007/ 50: “My name’s Bond, James Bond” #3 ~ the four years of three Bonds (1969-73)

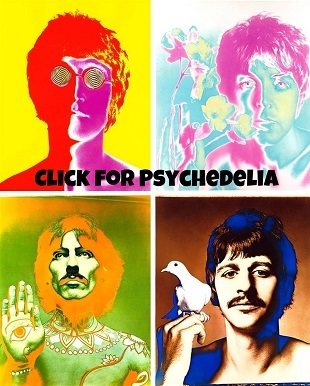

Trio of heroes: the casting of Connery in Diamonds (l), Lazenby in Majesty’s (m) and Moore in The ‘Die (r) is a tale of reluctance, resignation and reignition, but who won and who lost?

What would you do if your little boy kept on throwing tantrums and wouldn’t play with his hollowed-out volcano sets and cool toy gadgets anymore? Ditch him and get a new one, right? Well, surely for right rather than wrong, the real world doesn’t work like that. But the world of the cinematic Bond does. For when the actor who played James Bond throughout the 1960s wanted out, producers Albert R Broccoli and Harry Saltzman didn’t blink; they let him go and hired someone new. Having said that, though, perhaps the world of the cinematic Bond does work like that, because after just one film they actually went back and re-hired their original actor (all right, someone else replaced him again after just one further film, but still).

Yes, between 1969 and 1973 – surely one of the most culturally and socially transformative periods of the 20th Century – the Bond films went through a white-knuckle Louisiana Bayou speedboat ride of change the like of which it’s never experienced since, for in a space of just four years, three different actors played the main man himself, our man Bond. And this blog post, peeps, the latest in celebration of Blighty’s finest‘s big 50 this autumn (and more specifically the third of four looking at the casting of 007) tells that very story, one that’s as intriguing, engaging, surprising and colourful as any plot of an actual Bond film.

Sick and tired of playing a character that, by the end of the stratospherically successful and fun but stratospherically OTT You Only Live Twice (1967), had become more robotic than dramatic, 007 actor Sean Connery had severed his ties with Eon Productions’ Bond film series. In all fairness, as big a reason as the latter was the effect it was having on his downtime from Bond – the intense media intrusion had become just too much; during the filming of Twice he’d even been followed into the loo by an over eager Japanese journalist. In which case, the two-year lead up to the next Eon effort On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) began with the search for the next James Bond. And, from the off, it was as media-fixated and public-aware as Connery’s private life.

Rumour suggests that two familiar names were in the running to slip on the shoulder-holster next. Apparently, Saltzman was keen on travelling to Cambodia to adapt The Man With The Golden Gun with Roger Moore as 007; this didn’t happen (not least because Moore was still committed to playing TV’s The Saint), but of course Golden Gun would eventually get made as his second flick in the role. What certainly seems true is a young Welsh classically-trained actor who’d just made his big screen debut in the acclaimed The Lion In Winter (1968) was considered by Broccoli and Saltzman. But, believing himself too young for the role, the 22 year-old Timothy Dalton took himself out of the running. His chance though, like Moore, would come again…

.

.

In the end, the opportunity to fill Connery’s Conduit cut suit was whittled down from around 400 hopefuls (also apparently including future TV Sherlock Holmes and co-star in 1964’s My Fair Lady, Jeremy Brett) to a shortlist of just five: Englishmen Anthony Rogers and John Richardson, American Robert Campbell, Dutchman Hans de Vries and Australian George Lazenby. Like Connery had been back in ’62 before being cast in Dr No, they were all relative (and, in some cases, complete) unknowns.

Out of the five, Richardson probably boasted the most screen experience, having had lead roles opposite Honey Ryder herself Ursula Andress in She (1965) and Raquel Welch in One Million Years B.C. (1965), while Rogers had played Sir Dinadin in the cinematic adaptation of musical Camelot (1967), had acted opposite John Wayne in El Dorado (1966) and had essayed an alien in five episodes of TV’s Doctor Who. For his part, de Vries had actually appeared in the previous Eon Bond effort You Only Live Twice as a control technician and, sort of ironically, in the Sean Connery-starring western Shalako (1968). Conversely, Campbell seemingly was without a major credit to his name. New to the acting game too – and maybe the least experienced of the five – was Lazenby. And, somewhat surprisingly, after all five wannabes were screen-tested, it was the latter who won the role.

Hailing from New South Wales and a bit of a ‘larrikin’ (a bit of a lad, Aussie-style) while growing up, Lazenby had come to London in ’63 and, while working as a car salesman in Park Lane, had been spotted by a talent scout and quickly hired as a model. His most high-profile work during this time came on TV, though – as a grinning chap holding on his shoulder a box of Big Fry chocolate in a commercial. And yet, in spite of having practically no acting experience and certainly no thespian training, his casting as Bond was arguably no accident – at least, from his point of view.

Knowing full well that the 007 role was open, the 28 year-old Lazenby decided to pursue it. Cannily, he a bought a suit from the Saville Row outlet used by Connery that the star had ordered but not collected, as well as acquiring a Rolex Submariner watch (the model worn by 007 in the films), had professional photos taken of him in Bondian poses around London wearing both and, having found out who Broccoli’s barber was, booked an appointment to get his hair cut at the exact time he knew the producer would be there. Amazingly, his efforts paid off – Broccoli offered him an audition.

Five down to one: the grandstand media event that was the casting of the new James Bond in 1967 led Life magazine to devote an entire article to the final five, (clockwise from top right) Anthony Rogers, George Lazenby, Robert Campbell, John Richardson and Hans de Vries

And apparently what eventually swung Lazenby the Bond gig was a swing – at a stunt co-ordinator during a mock fight-scene in the screen-test, with the auditonee landing one on the guy’s nose. Impressed then by Lazenby’s physical prowess, as well as his physique, handsome features, swagger and (no doubt) Connery-modelled look, Broccoli and Saltzman decided they’d got their man. But, as has become legend, from now on it was a bumpy ride at almost every turn.

The trouble seems to have stemmed from that fact that, no doubt due to his larrikin nature and an oversized, youthful ego, Lazenby felt because he’d been cast as Bond he was now a star and behaved as such on the film’s set. Broccoli, Saltzman and the film’s helmer Peter Hunt very much felt otherwise – Lazenby had to earn his stripes to become a star; he had to prove himself a success as Bond first. Not only did his attitude rub up the producers the wrong way, but apparently owing to friends of his hanging around the set now and again, Hunt became riled and thus the two went through phases of not being on speaking terms, far from an ideal situation for a lead actor and director to find themselves in.

At the time, the UK press too tried to stir up the idea there was a rift between Lazenby and his leading lady Diana Rigg (well known for having played Emma Peel on TV’s The Avengers) when a reporter overheard her telling her co-star she’d been eating garlic ahead of a love scene to be filmed in the afternoon – apparently she had said it to Lazenby in jest. However, in a BBC interview with Rigg last year, she did admit to Lazenby’s behaviour being a difficulty on-set and his inexperience dooming him from the start (he also even managed to anger M actor Bernard Lee by playfully chasing him while on a horse).

And weeks before the flick opened in December ’69, Lazenby announced to the world he’d decided to move on from Bond already (see video clip above). Thanks to dubious advice from his agent Ronan O’Rahilly and his own assertion that as Anglo-American cultural changes of the time had forced Hollywood to embrace ‘New Wave’ in order to ‘connect’ with the youth (examples being films such as 1969’s Easy Rider and Midnight Cowboy), Bond’s days on the silver screen were numbered. He turned up at the premiere of Majesty’s with a fashionable if very un-007 long hairstyle and beard and announced: “Bond is a brute, I’ve already put him behind me. I will never play him again; peace – that’s the message now.”

.

Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile

- Years after On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, George Lazenby ‘enjoyed’ another brush with Bond when he cameoed in TV movie The Return Of The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (1983), dressed in a tuxedo and driving an Aston Martin DB5 with the number plate ‘JB007’

- Nearly a decade before Live And Let Die, Roger Moore guest-starred in an espionage-themed sketch on UK variety star Millicent Martin’s TV show Mainly Millicent (1964-66) as one ‘James Bond’

- Despite being good mates off-screen, Connery and Moore have never appeared together on the big screen, although they have both starred opposite their great mutual friend Michael Caine – Connery in classic adventure The Man Who Would Be King (1975) and Moore in madcap comedy misfire Bullseye! (1990)

Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile

.

But just two years later and in the midst of a stalled acting career (aside from Bond, he’s been most notable for appearing in the 1990s-filmed Emmanuelle soft porn sequels), he apparently appealed to Broccoli and Saltzman to cast him again in the role for the next effort Diamonds Are Forever; unsurprisingly, they didn’t acquiesce. Eventually, in 1992 he admitted in an interview with US TV’s Entertainment Tonight: “I was so naïve, so green. I was a country boy from Australia, basically, who walked into the Bond role.” For his part, Peter Hunt opined before his death in 2002 that Lazenby was “a great looking guy [who] moved very well. I think if things had gone the other way, he would have gone on to be a very good Bond”.

The next man cast as 007 certainly didn’t ‘walk into the Bond role’, for he was the chap who’d walked out on it just two or so years before. Unimpressed with Majesty’s grosses (although it was the #1 film at the UK box-office in its year, it didn’t quite pull in the mega bucks like the Bond epics before it, especially in America), studio backer United Artists put pressure on Broccoli and Saltzman to do all they could to re-cast Connery as Bond. This, rather amazingly given the gruff Scotsman’s very negative recent attitude to the role, they eventually managed to do for Diamonds – but not before checking out other options first.

There’s perhaps no better proof that Diamonds is a very ‘American’ Bond film than the fact a US actor was so strongly considered for 007 the producers offered him a contract (which he accepted and, thus, had to be paid in full when Connery was eventually cast). Yes, that’s right, unthinkable today it may be but an American almost became Eon’s James Bond. Who was he? The middling famous John Gavin, whose most recalled performance is as Janet Leigh’s boyfriend in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Surprisingly another yank was also considered, namely Adam West, who was much more famous for playing ’60s TV’s Batman (1966-68), while now legendary Brit thesp Michael Gambon was apparently in the running too, although he quickly ruled himself out.

In the end, though, when United Artists chief David Picker informed Broccoli and Saltzman that Connery must be hired whatever the price, it seems they caved. And the price turned out to be high, nay astronomical – a cool $1.25 million (£20 million in today’s money). But that wasn’t all; as part of his deal, Connery was assured United Artists would fund two further movies of his choice. One was the Sidney Lumet drama The Offence (1971), which turned out to be rather the box-office turkey, and the other a version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth to both star Connery in the title role and be helmed by him, yet this one wasn’t even made as UA backed out when learning Roman Polanski was filming an adaptation (also 1971). Undaunted, though, Connery put his inordinately high fee to good use – with it he helped set up the Scottish International Education Trust, an initiative to fund promising Scottish artistes so they’d stay in the old country. Alex Salmond would have been very proud.

.

.

And yet, despite the unprecedented deal struck to entice him back into ‘Bondage’, it seems the Big Tam actually enjoyed himself making Diamonds. Not only did he ensure he got much of the afternoons off to play a round of golf, he also appeared to make the most of being in Las Vegas – he was quoted in a July ’71 article of Montreal Gazette saying: “The first week [of filming] I didn’t get any sleep at all. We shot every night, I caught all the shows and played golf all day. On the weekend I collapsed – boy, did I collapse. Like a skull with legs”.

During the Amsterdam leg of filming he appeared to be in good spirits too (see video clip above), while at the time he went on record that he approved of the movie’s script (no doubt owing to Tom Mankiewicz’s über-witty dialogue rather than the plotting) and apparently he especially enjoyed the company of one of his co-stars – years later Lana Wood (Plenty O’Toole) admitted that they’d had a discreet affair during filming.

In the end then, one might even wonder why Connery knocked – at least Eon’s – Bond on the head after Diamonds (he’d return to cinemas in 1983 in ‘rival’ 007 production Never Say Never Again)? Well, perhaps a make-up man who was also quoted in the Montreal Gazette piece, while holding the toupée he’d just removed from Connery’s bonce, had the answer: “You know, I sometimes think that the reason he doesn’t want to do any more Bond pictures is that he hates this bloomin’ thing so much”. Who knows…

Just a handful of months after the release of Diamonds, Broccoli and Saltzman were tasked with finding another actor to portray their hero – yes, the third in four years. This time, though, he’d be neither contentious nor inexperienced, nor would he require a toupée despite actually being born three years before Connery. However, Roger Moore apparently wasn’t the absolute shoe-in to slip on the shoulder holster in Live And Let Die (1973) that legend might suggest.

.

Back in the swing and bright young(?) thing: Connery enjoys himself on the ‘moon’ set of Diamonds Are Forever as Terry O’Neill snaps him playing golf (left), while Albert R Broccoli and Harry Saltzman pose with their new star Roger Moore while filming Live And Let Die (right)

Rather unbelievably, the two producers seemed happy to consider United Artists’ rather illogical desire to see an American star fill the role this time out (names UA bandied about are supposed to include Burt Reynolds for sure and maybe both Paul Newman and Robert Redford) by approaching Clint Eastwood. The latter, though, saw sense immediately and told Broccoli and Saltzman only a Brit should play the part – see, Clint’s a sensible chap if he’s not on a stage and there’s an empty stool next to him.

English thesps whom apparently tested for the role include Jeremy Brett (again), Simon Oates and John Ronane (who?), familiar UK TV face William Gaunt, Julian Glover (who’d go on to play Bond villain Kristatos in 1981’s For Your Eyes Only) and perennial ‘possible 007’ of this era Michael Billington (who would play Ruskkie spy Sergei Barsov in 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me).

In the end, though, it appears Roger Moore was head and shoulders above the crowd; in fact, according to his 2008 autobiography My Word Is My Bond, so sure was he that he stood a good shot, he stepped away from his cult TV adventure drama The Persuaders! (1971), co-starring Tony Curtis, after just one series. However, it wasn’t entirely plain sailing prior to filming. Apparently Saltzman phoned Moore to tell him Broccoli felt he should lose some weight, then Broccoli phoned him to tell him Saltzman felt he should get a haircut – to be fair, they both had a point, especially Saltzman; Rog couldn’t have sported his Swinging Sixties-esque Persuaders! barnet as Bond.

But following the experience they’d gone through with Lazenby, Broccoli and Saltzman as well as – and in particular – The ‘Die‘s director Guy Hamilton were clearly sagacious in selecting their new Bond and how they introduced him to the world. Hamilton took the smart step of ensuring this 007 (unlike poor George’s ’69 model) didn’t do ‘Connery Bond’ things in the latest film. Thus, watch The ‘Die again and you’ll neither see Moore’s Bond here wearing a tuxedo and bow-tie nor will will you hear him order and drink a ‘shaken not stirred vodka Martini’ (actually, he wouldn’t do that until his third film The Spy Who Loved Me). So ingrained into the identity of the cinematic 007 was it, mind, that the inevitable introduction ‘My name’s Bond, James Bond’ was a line he couldn’t escape from uttering; although in his autobiography he admits he may have been conscious of trying not to do it this with a Scottish accent.

.

.

With time it became abundantly clear, though, that the filmmakers had chosen very wisely. Not only did The ‘Die turn out to be a box-office giant (of all 22 of them thus far, it’s still the third biggest Bond film in cinema takings – inflation adjusted – while its premiere on British TV in January 1980 remains the most watched movie broadcast in UK television history, but it also set up a long and, certainly compared to the Connery years, happy marriage between Eon and their lead actor.

Moore would go on to play 007 in six further flicks, of course: The Man With The Golden Gun (1974), The Spy Who Loved Me, Moonraker (1979), For Your Eyes Only, Octopussy (1983) and A View To A Kill (1985). Some may say that when his era entered the ’80s he went on in the role too long. Fair dues, maybe in hindsight he did. But maybe he didn’t.

His combination of more than effective light-comedy and convincing action-man credentials made for a Bond that was an utterly unflappable, debonair gentleman jet-setting around the world and preventing megalomaniacs from destroying it, with a raised eyebrow here, an innuendo there and many notches on the bedposts everywhere. Together with Broccoli (without Saltzman after Golden Gun), he capably and very stably guided the series through 12 years; for an entire generation he is simply their James Bond.

But every dog – or lucky devil of a dog, as Sir Rog’s Bond was – has its day. And following the release of A View To A Kill and at the age of 58, absolutely rightly Sir Rog had his, hanging up his shoulder holster for the last time. One of the biggest, if not the biggest, roles in all cinema was up for grabs again, so who would claim it this time? Well, it’s a tale as twisty-turny and unlikely as Octopussy‘s plot and one I’ll tell in a future post (the last in this particular series) that’ll come shooting towards you like a ‘007’ bullet from Scraramanga’s golden gun some time soon, peeps…

.

Wheel of fortune?: the spoof James Bond adventure Casino Royale – and first film adaptation of Ian Fleming’s original novel – was a chaotic if luxurious affair, but did it make cinema tills ring?

If you’re at all like me and have ever bothered to sit through 1967’s Casino Royale, the so-called comedy pastiche of all things Bond, you probably concluded as soon as its closing credits, well, closed that that’s two-and-a-bit-hours of your life you’re never getting back. But, again, if you’re at all like me you may also have wondered after watching said flick, just how on earth such a star-packed, dazzlingly looking and beautifully scored, but most of the time incredibly crap, and yet at other times rather amusing grand disaster of a movie ever got made in the first place? And how, coming practically slap bang in the middle of the mid- to late ’60s ‘Bondmania’ of the Connery 007 era, it fared at the box-office?

Well, if you have pondered on those puzzlers, peeps, then dare I say it, this (the latest effort from George’s Journal to mark Blighty’s finest‘s 50th anniversary year) is verily the blog post for you. Just how did this first big-screen effort to offer up another actor to Connery as Bond (actually many of them) come to the screen – especially when the ‘official’ Bond movie people appeared to own the rights to Fleming’s novels as thoroughly as 007 owns the bragging rights when it comes to pulling? And just what did the public make of it? Were they delighted, bemused (like most of us nowadays) or simply disinterested?

So, first things first: it was all Ian Fleming’s fault. Were it not for the uncoordinated manner in which he sold away the rights to adapt his Bond novels into films, Casino Royale would never have been made – at least not by the producer whose ultimately bloated and disfigured baby it was, Charles K Feldman. For it was this one-time Academy Award-nominated producer who brought this flick to cinemas, not James Bond’s regular film chiefs, producers Albert R Broccoli and Harry Saltzman of Eon Productions.

These two had acquired the rights to turn every one of Ian Fleming’s Bond novels into movies when the latter bought them from the author in 1961 and the former teamed up with him to form Eon a few months later. However, as part of this deal, Fleming hadn’t sold them the rights to his very first novel, the breakthrough book that introduced the world to James Bond, 1953’s Casino Royale. That was because three years earlier they’d found their way into Feldman’s mits. Exactly how isn’t important; what is important is Feldman had landed the rights and come the mid-’60s set about filming the book – indeed, filming it as a rival Bond movie to the four highly successful ones Broccoli and Saltzman had by now made.

.

.

Whatever you think of the movie that was eventually churned out, don’t let it discolour your opinion of Charles K Feldman’s career prior to this notorious venture, because it was stellar. Originally a talent agent for Hollywood royalty such as John Wayne, Claudette Colbert, Lauren Bacall and director Howard Hawks (indeed, legend has it that it was Feldman who got Bacall’s debut role bumped up in Hawks’ classic 1946 Humphrey Bogart-starring noir The Big Sleep, a move that made her an instant star), he went on to produce the classics A Streetcar Named Desire (which, of course, made Marlon Brando a total star and got Feldman his Oscar nom), the 1955 Marilyn Monroe comedy The Seven Year Itch (the one with that subway grille scene) and the madcap bedroom farce What’s New, Pussycat? (1965), which co-starred Peter Sellers, Woody Allen, Peter O’Toole and Ursula Andress.

Of all the movies he’d made, it was this latter effort – a big hit notwithstanding – that certainly more than any other pointed the way for what Casino Royale would become. Not only would Casino Royale share those four stars (among all of those it features) mentioned above with What’s New, Pussycat?, but the Swinging Sixties-informed, often crazy and utterly rompish tone of Pussycat could be said almost to be a precursor of Royale‘s. Not just that, but the fact that the former was initially a vehicle for its original writer Warren Beatty (its title apparently was the phrase Beatty used when answering the phone – how very ’60s) and it turned into a project re-written by Allen to such an extent that Beatty jumped ship/ was forced out completely, may well be a sign of the circus Royale would become just a couple of short years later.

Not that Feldman ever intended Casino Royale to turn into a cowboys and Indians-crashing and performing seals-featuring circus, of course – in fact, at the outset his intention was not to make a comedy at all, but adapt the book straight. Just one year after the novel’s original publication, the American TV network CBS had purchased its rights from Fleming and immediately had made an adaptation – so, yes, James Bond first appeared on-screen (the small screen, that is) as early as 1954 (see middle video clip below). The hour-long Casino Royale (Climax!) telly drama wasn’t a success, though; not least because it was filmed live, but also because it rather bizarrely switched around the nationalities of the British Bond and his American sidekick Felix Leiter, ensuring the first screen actor to play the iconic hero was Californian Barry Nelson (although Bob Holness, future host of cult ’80s UK gameshow Blockbusters, had already played the character on British radio – yes, really).

And yet, all this hadn’t deterred Feldman; he was sure that if adapted right, Casino Royale could be a big-screen success. In the late ’50s, he turned to Oscar-winning screenwriter Ben Hecht to have a whirl at a few script drafts. Ironically, as with the ’54 TV version, Hecht’s first attempt retained much of the novel’s content but replaced the British Bond with a card-playing American gangster. Subsequent drafts saw Bond return, but also the gambit that the name ‘James Bond’ is passed on to different agents as a sort of codename to confuse his enemies. For wrong rather than right surely, this idea made it all the way through to the final film, but another Hecht notion that ‘Bond’ escapes from a German brothel disguised as a lesbian mud wrestler did not. Quite frankly, it might as well have done.

Boom and bust: David Niven endures an explosion – figurative as well as literal? – at the start of the film (l), while Joseph McGrath tries to direct Peter Sellers as Jacqueline Bisset looks on (r)

Apparently, in 1966 Time magazine was reporting Hecht had departed the project and the script had been completely re-written by legendary auteur Billy Wilder. Whether that was merely Hollywood tittle-tattle, who knows; similarly, rumour has had it that Catch-22 (1961) author Joseph Heller also contributed to the script. What is true is the flick’s three credited screenwriters would turn out to be Wolf Mankowitz (whom ironically had introduced Broccoli to Saltzman back in ’61 and had written early drafts of their first Bond effort, 1962’s Dr No), former blacklisted Hollywood scribe Michael Sayers and UK comedy writer John Law (whom among other things had penned the all-time classic ’66 Frost Report sketch ‘Class’, which had seen John Cleese, Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbert represent Britain’s three classes by standing in line according to their varying heights).

Filming of the movie took place during much of 1966 and, clearly contributing to the almighty mess that was the finished product, was bizarrely chaotic. In the same Time article that had claimed Wilder had worked on the script (a multi-page colour spread on the movie, in fact), star David Niven had admitted: “it’s impossible to find out what we’re doing”. He may have meant that it was impossible for anyone working on the flick to find out what was actually going on. Feldman’s approach to try and better the Broccol-Saltzman Bond efforts was to offer the audience more… and then more and more again and yet more.

Clearly a snowball effect took over, ensuring that not only did the filming process become a seemingly out-of-control Hollywood Frankenstein-like horror monster (Frankenstein does actually feature in the film at one point), but also the budget trumped up by studio backer Columbia Pictures (ironically the financial backers of the Eon Bond today, although they’re now owned by Sony) doubled; it was originally $6million and the end $12million. In this manner at least, Casino Royale bettered the other Bonds – Thunderball (1965) had cost just $11million and You Only Live Twice, released just months after Royale, was a relative snip at $9.5million.

So where did all the money go? Some of it definitely on the cast. As mentioned, Niven, Sellers, Allen and Andress all feature, but so too do Hollywood legends Orson Welles, Deborah Kerr, Jack Holden and John Huston, as well as Swinging Sixties ‘It Girls’ Joanna Pettet, Daliah Lavi, Barbara Bouchet, Angela Scoular and Jacqueline Bisset. There are also cameos from Jean-Paul Belmondo, George Raft, as well as top Brit comedy performers Bernard Cribbins, Anna Quayle and Ronnie Corbett and, in-jokily, Eon Bond alumni Vladek Shebal (Kronsteen in 1963’s From Russia With Love) and Burt Kwouk (Mr Ling in 1964’s Goldfinger and, of course, Cato in the Pink Panther film series).

.

Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile

- Straight after working on Casino Royale, one of its directors Ken Hughes was hired by Broccoli and Saltzman to helm their classic musical adaptation of Ian Fleming’s children’s book Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968)

- One of Casino Royale‘s many female distractions, Angela Scoular became a ‘bona fide‘ Bond Girl just two years later when she was cast as one of Blofeld’s ‘Angels of Death’, Ruby Bartlett, in ‘official’ series entry On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969)

- Casino Royale cast member Terence Cooper (who plays the agent that becomes ‘James Bond’ owing to his ability to sexually attract any woman he meets) was considered for the the real thing in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service – only for George Lazenby to land the gig

Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile

.

As if this incredibly impressive, nay bizarrely diverse, cast couldn’t be cajoled into performing by one helmer alone, the film instead used of half a dozen (hey, at least there’s still less of ’em than there were on-screen Bonds). To be fair, Feldman probably found it necessary to hire so many ringmasters not because of the largeness of his cast, but because of the largesse of the circus threatening to explode out of his big-top. With constant changes of artistic direction and supposed daily re-writes of scenes, no one director could have directed this flick. Enduring the filming process must have been like witnessing the nightmarish development of the final alien in this summer’s Prometheus, a hybrid pulling in inspiration and ideas from all over the shop – Hollywood genre in-jokes, spy-fi satire, moddish nods and psychedelic visuals (sometimes all of them in the same scene).

For what it’s worth, cast member John Huston mostly directed the film’s opening (the scenes at the stately home of Niven’s stately Sir James Bond and McTarry’s Scottish castle with Deborah Kerr); Val Guest directed many of the scenes with Woody Allen (which unsurprisingly were penned by Allen himself) and additional ones with Niven to try and link the whole film together; Ken Hughes (whom Broccoli and Saltzman had originally considered as helmer for Dr No) directed perhaps the film’s wittiest and best bit, the Berlin scenes with the Twiggy-like Pettet; between them Robert Parrish and Joseph McGrath directed the scenes featuring Sellers, Andress and Welles; and, uncredited, stunt arranger Richard Talmadge co-directed the utterly bananas climatic battle at ‘Casino Royale’ itself.

The most legendary leg of the filming, thanks to its referencing in Roger Lewis’s biography The Life And Death Of Peter Sellers (1995) and its pseudo-screen adaptation of 2004, is that which involved Peter Sellers. Cast as Evelyn Tremble, a genius baccarat player enlisted by Niven’s real 007 to smash SPECTRE agent Le Chiffre (Welles) at the gaming tables while assisted by espionage mercenary Vesper Lynd (Andress), Sellers initially invested all his enthusiasm in the project, seemingly seeing Tremble (yet another fake Bond but in the film’s only ‘real’ bit of Fleming adaptation) as the opportunity he’d wanted all his career to play a dashing heroic lead. This then explains why Sellers’ acting seems inexplicably to veer from the slapstick (cavorting on a bed with Andress in costume as Hitler, Napoleon, Charlie Chaplin and Toulouse Lautrec) to the serious (playing it straight in the casino scenes and zealously knocking out an immigration official at an airport like a Bond-esque hard-man).

Whatever aspirations Sellers had for his involvement in the film pretty much went out the window, though, when his involvement became sporadic. A troubled chap and thus an unreliable performee, Sellers’ relationship with Welles quickly turned sour; the scene at the gaming table they share had to be filmed in two parts as neither would act opposite the other. And when Sellers realised the film – or his section of it – was turning into a comedy/ was always supposed to be a comedy (who knows which?) he both started re-writing his own lines and hired Terry Southern to do so it would play straighter. In the end, he totally severed links with the flick and a demise for his character had to be hastily put together from bits already filmed – the strange LSD-esque nightmare sequence in which he’s tortured by Le Chiffre and finally ‘shot dead’ by Vesper. Ironically, it’s one of the most engaging and dramatically satisfying of the entire movie.

.

.

Planned for release at Christmas ’66, Casino Royale finally made it on to screens four months later on April 13 1967. And, after the chaos that had been its production, this date proved far from unlucky for Feldman’s folly because , relatively speaking, audiences of the time actually lapped it up. Sure, Royale was no hit in the league of the Eon Bonds of the mid- to late ’60s (surely it would have been a fantastic achievement, nay a miracle, had it turned out to be), but in grossing about $42million at the box-office – around $283million in today’s money – it was far more than a modest financial success, in spite of its enormous budget. Moreover, not only did hit the #1 spot at the US box-office during its run (see middle image below), but also finished 13th in the list of the highest grossing movies in North America for 1967 – by comparison, the ‘official’ 007 effort that year, You Only Live Twice, finished in seventh place.

So why was it a genuine success and not the utter failure many for decades have assumed it must have been? Part of the reason has to be its marketing. Publicised honestly as something of a Swinging Sixties romp (complete with a body-painted girl à la Andy Warhol on the poster), it was also sold on the line that it was the ultimate Bond film, boasting more girls, more villains, more stunning visuals, more outlandish scenes and, yes, more Bonds than ever before. It simply was ‘more more‘ than the masses had yet seen in any Bond film; in fact, it arguably still is.

In marketing the movie this way, Feldman and his Columbia cohorts were shamelessly hitching a ride on the back of the ‘Bondmania’ phenomenon, of course, which unquestionably must have helped pull in the punters (i.e. it was a film that featured ‘James Bond’, therefore people would go on and see it. But the raison d’être of the finished film was to send up the whole Bond thing that had developed into/ fed an entire spy-fi sub-genre anyway, so technically it could have delivered something of a cinematic surprise or twist for filmgoers expecting a straighter ‘Bond film’. The filmmakers then, if challenged, may well have happily defended the shameless publicity linking it to Eon’s Bond bandwagon given such ‘artistic merits’.

But surely there was more to the film’s success than marketing and the Bond brand – dare one say it, but perhaps the film itself played a role too? There’s no getting away from it, Casino Royale is a car-crash of a movie. But, to spin out that metaphor further, at times it genuinely feels like a pile-up of Rolls-Royces and Bentleys. For the vast majority of the time, it looks fantastic. Unquestionably, one the major reasons why its budget spiralled upwards in the way it did was because of the truly impressive sets designed by Michael Stringer.

From the ridiculous to the sublime: despite the presence of both sky-diving Red Indians (l) and Frankenstein (r) in its climax, Casino Royale still hit the #1 spot at the US box-office (m)

Often they’re opulent (with Western aristocratic iconography, including at one point real lions), sometimes deliriously psychedelic (full of swirling pinks and oranges and blues and greens) and other times they brilliantly aid the pastiche (the darkly jagged look of the Berlin spy school wonderfully apes the iconic look of 1920’s classic horror The Cabinet Of Dr Caligari). In short, Casino Royale‘s visuals are an unforgettable tour de force.

Not just that, though, for the movie also sounds terrific. Hiring the composer he’d used for What’s New, Pussycat? again proved one of Feldman’s canniest moves on Casino Royale (you may argue there isn’t much competition there given his other decisions, but hey). For the meloldic meastro that is Burt Bacharach, whom rightly was white-hot property when it came to popular music in the ’60s, hit Royale‘s score absolutely out of the park.

Bacharach’s combining of campy, old British music hall-style themes for the moments of high parody and, well, ludicrousness (an example being the film’s fine title theme played by Herb Alpert’s Tijuana Brass – a chart hit – and sung at the end by Mike Redway) with lush, luxurious, romantic melodies that perfectly compliment the opulent look of the movie (listen to the film’s Oscar-nominated and now classic love theme, The Look Of Love, performed by original singer Dusty Springfield in the clip below) worked a total treat. It’s almost worth sitting through the movie for its music alone. Almost. Well, all right, sort of.

And, even if few of today’s film fans have done so, many a film critic back in the day certainly sat through Casino Royale. While some were unsurprisingly far from won over by what they witnessed (Roger Ebert described it as ‘possibly the most indulgent movie ever made’; Variety decried its lack of ‘discipline and cohesion’), others – admittedly the minority – have over the years somewhat reassessed the flick. At Bright Lights Film Journal (Brightlightsfilm.com), Robert von Dassanowsky claims it’s ‘a film of momentary vision, collaboration, adaption, pastiche, and accident. It is the anti-auteur work of all time, a film shaped by the very zeitgeist it took on’, while Allmovie.com reviewer Andrea LaVasseur even heralds it a ‘psychedelic, absurd masterpiece’.

But what do I, deep down, think? Well, folks, you’ll just have to read for yourself when I come to review the flick itself as the first in the next instalment of my ongoing ‘Bondathon‘. For, yes, in the words of Mike Redway, don’t fear, James Bond is here… and here to stay for some time yet at George’s Journal…

.

.

007/50: Designing 007 ~ Fifty Years Of Bond Style at The Barbican (until September 5)

Man(nequin) and motor: Bond’s iconic Aston Martin DB5 and a mocked-up Sean Connery in his classic grey suit from Goldfinger welcome visitors, but does the exhibition have a midas touch?

If I was that talented Scottish thesp Alan Cumming then I’d buy the full-scale model of him in the guise of the roguish ‘pooter nerd Boris Grishenko that features in The Barbican’s Designing 007: Fifty Years Of Bond Style exhibition (and which was used in the 1995 film GoldenEye when the character has just been frozen solid by exploding liquid nitrogen tanks). Why? So I could put it in my lounge and whenever I come home from a heavy night on the tiles look at it and consider, whatever state I’m in, I’ve always looked worse. I’m not Alan Cumming, though, but if I had a lot more spare cash than I do, I’d still definitely buy that model, plus many more things from this exhibition, for the simple reason they’re utterly iconic and, what’s more, they ensure this exhibition itself is an unqualified success.

Just to clarify, you can’t buy anything that’s on show here – they’re much too special. Bond’s Walther PPK and passports of the character in various actors’ guises? Oddjob’s steel-rimmed bowler hat from Goldfinger (1964)? Jaws’ teeth from The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and Moonraker (1979)? Tee Hee’s metal arm and claw from Live And Let Die (1973)? Models of the Lotus Esprit from Spy and the Q-Boat from The World Is Not Enough (1999)? The torture chair from that same movie? And Francisco Scaramanga’s golden gun from, er, The Man With The Golden Gun (1974)? Yes, they’re all on show. All of ’em. As is much more besides.

And yet it’s not just the breadth of this exhibition (which itself is considerable) that impresses, it’s the design of it too. Much thought, effort and no little money has gone into the way the space offered up by The Barbican is used to showcase all this stock that’s featured in all 22 Bond epics brought to us by film company Eon Productions across a remarkable half-century. Yup, its curators (aided by the not inconsiderable input of 1990s and 2000s Bond film costume designer Lindy Hemming) have done a fine job.

Having passed the frankly brilliant opening gambit of a Connery mannequin leaning against a battleship grey Aston Martin DB5 (complete with correct Goldfinger number plates and would-be tyre-slashers), you enter the exhibition, which kicks off with a room simply titled ‘Gold’. This unsurprisingly is themed around that most precious of materials that has quite the association with the world of 007 and his films – and works as a loose testament to the iconic legacy and thus mass success of the movie series, introducing the engaging and well executed props-and-audio-visual mixture of content that continues throughout the rest of the exhibition.

Dressed for success: the exhibition’s ‘Casino’ room is fittingly full to the rafters with iconic costumes worn by Bond stars from Dr No right through to the latest film, the upcoming Skyfall

From here it’s into a space dedicated to Bond’s original creator, the great thriller writer that was Ian Fleming, which impressively boasts several first editions of his novels, with their colourfully captivating covers catching the eye. Next it’s back into the Eon film universe, as on one side you pass mock-ups (using real props) of two of M’s offices and on the other side paraphernalia of the character of Bond himself (including, yes, the aforementioned PPK and passports). Fittingly, the next space is named ‘Q Section’ and features a (pleasingly over-)abundance of gadgets supplied by the incomparable Q and used by our man Bond throughout the series – clever weapons, bug detectors, vehicle models and, yes, even that Amstrad 64-esque ATAC thingee from For Your Eyes Only (1981) litter this room; there’s something familiar literally wherever you look.

Without pausing for breath, you’re quickly on to another delight: the room monickered ‘Casino’. Here you’re immediately faced with mannequins lined around the space wearing (mostly) original suits, ballgowns and costumes originally worn by Bond stars throughout the series. Highlights are obviously the tuxedos worn by several Bonds themselves (each mannequin for which features a face supposedly resembling that of the appropriate actor, the results of which are admittedly rather comical but fit with the overall exhibition’s somewhat self-mocking tone; much like that of the films themselves then, you might say).

Still, worth checking out too during your gander of all these garments are Valentin Zukovsky’s enormous tuxedo from The World Is Not Enough (designed by actor Robbie Coltrane’s own tailor), Sylvia Trench’s striking gown from Dr No (1962), Vesper Lynd’s beautifully elegant purple effort from Casino Royale (2006) and – as something of a teasing taster – new girl Sévérine’s outstandingly vampish dress from this year’s Skyfall. Oh, and this room also offers an unexpected gem (as it were) in the shape of the Fabergé egg made specially for Octopussy (1983).

After a quick sojourn through a space that’s open to the public, but still filled with Bond-related artefacts, it’s now on to a ‘Villains’ room, featuring alongside the liquid-nitrogen-afflicted Boris, Jaws’ molars and Tee Hee’s arm and claw, further costumes and props worn by and wielded by the baddies of Bond’s universe. Notable inclusions are scale models of the Rio de Janeiro cable car and the space shuttle and figurines of Hugo Drax and his minions aboard his space station, all of which were used for the filming of Moonraker, of course. Why’s the Drax figurine so memorable? Because close-up he resembles Japanese TV favourite Monkey rather than that film’s megalomaniac villain. A coincidence maybe, but rather marvellous to my mind.

Model perfection: Eon artefacts such as this miniature of The Spy Who Loved Me’s Lotus Esprit – one of several used in the movie’s filming – ensure Designing 007 swims rather than sinks

The exhibition’s final space ‘Ice Palace’ is separate from the rest of the rooms and accessed via lifts (festooned with quotes from the Bond films), but that’s no matter, and, yes, its centre-piece is a large model which was used for the filming of Die Another Day (2002)’s ice palace, while a general snow-cum-ski theme is maintained by several props and costumes associated with snow-bound action from the flicks, including the so-tasteless-it’s-awesome banana-yellow ski suit worn by Sir Rog in the terrific pre-title sequence from The Spy Who Loved Me.

And so, that’s that? Well no, actually. Because now you can visit a rather sleekly appealing martini bar – which, yes, fittingly only serves martinis – and quaff a very Bondian beverage following your hard morning’s/ afternoon’s/ evening’s work re-familiarising yourself with so many 007 delights. And sort of pretend you’re 007 yourself while you sip your Vesper, of course.

Overall then (and not least because it also boasts the martini bar) this exhibition is a resounding success. Both its comprehensive collection and quality curating ensure that for a massive Bond fan like myself it’s a cornucopia of 007 goodness; an Aladdin’s cave of Eon wonders. And making its (present) home The Barbican is an excellent choice too – not least because the stark modernism of that fine venue’s interiors echo the design of so many Bond films, but also as its exterior actually featured in a Bond film, 2008’s Quantum Of Solace, that is. So, if you’re an inhabitant of these isles, this scribe’s advice to you is definitely to give Designing 007 a visit – before September 5 when, oh-so Bond-like, it disappears on a deserved tour of different destinations around the world.

.

Further reading (and for opening times and ticket prices):

http://www.barbican.org.uk/bond

.

.

“I admire your luck, Mr…?”: luck had nothing to do with it, the casting of rough, tough Scotsman Sean Connery as 007 in the first significant James Bond film Dr No was a stroke of calculated genius – even if it certainly didn’t appear to be a trump move at the time

On October 5 1962, a critical, pivotal event took place, something that would ensure the cultural zeitgeist – if not the entire world itself – would never be the same again. For it was on this day that the cinematic James Bond was arguably born, with the world premiere of the first Eon-produced 007 film adventure Dr No being staged at the salubrious Odeon Cinema in London’s ritzy Leicester Square.

And rolling up at the venue that evening (surely the biggest night of his professional life to date) was the man who was playing the British superspy himself, Sean Connery. If anything was likely to prove a fly – nay, a scary, creepy-crawly tarantula – in the big-screen Bond’s ointment before he’d really got begun then, by rights, it should have been Connery. To many an observer at the time, his casting as the three-dimensional incarnation of author Ian Fleming’s hero had raised more than a Roger Moore-style eyebrow. Why? Because – and, as we’re talking about Sean Connery here, it almost seems impossible to contemplate this – the Big Tam was a nobody. He’d been plucked from relative obscurity to lead a $1million-budgeted Anglo-Hollywood action adventure; it was a big risk with bells on and it could have gone tits up. But, of course, it didn’t.

Indeed, unquestionably the casting of Connery was one of the reasons why Dr No went on to become such a box-office triumph, setting the whole 007 tyre-slashing Aston Martin wheel in motion. But given his lack of standing in the movie business, how on earth did he land the role? And given his relative lack of leading man acting experience, how come was he such an instant, indubitable success? This, my friends (the latest post in this blog’s continuing series celebrating the movie Bond‘s 50th anniversary), is that story.

Connery primarily owed his casting – and, arguably, success – as James Bond to three men: Dr No‘s producers Albert R ‘Cubby’ Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, and its director Terence Young, but certainly not to the character’s original literary creator Ian Fleming. When the latter heard the Scot had landed the role, he apparently dismissed him as an ‘overgrown stuntman’. He would eventually reverse this opinion, but taking a look at Connery’s credentials you can understand where his priggish, even snobbish stance came from.

.

.

Hailing from the hard, working-class Edinburgh neighbourhood of Fountainbridge, Thomas Connery had earned his nickname ‘Big Tam’ by, well, growing bigger and taller than anyone else. Unsurprisingly, aged just 18 he’d begun body-building and by 21 had competed in the Mr Universe competition. Vocation-wise, he’d had odd-jobs as a lorry driver (his dad’s profession), a milkman, a boxer, a lifeguard, a coffin polisher, an artists’ nude model and he’d enjoyed/ endured a stint as a seaman in the Royal Navy. He eventually discovered his true calling when he helped out backstage at Edinburgh’s Kings Theatre and then won a small chorus line role in a touring production of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical South Pacific. It was during this tour that, while playing football against a provincial town team, he famously caught the eye of Manchester United’s legendary manager Matt Busby, who supposedly offered him a £25 a week contract with the club. Connery turned it down; it was an actor’s life for him now.

Bit-parts in British films followed (for which he adopted the stage name Sean, actually his middle name), including the Stanley Baker vehicular vehicle Hell Drivers and Action Of The Tiger (both 1957), the latter of which, like Dr No, was directed by Terence Young. The following year he landed a major role in Paramount Pictures’ melodrama Another Time, Another Place opposite Hollywood actress Lana Turner, with whom he had a brief affair and the result of which was fisticuffs (won by Connery) with Turner’s gun-wielding boyfriend, Johnny Stompanato – who just happened to be a heavy working for LA gangster Mickey Cohen.

Mixing it up, Connery’s next starring role was as far away as anything from demonstrating a hard-man persona; it was in the Disney Irish whimsy-themed musical Darby O’Gill And The Little People (1959), in which he not only sang, but also played opposite leprechauns. And as the ’50s slipped into the ’60s, he took on Classical roles, featuring prominently in British TV productions of Anna Karenina (1960) and Shakespeare’s Henry IV (1960) and Macbeth (1961).

So far so good. Connery was slowly but surely building up a catalogue of work that could have resulted in him becoming a recognisable face on UK TV; a tough guy who’d escaped the rough and ready streets of Scotland’s capital for the respectability of the jobbing actor. What happened next, of course, changed all that. Having signed a contract with film studio Twentieth Century Fox, which he soon discovered had merely left him on the shelf like so many Hollywood hopefuls who’d done the same (his biggest role thanks to this contract was a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it appearance in 1962’s war epic The Longest Day), his agents earned their corn like never before – and surely like never since – when they set him up for a meeting with two gentlemen named Broccoli and Saltzman.

Big Tam and ex-pats: an on-set Connery confers with Bond creator Ian Fleming (l) and goofs around with Fleming’s Jamaican neighbour and one-time possible Dr No, Noël Coward (r)

The Italian-American Broccoli, formerly a New York lawyer, and the Quebec-hailing Canadian Saltzman, who liked to see himself as something of a cinematic showman, had already been in the movie business for years, albeit working separately. In 1961 they came together and formed Eon Productions, a company set up specifically to make film versions of the Bond novels (their Danjaq company – named after both men’s wives, Dana and Jaquie – was set up as a holding company for the films’ intellectual properties).

Broccoli had previously co-founded and run Warwick Films with producer Irving Allen. Warwick was based in London and used many British film professionals as crew-members on its movies (such as future Bond alumni Terence Young, screenwriter Richard Maibaum, cinematographer Ted Moore and stuntman/ stunt arranger Bob Simmons) in order smartly to save money and, thus, well, make more money. Turning out the likes of the Rita Hayworth starrer Fire Down Below (1957), Warwick was finally sunk by the box-office turkey that was The Trials Of Oscar Wilde (1960) – its accurate, but controversial homosexual themes ensuring early ’60s American censorship killed its publicity. Broccoli then was soon looking for a new Britain-based opportunity. He didn’t have to look very far.

Harry Saltzman had moved his family to Britain to further his career as a theatre producer and had quickly entered the film business. In then forming Woodfall Film Productions with dynamic young director Tony Richardson (who would go on to direct 1963’s Best Picture Oscar winner Tom Jones and marry Vanessa Redgrave) and leader of the ‘Angry Young Men’ playwrights John Osbourne, Saltzman had played a spear-heading role in launching the ‘kitchen sink’ genre of late ’50s/ early ’60s UK cinema – he personally produced both the acclaimed Look Back In Anger (1959) and The Entertainer (1960). Yet, always ambitious, he had wanted to make films that would turn a bigger profit and in 1961 he was sure he had found just the vehicle.

Having read Ian Fleming’s 1959 Bond novel Goldfinger, he had become convinced 007 was what he was looking for. Despite notorious legal disputes arising from an aborted screen-treatment for a big-screen Bond adventure knocked up by Fleming, fellow writer Jack Whittingham and eccentric film producer Kevin McClory (which saw the latter two gang up on the former when he turned the treatment into the 1961 novel Thunderball with no formal credit to either of them – read more on that here), Saltzman approached Fleming to buy the film rights of all his novels. The author assuaged and Saltzman got what he wanted (with one or two limitations), albeit for a mere six-month option and at a very pricey $500,000; always the gambler, though, he was confident he could get a first film set up within that half-year window.

.

Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile

- One evening before Dr No‘s premiere, the first broadcast took place of ITV’s classic spy-fi series The Saint (1962-68), starring, of course, one Roger Moore

- On the exact same day as the Dr No premiere, The Beatles’ very first single Love Me Do went on sale in the UK

- Just nine days after the premiere, the Cuban Missile Crisis began, which saw the United States and the Soviet Union come perilously close to tumbling into nuclear war, only for both to blink at the last moment – in a sort of ‘life imitates art’ manner, Dr No’s evil plan aimed to accelerate the tensions between the US and USSR and push them to nuclear war

Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile-Factfile

.

In actual fact, Broccoli too had been interested in pursuing Bond as a big-screen project, but Irving Allen had maintained that the character and his adventures weren’t even good enough for television (Fleming’s first novel, 1953’s Casino Royale, had been adapted into a one-hour TV drama in 1954, which had been pretty forgettable) – Allen had even met with Fleming and snubbed both him and the opportunity to buy the rights for Warwick Films. But now Warwick was no more and, thanks to a meeting with legendary screenwriter Wolf Mankowitz, Broccoli learned Saltzman had bought the rights and approached him. Call it destiny, call it kismet, call it a fait accompli… call it what you will: Saltzman, the relative filmmaking novice with the ‘outside of the box’ thinking, was a natural fit with Broccoli, the hard-nosed and relatively successful industry insider; the former not willing to sell any part of the 007 rights to the latter, they agreed to put Bond on the silver screen together and, yes, chose to adapt the 1958 novel Dr No as their new company, Eon’s first.

And, in one of their canniest moves, Broccoli and Saltzman gathered around them a crew of filmmakers especially familiar to the former from his previous projects, including (as mentioned) Maibaum, Moore, Simmons and – most significantly for this tale – Young. For it was thanks to their masterstroke of hiring Terence Young as helmer of the film that the leading actor they cast as Bond went on not just to play the role, but truly inhabit it.

Speculation, wishful-thinking and, quite frankly, myth-making has been at work since the very beginning on who could have, was in the frame to and ‘should’ have played Bond. Word has it Fleming had always favoured his friend David Niven, who gets a mention in the 1964 novel You Only Live Twice as ‘the only decent man in Hollywood’ and would play one of several Bonds in 1967’s crazy spoof comedy version of Casino Royale, which ironically was co-scripted by Wolf Mankowitz. He was also apparently keen on Cary Grant – supposedly the latter would only commit to one film rather than a potential series, but surely in the end Broccoli and Saltzman would have concluded he was too old by 1962 anyway. Other names that have been bandied about include later Bond Roger Moore,who was committed to TV’s The Saint (1962-68), Patrick McGoohan on the strength of his spy drama series Danger Man (1960-68) and – rather unlikely, yet given the number of times he’s admitted to it in public, it’s probably true – future BBC newscaster Peter ‘Swingometer’ Snow auditioned too.

Apparently, Broccoli and Saltzman even ran a ‘Find James Bond’ contest in an attempt to cast the role (so the story goes, a model named Peter Anthony won this competition, the producers liking a Gregory Peck-esque quality to him), but ultimately this wasn’t how they found their man. As noted, it was through a conventional agent-set-up meeting that they met and auditioned Connery. Yet, by rights, the latter should have blown his chance here before he even got started on the gig.

.

.

An actor of little leading man experience on the screen, Connery ‘put on an act’ in the meeting – displaying an air of nonchalance; even tough-guy devil-may-care. That may have proved to work for him in media interviews for decades to come, but it was a definite gamble in clinching his first major film role. And yet it worked. Broccoli and Saltzman liked what they saw, heard and felt from him in that meeting. But apparently what sealed it was the way he walked; both felt his ‘cat-like’ gait (watch him move as Bond in the early films, it’s like a panther) as they watched him through the window of their Piccadilly office walk away down the street. This was their Bond, they decided.

Now enter Young. Although no doubt pleased to be working with a crew assembled from people familiar to him from his Warwick Films days, he wasn’t with the script. The producers had insisted on adapting Dr No as a detective-style adventure with science-fiction elements (almost playing down the espionage of the literary Bond, although admittedly there’s less of that in Dr No the novel than others), believing this would be the most palatable way to deliver an adaptation to the big-screen audience. Indeed, this may well have been one of the reasons they cast the ‘overgrown stuntman’ Connery – rather than perhaps a lither, David Niven-like, more Fleming-friendly actor – as their 007.

All the same, Young felt the script (having gone through several drafts already and a walk-out by Wolf Mankowitz) required more work still. Thus he charged credited screenwriters Richard Maibaum, Johanna Harwood and Berkely Maher to inject humour into the proceedings. In his eyes, to appeal truly to the audience, Bond needed not only to be burly, handsome and sexy, he also had to be witty, charismatic and charming – as much, if you will, Simon Templar as Richard Hannay.

This too meant Connery needed working on. The actor wasn’t a hack, far from it, but he wasn’t James Bond – certainly not Young’s vision of James Bond. So in the few short weeks before filming began, Young took Connery under his wing and introduced him to the rarefied world of tailoring (dressing him in the suits of Anthony Sinclair, his own tailor), London’s fine dining and how to move and speak like a gentleman (forbidding Connery to talk with his hands – a Young bête noir – and embellishing his cat-like walk, while softening his Scots accent to deliver the script’s witticisms).

Shooting the breeze and suiting you, sir: Broccoli chats with Dr No cast members John Kitzmiller, Sean Connery and Ursula Andress (l); Connery fitted for an Anthony Sinclair suit (r)

In fact, over the years, many have suggested that Connery’s Bond – or even Terence Young’s Bond – was Terence Young. He may be a cold-blooded killer, a man with a razor-sharp mind and an exuder of extreme confidence and unthinking bravery, but the Bond template established in Dr No is also unquestionably a man immaculately turned-out (the best possible Saville Row tailoring, never a hair out of place and minimum body movement), a true bon vivant (an enthusiast of the finest wine and food) and possessing the charm, wit and even superiority complex of an English gentleman.

You may be sceptical of Young’s domineering influence on Connery’s performance (given how much the actor has impressed in a variety of roles throughout his long career), but an insider of the calibre of the sadly departed Canadian actress Lois Maxwell – Miss Moneypenny herself – affirmed this was exactly how the director took the star-to-be in hand. She didn’t outright claim that Connery did a Terence Young impression (given Bond’s latent power, sexiness and at times brutality – that’s all Connery – he didn’t), but she didn’t get far from it.

And by the end of filming, a star-to-be Connery most certainly was. Dr No, with its fairly modest $1million budget, brilliantly inventive, nay unforgettable sets (designed by near genius Ken Adam, but partly made of cardboard) and relative unknown leading man and supporting cast, was genuine box-office boffo. Its worldwide gross of $59.6m (inflation adjusted: $440.8m) ensured it made monstrous profits for its producers and studio backer United Artists. And, of course, thanks to his performance and unquestioned screen magnetism, Connery very quickly became a bona fide moviestar.

It would, as we all know, only get better for him – and Broccoli and Saltzman. His five further Bond films – From Russia With Love (1963), Goldfinger (1964), Thunderball (1965), You Only Live Twice (1967) and Diamonds Are Forever (1971) – rang cinema tills to the colossal combined tune of $563m, making him and them very rich men. Well, actually them supposedly richer than him, which was definitely one of several bones of contention for the star as the series continued through the ’60s and Connery the man became practically indistinguishable from Bond the character in the mass public’s mindset. Eventually then, Broccoli and Saltzman were faced with having to pull off the seemingly impossible: cast someone else as James Bond.

But, as the negative doctor might say, no… no more – all that’s for another blog post, peeps…

.

.