah – appearing in a one-piece swimsuit on Brighton beach and pier for Blue Peter.

.

.

CLICK on images for full-size

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Holly hits 50: how Breakfast At Tiffany’s came to the screen and changed everything

Good golly, Miss Holly: Audrey Hepburn as the irrepressible, irresistible Holly Golightly in Breakfast At Tiffany’s – perhaps the signature role of her delightful, unforgettable career

Blogs are supposed to be sources of personal opinions, assertions and divulgences, so perhaps it’s time I offer you up a confession, folks. And here it is. I was 19 years-old and in my first year of university: fashionably, I had a poster on my wall of Jennifer Aniston; unfashionably, I fell hopelessly in love with Audrey Hepburn. And the latter had absolutely everything to do with my very first viewing of Breakfast At Tiffany’s (1961).

Like it had for so many peeps before and has for many more since, that movie and the angelic Audrey in the titular role of Holly Golightly utterly bewitched me. I must have watched my recorded-from-the-TV VHS version of the film God knows how many times over the next year or two. It’s a wonder that, like I had as a 10 year-old with my tapes of The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and Moonraker (1979), I didn’t wear it out. But why did I fall for it so?

Well, there’s the look; the cool, glamorous yet breezy early ’60s interpretation of Manhattan it features. There’s the contrast of sunshine and heartbreak in the atmosphere it conjures up. There’s the smooth, jazzy score from Henry Mancini that also offers the dreamy, sad signature tune Moon River. There’s the wit, sass and warmth of the script, delivered so wonderfully by a cast including Patricia Neal, Martin Balsam, Buddy Ebsen and George Peppard (whose so-called writer character I so identified with – and still do). And, as said, above everything else there’s Audrey; beautiful and kooky, jubilant and sad, innocent and worldly-wise Audrey with her ginger cat with no name (aside from ‘Cat’, of course).

In hindsight, as a romantic, oft melancholic 19 year-old already in love with the movies and with a penchant for the oh-so cool feel of the early ’60s, it was inevitable I’d fall hook, line and sinker for Holly and co. Yes, me and Breakfast At Tiffany’s; it was kismet.

Truman’s blues: Capote with Audrey Hepburn (and husband Mel Ferrer) (l) and Marilyn Monroe (r) – although friends with both, he far from approved of the former’s casting over the latter

Years later now, I must admit it’s no longer my favourite film. People move on and wistful students grow up. It still holds a fond place in my heart, don’t get me wrong, but it no longer feels like ‘my film’. In fact, since I was that 19 year-old I’ve come to realise in just how many hearts Breakfast At Tiffany’s holds a fond place; just how popular a flick it is – and just how big an impact on popular culture it’s had in its 50-year existence. For, yes, that’s right, this year – in fact, officially last Wednesday (October 5) – Breakfast At Tiffany’s celebrated a half-century since it was first released in cinemas.

But, unlike much in the movie, its journey to the screen was neither sophisticated nor carefree. In 1958, American writer Truman Capote – who would achive great acclaim with the murder-themed ‘non-fiction novel’ In Cold Blood (1966) – authored a novella named, yes, Breakfast At Tiffany’s. It told the tale of a free-spirit named Holly Golightly, who has run away from a marriage in the Dust Bowl to Manhattan’s Upper East Side and earns her keep as (in the words of Capote himself) an ‘American geisha’. Set in the early 1940s and told from the point-of-view of a homosexual, Capote-like observer, it boasts glamorous and faux yet believable characters and drips with atmosphere and melancholia.

Drawn from the author’s own experiences of growing up in Manhattan and, to some extent, people he knew, Breakfast At Tiffany’s first featured in the November ’58 issue of Esquire magazine and went on to be published in book-form with three Capote short stories. Readers quickly drew comparisons between Holly Golightly and Sally Bowles from Goodbye To Berlin (1939) by Capote’s mentor Christopher Isherwood – the character who would later be immortalised by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret (1972), the musical film adaptation of the latter work. Nevertheless, Capote’s tale struck a chord with both critics and the public (contemporary Norman Mailer hailed him: “the most perfect writer of my generation… [I] would not have changed two words in Breakfast at Tiffany’s”), ensuring it became a hit and Hollywood was soon interested in giving it the big screen treatment.

Capote sold the rights to Paramount Pictures and knew what he wanted from the eventual movie. First of all, he was adamant who should play his (anti-)heroine. In the novella, Holly Golightly is an 18-19 year-old; as much an inexperienced teenager as a worldly young woman. She has a hard, flinty-like exterior too, but underneath is so vulnerable it feels she could be snapped in two at any moment. For Capote then, the ideal casting for her would be none other than Marilyn Monroe. Looking at it that way, it makes perfect sense – indeed, Marilyn was actually another influence on Capote’s realisation of Holly. And it seems Paramount had no objections to the idea, so much so they hired scriptwriter George Axelrod – who had written the Monroe-headlined films The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Bus Stop (1956) – to tailor a script specifically for her.

“Paramount double-crossed me in every conceivable way. Holly had to have something touching about her – unfinished. Marilyn had that. Audrey is an old friend and one of my favourite people, but she was just wrong for that part.’’ ~ Breakfast At Tiffany’s author Truman Capote on the casting of Audrey Hepburn instead of Marilyn Monroe as Holly Golightly

However, this idea was fast to hit the buffers, not least because, well, that’s exactly what poor old Marilyn was doing. The demise of both Monroe’s movie career and her life are infamous – almost every film fan knows that her last completed flick was The Misfits (1960) and just how difficult a shoot that was owing to her personal troubles. In actual fact, though, the specific reason why Monroe didn’t take the role was because she was advised against it by her acting guru, the legendary coach Lee Strasberg. He opined that playing a character who was, however you dressed it (or her) up, a prostitute would be very much the wrong step at this stage in her career.

The film’s producers then, Martin Jurow and Richard Shepherd, needed someone else – and it was now that they turned to Audrey Hepburn. Ironically, given how iconic a role in her canon it would become, she wasn’t interested at first. Like Monroe, and you couldn’t really blame her, she wasn’t crazy about playing a hooker. But the producers persisted, telling her that that’s not who Holly was; she was really a ‘dreamer of dreams, a lopsided romantic’. Audrey wasn’t convinced by the director they’d chosen either, as she hadn’t heard of him. In an effort to please her they instead hired Blake Edwards, helmer of recent knockabout submarine comedy hit Operation Petticoat (1959), which had starred Cary Grant and Tony Curtis. The director they’d let go was, in fact, John Frankenheimer who, now free, would instead go on to make two Hollywood classics, Birdman Of Alcatraz and The Manchurian Candidate (both 1962).

In the end, Jurow and Shepherd got their girl. According to a book published this year, Breakfast at Tiffany’s: The Official 50th Anniversary Companion, by Sarah Gristwood, Blake Edwards himself flew out to Switzerland to charm Audrey. Gristwood writes: “Edwards joined Hepburn’s husband, her agent and even her mother in convincing her that the style he would use to shoot the picture would effectively purify the part”. Unsurprisingly, at the news of this casting, Capote got the mean reds. Or just saw red. But, from his point of view, it would only get worse.

As mentioned, in the novella the character of Paul ‘Fred’ Varjak, the sensitive narrator who becomes fascinated with Holly, was most definitely a gay man. For their film version, the producers cast a rising actor, the handsome, strong-jawed George Peppard, who was most definitely not a gay man. It was pretty obvious then, this being the early ’60s, the film version of Paul would be heterosexual – plus, it turned out, a love-interest for Holly. Moreover, a pivotal character in Capote’s book was a bartender named Joe Bell; right or wrong, Joe didn’t make the cut for the movie at all. It must have become increasingly clear to Capote that Jurow and Shepherd really had no intention of filming a faithful adaptation of his book.

.

Still, filming got underway, but it too wasn’t without its problems. Unfortunately, the off-screen chemistry between Hepburn and Peppard was, well, off. It wasn’t that they disliked each other, which nobody has ever suggested they did, but that their approaches to the project clashed.

Audrey had always and would always be an actress of spontaneity and intuition; she was neither trained nor particularly intense in her methods (although she had experienced her fair share of intensity, such as an absent father, two miscarriages and growing up in Nazi-occupied Holland). She was a supreme comedy actress, gifted with perfect timing and an infectious, natural sparkle. Conversely, Peppard was trained and – at least at this early stage of his career, years before he became Colonel John ‘Hannibal’ Smith in TV’s The A-Team (1983-87) – took his craft seriously. If anything, he saw his role as the movie’s main character. But while Paul/ ‘Fred’ is often the audience’s point of reference and arguably the central character, it’s patently clear who the star of Breakfast At Tiffany’s is and, thus, to whom the main role belongs. And it ain’t George Peppard.

Filming was complicated further when the important first scene, over which the opening titles play and which critically dramatises the movie’s title, proved surprisingly difficult to capture. For this was in spite of the fact that its location (outside Tiffany’s jewellery store on Fifth Avenue in the heart of Manhattan) enjoyed an unexpected traffic lull at the precise time the cast and crew had rolled up for filming. Unfortunately, controlling the large crowds who’d turned up to watch, a crewman’s near electrocution in a freak on-set accident and, yes, Audrey’s dislike of pastry (Holly eats a pastry snack along with sipping a coffee as she gazes into Tiffany & Co.’s window) all combined to test the relatively green Edwards’ directorial chops. However, the scene was of course captured and now is revered and recalled as one of the flick’s best loved moments (see video clip above) – full of bittersweet, almost irresistible appeal thanks, in no small part to the theme of Moon River playing over the top of it.

Incidentally, Edwards chose not to use Manhattan locations for every exterior scene – who knows, maybe because of potential crowd-control difficulties. While most exterior shooting did make use of real Manhattan locales (such as the outside of Holly and Paul’s Upper East Side apartment building), the scene in which Audrey and George look for Cat (the film’s final scene), as well as the one in which Audrey sits on a fire escape strumming her dinky guitar as she sings Moon River (probably my favourite of the entire movie; see bottom video clip) were filmed at Paramount’s studio lot in Hollywood, as were the vast majority of the movie’s interior scenes. In fact, even some of the scenes supposedly set inside Tiffany’s – when Holly and Paul visit the store on their day out around New York – were also filmed at Paramount.

Putting on a brave face?: Peppard and Hepburn joke on-set (l), but their opposing approaches led to difficulties for Blake Edwards, whose face (r) suggests the challenge the shoot was

With its somewhat challenging shoot complete, Breakfast At Tiffany’s now needed to find its sound. And, let’s be honest, in the hiring of Henry Mancini as composer, did it ever.

It was Edwards’ choice to bring Mancini on board owing to the former’s previous success in coming up with the memorable theme tune for TV show Peter Gunn (1958-61), on which Mancini had actually worked with the former (the two, of course, would combine again on the highly popular Peter Sellers-starring Pink Panther film series). A protégé of jazz great Glenn Miller, Mancini was always going to go down the jazz route with Breakfast At Tiffany’s. And the score he delivered for the movie perfectly reflected its on-screen smooth urban sheen and sometimes sentimental, other times off-beat feel. Indeed, listen to the theme from the film actually entitled ‘Breakfast At Tiffany’s’ in the video clip below; it’s light, wispy, smooth, cool and uplifting, as well as – although it’s not Moon River – instantly recognisable.

And then, of course, there’s Moon River. The piece of music for which Breakfast At Tiffany’s itself will always be most recalled, it’s the film’s unofficial theme, as well as that of its protagonist, Holly Golightly. Mancini’s tune is complimented by pitch-perfect lyrics by singer and songwriter Johnny Mercer, who actually provided three separate sets of lyrics for the project – the adopted lyrics being chosen by Mancini as best fitting Audrey in the title role, given they seem to refer to the loss of her character’s brother Fred (her ‘huckleberry friend’) and hope for a future better than the present with someone special (‘we’re after that same rainbow’s end, waitin’ round the bend’).

The song has become a firm favourite with the public, having been covered by over 90 artists over the years, but Mancini always felt the best version was recorded by the person for whom it was written: “No-one else has ever understood it so completely [as Audrey Hepburn did]. There have been more than a thousand versions, but hers is unquestionably the greatest.” Bizarrely, prior to the film’s release, Paramount wanted to remove the song from the soundtrack, only for Audrey to exclaim: “Over my dead body!”.

“A movie without music is like an aeroplane without fuel. Your music has lifted us up and sent us soaring. Everything we cannot say with words or show with action you have expressed for us. You have done this with so much imagination, fun and beauty. You are the hippest of cats – and the most sensitive of composers!’’ ~ Audrey Hepburn in a letter to composer Henry Mancini about his film scoring of Breakfast At Tiffany’s

In the end, all the difficult, hard work paid off. Breakfast At Tiffany’s was a big box-office hit – the seventh biggest of its year in the US, in fact, where it made around $14 million; $1 million more than the legendary wartime adventure The Guns Of Navarone (1961).

And the critics lapped it up as much as the punters. On its release, Time magazine recognised that as an adaptation of Truman Capote’s novella, the movie certainly sanitised its story and characters, but that wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, opining that “for the first half hour or so, Hollywood’s Holly (Audrey Hepburn) is not much different from Capote’s. She has kicked the weed and lost the illegitimate child she was having, but she is still jolly Holly, the child bride from Tulip, Texas, who at 15 runs away to Hollywood to find some of the finer things of life — like shoes.”

Meanwhile, in reviewing the film, The New York Times called it a “completely unbelievable but wholly captivating flight into fancy composed of unequal dollops of comedy, romance, poignancy, funny colloquialisms and Manhattan’s swankiest East Side areas captured in the loveliest of colors”.

Moreover, the movie proved a magnet for award nominations. For her performance as Holly, Audrey was nominated for an Oscar for Best Actress, a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy and a David di Donatello (Italian film industry) Award for Best Foreign Actress; Blake Edwards was nominated for the Directors’ Guild of America award; George Axelrod’s script was nominated for an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay and won the Writers’ Guild of America (East)’s award for Best Written American Drama; and, most notable (and maybe most deserved) of all, Henry Mancini won Oscars for both his score and – along with Johnny Mercer – for Moon River (Best Original Song), along with a Grammy for the score.

.

But it’s really over the years since the mere months after its release that Breakfast At Tiffany’s has enjoyed the popularity and acclaim to which so many of us today are familiar. The movie’s acquisition of the oh-so enviable status of ‘Hollywood classic’ wasn’t an overnight thing; like a rolling stone gathering gold dust rather than moss, it took decades for it to be perceived rightfully as the celluloid nugget it is. And, quite frankly, that’s really down to fashion – but in two very different ways.

First, relatively soon after its release and for years afterwards, the genre of the Hollywood romantic comedy and, thus, Breakfast At Tiffany’s itself, was out of fashion. As noted in these two previous posts on this blog (1 and 2), Tinseltown’s output during the ’60s and ’70s went through dramatic changes to reflect the shifting social attitudes and issues of the times. ‘New Wave’-informed, counter-culture efforts and hard, gritty dramas steeped in neo-realism became the order of the day, leaving out in the cold the urbane and sophisticated, but generally pretty innocent rom-coms that’d had made hay in the preceding years. Filmmakers still made romcoms, of course – indeed, Woody Allen scored Oscar-winning success with Annie Hall in 1977 – but such high points tended to be few and far between and, if anything, attempts to revise the genre.

One may argue then, it wasn’t until the end of the ’80s that cinemagoers and, therefore, Hollywood fell back in love with the romcom, thanks to the huge commercial and critical success of When Harry Met Sally… (1989). Full of wit, sass and fine byplay between its two leads like the very best of the genre of old, this was the perfect modern updating of the romcom and fittingly set its female star Meg Ryan off on a career driven by similar fare, as if she were, well, the ’90s Audrey Hepburn.

Indeed, from then right up until now, multiplexes have been bulging with romantic comedies and inevitably yesteryear’s very best efforts such as the Cary Grant/ Katharine Hepburn starrer Bringing Up Baby (1938), the Doris Day/ Rock Hudson-headlined Pillow Talk (1959) and, yes, Breakfast At Tiffany’s have been rediscovered and are happily en vogue once more.

Thoroughly modern Hollies: Natalie Portman in Givenchy’s original Holly Golightly dress for the Harper’s Bazaar September 2006 issue (l), Zooey Deschanel advertising Oliver Peoples sunglasses in summer 2009 (m) and Anne Hathaway in a Vogue November 2010 shoot (r)

In actual fact, despite its modern adoration, the rediscovery of Breakfast At Tiffany’s has resulted in more negative examination of it, owing to one of its characters, than other classic romcoms. And rightly so really. Conceived as knockabout light-relief, the interpretation of Holly’s Japanese neighbour Mr I Y Yunioshi by Hollywood legend Mickey Rooney as an affected Oriental stereotype, complete with a prosthetic mouthpiece, has unsurprisingly fallen foul of modern PC opinion.

I can’t deny I’ve always felt rather awkward watching his moments in the film – by today’s standards the portrayal of the character certainly seems misguided. However, Rooney has maintained that until relatively recently he was aware of no criticism, claiming that whenever he met an Asian-American they had nothing but praise for the role, yet the criticism of today has stung him and he’s said had he been aware people would be offended, he would never have done it. Both Blake Edwards and Richard Sherpherd have admitted regret over the portrayal too.

All the same, this very specific criticism hasn’t seriously impacted on the resurgence of Breakfast At Tiffany’s. And, in no small part, that’s doubtless due to the other reason the movie’s modern popularity can be put down to fashion. And, by fashion, this time I literally mean fashion.

Nowadays, you’d have to be a Buddy Ebsen-style Doc Golightly not to be aware of the fact that Audrey Hepburn is revered as one of the biggest – if not the biggest – of history’s style icons. And her fond place in the hearts of fashionistas the world over owes a vast amount to Breakfast At Tiffany’s. Yes, it’s a film that plays around with the glamorous image that Manhattan projected in the early ’60s and, of course, features the jewel at the heart of the high street diamond business that is Tiffany’s & Co. itself, but the flick’s fashion credentials most of all rest on Audrey’s shoulders in the shape of the garment that rests on her shoulders in that unforgettable opening scene, namely that little black dress.

“[Audrey Hepburn] didn’t go to acting schools, she didn’t hear the word Strasberg, she did not repeat in front of the mirror. She was just born with this kind of quality and she made it look so unforced, so simple, so easy.” ~ legendary Hollywood director Billy Wilder fundamentally disagrees with Emma Thompson on Audrey Hepburn’s acting talent

The creation of legendary French fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy – who first decked out Hepburn in her second Hollywood flick Sabrina (1954) and became firm friends with her thereafter – it was specifically requested as Holly’s night-time dress-up best by Audrey herself and made it into the film after some slight alterations (including the removal of a long slit that would have revealed a great deal of leg) by costume designer Edith Head. A mainstay of modern, elegant female fashion, the ‘little black dress’ is as unavoidable an item of today’s world as the laptop, the alcopop and the hoodie – and, while its origins date back to Coco Chanel’s design from the 1920s, Holly Golightly’s is undeniably one of the most important.

As if to underline that fact, on December 5 2006 (following its modelling in Harper’s Bazaar magazine by Natalie Portman; see image above), one of the original dresses produced for the film was auctioned at Christie’s in London and reached an astonishing £467,200 (US$923,187) – more than six times its asking price. The money raised went to a charity to build a school in Calcutta, India.

But it’s not the dress on its own. Images of Audrey from Breakfast At Tiffany’s (especially those in which she wears the dress and has Holly’s over-long cigarette holder plonked in her mouth) have nowadays become so popular they’re positively iconic. You can buy not just prints of such images, but handbags, wall clocks and mouse pads adorned with them. It’s as if those images, the film and Audrey herself have become the same entity: chic style at its absolute zenith. Indeed, so ubiquitous has the whole thing become that it seems not a year goes by when one of Hollywood’s starlets jumps at the chance to recreate the Audrey/ Holly look – the Portman image and those of Zooey Deschanel and Anne Hathaway above are merely some of the latest. Indeed, you need only look on the ‘Net to see how far the cult of all things Holly-cool has spread: want to get as close as possible a pair of Ray-Bans to those Holly wears? Check these out… want a bathtub-come-sofa just like hers? Check this out… And so on and so forth…

And yet, fashion is, of course, just surface gloss; there’s much more to Breakfast At Tiffany’s than just how it – and Audrey in it – looks. For, though the movie may be 50 years-old, it’s an ageless concoction of cool, off-kilter, romantic, melodic charm that peeps from practically every demographic have fallen for, just as they have for its leading lady. Capote may not have approved, but millions of Holly and ‘Cat’-lovers certainly do. And, well, who am I kidding? I haven’t really moved on that far and, deep down, I’m still that wistful 19 year-old student – there’s little of me that doesn’t still love the film and its star player. Because me, Audrey and Breakfast At Tiffany’s; it was kismet. And always will be.

Playlist: Listen, my friends ~ October 2011

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or have never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and enjoy…

CLICK on the song titles to hear them

.

The Rolling Stones ~ Under The Boardwalk

Johnny Rivers ~ Secret Agent Man

Yes ~ Every Little Thing

Aretha Franklin ~ Bridge Over Troubled Water

Alice Cooper ~ No More Mr. Nice Guy

John Denver ~ Annie’s Song

John Lennon ~ Beef Jerky

Andrew Gold ~ Lonely Boy

U2 ~ October

Murray Head ~ One Night In Bangkok

Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley ~ Theme from Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple

Fleetwood Mac ~ Big Love

Bruce Willis and The Temptations ~ Under The Boardwalk

.

The regeneration game: the story behind the changing faces of Doctor Who

Eleven ages of a man: the undectet of Doctors – in chronological order (and from left to right), William Hartnell, Patrick Troughton, Jon Pertwee, Tom Baker, Peter Davison, Colin Baker, Sylvester McCoy, Paul McGann, Christopher Eccleston, David Tennant and Matt Smith

So then, aside from kicking-off the first proper autumn (or, for all you North Americans out there, fall) month of the year, I take it you know what tomorrow will be bringing us? That’s right, the climactic concluder to the latest season of the indubitably genius Doctor Who. Yes, with all the trailers on the box and the fevered anticipation all over the ‘Net, it’d take a Silurian condemned to the far reaches of the Universe not to know that in one day’s time The Doctor must come up with surely his greatest ever victory – cheating his own death. And his proper death at that, with no chance of a regeneration.

How on earth’s he going to do it? Good question, given we’ve all seen it happen already (at the start of the season – ‘timey-wimey’ and all that). Still, on the bright side, we do know he will manage to cheat death, as it’s been announced that the current actor in the role (Matt Smith) will remain in place for at least another two years yet. Phew, ne-c’est pas? Anyway, talking of The Doctor’s ability to regenerate, in this very post allow me, in celebration of this season’s climax, to guide you through a glimpse at his previous regenerations; that is, in layman’s terms, the on-screen moments when the TARDIS keys have passed from one Doctor actor to the next…

WATCH the video at the end of the post to see, one after another, The Doctor’s regenerations

~~~

The First Doctor (William Hartnell) → The Second Doctor (Patrick Troughton)

The Tenth Planet (1966)/ The Power Of The Daleks (1966)

At the end of the final episode of the serial The Tenth Planet, The Doctor appears to die owing to exhaustion and general old age. Indeed, earlier in this serial he’d commented to his current human companions Ben Jackson and Polly that his body was ‘wearing a bit thin’. In reality, it was actor William Hartnell himself who was wearing a bit thin. Finding it difficult to get on with the show’s new production team (following the moving on of now legendary, but then young and ambitious, producer Verity Lambert) and often unable to remember his lines (owing to an undiagnosed onset of anteriosclerosis), Hartnell’s time had come – the showrunners had decided it was necessary to replace him. But how? Doctor Who was a huge hit in the early-teatime Saturday slot, so there was no question of ending the series with Hartnell’s departure, so just how could they introduce a new actor in the same role? The answer was genius – and it came thanks to then script editor Gerry Davis and then producer Innes Lloyd. Davis reasoned that as The Doctor was now well established as an alien and not human, it would be quite acceptable for him not to die when he appears to do so… indeed, his body would in fact undergo a process of ‘renewal’. And, cannily, Lloyd pointed out that if and when they wanted to replace the lead actor in the series again, they could use this excuse once more. Thus, before the eyes of a transfixed nation, William Hartnell’s Doctor ‘renewed’ himself and became Patrick Troughton’s younger Doctor. Originally, the actual transformation wasn’t intended to be caught on-screen, but vision mixer Shirley Coward realised she could transpose the image of Troughton’s face on top of Hartnell’s – much better than having Hartnell cover his face with his cloak as he ‘died’ then have it pulled back to reveal Troughton, which was the original idea. And, even better, halfway through the transition, the image was overexposed causing the screen to fade almost entirely to white, while the TARDIS time-travel sounds and other eerie noises could be heard; the notion was that this psychedelic ‘renewal’ of the Doctor would be similar to a bad LSD trip, as was discovered last year by the release of archive BBC notes on the subject. Yes, really. Indeed, Billy Hartnell’s Doctor may have been an irascible old traditionalist, but in the end he had far more in common with the hippie-infused culture of the Swinging Sixties than he surely would ever have thought.

~~~

The Second Doctor → The Third Doctor (Jon Pertwee)

The War Games (1969)/ Spearhead From Space (1970)

His may be a hugely popular incarnation of The Doctor with today’s fans, but back in the day Patrick Troughton’s take on the character unfortunately coincided with a dip in viewing figures for the show. By the end of the ’60s, it appeared the public simply wasn’t as crazy for Doctor Who as it had been in the middle of the decade. A change needed to be made then, but in actual fact it was Troughton who decided to step down from the role, as opposed to the showrunners asking him to do so. After three years, like Hartnell before him, the actor found the schedule of filming between 40 and 45 episodes a year was too much, plus he was concerned by potential typecasting. Fortuitously, his decision suited the Beeb and the producers as, between them, they came to the conclusion that cost constraints would be imposed on the now seemingly less popular show. What was the effect of this then? Well, at the end of Troughton’s final serial, the excellent The War Games, as punishment for continuously meddling in the lives of other lifeforms, The Doctor would be banished by his own Time Lord race to a single planet – Earth. Yup, no more elaborate, expensive, studio sets for Doctor Who; exterior filming in country villages and interiors in easily mocked-up offices and manor houses would be the order of the day for the next incarnation, the dandy dynamo that was Jon Pertwee. And yet, for all that, one concession, arguably a real improvement, was made – six months after Troughton’s Doc had bowed out, whirling about and gargling away into a monochrome void (presumably at the beginning of his latest ‘renewal’), he reappeared as Pertwee’s Doc falling out of the TARDIS and into a wood… in colour. Yes, with the BBC leaving behind old black-and-white and embracing all the colours of the rainbow at the start of the new decade, The Doctor’s early ’70s adventures may have been completely Earth-bound, but thanks in no small part to their new colourisation, they once more struck an enormous chord with kids of all ages up and down the nation.

~~~

The Third Doctor → The Fourth Doctor (Tom Baker)

Planet Of The Spiders (1974)/ Robot (1974)

In establishing his Doctor as a heroic, if patrician, dapper man of action, Jon Pertwee’s was surely the most popular incarnation thus far, yet after four years in the role he decided to move on. Just as William Hartnell’s had been before him, his decision was in part influenced by the fact that colleagues with whom he’d been comfortable on the show had left or would soon be leaving the programme, specifically producer Barry Letts and co-stars Katy Manning (who had played his long-time companion Jo Grant) and Roger Delgado (who had originated The Doctor’s Time Lord adversary character The Master and had tragically died in 1973). In looking for a replacement, the outgoing Letts saw the British fantasy film The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad (1974) and was impressed by Tom Baker’s performance as the villain. Although it was intended The Fourth Doctor would be played by an older actor, the 40-year-old Baker won the part and, of course, absolutely made the role his own. His portrayal – all unpredictability, curly hair, boggling eyes and crazily long scarf – took the show to new heights and new viewers, not just in the Britain of the ’70s, but also in the US where Baker’s episodes were the first to be shown in syndication. To this day, for the majority of TV viewers his is surely the most identifiable interpretation of the Gallifreyan gallivanter. The baton was passed from Pertwee to Baker, in the presence of classic companions Sarah Jane Smith (Elisabeth Sladen) and Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart (Nicholas Courtney), at the end of the episode Planet Of The Spiders, in which The Doctor saves the day but sacrifices himself when he contracts radiation poisoning, and at the start of the next episode Robot, in which the audience witnesses the completion of the actor handover; Baker confusedly spouting lines of previous Doctors and dressing up in different guises (including a Roman soldier) before settling on his Aristide Bruant-inspired togs that’d become his trademark. One further point of interest: it was during this change-over that the transformation of one Doctor into the next was first referred to on-screen as a ‘regeneration’.

~~~

The Fourth Doctor → The Fifth Doctor (Peter Davison)

Logopolis (1981)/ Castrovalva (1981)