007/50: The Bondathon reviews (2000s)

.

So, here it is, peeps, the final trio of reviews following the completion of my ‘Bondathon’ – a chronologically-ordered Bond film-watching marathon (check out reviews of the 1960s era here: 1 and 2; the 1970s’ here; the 1980s’ here: 1 and 2 and the 1990s’ here).

And it ends, inevitably, with the ’00s, a decade of contrasts thanks to boom-and-bust; globalisation and terrorist paranoia; Bush and Obama; QI and blinkin’ X Factor. And the cinematic Bond went through a right about-turn in the ’00s too, what with The Brozzer’s fantastical final bow Die Another Day giving way to the ‘realism’ of Daniel Craig’s Casino Royale and Quantum Of Solace. But just how do they rate and rank according to yours truly? Well, read on and find out, my dear blog-friendly friends…

.

How it works:

- The ‘Bondathon’ takes in all 24 cinematically released Bond films, from Dr No (1962) right through to Quantum Of Solace (2008) – including the ‘unofficial’ efforts Casino Royale (1967) and Never Say Never Again (1983)

- The reviews consist of 10 categories, the inclusion of which tend to define a Bond film as a Bond film (‘Plot‘, ‘Bond‘, ‘Girls‘, ‘Villains‘, ‘Action‘, ‘Humour‘, ‘Music‘, ‘Locations‘, ‘Gadgets‘ and ‘Style‘), each of which are rated out of 10, thus giving the film in question a rating out of 100 – which ensures all 24 films can be properly ranked

- There’s also an ‘Adjuster‘ for each film’s rating (up to plus or minus five points) to give as fair as possible a score according to its overall quality as a film.

.

.

.

Directed by: Lee Tamahori; Produced by: Michael G Wilson and Barbara Broccoli; Screenplay by: Neal Purvis and Robert Wade – influenced by the Ian Fleming novel Moonraker (1955) and the Kingsley Amis Bond novel Colonel Sun (1968); Starring: Pierce Brosnan, Halle Berry, Toby Stephens, Rosamund Pike, Rick Yune, Judi Dench, John Cleese, Samantha Bond, Colin Salmon, Michael Madsen, Emilio Echevarría, Michael Garevoy, Lawrence Makoare, Will Yun Lee, Kenneth Tsang, Rachel Grant and Madonna; Certificate: 12; Country: UK/ USA; Running time: 133 minutes; Colour; Released: November 20 2002; Worldwide box-office: $431.9m (inflation adjusted: $543.6m ~ 11/24*)

* denotes worldwide box-office ranking out of all 24 Bond films (inflation adjusted), according to 007james.com

.

.

Just as Connery had with Thunderball (1965) and Moore with Moonraker (1979), Pierce Brosnan suffers his ‘fourth movie mis-step’ with final effort Die Another Day. Why? It’s big, brash and overblown bunkum, not least its plot. Bond infiltrates a North Korean arms deal held by young Colonel Tan-Sun Moon, but his cover’s blown by an MI6 mole. With his operation gone tits up, 007’s incarcerated for 14 months until diplomatically swapped for Moon’s henchman Zao, who’d been caught by the West. Put out to pasture by M, our man hunts down Zao in Cuba, where he finds the latter in a DNA-face-changing clinic and meets US NSA agent Jacinta ‘Jinx’ Johnson. Tracing diamonds he took from Zao, before the latter escaped his clutches, to an Icelandic diamond mine run by Argentine tycoon Gustav Graves (who’s appeared out of nowhere during his time away), 007 travels to London to meet Graves. Reinstated by M, he’s ordered to visit a demonstration of ‘Icarus’, a diamond-powered, mega solar-power delivering space satellite, at the Icelandic mine-cum-ice-palace, where he’s shadowed by MI6 agent Miranda Frost (doubling as Graves’ assistant) and again meets Jinx. Bond finally realises Graves is Moon, having had his face DNA-changed to that of a Caucasian, and learns Frost is the latter’s accomplice, thus, the MI6 mole that betrayed him.

Ironically, as Pierce Brosnan’s 007 films took a step backwards with each new offering, he arguably stepped further forward with each new performance. By the time of Day, his Bond‘s at the height of its smooth and cool, ultra confident, yet vulnerable and human Bondness – even if in this one he’s forced to sport that Robinson Crusoe makeover following his Korean incarceration (indeed, his I’m-Bond-so-I-don’t-care walk through the hotel lobby with dreadful hair and dripping wet pyjamas is a highlight). Moreover, he delivers with panache both the inane dialogue (post-coital with a girl: “I’m so bad”/ “Even when you’re good”; the shoehorning in of the film’s title: “So you live to die another day”) and the decent lines he’s given (on a cache of diamonds hiding a bomb: “Don’t blow it all at once”; ordering his drink at an ice bar: “Vodka Martini with plenty of ice – if you can spare it”). Overall then, he’s the heartbeat of the film that, when possible, keeps it grounded and engaging – far from a bad way for him to bow out of Bondage.

.

.

Despite deploying big names as main characters in the past, the Eon series has never suffered from ‘stunt casting’; this time it definitely does. Hiring Hollywood star Halle Berry to appear opposite Brosnan as NSA operative Jinx reeks of opportunism and obviousness. There was nothing subtle about her marketing as a co-star (she shared Brosnan’s ‘Bondian pose’ on the main posters), neither is there much subtlety about her performance – not least the overdone Ursula Andress in Dr No (1962) homage that’s Jinx’s entrance, rising (less Venus-like, more orgasmic) from the sea in a bikini that just keeps Ms Berry’s bosom in place. The latter’s a competent actress, but for all her screen-time and publicity, her character’s an underwritten, clichéd Bond-as-action-girl, saddled like everyone else with hokey dialogue. Much better among the girls, though, (and nearly saving this facet of the film) is the perfectly lovely Rosamund Pike as the far from English Rose-like Miranda Frost. The Pikelet delightfully gets her teeth stuck into this duplicitous British agent, barely tolerating Bond as she sexily beds him and coming undone in her action showdown with Jinx thanks only to her hubris. Don’t doubt it, Pike’s Frost may just be the best thing in Day.

On the one hand, given Gustav Graves is supposed to be a mock-Bond clone, you could say Toby Stephens’ snidely sneering, overtly sartorial and overall Elliot Carver-like pantomimic baddie works; on the other, you could say he’s a crap villain delivered by an otherwise more than decent actor. And afraid I’ll have to go for the latter option, guys – but I’d blame ill-conceived direction from Lee Tamahori (far from his only mis-step on this flick) and the daft script much more than Stephens here. The rest of Day‘s villains are no better. Will Yun Lee’s pre-Graves Moon is a spunky young hothead, but limited only to the pre-titles; Michael Garevoy’s tecnho aide Vlad is a bit of a Boris Grishenko from GoldenEye (1995), but without the humour; and Lawrence Makoare’s heavy Mr Kil seems to exist only for a terrible pun on his moniker (“That’s a name to die for” – ouch!). In appearance alone, the movie’s best badguy is Rick Yune’s Zao, his diamond-encrusted, blue-eyed visage and half-DNA-transformed bald bonce a memorably dynamic look, but lacking any personality, let alone charisma, he’s ultimately a forgettable let-down.

.

.

In many ways, its action is Day at its worst; in others, it’s actually strangely satisfying. There’s something of the watching-a-car-crash about Bond’s bad CGI para-surfing a tidal wave with parts of Graves’ ice-speeder as the latter uses Icarus to destroy the very ice on which it was speeding, just as there is about the huge Antonov plane-set climax getting ever more ridiculous as Bond and Jinx veer the thing towards Icarus’s pathway of pure sunlight destroying everything on its way to the Korean 37th Parallel, while, respectively, Jinx and Frost and Bond and Graves (the latter wearing, yes, a Robocop-esque suit) duke it out like they’re in a Jean-Claude Van Damme ‘bargain bin’ flick from the ’80s. Better (if only by degrees) are the pre-titles’ hovercraft chase towards the South Korean border and the Icelandic ice lake-set duel between Bond’s gadget-laden Aston Martin Vanquish and Zao’s exactly the same gadget-laden green Jaguar XKR. Easily the best sequence, though, is the introductory showdown between Bond and Graves at the London fencing club. Moving from foils via several blades all the way up to broadswords, it’s little more subtle than the aforementioned scenes, but genuinely finds the right blend of self-mockery and blood-pumping spills, while standing alone as a rare example of sword-play in the cinematic Bond.

As much – if not more – than any other Bond flick, Day mostly strives for a very light tone, but too often its humour falls as flat as a wrong-side-up slice of toast. There are a few funny moments, such as the satisfying Q scene in the abandoned Tube station (its 40th anniversary homages executed well, unlike those in the rest of the flick), in which the rolling in of the invisible car prompts Bond to observe of Q: “Maybe you’ve been down here too long”. Yet there’s too many other ‘funny’ moments that make one wince; Bond and Jinx’s first meeting on the Cuban beachfront being a prime example – its dialogue, including Jinx commenting on 007’s claim he’s an ‘ornithologist’ by glancing at his crotch and punning “Boy, now there’s a mouthful”, is like something out of the craptastic ’70s Confessions series. Admittedly, now and again subtle humour glints through too, such as Brosnan and Dench’s (by now) well honed witty byplay and his interactions with Emilio Echevarría’s splendid Cuban agent Raoul, but it’s all too fleeting.

.

.

Let’s face it, the inclusion of Madonna’s techno-inspired warble-fest as this flick’s title song is pretty unforgivable – it sounds like the result of her and a producer buggering about in the recording studio after a boozy lunch. (Indeed, the inclusion of the chanteuse/ sort-of movie actress in a cameo at the start of the fencing club scene’s unforgivable too, but really that’s got nothing to do with Day‘s music). As if uninspired by what’s going on on-screen – as the great John Barry seemed to be when composing for that other 007 mis-step The Man With The Golden Gun (1974) – David Arnold turns in a score here that’s down on his usual standard. Taking up the scoring trend he started for himself in directly preceding entry The World Is Not Enough (1999), that is (like Madonna’s dire tune) sound-tracking visuals with techno-esque beats, he runs with it yet further (Gunbarrel/ Surf’s Up, Hovercraft Chase, Whiteout, Ice Palace Car Chase, Iced Inc, Antonov – take your pick). Better, though, is the recurrence of the love theme from the final scene of TWINE (Christmas In Turkey) in this one’s final scene: Going Down Together. But by far the best theme – and easily one of the best of Arnold’s entire Bond canon, mind you – is Cuba/ Cuban Car (click above image to hear it), which, yes, accompanies our man’s arrival in Havana. Full of Latin rhythms and perky brass, it weaves the Bond Theme wonderfully into a fine ethnic scene-setting cue.

Like with too many of the Brosnan Bond films, you come away from this one thinking he’s visited more exotic locations than he actually has. Thanks to the (admittedly sensible) finding of cheaper and/ or more realisable alternatives for others, the only genuinely impressive locale in Day is Iceland with its unearthly white-blue jagged clumps of ice. Or, to be specific, Vatnajökull, on whose ice lake the explosive car chase takes place. As said, you wouldn’t know it, but the Havana and ‘Los Organos’ DNA clinic scenes were filmed in Cádiz in Spain’s Andalucia region, while the bio-domes of Cornwall’s Eden Project stand in for Graves’ Icelandic diamond mine and UK locales as exotic as Aldershot were substituted for North Korea (especially in the opening hovercraft chase). At least London’s Westminster Bridge and Buckingham Palace are the real thing, although the drowning out of the shot of the latter with The Clash’s London Calling has always been an overly modernist bone of contention for many Bond fans.

.

.

As an OTT Eon entry, it probably comes as no surprise that Day does all right on the gadgets front – one or two of them are actually quite cool, dinky, subtle and useful. Take the sonic agitator ring that, when twisted on the wearer’s finger, causes a glass surface next to which it’s placed to shatter owing to the high-pitched squeal it emits (Bond deploys it to escape capture by his foes in Graves’ ice palace bio-dome HQ thingee). Take too maybe the movie’s neatest and best ’40th anniversary homage’, a slightly sleeker and more modern-looking mini breather (updated from the one in Thunderball), which he uses for some underwater activity in Iceland. Less impressive is yet another laser cutter boasted by 007’s latest Omega Seamaster watch, a surfboard with a hidden panel that contains explosive, a knife and a mini-computer and, worst of all, Graves’ ‘dream machine’, which he uses for a couple of hours each day to keep him sane because he has permanent insomnia following his gene-therapy treatment (WTF? How does that even work?), looking as it does like a Rastafarian’s psychedelic face-mask thanks to its trailing dreadlocks.

Although from the halfway point on, Day descends into fantastical nonsense, very often it looks darn good. Indeed, at times, its style is a saving grace. In his final appearance, The Brozzer looks as dapper as ever – and when not is cool-as-you-like in his Cuban shirt and shades, bombing around in his Ford Fairlane retro roadster, smoking cigars and drinking mojitos; or alternatively escaping from HMS MI6 for a salubrious Hong Kong hotel looking like something the cat dragged in (which, for the funnies, equally works). There’s also, of course – and importantly so – the return of the Aston Martin to Bond, in the shape of the modern but beautiful Vanquish. And yet, eccentrically, what’s good about this flick’s often what’s bad about it too. Not least the Vanquish, which infamously becomes the ‘Vanish’ (finally a daft gadget too far for all 007 fans), while director Tamahori’s colouful, luxurious visuals and good pacing inexplicably give way to a jerky, The Matrix-style slo-mo gimmick, presumably employed to make scenes look ‘cooler’, and over-cooked, crazy action sequences that would fit better in Looney Tunes cartoons (the ice lake chase and the Antonov climax). And all that’s not even to mention Graves’ Robocop suit…

.

Adjuster: 0

Actually rather well executed (mostly) until Halle Berry’s entrance, if not until the jaunt to Iceland, Die Another Day from then on descends into utter overblown codswallop. Clearly the series required a re-think after this entry, but it remains something of a wicked pleasure ‘crap movie’ to lose yourself in after a boozy Friday night down the pub – and that certainly can’t be said of, yes, Licence To Kill (1989).

.

.

Best bit: Bond and Frost’s diversionary snoggage

Best line: “You know, you’re smarter than you look”/ “Better than looking smarter than you are”

.

.

.

.

.

Directed by: Martin Campbell; Produced by: Michael G Wilson and Barbara Broccoli; Screenplay by: Neal Purvis, Robert Wade and Paul Haggis – adapted from the Ian Fleming novel (1953); Starring: Daniel Craig, Eva Green, Mads Mikkelsen, Judi Dench, Giancarlo Giannini, Jeffrey Wright, Caterina Murino, Simon Abkarian, Ivana Miličević, Isaac de Bankolé, Jesper Christensen, Sébastien Foucan, Ludger Pistor, Richard Sammel, Tobias Mendes, Claudio Santamaria, Tsai Ling and Verushka; Certificate: 12; Country: UK/ USA/ Czech Republic; Running time: 144 minutes; Colour/ black and white; Released: November 14 2006; Worldwide box-office: $596.4m (inflation adjusted: $669.8m ~ 6/24*)

.

.

Before, when Eon’s series had gone too far one way, they jerked it back the other way, but in following up Day they do more – they ‘reboot’ the entire Bond brand. Casino Royale‘s plot opens with Bond earning his ’00’ status by killing two targets. From here he goes to Madagascar to hunt down terrorist Mollaka, whom instead of allowing to escape, he kills. Unhappy with the ‘blunt instrument’ she’s promoted, M banishes him, but he gets on with the mission – connecting Mollaka to his client, Bahamian-based fixer Alex Dimitrios, whom he seeks out in Nassau, tails to Miami Airport and prevents the blowing up a huge airliner. M next sends him after Dimitrios’s employer Le Chiffre, banker for a criminal organisation, whom has lost a fortune of clients’ money in selling their stock of the would-be blown up plane’s airline. 007 travels to Montenegro, with UK Treasury liaison Vesper Lynd, to defeat Le Chiffre at poker, ensuring he doesn’t make back the money he’s lost. Allied too by MI6 contact René Mathis and CIA agent Felix Leiter, Bond beats Le Chiffre, only for the latter to kidnap Vesper, but be mysteriously offed by his own people with Bond and Vesper’s lives spared. The two fall in love, only for him to discover Vesper, whom commits suicide, was always going to hand the winnings over to the organisation in ransom for a previous boyfriend it holds hostage. Heart-broken but now the Bond we know (more or less), he goes after the money and the next chain in the organisation, Mr White… Using Fleming’s first, slight and tragic 007 novel as its basis, this plot brilliantly blends with it modern terrorist fear and its Bond ‘becoming’ Bond subtext.

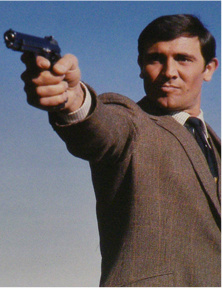

Lambasted for being too short, too ‘ugly’ and, well, blond, Daniel Craig proved many wrong when they finally saw his 007. Crudely, one may say his Bond mixes the smooth, animal-magnetim and physical prowess of Connery with the (supposedly) ruthless, hard realism of Dalton; but there’s much more to it than that. Coming to the role as perhaps its best actor yet, Craig lends him conceivability, a hell of a lot of physicality and brutish charm, yes, but his Bond too goes through one hell of a character arc – from robotic ex-SAS man to fully-fledged 007 via a heart-opening doomed love affair – the like of which, in 20 previous escapades, our hero hadn’t been allowed, not even in the otherwise awesome On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969). By their standards then, Craig’s performance in Royale is indeed magisterial.

.

.

Eva Green’s Vesper Lynd is the best Bond Girl since Diana Rigg’s Tracy in Majesty’s. For this film to work, she has to be too – being that Vesper is the only other of his many girls he genuinely falls in love with (at least in Fleming, but as both flicks are ‘faithful’ Fleming adaptations that statement stands up here). In league with the screenplay’s tip-top outlining of her (a cold, confident over-achiever whose exterior belies a damaged soul), Green nails her character, playing her as cool, witty, caustic and very sexy, but as the film goes on peeling back her skin to show the vulnerability beneath and hinting at why she wears her Algerian love-knot necklace (which Bond, of course, guesses correctly), until the devastating denouement. It’s heart-breaking stuff and all because Vesper’s a complex and convincing character (despite the French Green’s slightly wobbly English accent; a very minor quibble). Royale also boasts the glamour and beauty of Caterina Murino’s Solange, whom as Dimitrios’s wife becomes the flick’s ‘sacrificial lamb’ thanks to Bond’s interference, and a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo from supermodel Alessandra Ambrosio, whom along with Craig’s on-set assistant Veronika Hladikova, walks past 007 outside the Bahamian Ocean Club.

Why Royale‘s villains work so well is because they’re such cruel, ruthless, evil b*stards. They’re grown-up Bond villains in a grown-up Bond film whom, with its serious tone and twisty-turny plot, make you wonder whether they may actually get the better of our rookie hero. Chief – and best – among them is Mads Mikkelsen’s cruely handsome Le Chiffre. More a nightmarish accountant than an Alec Trevelyan, he shows he can mix it, though, by beating Bond’s crown jewels with a rope as well as trying to beat him in the pivotal poker sequence. He also has an awesome deformity – a tear duct that weeps blood. There’s also Isaac de Bankolé’s genuinely scary Ugandan warlord Obanno; Simon Abkarian’s slimy (and curly haired) bugger Dimitrios; Sébastien Foucan’s free-jumping Mollaka; Claudio Santamaria’s Miami-based terrorist Carlos; Richard Sammel’s one-lens-tinted-black-glasses-wearing and panama hat-sporting Gettler (whom appears in Fleming’s novel) and, best of all, Jesper Christensen’s coldly angular-faced and enigmatic Mr White. To say this bunch is memorable is like saying the Munch Bunch are reminiscent of foodstuffs.

.

.

One of the reasons why Royale kicks arse is because, as well as offering gripping drama, it kicks arse – boasting the series’ best action since Majesty’s. There’s the fast-paced chase and punch-up between Bond and Carlos on Miami Dade’s runway; there’s the climactic set-piece in which our man sinks a Venetian villa by shooting away its air-filled supports and shooting up the heavies; there’s the brutal fisticuffs that see Bond come to bloody blows with Obanno and his henchman (so visceral it seems to defy the flick’s ’12’ rating); there’s the would-be car chase following Vesper’s kidnapping, cut short by 007’s Aston Martin DBS swerving to avoid her in the middle of the road and executing a spectacular world-record-breaking barrel roll; and best of all there’s the sequence that opens everything: Bond’s pursuit of Mollaka. Essentially a foot chase up a crane, dizzyingly on a crane, down a crane, on road and in an Embassy (ending with our man shooting up the joint as he attempts to apprehend his quarry), it’s an utterly thrilling, vertigo-inducing sequence that not only properly introduces to the world Craig’s 007, but also Foucan’s jump-on-and-off-outdoor-things ‘sport’ parkour (free-running). youtube would never be the same again.

Royale is not a ‘funny’ Bond film, yet, in keeping with its overall quality, its humour is perfectly fitting and thoroughly satisfying. Mostly dialogue-driven, it’s a galaxy away from the slapstick and blunt punning of Day; far closer to the successful if slight comedy of Dr No and From Russia With Love (1963). The highlight’s the train scene in which Bond and Vesper meet. Analysing each other and trading witty barbs, the two strike up a sparring banter that continues until the poker game escalates, with Bond (after Vesper’s mock-takedown of him) answering how his lamb was with “skewered – one sympathises”. Elsewhere, Le Chiffre’s torture of a naked, strapped-to-a-chair Bond is defused – but effectively so – by humour (“I’ve got a little itch down there, would you mind”/ “To the right! To the right!”/ “Now everyone’s going to know you died scratching my balls”). Also, our man’s mis-treatment of a tourist’s car and tossing away its keys (to divert security peeps at the Ocean Club) when the latter arrogantly mistakes him for a valet are pure Bond, while Ludger Pistor’s Swiss banker lends an amusing camp lightness that’s never out of place.

.

.

Hands down, David Arnold’s Royale score is his best Eon effort. Like John Barry before him and John Williams for the Star Wars series, his music here plays a critical role in making key scenes work, thereby elevating the overall flick. His best contribution – easily his 007 repertoire’s outstanding composition – is Vesper (click above image to hear it). Piano-led and rather stripped back before it opens up orchestrally, it beautifully, melancholically, even achingly soundtracks Bond and Vesper’s doomed romance from its tentative beginnings right up to its tragic Venetian conclusion (City Of Lovers, Death Of Vesper). Also, Arnold very smartly reflects the plot’s efforts to show Bond’s development into the 007 we know by never giving us the full Bond Theme; just notes of it here and there at choice Bondian moments, often mixing them with the title song You Know My Name‘s theme, which thus works nicely as a one-off substitute for Bond’s most recognisable musical cue (Trip Aces, Dinner Jackets, Bond Wins It All). The aforementioned song, performed as it is by Chris Cornell and written by him and Arnold, is indeed an utter stonker. Finally, though, as Bond at last delivers his trademark line at the movie’s end we get The Bond Theme good and proper in the predictably titled but awesomely swaggering The Name’s Bond… James Bond.

Cannily, this Bond film plays it safe by visiting a pair of ‘classic’ series locations. The Bahamas’ New Providence and Paradise Islands are used not just for the sun-kissed beach- and Nassau-set scenes (nicely echoing Thunderball‘s locales), but also for the Madagascar chase sequence. Venice, of course, is the setting for the heart-tugging finale; as a backdrop for (doomed) romance here, it’s just as – if not more – memorable as it was in Russia and Moonraker. By contrast, Royale also offers a pair of modern classic Bond locations. The first is the languid, expansive, almost melancholic beauty of Italy’s Lake Como, where Bond both recuperates (Villa Balbianella) and Mr White resides (Villa Gaeta) and the second several locales in the Czech Repubulic – whose Barrandov and Modrany Studios are primarily used for interiors shooting. These number the capital Prague (for, surprisingly, the Miami Airport scenes among others), Locket (the Montenegro town square) and the exquisite Karlovy Vary (mostly the casino exteriors).

.

.

Like deliberately serious Eon efforts before it, Royale doesn’t really do gadgets – their minor involvement a conscious effort to get Bond back to basics, as he does quite literally in this movie. Like in Majesty’s then, our man has to use his wits (his pursuit of Mollaka) and his brawn to overcome opponents (his unceremonious killing of both Dryden’s pre-titles contact and later Obanno). In spite of that, though, a couple of devices play pivotal roles plot-wise. The first is the bug that’s injected into his wrist for M to keep tabs on her raw rookie, only to be removed when he’s kidnapped by Le Chiffre. And the second is particularly good, as is it’s the mini-defibrililator that can be accessed in a hidden compartment of the Aston Martin DBS’s dashboard and comes into its own in the tense scene when Bond has to try and save his own life after being poisoned by Le Chiffre’s girlfriend Valenka (Ivana Miličević). For sure, if he existed yet in this new timeline and/ or universe, Q would be proud of that particular gadget.

Make no mistake, Royale‘s delivery in the style department is as hard-hitting as Craig’s Bond in the Hotel Splendide’s stairwell. Thanks to the re-pairing of director Martin Campbell and his cinematographer Phil Meheux (who collaborated so well on GoldenEye), the latter film’s glamorous ‘heightened reality’ is gloriously rediscovered, not least in the capture of the Bahamian, Italian and Czech locations, but also of the ‘Casino Royale’ interiors (hats off then to veteran production designer Peter Lamont for his realisation of this perfect set). The movie’s irresistible look is finely tempered, though, by radical filming choices: the black-and-white pre-’00’-Bond pre-titles; the stark close-ups as Bond and Obanno duke it out; the coldly and austerely shot torture of our man; and the out-of-focus, severe filming of a drugged 007 trying desperately to get the poison out of his system are all departures for the Eon series, but highly effective. Perhaps most memorable of all, mind, are the little touches, such as Vesper’s devastating, unforgettable purple and black ballgowns and the fleeting focus on Craig’s incredibly blue eyes (sat in the dark in his accelerating DBS and as his face, bit by bit, is blacked out at the end of Daniel Kleinman’s dynamic, outstanding opening credits). Overall then, Royale‘s style is a veritable straight flush.

.

Adjuster: +1

Ostensibly an origin tale, Casino Royale does oh-so much more than just reset Eon’s series – from start to brilliant end, it revitalises the big-screen Bond in a way really unlike any before. An excellent adaptation of Fleming’s quite un-Bondian original Bond novel, it introduces Daniel Craig’s new 007 perfectly – hard, urgent, ruthlessly efficient and irresistible, just like the film whose beating heart he is throughout.

.

.

Best bit and best line: Bond ‘becomes’ Bond ~ “The name’s Bond, James Bond”

.

.

.

.

.

Directed by: Marc Forster; Produced by: Michael G Wilson and Barbara Broccoli; Screenplay by: Paul Haggis, Neal Purvis and Robert Wade – title taken from the Ian Fleming short story Quantum Of Solace from For Your Eyes Only (1960); Starring: Daniel Craig, Olga Kurylenko, Mathieu Amalric, Judi Dench, Giancarlo Giannini, Jeffrey Wright, Gemma Arterton, Jesper Christensen, Joaquín Cosío, David Harbour, Anatole Taubman, Rory Kinnear, Tim Piggot-Smith, Stana Katic and Simon Kassianides; Certificate: 12; Country: UK/ USA; Running time: 106 minutes; Colour; Released: October 31 2008; Worldwide box-office: $591.7m (inflation adjusted: $622.2m ~ 9/24*)

.

.

It may be the 22nd, but Quantum Of Solace is a Bond film first – the first direct sequel; its plot kicking-off just an hour after Royale ends. Arriving in the Italian city Siena, Bond (with M) questions Mr White, but the interrogation’s cut short by her turncoat bodyguard helping White escape. 007 follows a lead to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, where he meets a woman named Camille, whom he observes with ‘person of interest’ Dominic Greene. Actually a Bolivian spy trying to get to Greene’s associate, Bolivian army general Medrano, Camille attempts to assassinate the latter, only for Bond (misreading the situation) to ‘save’ her. Bond follows Greene to an opera performance in Bregenz, Austria, where the latter consorts with fellow members of Royale‘s crime organisation, now referred to as ‘Quantum’. Disrupting this meeting, he seeks out ally Mathis, whom has contacts in Bolivia, where Greene’s up to no good. There he meets Camille again and finds Greene’s ecological project is a front to launch a coup that’ll see Medrano take power, then force the latter to agree Quantum runs Bolivia’s water supply for inflated prices. Mathis is killed, but the CIA’s Felix Leiter informs Bond where the deal will be struck so he can prevent it, learn from Greene the location of Vesper’s ‘boyfriend’ (who’s responsible for her blackmailing and suicide) and Camille can take down Medrano. With its political backdrop and emotional backbone, Solace‘s story’s intriguing, engaging stuff.

While Royale‘s crowd-pleasingly perfect ending suggested Craig’s Bond ‘became’ Bond there and then, Solace refutes that. On his sophomore mission, 007’s still in his genesis; he’s still to get Vesper out of his system, find his ‘quantum of solace’ – a bit disappointing admittedly, given his ‘becoming Bond’ was done so well in Royale, but maybe for the best as it gives actor-and-a-half Craig something substantial to play with. Sure, there’s his 007’s becoming smoother and more of a playboy (his introduction to Camille; his swagger at the opera; his treatment of Fields), yet he’s also nursing a broken heart (his drunken, middle-of-the-night Martini binge; his final scene with Camille). He’s more monosyllabic, more robotic than our usual Bond; more Royale than Skyfall (2012). Craig portrays him with aplomb, of course, but when, at the film’s end, in reply to M’s assertion it’s good to have him back, he claims “I never left” and drops Vesper’s love-knot necklace in the snow, for better or worse it’s this moment he becomes Bond (cue the gunbarrel).

.

.

Despite her being one of the most beautiful women to have graced a Bond film and displaying decent acting chops, Olga Kurylenko’s character curiously isn’t the most memorable of Bond Girls. Camille Montes, daughter of a Bolivian army big-wig murdered by Medrano (whom then assaulted her family), is smart, gutsy and believable, thanks to her own Bond-like motivation to hunt down the bad guys and, thus, her own narrative. Yet maybe in this very sober Eon effort she’s just too realistic and not glamorous and flamboyant enough to shine as much as she might opposite Craig’s strong 007 performance. To be fair, mind, Vesper casts a long shadow over this film, thus Camille’s never going to compete in his – and maybe our – eyes. By contrast, lending far more feminine lightness is Gemma Arterton’s perky British Consulate girl in Bolivia, Fields (“…just Fields”; whose first name, the end credits reveal, is ‘Strawberry’ – Solace‘s idea of a gag that). A thorn in Bond’s side before becoming an easy lay and ally, she inevitably ends up the movie’s ‘sacrificial lamb’. She’s killed, covered deflectively in oil, in a neat but almost Die Another Day-esque homage to classic Bond lore (Jill Masterson’s death-by-gold-paint in Goldfinger).

Solace‘s villains, despite all being despicable, feel like they pose nothing like the danger Royale‘s did. And as this flick’s its sequel and so its villains belong to the same organisation that film’s did, it’s bit of a problem. It’s most true of chief baddie Mathieu Amalric’s Dominic Greene, an evil, cruel, devious, almost frog-faced terrorist wheeler-dealer – a Kronsteen from Russia for the 21st Century. But then, had they met, wouldn’t Bond have swatted Kronsteen like a fly? And that’s the point: eventually Bond does just that to Greene; in fact, he doesn’t even kill him, merely leaving Quantum to do so as he gives up the intel Bond wanted all along and is left in the desert. There’s also Joaquín Cosío’s Medrano, more an ’80s action flick baddie than Bond villain; Anatole Taubman’s Elvis, an utterly unthreatening henchman; and Simon Kassianides’ Yusef, Vesper’s ‘boyfriend’ whom Quantum pretended to hold for ransom, yet he’s ultimately more a student than worthy foe for 007. The best of the lot’s easily Jesper Christensen’s Mr White. As enigmatic as he was in Royale, he was originally to be polished off by Bond, but this scene was cut, presumably in case Eon want him and Quantum to return at a later date. Let’s hope one day they do…

.

.

A bone of contention with many Bond fans is Solace‘s action. The conventional wisdom is that, under the supervision of the Bourne film series’ second unit director Dan Bradley, if Solace‘s action sequences don’t entirely solidify the claim Craig’s Bond era has been heavily influenced by Bourne, then this flick’s action detrimentally is. A fair summation? Well, yes and no. While the pre-titles car chase offers dynamic, visceral thrills, its filming and editing’s deliberately disorientating effect irritates as much as it entertains, just as does Bond’s first hand-to-hand skirmish when he’s forced to kill a lowly Quantum operative in Haiti (it’s far from clear how the latter actually dies), while the CGI-ification of Bond and Camille’s single-parachute skydive following the aeroplane dogfight above the Bolivian desert looks rather daft. Yet the action climax in the middle of said desert at the Perla De Las Dunas hotel is satisfying; hard, violent, fiery and fraught, it comprises a real sense of danger and potential death (nay, maybe too dark realism?) for our heroes that few other Bond climaxes can claim to. Even better, though, is the best action sequence, 007’s pursuit of the Quantum-turned MI6 agent Mitchell through Siena’s colourful Palio horse-race, over its rooftops and inside its towers, churches and claustrophobic tunnels. ‘Grittily’ cut like the car chase it may be, but culminates in a riveting few seconds on a rickety scaffolding that’s nail-biting indeed.

Sober and often sombre (owing to its much better quality, it’s darker even than ’89’s Licence To Kill), Solace doesn’t do humour like other Eon efforts, but there are amusing moments. Most obviously the section featuring Fields, as 007 has fun at her inexperience of (ahem) field work by claiming they’re teachers on a sabbatical who’ve won the Lottery as cover for booking into the best hotel in town and seduces her merely by asking her help looking for the hotel room’s stationery. Yep, that line never fails (if you’re Bond). During this section too comes the moment Mathis has to ask their taxi driver, rabbiting on about how he took up his profession, to shut up while he’s on the phone trying to tie up local contacts. Owing to script issues (a writers’ strike forced helmer Forster and star Craig to improvise some dialogue), Solace struggles to deliver decent one-liners, yet Bond opening his near-written-off car’s boot at the car chase’s end to reveal where he’s stashed the accosted Mr White with “It’s time to get out” is quality stuff.

.

.

Just as it had a decade before with Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), Eon’s plumping for a profit-chasing title track in favour of a better song whose theme features prominently detrimentally affects this flick’s music. Jack White and Alicia Keys’ Another Way To Die is a pants attempt at a rocking Bond tune, while composer David Arnold’s fittingly melancholic No Good About Goodbye not only sits well with the score owing to its theme cropping up now and again, but its tone and words also fit the flick perfectly (it appears on Shirley Bassey’s excellent Arnold-produced 2008 album The Performance). In the credit column, mind, is the use of Latin jangly guitars and pipes; lending a pseudo-Spaghetti Western feel in tune with the Central/ South American settings (Have You Ever Killed Someone?/ Perla De Las Dunas/ The Dead Don’t Care About Vengeance), while the reappearance of Vesper’s theme from Royale is welcome and most effective (What’s Keeping You Awake?/ Forgive Yourself/ Camille’s Story/ I Never Left). But the score’s at its best during the the film’s best bit, the Tosca section, when the airy, smooth, memorable and scene-building Night At The Opera takes centre-stage (click on above image to hear it).

Locations-wise, you certainly get bang for your buck from Solace – Bond jet-sets all over the shop. Most obvious and (for this film series) unique are the locales of the Americas, although such tricky filming spots are Haiti and Bolivia that Panama, Mexico and Chile double for them. All the same, they’re impressive stand-ins. Panama’s cities Colón and, er, Panama City do nicely for Port-au-Prince and La Paz (Bolivia) respectively, while the aerial sequence is filmed in the Baja California region of Mexico and the blistering, desolate Atacama Desert in Chile is used for Bolivia’s ‘Perla De Las Dunas’-set climax. Europe, of course, is represented by the seasonally-open floating opera stage at Austria’s Bregenz for the Tosca sequence and Italy’s Tuscany area of Talamone is where Mathis’s Lake Garda-set retirement home can be found, while London’s arts venue The Barbican doubles for the outside of MI6’s HQ. Best of all, though, is the oh-so Italian, picturesque cool of Siena with its Palio horse-race – a Bond film location-and-a-half that one.

.

.

If Royale stripped back the Bond film gadgets quotient, then Solace deepens this trend. Our man’s only proper device is a mobile phone (a Sony Ericsson C902 for those who care), which he deploys as, er, a mobile phone. Granted, it’s connected to MI6’s data files so he can receive intel on Greene immediately he needs it, but now just four years on he could probably do the same through an app. Admittedly, it can also display the faces of photographed individuals when the shooter has merely managed to capture them from the side, which is demonstrated as 007 picks off Quantum members at their Tosca meeting. But then you can probably get an app for that too now. The only other gadgets this film are the cool earpieces the Quantum peeps (and Bond) wear along with their natty ‘Q’ lapel pins at the opera and the rather pointless, out of place touchscreen data desk thing at MI6 HQ. It’s stylish and impressive, but surely more fitting for Star Trek or Star Wars. Or Die Another Day.

At one point Camille comments ‘there’s something horribly efficient’ about Bond – that could be said of Solace‘s style. Not only does helmer Forster employ starkly clean yet cool shots (Bond in a black shirt against a Kubrick-esque, totally white corridor; M and Rory Kinnear’s Tanner exiting an ultra-high tech MI6 set this film inside the almost cruelly modernist Barbican), he also sometimes cuts dramatic scenes to within an inch of their lives, ensuring dialogue from one shot overlaps into the next few ones (Bond’s suspension by M in the hotel room; his and Camille’s journey from the desert back to La Paz on foot and then in a bus). Mind, all this is done with aplomb and sophistication. And ‘sophisticated’ really is the word when it comes to Solace‘s look. This is a Bond movie that contains some artily satisfying visual flourishes; not the ‘New Wavey’ touches of Majesty‘s, but beautiful brief imagery such as a slo-mo flourishing flag as MK12’s (admittedly underwhelming) main titles segue into Siena’s Palio, a lizard relaxing on a desert rock as we move into the climax and a second-long focus on ornamental coloured balls in a bowl in the Perla De Las Dunas. It may all sound facetious, but makes quite the impression, as does the climax’s desert setting, an unendingly oppressive expanse that mirrors our hero’s emotional turmoil. Clever.

.

Adjuster: 0

Short and sweet (or rather, sour), the mere hour-and-three-quarters-long Quantum Of Solace is the Bond film gone art-house. Sort of. An intriguing, often surprising, almost experimental Eon entry, its near unremittingly bleak tone may put off some, just as its blink-and-you’ll-miss-it edited action may put off others, but it remains a solid, desert-set dessert of a sequel to the main course that’s Casino Royale.

.

.

Best bit: The Tosca opera sequence

Best line: “Can I offer an opinion? I think you people really should find a better place to meet”

.

.

.

Rankings

(All scores out of 100/ new entries in blue/ * denotes a non-Eon Bond film)

1. Casino Royale (2006) ~ 90

= On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) ~ 90

3. From Russia With Love (1963) ~ 88

4. The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) ~ 87

5. GoldenEye (1995) ~ 85

= Goldfinger (1964) ~ 85

7. You Only Live Twice (1967) ~ 84

8. Live And Let Die (1973) ~ 82

9. A View To A Kill (1985) ~ 75

10. Dr No (1962) ~ 74

11. Moonraker (1979) ~ 73

12. Quantum Of Solace (2008) ~ 72

13. Thunderball (1965) ~ 70

14. For Your Eyes Only (1981) ~ 69

15. Never Say Never Again (1983)* ~ 68

= Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) ~ 68

= The World Is Not Enough (1999) ~ 68

18. The Living Daylights (1987) ~ 67

19. Diamonds Are Forever (1971) ~ 66

20. Octopussy (1983) ~ 64

21. The Man With The Golden Gun (1974) ~ 62

22. Die Another Day (2002) ~ 61

23. Licence To Kill (1989) ~ 50

24. Casino Royale (1967)* ~ 48

.

.

The James Bond reviews will return…

.

.

.

Playlist: Listen, my friends! ~ November/ December 2012

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or have never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and enjoy…

.

CLICK on the song titles to hear them

.

Peter Sellers ~ A Hard Day’s Night

Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazlewood ~ Some Velvet Morning1

Mina ~ Quelli Che Hanno Un Cuor2

The Gun ~ Race With The Devil

Sarah Vaughan ~ Fly Me To The Moon

The Commodores ~ Machine Gun

Gloria Gaynor ~ (Reach Out) I’ll Be There

Eddie & The Hot Rods ~ Do Anything You Wanna Do

Graham De Wilde ~ Newsweek (Theme from Whicker’s World – 1980 onwards)

Cliff Richard ~ Wired For Sound3

The Lotus Eaters ~ The First Picture Of You

Jesus And The Mary Chain ~ Just Like Honey4

Chesney Hawkes ~ The One And Only5

.

1 An on-location performance filmed for the 1967 NBC TV special Movin’ With Nancy

2 Legendary Italian chanteuse Mina’s cover of the Burt Bacharach/ Hal David standard Anyone Who Had A Heart

3 This video of the pop ‘classic’ features the unforgettable vision of Cliff roller-skating around the concrete centre of Milton Keynes while listening to a walkman – it truly has to be seen (and heard) to be believed

4 As featured in the closing scene of the film Lost In Translation (2003)

5 Arguably one of the all-time classic one-hit wonders (it was #1 in the UK for five weeks), this Nik Kershaw-penned tune appeared both in the Chesney Hawkes-starring film drama Buddy’s Song and over the ending credits of the Michael J Fox comedy Doc Hollywood (both 1991)

.

007/50: The Bondathon reviews (1990s)

.

So, after reaching the Bond fan’s promised land that’s attending the Royal Premiere of Skyfall last week – oh yes! (my thoughts on that flick later) – it’s back to the grindstone of review-writing thanks to my ‘Bondathon’, a James Bond film-watching marathon (the 1960s era’s here: 1 and 2; the 1970s’ here and the 1980s’ here: 1 and 2) this week.

But surely the 1990s Bond film era’s far from a grindstone, boasting as it does the tank-chasing of GoldenEye, the Rupert Murdoch-bashing of Tomorrow Never Dies and the Thames-speedboating of The World Is Not Enough. Or is it? Do – as Elliot Carver’s more ethical peers (certainly in these post-phone hacking days of ours) may ask – the facts fit that story? Well, read on and find out, my blog-friendly friends…

.

How it works:

- The ‘Bondathon’ takes in all 24 cinematically released Bond films, from Dr No (1962) right through to Quantum Of Solace (2008) – including the ‘unofficial’ efforts Casino Royale(1967) and Never Say Never Again (1983)

- The reviews consist of 10 categories, the inclusion of which tend to define a Bond film as a Bond film (‘Plot‘, ‘Bond‘, ‘Girls‘, ‘Villains‘, ‘Action‘, ‘Humour‘, ‘Music‘, ‘Locations‘, ‘Gadgets‘ and ‘Style‘), each of which are rated out of 10, thus giving the film in question a rating out of 100 – which ensures all 24 films can be properly ranked

- There’s also an ‘Adjuster‘ for each film’s rating (up to plus or minus five points) to give as fair as possible a score according to its overall quality as a film.

.

.

.

Directed by: Martin Campbell; Produced by: Michael G Wilson and Barbara Broccoli; Screenplay by: Jeffrey Caine, Bruce Fierstein and Michael France – title Fleming’s Jamaican home where he wrote Bond; Starring: Pierce Brosnan, Sean Bean, Izabella Scorupco, Famke Janssen, Joe Don Baker, Robbie Coltrane, Judi Dench, Gottfried John, Alan Cumming, Tchéky Karyo, Desmond Llewelyn, Samantha Bond, Michael Kitchen, Serena Gordon and Minnie Driver; Certificate: 12; Country: UK/ USA; Running time: 130 minutes; Colour; Released: November 13 1995; Worldwide box-office: $356.4m (inflation adjusted: $529.5m ~ 12/24*)

* denotes worldwide box-office ranking out of all 24 Bond films (inflation adjusted), according to 007james.com

.

.

Finally, after six years away, the cinematic Bond is back in GoldenEye, whose plot aims to place him slap-bang in the ’90s, but with a retro glance back at his past glories. A pre-titles teaser sees 007 and MI6 colleague 006 (aka Alec Trevelyan) in deepest Soviet Russia on a mission to infiltrate and destroy a chemical weapons facility. The job soon goes awry, though, when Bond’s buddy is captured and seemingly executed. Escaping, 007 completes his mission – but without 006. Nine years later, an attack is made on the former USSR’s Severnaya space programme centre by the electromagnetic pulse-toting satellite weapon it controls (‘GoldenEye’). Presuming the attack’s ensured the ability to control the weapon’s been half-inched, a new female M puts Bond on the case. Arriving in St. Petersburg, he has CIA contact Jack Wade put him on to ex-KGB agent Valentin Zukovsky, whom has many hands in many Russian underworld pies. Reluctantly, Zukovsky leads 007 to ‘Janus’ – a big-wig in post-Soviet Ruskkie crime – whom our man finds is a ‘resurrected’ Trevelyan. Escaping from the latter with useful Severnaya ‘pooter expert Natalya Simonova, the pair trace Trevelyan to Cuba, where they discover he’s stolen the ‘GoldenEye’ and with it plans to strike the UK, destroying its economy in revenge for its treatment of his Cossack parents. Post-Soviet- and IT-centric, GoldenEye‘s narrative is wilfully modern, but also unashamedly fantastical.

With its 1986-set kick-off, is this flick pretending Brosnan became Bond that year as he (and Broccoli) had intended and the Dalton years don’t exist? Perhaps not, but no question, in his first foray as 007, The Brozzer makes up for lost time. Yet not in a swaggering manner. His Bond is smooth, urbane and ’90s male model-handsome for sure, but more quietly confident, witty and efficient than cocksure, innuendo spouting and brazen. ‘James Bond’ and ‘his new film’ are the stars here not Brosnan. There’s nothing at all wrong with him, but it’d be over his next three films he’d grow into the role. Note: it’s also with this 007 portrayal that properly for the first time (maybe or maybe not since 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service), the hero’s introspection became a Bond movie trope – his and Natalya’s “How can you be so cold”/ “It’s what keeps me alive”/ “No, it’s what keeps you alone” exchange was quite the revelation.

.

.

The first Bond film of the pro- or even post-feminist era, GoldenEye was publicised as not featuring ‘Bond Girls‘, but ‘Bond Women’ – and it actually lives up to that hype. Both female leads are excellent. Izabella Scorupco’s Natalya Simonova (two names you’d struggle to pronounce with a mouthful of Q’s baguette lunch) may just be the best ever ‘real world’ female foil to Bond. While she realistically screams at a near death experience in the exploding Severnaya base and is scared amid a machine gun battle, she’s also competent, sure of herself, a fast-learner when it comes to espionage techniques and, yes, very sexy. And I mean very sexy. Indeed, she’s the sort of Bond Girl whose presence would certainly improve lesser Eon efforts. Conversely, Famke Janssen’s marvellously monikered Xenia Onatopp is a gloriously fantastic creation, getting off on killing victims by snapping their spines with her thighs during coitus, finding firing guns similarly orgasmic and generally flouting her Georgian background by dressing vampishly, smoking cigars and speeding around in Ferraris. She’s the series’ best villainess since Thunderball‘s (1965) Fiona Volpe. GoldenEye‘s also notable for featuring Brit film star Minnie Driver’s near big screen debut as Zukovsky’s chanteuse squeeze Irina, whom humorously murders a version of Stand By Your Man.

To a nasty-piece-of-work, GoldenEye‘s villains are all intriguing, unusual, satisfying foes. First up is Alec ‘Janus’ Trevelyan. As he’s played by fit and handsome thirty-something Sean Bean, he’s not just a genuine physical match for Brosnan’s Bond, but also a dark alternative to our hero (an almost clichéd fictional villain type, sure, but pulled off well here). Not only does the fact both were one-time mates add unique spice to their tête-à-têtes, but there’s also a sense Trevelyan’s insight into Bond’s psychosis may give him a genuine edge. It’s a shame then that Bean’s accent can’t decide between being an RSC brogue or his native Sheffield tones, but what can you do? Elsewhere, Gottfried John gives a hard, almost earthy performance as former Soviet turncoat General Ourumov (a hundred times more conceivable than Steven Berkoff’s pantomimic Orlov in 1983’s Octopussy), while at the other end of the spectrum, Alan Cumming’s weaselly nerdish rogue Boris Grishenko may be an acquired taste, but I’ve a huge soft spot for him.

.

.

When it comes to GoldenEye‘s action the first thing that springs to mind is the tank chase. It’s the mid-movie money-shot – or sequence – that must have sounded irresistibly bombastic on paper (‘Bond destroys half of St. Petersburg – in a tank!’), but it’s smartly planned and executed, as 007’s borrowed battering-ram chases Ourumov’s car – the latter having kidnapped Natalya – through the sites of Russia’s most picturesque city. Yet, for me it never quite delights as much as it might – not to say it’s pedestrian, but it doesn’t hit the heights of, say, Live And Let Die‘s (1973) speedboat chase. Or those of this flick’s outstanding pre-title sequence, which opens with a very ’90s-friendly, damned dangerous looking bungee jump down a huge dam and closes with a seemingly law-of-physics-defying free-fall as Bond successfully catches up with a pilotless plane by diving after it over the edge of a cliff. Mention too should go to the destruction of the Severnaya centre, which with Natalya caught right in the middle plays like a disaster movie set-piece; explosions here, falling masonry there, life threatening danger everywhere. And top marks go to the flick’s finale. The series’ best climax since The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), it sees an underground lair go boom, while 007 faces off with 006 dizzyingly high above it on a satellite dish – with a brutal punch-up between them that echoes Bond versus Grant in From Russia With Love (1963).

In keeping with Brosnan’s laconic new 007, GoldenEye‘s humour (the tank chase apart) is less-is-more. The movie’s comedy mostly comes in the shape of sardonic wit (Xenia tries to kill Bond via her favourite method, cue his killer line as he points his PPK at her: “No more foreplay – take me to Janus”; M on MI6’s impressive state-of-the-art satellite-delivered monitoring of Severnaya’s destruction: “Unlike the CIA we prefer not to get our news from CNN”). It’s the early Eon humour of Russia and Goldfinger (1964) and, as such, visual gags include the likes of Bond’s double-take to Natalya’s sarcastic “Either way, I’m fine thank you” after they’ve just scarpered from Trevelyan’s exploding lair and, of course, the very first, nicely understated, but self-mocking tie-straighten from The Brozzer mid-way through an action sequence (the tank chase). Admittedly, the comedy provided by Robbie Coltrane’s knowingly vulgar Zukovsky and Cumming’s Boris (“I’m invincible!”) is pretty broad, but as it’s good stuff, it’s more than welcome for me.

.

.

A bone of contention for many Bond fans is GoldenEye‘s music. Few have many gripes about U2 pair Bono and The Edge’s marvellously flamboyant title song performed with Bassey-esque bombast by Tina Turner. Instead, their grief is aimed at composer Éric Serra’s idiosyncratic score. Favouring guitar-ish electronica and, to the layman’s ear, what seems like metallic sound effects over the strong showtune and/ or orchestral melody and brass highlights of the John Barry ‘Bond sound’, the man behind the music of Luc Besson’s The Big Blue (1988), Nikita (1990) and Léon: The Professional (1994) delivers a radical departure for Bond scoring here. As far as mainstream cinema goes, Serra’s contribution to Bondom is definitely avant garde, but for me, must admit, it works. Its reliance in some sequences on echoing Russian-esque bells offers the onscreen action effective eeriness, while its very electronic percussive-heavy rendition of The James Bond Theme (with synthy delivery of its high notes) is unique and pretty memorable – and suits the murky, concrete grey but unstable, unsure St. Peterburg underworld of the flick’s first half (listen to a sample by clicking on the above image). Mention too should go to Brit movie and TV ad composer John Altman, whom provided music for the tank chase owing to the producers deciding Serra’s scoring for that sequence was just that bit too radical. Ah well, may’ve been for the best.

Fittingly for quite the retro 007 movie, GoldenEye boasts a classic complementary collision of two major locations. The use of St. Petersburg in the flick’s second third could have been a ‘stunt setting’, being the first time the Eon team went to Russia to film, but it works admirably. The beautiful architecture of its wide Contintental boulevards and the crumbing Stalinist-era statues of its abandoned squares evoke a somewhat glossy, yet down-to-earth espionage-y air. By fine contrast are the bright and vertiginous beaches, jungles and vistas of Puerto Rico (standing in for Cuba) of the final third, as 007 and Natalya stretch their legs, throw on summer- and swimwear and cruise around in sportscars and planes in sunny Central America. Furthering GoldenEye‘s glamour credentials are Monaco (and its famed casino) in the post-titles scenes, while several locales in and around London double for St. Petersburg counterparts, as well as Cambridgeshire’s Nene Valley Railway (last seen in Octopussy) for that city’s train scene.

.

.

GoldenEye‘s gadgets may not be the sexiest, but they’re very worthwhile. Chief among them’s the Parker pen that, when clicked three times, becomes a bomb. It features when Boris, whom by absent-mindedly clicking it sets off the fuse, leads Bond to knock it out of his hand and begin the explosive demise of Trevelyan’s base. Bond also wears an Omega Seamaster wristwatch (now an iconic 007 accoutrement, but making its first appearance here), which boasts a laser that cuts through thick metal and a button that detonates magnetic attachable mines. Other highlights are a pair of piton guns – the first in the pre-title sequence ensures Bond safely reaches the Arkangel dam’s bottom following his bungee leap (and also offers a laser option), the second ensures he escapes the archives room in Ruskkie army HQ by firing a rappelling cord hidden in his belt, on which he swings over an impasse and out through the room’s window.

Coming as its release did in autumn ’95 at the height of a resurgent British popular culture brimming with swaggering self-confidence (Britpop, groundbreaking cinema and TV and controversial art), all of which nodded to Blighty’s ’60s and ’70s cultural heritage, GoldenEye offers not just a slick, modern version of Bondian style, but also a look and feel that owes much to Eon’s Connery era. The script features a high-tech macguffin, the Internet, email, a very feminist leading lady and Boris’s geek chic – this is unquestionably a movie of the ’90s. Yet Brosnan’s suave, perfectly moving, one-liner-delivering 007 in his Aston Martin DB5 is something of an echo of both Connery and Moore’s versions, while the glamorous but unfussy ‘heightened reality’ of the St. Petersburg sequences and a luxuriant, almost luscious palette in the Monaco and Cuba sequences thanks to cinematographer Phil Meheux harks back to the smooth richness of Goldfinger, Thunderball and You Only Live Twice (1967). Additionally, director Martin Campbell’s dynamic shots (for instance, the first showing of Brosnan’s face is merely a close-up of his eyes à la Lazenby’s introduction in OHMSS), is reminiscent of the playful, arty, almost avant garde ‘New Wavey’ cinema of the Swinging Sixties. Style-wise, GoldenEye is definitely the cinematic Bond at its best.

.

Adjuster: 0

Granted, GoldenEye is not perfect (its pace slackens in its middle third), but like The Spy Who Loved Me nearly 20 years before, it’s one hell of a greatest hits package. Marrying the style, wit and confidence of the ’60s 007 with the trademarks of Eon’s fantastical efforts (a subterranean villain’s lair and Bond Girls with innuendos for names) and the ‘real world’ aspirations of the ’80s offerings (the hard espionage of St. Petersburg and Severnaya), this is an ambitiously conceived, smartly realised renaissance Bond flick.

.

.

Best bit: The entire pre-title sequence – the best in the series

Best line: “For England, James?”/ “No, for me”

.

.

.

.

.

Directed by: Roger Spottiswoode; Produced by: Michael G Wilson and Barbara Broccoli; Screenplay by: Bruce Fierstein; Starring: Pierce Brosnan, Jonathan Pryce, Michelle Yeoh, Teri Hatcher, Joe Don Baker, Götz Otto, Judi Dench, Desmond Llewelyn, Samantha Bond, Colin Salmon, Vincent Schiavelli, Ricky Jay, Geoffrey Palmer, Julian Fellowes and Cecilie Thomsen; Certificate: 12; Country: UK/ USA; Running time: 119 minutes; Colour; Released: December 12 1997; Worldwide box-office: $339.5m (inflation adjusted: $478.9m ~ 16/24*)

.

.

The second movie of a long-serving Bond actor’s tenure is about consolidation and Tomorrow Never Dies is no exception. Its plot is a driver here – going for a ‘classic’ Bond film narrative. Our man sets out to discover who’s behind the sinking of a Royal Navy vessel, made to look like the work of the Chinese. The clues the superpower’s not to blame lie in the facts the Brit ship thought it was in neutral territory when actually in Chinese waters, while at a recent arms bazaar Bond broke up a device that sends satellite GPS systems off course was sold and media mogul Elliot Carver’s network somehow gained exclusive video footage of the ship’s sinking. 007 goes to Hamburg to monitor Carver, where he reconnects with old flame Paris (now Carver’s wife) and discovers the GPS-altering device hidden in the tycoon’s HQ. Escaping the latter’s goons, he makes for the sunken ship off the Vietnam coast and finds one of its missiles missing. There, he and Chinese operative Colonel Wai Lin are caught and, again escaping Carver’s clutches, conclude he aims to provoke war between the UK and China (pushing things further by launching the British missile into Beijing), thus creating instability in the latter power so a rogue general can gain control and grant him broadcast rights there for the next 100 years. With its Rupert Murdoch-echoing villain yet rather formulaic Bond plot, Tomorrow Never Dies‘ narrative is both ’90s modern and 007 traditional.

Following his understated 007 debut in GoldenEye, Pierce Brosnan gets the chance to flex more Bond muscles in Tomorrow. Our hero this time possesses more of a swagger and more obvious confidence, dresses with more ostentatious style and delivers more quips and cocky mannerisms. It’s as if he’s more centre-stage; somehow a bigger presence – and ultimately he’s more memorable than he was in the preceding film. The Brozzer’s Bond is developing (and fast) as a sort of cross between Connery and Moore, which is frankly perfect for the times. He does distinct himself excellently, though, in the Hamburg hotel scene, in which (very rarely for 007) he lets his guard down by loosening his bow-tie, drinking too much vodka and coming clean with Paris on why he finished with her years before. It’s arguably the most dramatically satisfying and – in its way – most genuinely Bondian moment of Brosnan’s entire tenure.

.

.

This flick’s girls promise much, but are ultimately underwhelming. Leading lady duties fall to Michelle Yeoh as Chinese 007 counterpart Wai Lin. With her martial arts movie credentials, plus not insubstantial acting abilities (2001’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon‘s certainly testament to that), Yeoh makes for an intriguing and unique Bond Girl prospect. Yet her character never really catches fire. She’s self-assured, very capable and more than comfortable in the action moments (mind, her Saigon base-bound minute or so of martial arts action feels more like the filmmakers indulging her than it does seamless fisticuffs), but despite being a one-time Miss Malaysia she’s not the most beautiful 007 squeeze and the script doesn’t invest enough in her character to make her an always engaging, eye-catching watch. Tomorrow‘s secondary girl is Teri Hatcher’s Paris Carver. More a desperate housewife than a Lois Lane, Hatcher lends her charisma and empathy along with a very American beauty, but Paris is pretty obviously ‘sacrificial lamb’ material – and thus receives little screen time. Even less featured (in a manner of speaking) is Cecilie Thomsen’s clothes-less Professor Inga Bergstrom, the Danish dolly – or boffin – bird with whom Bond shares an Oxford college bed and gives rise to the flick’s best line (see bottom of the review).

A media baron as chief of villains is a radical, dynamic departure for a Bond film – and, due to both the could-be-better screenplay (script rewrites went on during filming) and could-be-better performance from Jonathan Pryce, it’s one that rather disappoints. Unfortunately, Pryce takes too many opportunities to chew the scenery as Elliot Carver (grabbing the hair of a minion fallen asleep at his post as he berates him; performing chopsocky karate as he mocks Wai Lin and referring to the latter and Bond as ‘b*stards’ during the climax). Mind you, Carver’s über-branded media empire is well realised, as is his madness (“the distance between insanity and genius is measured only by success”). There’s also Götz Otto’s main henchman Stamper (a sort muscular Necros from 1987’s The Living Daylights) and Ricky Jay’s ursine techno-geek Henry Gupta, but both are dull as dishwater. Although, Vincent Schiavelli’s cameo as stiffly Teutonic assassin Dr Kaufman is full of dark humour thanks to understatement and faux modesty.

.

.

While Tomorrow delivers some of the best action of the Brosnan era, it also offers some of the silliest. Hands-down, the biggest highlight is the pre-titles sequence, in which our man destroys a Khyber Pass arms bazaar with the weapons of a jet fighter, then flies it and its nuclear torpedoes out of harm’s way seconds before the site’s struck by a British warship’s missile. Finely paced and thrilling, it’s simply one of the best ever Eon openings. There’s also the excellent motorcycle chase through the streets – and buildings and balconies – of Saigon, culminating in the bike’s outstanding jump over a helicopter and the underground car-pack chase in which Bond’s pursued in his remote-controlled BMW 750i car; funny and clever, a pity then it features such a dull vehicle. Less successful, though, is the daft OTT HALO jump (a parachute leap Felix Baumgartner’d proud of) and the climax aboard Carver’s stealth boat. Sure, it’s bombastic, but too much; it’s far too Die Hard for Bond. I mean, why on earth is 007 packing a machine gun in one hand and in the other his new Walther P99 pistol – the latter with its silencer on? Ridiculous. Worth noting here is it was during this flick 007 acquires the P99, ensuring it replaced the PPK as his weapon of choice for the rest of The Brozzer’s reign and up to the end of Casino Royale (2006) – an unsubtle, unnecessary effort to update the Bond brand. Thank goodness the PPK’s now back once more.

They may be less subtle than GoldenEye‘s, but Tomorrow certainly has its moments of humour – many of which tap into the broad comedy of the ’70s Moore era. Take Bond having to ‘pull out’ while brushing up on his little Danish at Oxford or the car-park chase and especially its conclusion that sees 007 ‘return’ the car by crashing it in through the window of an AVIS vehicle rental centre. There’s also a Q scene that sees the latter demonstrate how to remotely drive the BMW (only for Bond to rather ridiculously outdo him) and a scene in which Bond checks out Chinese Intelligence’s latest gadgets in Wai Lin’s Saigon HQ. Less funny though is, as mentioned, Carver’s worst, near toe-curling efforts at humour. Still, at least there’s Kaufman – although quite how Bond’s so quickly able to shrug off the latter’s murder of his one-time love in the film’s second half, during which he’s often just as chipper as ever, is a bit of a mystery.

.

.

Arguably Tomorrow‘s best facet is its music. Scored by composer David Arnold, it’s very much of the John Barry school, boasting full-out orchestral themes, blaring brass, soaring stings and an all-round style that’s the biggest and boldest to soundtrack a Bond film for many a year. Arnold unquestionably positions himself as heir to Barry here (bringing back the stonking electric guitar solo of the Bond Theme as 007 merely coolly walks about and the familiar staccato-like brass cue from Russia), a ploy that pays off big time – not least for him as it landed him the gig for the next four Eon efforts. The score’s probably at its best in White Knight, which accompanies the awesome opening sequence (click above image to hear it), and in the rich, Eastern-esque Kowloon Bay, then shows a different hand – and something of what Arnold would later bring to the table – in the car-park chase-backing Backseat Driver, with its techno-like electronic rhythms (courtesy of Propellerheads’ Alex Gifford). Surely wrongly though, the rather excellent Bassey-esque song Surrender (performed by k.d. Lang and written by Arnold with lyricist Don Black), whose theme nicely appears throughout the score, is shunted to the end titles as Sheryl Crow’s rather drab title song takes centre stage over the opening titles. Not Eon’s finest hour that decision.

Tomorrow is let down by its locations – especially its first half’s major setting. Seriously, what the hell is James Bond doing in Hamburg? I’ve nothing against the place (as a Beatles fan, I’m grateful for the crucial role it plays in their story), but exotic, unique and Bondian it’s not. Sure, its best parts on display here (rather than the parts The Beatles frequented) are handsome, but that shouldn’t be enough for 007. I mean, he might as well have visited either Manchester or Birmingham; both at their best are as handsome as Hamburg. Things pick up in the second half when Bond, Wai Lin and Carver decamp to Saigon. Sadly, though, despite what we’re offered brimming with Eastern flavour, we’re not actually in Vietnam, as the filmmakers deemed it too difficult to film there; instead it’s Bangkok and other bits of Thailand again (previously visited in 1974’s Golden Gun), and, apparently to a surprisingly large extent, mocked-up street scenes shot at Pinewood. A bit of a shame then. In which case, Tomorrow‘s most unusual and best locale may actually be Oxford and its dreaming spires, which we’re in for about 30 seconds.

.

.

Tomorrow doesn’t lack on the gadgets front, but (not unlike other aspects of this film) its devices aren’t exactly the most imaginative. Indeed, the primary gadget is, erm, a mobile phone. Mind you, it does open up to reveal a pad that can be used to remotely-drive the BMW, as well as fire electric sparks that can separately pick door locks and stun assailants with up to 2,000 volts. Wai Lin sports a rather nifty device in the shape of a bangle that doubles as a piton, which she fires into the wall of Carver’s Hamburg HQ, allowing her simply to descend by walking down the wall. Her Saigon base also boasts several gadgets, of course, most of which exist merely for comedy value, though (this scene coming off rather like Bond’s reveal of Holly Godhead’s CIA gadgets in 1979’s Moonraker). But Tomorrow‘s most significant gadget is surely the GPS encoder thing itself. A very clever piece of kit, even if it’s a little difficult to pick up exactly what it does, it’s being stolen by 007 ensures he can locate the real resting place of the Brit warship off the coast of Saigon, somewhat turning the tables on Carver, whom originally used it send the ship off-course.

For the most part, Tomorrow certainly looks good. Taking the ‘heightened reality’ glamour of GoldenEye and running with it, the result’s a very self-confident style informed by a mid- to late ’90s ‘Cool Britannia’ swagger (Bond getting briefed in M’s limousine as, flanked by outriders, it speeds through Westminster; British Navy bods on warships; the classic DB5 cruising through London and Oxford; and Bond’s look itself, dark suits under long, light brown overcoats) and the then rising phenomenon that is the global 24-hour media (as represented by Carver’s empire consisting branded buildings in Hamburg and Saigon, full of TV screens displaying constantly changing images). Palette-wise, the side may be let down a little by the sterile Hamburg and drab BMW saloon cars, but Saigon/ Bangkok throws into the mix welcome colour and exoticism, as well as the unusual sight of 007 in a baggy blue shirt and sneakers following capture by Carver’s goons, which contrasts nicely with the earlier vodka-quaffing, hotel room-residing Bond looking dishevelled but still irresistibly smoother even than a Tony Blair New Labour speech.

.

Adjuster: -2

.

A film of two halves, Tomorrow Never Dies opens as a superior if disappointingly Hamburg-set espionage thriller, flushed with style and ‘realist’ fantasy, but then ups sticks to the Far East where the careful pacing and plotting disappear just as Caver’s face-banner is ripped apart, with the action ramping up to dizzying levels. Rather a missed opportunity then, this Eon effort nonetheless gets the job done competently.

.

.

Best bit: Bond escapes from the Khyber Pass in a jet

Best line: “You always were a cunning linguist, James”

.

.

.

.

.

Directed by: Michael Apted; Produced by: Michael G Wilson and Barbara Broccoli; Screenplay by: Neal Purvis, Robert Wade and Bruce Fierstein – title taken from a passage in the Ian Fleming novel On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963); Starring: Pierce Brosnan, Sophie Marceau, Robert Carlyle, Robbie Coltrane, Judi Dench, Maria Grazia Cucinotta, Goldie, Desmond Llewelyn, John Cleese, Samantha Bond, Michael Kitchen, Colin Salmon, David Calder, Ulrich Thomsen, John Seru and Serena Scott Thomas; Certificate: 12; Country: UK/ USA; Running time: 128 minutes; Colour; Released: November 8 1999; Worldwide box-office: $361.7m (inflation adjusted: $491.6m ~ 14/24*)

.

.

The ‘millennium’ Bond film, The World Is Not Enough fittingly looks back as much as forward – and its plot plays a big role here. Having retrieved a suitcase of money in Bilbao, Bond returns it to its owner, British oil magnate Sir Robert King. Unbeknownst to the latter and 007, the money notes themselves are topped with chemicals that when in proximity with King’s duplicate lapel pin cause an explosion, killing him. Sensing M (an old friend of King) is hiding something, Bond gets it out of her – several years ago King’s daughter Elektra was kidnapped by former KGB killer-turned-terrorist Renard and, rather than pay the ransom, M oversaw a botched operation to rescue her, ensuring an arduous captivity. Bond realises the money ‘returned’ to King was the same amount as the ransom, thus deduces it was stolen and returned by Renard, so Elektra must be in danger again. He’s ordered to ‘shadow’ her in Azerbaijan where she now runs her father’s oil business and eventually learns she turned Renard when in captivity, scheming with him to kill her father and inherit the oil. The pair then kidnap M and hijack a submarine in order to explode its nuclear reactor in Istanbul and destroy a Russian oil route under the Bosphoros, leaving Elektra’s pipeline far more valuable. Aiming for On Her Majesty’s Secret Service-style emotional complexity with turn-of-the-century touches, TWINE‘s narrative is ambitious, but oddly underwhelming.

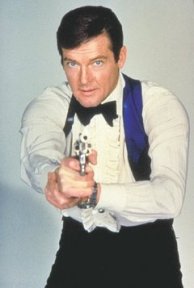

There’s a great drinking game to be played when watching Brosnan’s Bond in TWINE: imbibe whenever he touches his face (especially his lips), walks with a hand in one of his pockets, puts another in his suit jacket (à la Admiral Nelson) or delivers a ‘pain face’ – a letterbox-mouth grimace. Why’s it so good? It gets you plastered. Unlike in GoldenEye and Tomorrow, he noticeably falls back on suave but obvious tics here – ‘Brosnanisms’, if you will – which after more than one viewing tend to diminish his impact. Yet he isn’t alone with this rather soapy acting, practically every one of the flick’s leads are culpable (certainly Marceau and Carlyle), suggesting heavy-handed direction from helmer Michael Apted and melodrama from its scribes. For all this though,The Brozzer’s as smooth, confident and indispensable a presence here as you’d want from a 007 actor. It’s his third effort and, don’t doubt it, he’s definitely James Bond.

.

.

Impressively, Sophie Marceau could be said to be the series’ first lead villainess (although Russia‘s Lotte Lenya aka Rosa Klebb may have something to say about that). And she makes the unique Elektra King memorable – sultry, seductive, egotistical and seemingly driven to psychopathic evil owing to her father and M’s non-attempt to rescue her from Renard years before the events of TWINE. Offering undeniable beauty, charisma and youthful abandon, her quality as a thesp often shines despite the hokey dialogue with which the script lumps her and others. Indeed, this movie’s girls would certainly receive a higher score were its others to get nearer Elektra’s standards. But Denise Richards’ nuclear scientist Dr Christmas Jones is a throwaway Bond Girl. Richards tends to get the brunt of the blame here from the series’ fans, but its more the screenplay’s fault; she’s given little characterisation to work with, coming off as a far more straightforward, bimbo-ish Bond companion than Elektra in the flick’s second half (the tone’s set from her entrance, undressing to reveal a Lara Croft outfit and strutting towards Bond, and moves on little from there). There’s also Maria Grazia Cucinotta’s ‘Cigar Girl’ assassin under Renard’s employ and Serena Scott Thomas’s MI6 medic, the nicely named Dr Molly Warmflash, but both appear only briefly.

While TWINE‘s main baddie is Elektra, lead villainy duties are actually shared with Robert Carlyle’s Renard. The latter’s a missed opportunity. Starting off a chaos-loving, deranged, diminutive git whom seems a nightmare for 007, as soon as it’s apparent Elektra’s the object of his affection (an unusual twist for such a hard-arsed villain) and the brains behind their scheme, he loses his early menace, now a love-lorn freak who’ll do anything for his seductress. Still, he possesses a great bad guy deformity, a bullet lodged in his brain that, while handily and eerily making him impervious to pain, will eventually kill him. A shame then during the submarine-set climax it’s not this that does him in (which surely would have added to the poignant figure he’s become), but a a nuclear bolt launched by Bond into his stomach. Further villains number Ulrich Thomsen’s Davidov, John Seru’s (‘Vulcan’ on ITV’s Gladiators) Gabor and DJ Goldie’s Mr ‘The Bull’ Bullion, a comedic but two-faced sidekick for returning ally Valentin Zukovsky.

.

.