![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

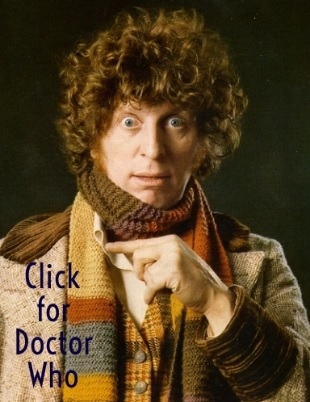

The wanderer returns: a companion-less Fourth Doctor is summoned back to his home planet Gallifrey where he’s embroiled in a devious assassination plot devised by his arch nemesis

Coo, isn’t 2013 flying along? It’s nearly September and feels like it shouldn’t be any later than June. Well, at least that means one thing – yes, peeps, we’re getting ever nearer to the day the greatest sci-fi TV show of all-time Doctor Who (1963-present) marks its golden anniversary.

And, in its comprehensive (nay, time- and space-journeying) celebration of all things Who, this blog offers up the latest in its looks-back at/ reviews of outstanding serials from the show’s past. And this time it’s a big one, all right; the one that not only set in stone the look and feel of The Doc’s world Gallifrey, but also notoriously got Mary Whitehouse’s back up like never before. Deserving of celebration indeed, then ’tis The Deadly Assassin…

.

.

.

Doctor: Tom Baker (The Fourth Doctor)

Villains: Peter Pratt (The Master); Bernard Horsfall (Chancellor Goth)

Allies: George Pravda (Castellan Spandrell); Erik Chitty (Co-ordinator Engin)

Writer: Robert Holmes

Producer: Philip Hinchcliffe

Director: David Maloney

.

.

.

.

.

Season: 14 (third of six serials – four 25-minute-long episodes)

Original broadcast dates: October 30-November 20 1976 (weekly)

Total average viewers: 12.2 million

Previous serial: The Hand Of Fear

Next serial: The Face Of Evil

.

.

.

.

.

Having been summoned back to his home planet Gallifrey and, thus, having been forced to sadly depart from his maybe more-than-fondly-thought-of companion Sarah Jane Smith, The Doctor unwillingly pilots his TARDIS towards his destination, only to have an unpleasant vision – indeed, a premonition of the Gallifreyan President’s murder… by The Doctor himself (see video clip above).

Landing his TARDIS in the Citadel (the capital city that towers into the sky to a point and is the Time Lords’ home), he slips out, but not before leaving a note about his premonition for the security bods he knows will enter his TARDIS to find whom owns it – because, of course, when he left Gallifrey way back when, he borrowed (i.e. stole) the time- and space-ship, ensuring it’s unregistered. He’s almost immediately cornered by a guard, though, only for the latter to be killed by an assailant dressed in black robes.

The Gallifreyan security chief, the level-headed Castellan Sprandrell is angry that the guards have allowed a TARDIS thief – and seemingly the murderer of one of their number – to escape into the capital, while The Doc himself (disguised in the ostentatious ceremonial garb of the Time Lords) finds his way to the Panopticon, the Citadel’s great hall where the resignation of the very President whose ‘murder’ he witnessed/ carried out is about to take place.

Here he converses, albeit evasively, with old classmate Runcible, now a newscaster, who’s covering the event for (one assumes) the equivalent of TV on Gallifrey. As our man chats, he spies across the hall a staser rifle resting next to an unattended camera. Rushing to it now, just as The President steps on to the stage opposite, he takes hold of the rifle, looks through its sights and seemingly shoots the former dead.

The Doc isn’t the assassin, of course – but the odds-on would-be-successor to the deceased President, Chancellor Goth, is sure he is and swiftly holds a trial to determine our hero’s innocence or (more likely, the way it’s going) his guilt. However, the latter has an ace up his sleeve and plays it, for he invokes an article of Gallifreyan law that ensures he’ll have time to prove he isn’t the assassin and find out who is. He declares he’s standing for the Presidency in addition to Goth, which means his sentencing will have to be put on hold until the election is completed. Another Chancellor, Borusa (The Doctor’s old teacher, whom appears to hold a prickly opinion of the latter) acknowledges his former student is within his rights to exploit this loophole in the law and declares he therefore has 24 hours to clear his name.

Through the millennia, the Time Lords of Gallifrey led a life of ordered calm, protected against all threats from lesser civilisations by their great power. But this was to change. Suddenly, and terribly, the Time Lords faced the most dangerous crisis in their long history… ~ The Doctor’s voice-over prologue that opens the first episode

Getting to work quickly, The Doc returns to the Panopticon with Spandrell and his underling Co-ordinator Engin in tow. There, the former points out he wasn’t aiming the staser that he fired at the President, but at the figure whom was surely the real assassin, a chap in black robes The Doctor spied at the last moment. He discovers he was unsuccessful in shooting the assassin, though, because the rifle’s sights are off, which Spandrell confirms, while The Doc also discovers the blast mark in the far wall his staser shot made. Could he be telling the truth? Could somebody be trying to elaborately frame him? Spandrell begins to think it’s a possibility.

Indeed, he believes it even more likely when, just as The Doctor suggests they check the ‘TV’ camera’s barrel (for surely it would have recorded the actual assassin), they hear Runcible scream in terror. He’s discovered the camera barrel is empty of film and in its place is the cameraman – miniaturised. Suddenly, things become much clearer for The Doc; death-by-miniaturising is one of the favourite forms of murder of his sworn enemy, renegade Time Lord The Master. Instantly, having departed to try to find the film, Runcible wheels back towards them, a knife in his back; he dies within in seconds.

Curiously, neither Spandrell nor Engin are aware of The Master’s existence, claiming there’s no record of him in the Matrix – a database that taps into the minds of past ‘saved’ and present ‘living’ minds of every Time Lord, which among other things operates as an effective forecaster of future events. Engin is responsible for maintaining the Matrix and is thus flummoxed, in particular; The Doctor’s adamant however – for The Master to be wiped from it (presumably by his own hand or that of an accomplice enmeshed in the Citadel) there must be another unknown ‘entry point’ into the network, which one of them accessed.

This, The Doc reasons, was why he had a premonition of himself ‘murdering’ the President; it was generated and sent to his mind and then all trace of it deleted along with The Master’s details. There’s nothing for it then, he decides, he must interface – or, essentially, ‘go into’ – the Matrix and find who’s been manipulating it, as the culprit will most likely be the assassin. Spandrell and Engin stress how dangerous this will be, but The Doc won’t be swayed – he has no choice; he has to do it.

Once inside the Matrix, he finds himself in a reality seemingly created and shaped by its interloper, which gives the latter a distinct advantage as a battle of wills takes place between the two. It’s a hostile terrain that, one moment, takes the manner of a sliding, shale-rock-filled quarry and, the next moment, a tropical-like jungle. Outside the Matrix, Spandrell and Engin observe the ‘virtual’ physical trials The Doctor is undergoing (almost being struck by a by-plane, escaping a train within seconds of it running him down and journeying for what feels like miles and miles and hours on hours with an injured, bleeding leg – see bottom video clip) are taking a huge toll on his mind, and fear he may not be able to survive it. There’s a danger too The Master’s accomplice, we discover, we may not make it out of the Matrix alive either, as hiding elsewhere in the Citadel, The Master (the figure in the black robes of before, but now a husk of a humanoid that’s little more than a skeleton) turns up the power with which they’re manipulating the network to maximum, despite the pleading of his unseen accomplice.

The Doctor: What was his plan?

Assassin: [Dying] Couldn’t… fight… his mental dominance. Did everything he asked. Sorry now

The Doctor: What was…

Engin: It’s no use, Doctor

The Doctor: No answer to a straight question. Typical politician

Eventually, The Doctor gains the upper hand in this nightmarish ‘reality’ over his opponent – in the guise of a big-game hunter with a rifle and a netted hood over his face; a hood that the former manages at least to remove – only to discover his enemy (and presumably the assassin) is none other than Goth. A tussle ensues, during which Goth unsuccessfully attempts to ‘drown’ The Doctor in a lake. The manufactured world of the Matrix begins to burn around them and The Doc manages to escape and – only just – regain consciousness. He informs Spandrell and Engin of the assassin’s true identity and they hasten to his and The Master’s lair, having been able now to trace its location via the Matrix.

There the trio discover The Master lifeless and seemingly dead and Goth on the verge of dying, owing to the further power surge pushed into the Matrix and the toll of his ‘mind battle’ with The Doctor. He confesses, having discovered The Master near death (the evil Time Lord at the end of his regeneration cycle of 13 ‘lives’), he brought him back to Gallifrey and devised with him the intricate plan they almost pulled off by which he’d definitely gain the Presidency. Before the other three can learn what The Master would have got out of it, though, Goth slips away, leaving The Doc uneasily feeling The Master surely wouldn’t have accepted ultimate death as easily as it seems he has.

Linking what Goth would practically have gained in assuming The Presidency to what The Master could have gained – the actual seals of office of The President, the ceremonial relics that are the Sash and Rod of Rassilion (the latter being a legendary Time Lord whom original harnessed ‘Time Lord power’ and created Gallifrey’s society), The Doctor learns that it is precisely these two accoutrements that can act as tools to open the Eye of Harmony (the heart of a black hole that Rassilion captured and from which he derived Time Lord power), which lies beneath the Panopticon. Indeed, he and the dignitaries soon discover that The Master has faked his death and stolen the Sash and Rod and, clearly then, wishes to use them to open the Eye in order to jump-start his regeneration cycle – even though doing so will destroy Gallifrey.

Reaching The Master just in time, The Doc wrestles with him, as the entire Citadel begins to shake and start to break up owing to the Eye being opened. Yet, The Master slips and falls through a fissure in the floor and the former is able to close the Eye before the city – and the planet – are destroyed. Accordingly, Borusa (dismayed at all the damage) accepts The Doctor has saved the day, as well as Spandrell’s explanation of how he was framed and who really murdered the President, thus he drops the charges against The Doc so long as he leaves Gallifrey. This our hero is only too happy to do – although Spandrell witnesses a survived Master also fleeing the scene in his own TARDIS, which is disguised as a grandfather clock. Nonetheless, Borusa grudgingly gives The Doctor a mark of ‘nine out of ten’ for his efforts…

.

.

.

Why is The Deadly Assassin such an essential Doctor Who serial? Because it’s utterly unique while, conversely, also fitting very much in the mould of a classic Who story – and does both of these brilliantly, ensuring it’s easily one of the best adventures of The Doc’s long back catalogue of escapades.

First up, distinguishing itself from every other ‘Classic’ serial ever made (and every Doctor Who story ever made apart from – at my count – the late Tennant specials The Next Doctor from 2008 and The Waters Of Mars from 2009), The Deadly Assassin features no companion whatsoever for its protagonist. It boasts allies, sure, in the shape of Spandrell, Engin and to a lesser extent Borusa and Runcible, but as The Doc’s been forced to dump (arguably his greatest ever) companion Sarah Jane at the end of the directly preceding story The Hand Of Fear (1976), as she can’t accompany him to Gallifrey, he has to visit his home planet entirely on his tod. Indeed, this too ensures there’s not even a single human being in any of the story’s four episodes. Another first and only for the series?

It’s something of an experiment, for sure, but as a one-off it works – with TARDIS-like cloister bells on. Caught up in The Master’s near-ingenious murderous scheme, with all its high political machinations, and framed as the killer, at times The Doc’s left more singularly alone than we ever usually see him, emphasising then the trap into which he’s fallen among the people one not versed in what makes him tick would think he’d feel most at home.

Secondly, we have that assassination/ political-underbelly-revealing plot. Like so many from Who‘s ’70s golden age, it was dreamt up by then script editor Robert Holmes (other classics of his being 1975’s The Ark In Space, much of 1975’s Pyramids Of Mars and 1977’s The Talons Of Weng-Chiang). It’s an absolute humdinger, full of thrills, spills and marvellously imaginative ideas (especially the ‘virtual reality’ of the Matrix). The influence of Richard Condon’s iconic brainwashed-assassin-themed novel The Manchurian Candidate (1959) – and its subsequent, equally iconic 1962 Hollywood adaptation – is clear to see to any fan of US literature and cinema, yet Holmes does far more than turn out a sci-fi take on a cultural classic of political corruption gone wild.

Fusing wit and irony to the proceedings throughout, in Assassin he and director David Maloney arguably don’t give us a fascinating (and smartly constructed) window on to the running of Gallifrey’s Time Lord society, but instead deconstruct the whole thing as they show it to us, gently satirsing the everyday oneupmanships, frippery, corruption and cover-ups that take place in governments and the running of powerful states.

If you doubt that, consider Borusa’s starched, unyieldingly (supposedly) upstanding demeanour at the end despite all that’s happened and his unchanged attitude to The Doctor, Runcible’s smug reaction to our man’s black sheep-like return to the fold in spite of the former being merely an establishment-connected TV presenter and the general slow, lumbering, ceremonial-filled, millennia-old ways of Gallifreyan society. The Deadly Assassin has as much in common with Yes Minister (1980-84) and Yes Prime Minister (1986-88) or the humour of a top sketch from That Was The Week That Was (1961-63) as it does with, say, Inferno (1970) or The Dæmons (1971).

Yes, all right, there are two or three quibbles. The otherwise gloriously OTT Time Lord costumes look a little too plastic (and sadly cheap) not to be distracting, The Doctor himself surrenders his overcoat, hat and – sacrilege! – scarf throughout (although this just emphasises the serial’s difference and its different treatment of the character, plus he looks pretty cool in just his white shirt and burgundy bottoms) and, of course, the story’s title itself is an example of monstrous tautology, yet ultimately these points simply can’t detract from Assassin‘s unquestioned quality and iconoclasm.

.

.

.

.

.

As mentioned above, Assassin‘s status as an experiment of a Who story is no exaggeration – apparently Baker had suggested to mid-’70s era producer Philip Hinchcliffe that, upon Elisabeth Sladen‘s departure from the series, the show – and maybe more specifically he – could go it alone without a companion and change the thing from a two- to a one-hander drama.

Oddly, given the terrific thing the serial turned out to be (yet, for the sake of the show to come, it was surely the right decision), Hinchcliffe deemed the result mixed and the idea of Baker leading the show alone not to be its future – maybe he could envisage the perhaps excessive artistic influence Baker might wield in the years to come? Although, maybe a bigger concern was that Holmes had actually found it especially challenging to write a story in which The Doctor had no companion to bounce thoughts, ideas and plans off – the essential role, one might argue, of his companion. Louise Jameson made her debut as The Fourth Doc’s new companion Leela in the following story, The Face Of Evil (1976).

This serial too, lest we forget, marked the height of ‘TV standards’ campaigner (read: media prude extraordinaire) Mary Whitehouse’s obsession with Doctor Who. The cliffhanger at the end of the third episode (in which Goth holds The Doc’s head underwater attempting to drown him) was the moment that broke the camel’s back for her; she claimed children could be damaged by it as they wouldn’t know whether he’d survived it for at least a week – although the show had been offering up cliffhangers of that exact nature for years. What was new about it perhaps, was it’s visceral nature – it’s seen been cited a classic exemplar of the Hichcliffe/ Holmes old-school horror/ terror-influenced era.

A particularly intriguing point cast-wise concerns Bernard Horsfall, whom played The Master’s stooge Goth. Outside of Who, he’s maybe best recalled as 007’s ill-fated MI6 colleague in the George Lazenby-starring Bond film On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969); inside Who, he’d previously appeared in the serials The Mind Robber (1968), in which he portrayed Lemuel Gulliver, The War Games (1969) and Planet of the Daleks (1973). In the second of those two stories he also played a Time Lord, whom because he’s unnamed, many have suggested may be Goth in younger years – probably not, but it’s interesting to speculate.

Elsewhere, following the sadly premature death of the great Roger Delgado, the role of The Master (in a very different guise to that of Delgado’s goatee-bearded, devilish smoothie) was taken by Peter Pratt, a thesp famed for his stage roles, especially Gilbert and Sullivan operas, while Czech actor George Pravda (Spandrell) also appeared in the Bond film Thunderball (1965) as an Eastern European scientist.

Aside from Baker, none of Assassin‘s thesps would appear in the show again, but their characters would. Angus McKay’s Borusa cropped up again at the end of the following series in the also Gallifrey-set The Time Warrior (1977), as well as in Arc Of Infinity (1983) and, most notably of all, in the 30th anniversary-celebrating special The Five Doctors (1983) – although in these three serials the character was played by John Arnatt, Leonard Sachs and Philip Latham respectively. Just like Borusa, the Time Lord society (its disciplined dedication to its stuffy traditions, its lofty stand-above-it-all attitude to the universe, its political machinations and its look as established in Assassin) was to appear over and again in the ‘Classic’ series and eventually in the ‘timelocked’-era of the ‘NuWho’ The End Of Time specials (2009-10).

The very model for Gallifrey then was established – and has never better presented than – in The Deadly Assassin. No question, few stories in the show’s history have looked through the sights and pulled the trigger as well as this Gallifreyan juggernaut.

.

.

.

Next time: The Talons Of Weng-Chiang (Season 14/ 1977)

.

Previous close-ups/ reviews:

Pyramids Of Mars (Season 13/ 1975/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

Genesis Of The Daleks (Season 12/ 1975/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

The Ark In Space (Season 12/ 1975/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

The Dæmons (Season 8/ 1971/ Doctor: Jon Pertwee)

Inferno (Season 7/ 1970/ Doctor: Jon Pertwee)

The War Games (Season 6/ 1969/ Doctor: Patrick Troughton)

An Unearthly Child (Season 1/ 1963/ Doctor: William Hartnell)

.

Purrfectly pink/ Diamond geysers? The Pink Panther (1963)/ A Shot In The Dark (1964) ~ Reviews

.

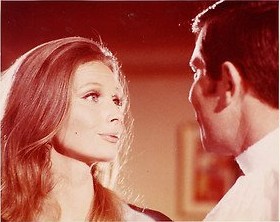

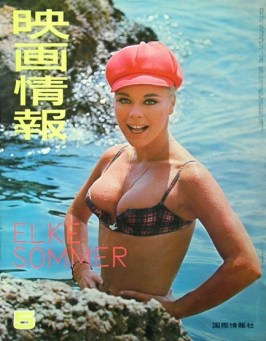

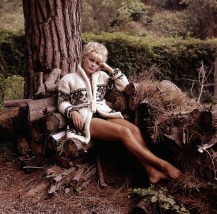

A few weeks ago, I kicked-off (yet) a(nother) ‘summer season special’ here at George’s Journal in the shape of a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the not to be underestimated, mostly very funny Pink Panther comedy film series – and have punctuated it since with a couple of pictorial-based posts dedicated to the beauty of four of its female co-stars Capucine/ Claudia Cardinale and Elke Sommer/ Catherine Schell. Now, however, it’s time to take that blog season by the Clouseau-esque trenchcoat lapels and really get it properly going with my thoughts on (i.e. reviews of) the first pair of Pink Panther movies – the one, the only (well, actually, the first and original) The Pink Panther and it’s direct sequel A Shot In The Dark. Cue Henry Mancini…

.

(The Pink Panther) Directed by: Blake Edwards; Starring: David Niven, Peter Sellers, Capucine, Claudia Cardinale, Robert Wagner, Colin Gordon, John Le Mesurier and Fran Jeffries; Screenplay by: Blake Edwards and Maurice Richlin; US; 110 minutes; Colour; Certificate: PG

.

A cynic might say the funniest thing about The Pink Panther is that of all The Pink Panther films it’s the least ‘Pink Panther’ film. Personally, I’d probably put it in more conciliatory terms: although not as laugh-packed as most of its succeedents, the first in the universally known comedy blockbuster series is unlike many of the others, its charms arguably being more unexpected and, in a way, more intriguing.

Distinguishable from its wholly Peter Sellers-fronted, mostly slapstick-fuelled sequels, The Pink Panther is actually a smooth, luxuriant, Euro-exotic crime caper that was intended as a star-vehicle for the talents of the debonair David Niven as charming rake Sir Charles Lytton (who’s secretly jewel thief extraordinaire ‘The Phantom’), but of course the movie was stolen by supporting player Peter Sellers as the hapless Inspector Jacques Clouseau of the French Sûreté, who’s tasked with tracking down the former – whom vainly always leaves a white silk glove engraved with a capital ‘P’ at the scene of his crimes – when its assumed he’ll attempt to steal the most expensive diamond in the world, the ‘Pink Panther’, from its owner the gorgeous Princess Dala (Claudia Cardinale) of the fictional Lugash colony, as she visits the exclusive ski resort of Cortina d’Ampezzo.

The film then has arguably more in common with glamorous Hollywood capers of the ’50s and ’60s like To Catch A Thief (1956), Charade (1963) and Topkapi (1964) than the other Pink Panther flicks. Taking a cue from the urbane persona of Niven himself, much of its tone and pacing is relaxed; the photography only too happy to languidly make the most of the Alpine locations, while the slow-tempo action’s perfectly accompanied by Henry Mancini‘s score, oozing classy, jazzy melodies and motifs. Indeed, at one point an entire scene’s given over – far from unpleasantly, though – to a performance by singer Fran Jeffries of the Mancini/ Johnny Mercer song name-checked in the movie’s iconically animated opening titles, Meglio Stasera (It Had Better Be Tonight).

And things are so relaxed, at other times they’re even horizontal – in one scene mid-way through, Dala lies prostrate on a tiger-skin rug getting plastered on champagne as Niven’s Lytton attempts to seduce her (so he may get his mits on the diamond), but it’s such a slow carry-on – especially the by-play – it’s maybe not surprising the seduction doesn’t work at all. More critically, the movie’s two major set-pieces – a costume party at which the diamond’s theft and its thief’s capture are finally attempted and a subsequent multi-car chase through the night-time streets of Rome – both suffer from a lack of haste.

Yet, what elevates The Pink Panther into something truly memorable (and a huge box-office hit back in the day) is the presence of Sellers, of course. Clouseau may only be in his genesis here (he plays a violin dreadfully rather than executing the karate chops and leaps to come), yet he’s already a wonderful creation of Buster Keaton-like big screen buffoonery. For instance, thanks to his inexplicable insistence on wearing a medieval knight’s suit of armour at the aforementioned costume party, his clanking about the shop, not being able to see where he’s going at all (as his visor keeps clanging shut), imbues the sequence with enough hilarity to more than save it.

Indeed, it’s his exaggerated facial expressions, pratfalls, misunderstandings and general incompetence that make the film – it’s faster and simply funnier when he’s on-screen and less satisfying when he’s not, even with the presence of fellow supporting actors Capucine (on fine comic form as his wife Simone, whom unbeknownst to him’s in total cahoots with Lytton) and an exceedingly young Robert Wagner as Lytton’s tearaway nephew George, whose inclusion, it must be said, unnecessarily complicates the plot.

Ultimately then, The Pink Panther is more a curate’s egg than a solid entry in the enduringly popular film series it spawned, being – as pointed out – really rather dissimilar to the entries that followed it. Yet, when it sprouts wings and flies, it truly does (just like the series’ other entries) and when it does so it’s with two classic Pink Panther film facets – first, the opening titles that introduce both the DePatie-Freleng cartoon Pink Panther and Mancini’s instantly recognisable theme and, second, the movie’s most satisfying and best slapstick sequence, which sees Clouseau and his wife prepare for bed while the latter tries to dispel the amorous Lytton and then the randy George from the hotel room without her husband noticing. Somewhere along the line a bottle of champagne accidentally erupts; just like the scene itself, it’s explosive, delightful and hilarious.

.

.

.

.

.

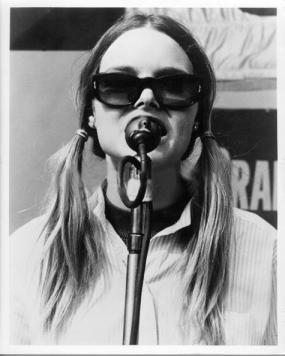

(A Shot In The Dark) Directed by: Blake Edwards; Starring: Peter Sellers, Elke Sommer, Herbert Lom, George Sanders, Tracy Reed, Burt Kwouk, Graham Stark and André Maranne; Screenplay by: Blake Edwards and William Peter Blatty; US; 102 minutes; Colour; Certificate: PG

.

One uninitiated into all things Pink Panther might be fooled on first viewing A Shot In The Dark, going away with the impression it was the first in the series. It wasn’t, of course (as the above review and my other posts in this PP season very much attest), but it was with this follow-up flick (coming just months after the original’s release) that the ‘Pink Panther film’ really got going, really found its identity, truly connected with the public; in short, got its mojo.

Ironically, owing to the fact it neither features the words ‘Pink Panther’ in its title, nor the eponymous diamond or ‘The Phantom’ character in its plot, Shot could be said actually not to be a Pink Panther movie; however, that’s just technicalities. For so many tenets of the series were established in this picture: Clouseau (Sellers) taking centre-stage, adopting his ‘reedeeculoos’ French accent, his trademark trenchcoat and tweed trilby and somehow attracting and maintaining a gorgeous female love interest (Elke Sommer‘s lovely Maria Gambrelli); the introduction of Herbert Lom’s utterly marvellous Sûreté superior officer, Chief Inspector Dreyfus, and his murder-causing insane hatred of his hapless inferior; plus, of course Burt Kwouk’s mad manservant Cato, whom never misses a chance to put his employer Clouseau through his karate training paces – at any time, at any place.

Based on a French play adapted for the US stage, it was initially scripted by William Peter Blatty (who’d achieve absolute pay-dirt status nine years later when his screenplay of his own novel The Exorcist was turned into the notorious monster horror hit), on which Blake Edwards started collaborating as he was completing the first Pink Panther flick. The plot then, ostensibly a whodunnit, sees the seemingly useless Clouseau mis-assigned to a murder case at the manor house of a Parisian aristocrat (an as ever über-urbane George Sanders), for which his beautiful, possibly nymphomaniac maid (Sommer) is the chief suspect – so much so anyone in their right mind can’t see any scenario in which she couldn’t be the killer. Except Clouseau, of course, because he’s immediately fallen head over heels for her, and makes it his mission to prove her innocence, in spite of mounting corpses and his own incompetence.

Quality-wise, Shot is easily the best Pink Panther film. Its tight, witty, accomplished plotting ensures it stands out among its fellow Clouseau-featuring capers. And, while there’s the usual slapstick sequences (more than in The Pink Panther, less than in the later series entries), they’re carefully conceived and expertly realised – and most of them unexpected. We have Clouseau’s ridiculous attempts to go undercover and monitor Ms Gambrelli that repetitively get him arrested, then the pair going on a night of dates at each venue of which someone’s bumped off by accident instead of the intended target, Clouseau, and best of all, our hero following his would-be-lover to a location that he discovers all too late is a nudist camp – a sequence that builds to a crescendo of them both trapped in the nuddy in a very busy Parisian traffic jam.

Much credit must go to director Edwards. Already a dab-hand at helming films with smart, sassy humour and physical comedy (1959’s Operation Petticoat and 1961’s Breakfast At Tiffany’s), he dials down the aspirational, glamorous style and tone of The Pink Panther and ups the character-driven comedy and slapstick to suit his upgraded star Sellers – or, more specifically, the latter’s genius character. It’s true that, like its predecessor, Shot‘s certainly a glossy piece of work (more so than the ’70s Pink Panthers, which look and feel very much of that decade), but being a detective comedy based around a manor house, the exoticism of the previous film is gone and, in its place, there’s far more Clouseau and far more gags that land – indeed, many of them positively zing, both visual and verbal (“Give me ten men like Clouseau and I could destroy the world”/ “Look at that, I have Africa all over my hand”/ “François, I just cut off my thumb”).

In the end, though, it’s hard not to suggest the lion’s share of Shot‘s effectiveness – and deserved success (it outgrossed the box-office big-hitter itself that was The Pink Panther) is down to Sellers. If the first film was his US break-out flick, it was this one that made him a Hollywood star and Clouseau a comedy icon. Proof can be found by looking no further than the confusion his mis-pronunciation of the word ‘moths’ (‘meuths’) causes George Sanders’ Monsieur Ballon – even though, despite Ballon having a slight French accent contrasted with Clouseau’s over exaggerated one, they’re both supposed to be speaking in French, so why doesn’t he understand him? It’s a gag that defies the logic of its movie’s universe, yet because it’s so brilliantly executed it doesn’t matter a jot; in fact, it’s wonderful fun that simply washes over the highly entertained audience. Much like the movie itself, you might conclewwwd. I mean, conclude.

.

.

.

.

Talent…

.

… These are the lovely ladies and gorgeous girls of eras gone by whose beauty, ability, electricity and all-round x-appeal deserve celebration and – ahem – salivation here at George’s Journal…

.

Yes, just a few short weeks ago this blog’s Talent hall of fame welcomed to its loving bosom the delights that are Claudia Cardinale and Capucine and, as this corner of the ‘Net’s 50th anniversary celebrations of all things Pink Panther continue (following too its guide to the phenomenon that’s the cinematic and cartoon caboodle itself), its now time indeed to welcome another offering of Euro crumpet deluxe from that classic comic film series into these hallowed totty surrounds. In which case then, let’s – each and every one of us – pay due deference to the delectable Elke Sommer and the sensational Catherine Schell…

.

Profiles

Names: Elke von Scheltz (Elke Sommer)/ Katherina Freiin Schell von Bauschlott (Catherine Schell)

Nationalities: German/ Hungarian (now naturalised British)

Professions: Actress, model, singer and painter/ Actress

Born: November 5 1940, Spandau, Berlin/ July 17 1944, Budapest

Height: Both 5ft 7in

Known for: Elke – her Hollywood breakthrough role as delectable maid and chief murder suspect Maria Gambrelli opposite Peter Sellers‘ Clouseau in A Shot In The Dark (1964). She went on to win the most Promising Newcomer Golden Globe award for her role in The Prize (1964) and had further starring roles in the caperish romantic comedies that were 1965’s The Art Of Love (with James Garner and Dick Van Dyke), 1966’s The Oscar (with Stephen Boyd, Jill St. John and Tony Bennett), 1966’s Boy, Did I Get The Wrong Number! (with Bob Hope) and the Bond-inspired spoofy adventures 1967’s Deadlier Than The Male and The 1969’s The Wrecking Crew (the latter with Dean Martin). As soon as she hit American screens she became sex symbol, gracing Playboy magazine pictorials twice – in ’64 and ’67. Memorably, she appeared in the bawdy caravan holiday-themed Carry On Behind (1975) and also recorded several albums. In later life she’s taken up painting.

Catherine – appearing as the female lead Lady Claudia Lytton (and trying not to corpse in every scene) opposite Sellers in The Return Of The Pink Panther (1975), as well as playing Nancy, one of Blofeld’s ‘Angels of Death’ in the James Bond film On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969). Following her foray into big-budget film series, she spent much of the ’70s gracing the British small-screen with her inimitable class and beauty. Most memorably she was the shape-shifting yet bit-of-all-right alien Maya in Gerry Anderson’s Space 1999 (1975-77) and the villainess Countess Scarlioni in the all-time classic Doctor Who serial City Of Death (1979). She also had roles in a handful of top Brit drama series, including The Onedin Line (1971-80), The Persuaders! (1971), The Sweeney (1975-78), Bergerac (1981-91), Howard’s Way (1985-90) and Lovejoy (1986-94).

Strange but true: Although the daughter of a Lutheran priest, Elke is actually of noble birth and is ‘properly’ addressed as a baroness, being able to trace her family back the 13th century; tragically, when younger she endured three miscarriages and in 1993 saw a nine-year feud with Zsa Zsa Gabor culminate in a $3.3 million libel pay out. Coincidentally, Catherine is also descended from European nobility (the ‘von Bauschlott’ part of her name refers to the region of Germany where her family originated from), ensuring through a great-grandfather she is related to the ‘Sun King’ himself, Louis IX of France (1638-1715).

Peak of fitness: Elke – aside, rather obviously, from those Playboy pictorials, it’s got to be wearing that white bikini in those publicity shots for and actually on-screen in Deadlier Than The Male/ Catherine – in and especially out of her space suit in the little-seen, cult Hammer-produced sci-fi effort Moon Zero Two (1969) – see below…

.

.

CLICK on images for full-size

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Gordon’s alive? Flash Gordon (1980)/ Flash Gordon: the novelisation (Arthur Byron Cover) ~ Reviews

.

(Flash Gordon)

Directed by: Mike Hodges; Starring: Sam J Jones, Melody Anderson, Max von Sydow, Ornella Muti, Topol, Timothy Dalton, Brian Blessed, Peter Wyngarde, Mariangela Melato and Richard O’Brien; Screenplay by: Lorenzo Semple Jr; US/ UK; 111 minutes; Colour; Certificate: PG

.

King Solomon’s Mines (1985). Legend (1985). Return To Oz (1985). Howard The Duck (1986). The Lost Boys (1987). Young Einstein (1988). There’s nothing quite like an ’80s cult fantasy movie, is there? Often trite, almost always camp and usually fairly rubbish, they tend to be box-office bombs the size of Fatman or Little Boy (unlike the now culty but then big earners of their era like, say, 1985’s The Goonies and St. Elmo’s Fire or even 1986’s Ferris Bueller) and utterly derided by critics on release. Yet nowadays they’re swathed in a warm glow of fanboy goodwill. And why not? They’re all rather delightful. As is another of their number, namely the irrepressibly legendary sci-fier Flash Gordon.

Indeed, Flash Gordon neither troubled the cinematic competition (it ended up down in 23rd place on 1980’s US box-office chart), nor did the critics approve – most seeing it less a flash in the pan as deserving of being flushed down the crapper. But, prior to release, it certainly had everything going for it.

For it was brought to the screen by legendary producer Dino De Laurentiis (1968’s Barbarella, 1973’s Serpico, 1984’s Dune and 1986’s Blue Velvet), scripted by Hollywood heavyweight scribe Lorenzo Semple Jr (1973’s Papillon, 1975’s The Parallax View and 1976’s Three Days Of The Condor ), photographed by versatile Brit DOP Gilbert Taylor (1964’s A Hard Day’s Night and Dr Strangelove and 1977’s Star Wars), scored by The Snowman‘s (1982) Howard Blake – along with, of course, the iconic theme from rock gods Queen – and, in a surprising move, helmed by top Brit director Mike Hodges (1971’s Get Carter, 1972’s Pulp and 1998’s Croupier). Unquestionably quite a list, but then, take a gander at the cast…

Heavyweight Swedish thesp and Ingmar Bergman fave Max von Sydow as dastardly despotic alien Ming the Merciless of Mongo; equally as legendary Topol, Fiddler On The Roof star on both stage and screen (1971) and Bond film ally of For Your Eyes Only (1981), as crackpot genius scientist Dr Hans Zarkov; classical actor extraordinaire and future 007 Timothy Dalton as lugubrious woodland world ruler Prince Barin; foghorn-mouthed eccentric actor Brian Blessed as winged Birdman world leader Prince Vultan; velvet-voiced Jason King (1971-72) smoothie Peter Wyngarde as Ming’s cyborg security chief Klytus; respected Italian actress Mariangela Melato as Klytus’s second-in-command Kala; The Rocky Horror Show creator and future host of yuppies-play-games TV show The Crystal Maze (1990-95) Richard O’Brien as Barin’s minion Fico; Italian screen sexpot-on-the-rise Ornella Muti as Ming’s lusty daughter and Barin’s lover Princess Aura and, finally, relative newcomers Melody Anderson and Sam J Jones as heroine and hero, respectively, travel agent Dale Arden and, of course, American football star and saver-of-the-universe-to-be Flash Gordon. Truly, there’s probably not a movie of the ’80s that boasts a cast as eclectic or – 30 years-plus later – as legendary as this. It’s a fortuitous retro wonder.

.

Touchy Topol: “Look at me like that, Ming, and I’ll break your nose; just like I did this bloke’s!”

Not totally like the film itself sadly. Now, don’t get me wrong, there’s much, much about Flash Gordon to love; but there’s a fair deal that, frankly, at times drags it right down into that Arborian swamp with the humanoid-eating spider monster-thing. First, though, the positives. Along with the fabulously groovy casting, maybe what’s best about the flick is its faithfulness to its source material and its realisation of it. The whole shebang originated as a 1930s US comic strip conceived by Alex Raymond, full of flamboyant colour, design and costumes, in which its all-American hero is transported along with knockout beauty Dale Arden – against their wishes – by nutty Zarkov to the planetary system of Mongo, which is ruled with an iron fist by near-supernaturally powerful Ming, and where Flash and his allies team up with the suppliant planets’ rulers (Barin, Vultan et al) to overthrow the despicable tyrant.

Not only does the movie take this fine sci-fi fantasy premise as its plot and run with it smartly and cannily (Aura aids Flash because she wants to shag him; Barin’s jealous of him and only teams up with him when he discovers ‘humanity’), amusingly and wittily (Dale exclaiming comic-strip-esque: “Flash, I love you, but we only have 14 hours to save the Earth!”), but also uses the style of Raymond’s strips as less a touchstone, more a flag-bearer for its look. Unquestionably, the gaudy, primary-toned Mongo (all bold reds, glittering golds, imperial greens and shimmering azures) and the pointed shoulder-pads, knee-length boots and slinky-Arabian-harem-almost-there costumes, as well as the alt-fantasy-esque bulky rocket-cycles and blimp-shaped spaceships (all of which seem to sport phallic points) are a feast for the eyes. It’s almost as if the characters of Dynasty (1981-89) have travelled to the most luxuriant brothel in the universe. A journey to the campest forbidden planet you can imagine.

Unfortunately, though, the camp doesn’t end there. And it’s that which is Flash Gordon‘s undoing at times. As well as what makes it utterly, cultily delightful at the same time, to be fair. It’s all or nothing with this flick; nothing’s done by half. While that works with, say, Queen’s awesome, theatrically bombastic, chart-friendly title song over the magnificent Raymond comic strip-referencing opening titles (see video clip below), elsewhere a little more subtlety wouldn’t go amiss. But with the – let’s be honest, often in their screen careers, enthusiastically thesping – Topol, Dalton (“Freeze, you bloody bastards!”) and Blessed (“DIIIIVE!“/ “Gordon’s alive?!“) only too eager to chew the scenery and the fact that this is a movie featuring men with giant wings who fly, foes battle each other on incredibly cool but overtly dramatic tilting discs featuring rising spikes and Richard O’Brien sits in trees playing pipes, it all gets a bit too pantomime for its own good. A bit like Moulin Rouge! (2001). Only in space.

Ironically, the most subtlety comes from the most eye-catching character, Ming. Under all his ostentatious yet brilliant make-up and costumes, von Sydow brings a highly effective quiet terror and ruthlessness to proceedings, stealing every scene he’s in – even those featuring Blessed. By contrast, his antithesis and humanity’s saviour Flash himself is disappointingly one-note; Dolph Lundgren-lookalike Sam J Jones probably wasn’t helped by the fact he was entirely dubbed and the script does him few favours – but then, that doesn’t hold back Melody Anderson’s memorably spunky and resourceful Dale, who’s almost as sexy as the ludicrously appealing Muti as Aura.

In the end, though, as pretty much elucidated above, criticising Flash Gordon for its faults as a movie sort of misses the point – it’s delicious entertainment for precisely the reason it’s camp as hell and, well, crap as you like. The saying goes that you can’t polish a turd, but few of ’em come as polished or as fun as this synth-and-drum-backed, garish, star-packed Mongo mash classic of its (own) kind.

.

.

.

.

(Flash Gordon: the novelisation)

Author: Arthur Byron Cover

Year: 1980

Publisher: Jove Publications

ISBN: 0515058483 /9780515058482

.

Trust me, my blog-friendly friends, there’s only one way to top the über-campy, culty, delightfully naff fantasy sci-fi experience that’s watching Flash Gordon, and that’s by reading its novelisation. Quite simply, this book genuinely delivers everything the film does, only more; and that, depending on your viewpoint, is likely either laughably bad or wonderfully brilliant – or both.

For one thing – as usual when it comes to novelisations of movies or novels on which movies are based – there’s more characterisation, principally of the protagonists. In surely an improvement on the flick, we’re given both an in-depth look at hero Flash’s psychosis and his back-story. Admirably, the Flash of the novelisation is a far more intellectual, soulful and learned chap than the cinematic Flash is allowed/ has enough room to be. Here the guy’s a pseudo-philosopher masquerading as a football star (no really), for whom being a world famous sportsman’s something of a burden, as are the moments of melancholic solitude his psychological make-up requires him to experience and his inability (superhero-esque) to give his emotional all in an amorous relationship, or so he believes until he meets the delectable Dale Arden and immediately falls for her.

Almost as intriguingly, while the much more down-to-earth Dale is certainly be the tough cookie of the movie, her preponderance for satisfying sex is more than hinted at, thus why Ming’s discovery of her lustiness is what draws him to her so fundamentally and why he desires her as a concubine (a facet of Dale’s character that’s only partially explored in the family-friendly flick). As for Ming himself, well, pleasingly the alien tyrant is afforded a decent amount of detailed characterisation. Most interesting is the attempt to explain how he has some sort of telepathic/ supernatural connection to his despotic ancestors via meditation (which he performs instead of sleeping) and which sort of sustains the force of his will over his servile subjects. Sort of.

And here we come to the drawback of Arthur Byron Cover’s writing – or, as suggested, its savourable delight – namely, the writing style. Now, methinks it’s fair to say that if you’ve sampled any comic books at all, you’ll have noted their frippery of capes, super-powers, semi-eroticism and pantomimic villainy are more than often treated with daft seriousness, even sombre world-weariness.

.

Blessed warning: “Careful you don’t spike your crown jewels, Timbo; you’ll need them as 007!”

And, undeniably and understandably, taking his cue from this (no doubt owing to the comic book origins of his subject matter), Cover lays it on as thick as a slab of thick marmalade with extra orange peel. No impressive adjective is avoided; no dynamic verb disregarded; no excitable adverb omitted. The result is a English primary school teacher’s wet-dream; almost every sentence one a creative writing course tutor might suggest ‘could be toned it down a bit’. Consider this description of Ming’s meditative technique:

‘Ming the Merciless felt valuable insights verging on forbidden knowledge merge with his soul. For moments which stretched until time was a meaningless concept, Ming lay floating, experiencing the peace his turbulent emotions denied him, discovering the nuances of existence overwhelmed by his burdensome ennui‘.

Like i said, though, given the subject matter, there’s a greatness to writing in this everything-and-the-kitchen-sink-like style; Cover clearly knows his sci-fi/ comic book-loving audience so utterly goes for it, and if you’re up for the ride it’s a hell of a lot of fun. Indeed, delightfully it also infects the dialogue; Prince Barin observes of our unique, near-perfect hero to an acolyte: ‘If other Americans are like him, they’re the most dangerous breed of men in the cosmos‘. Coming out as this book did in the early ’80s, Ronald Reagan would’ve probably loved that line.

Still, there’s no question Cover knows exactly what he’s doing. Both a comic book writer and a published fantasy fiction author for several decades, who’s to question what he does here when he’s been a success in this genre for so long? After all, even if the ‘overdone’ style becomes a little tiresome at points, there’s no doubt he brings the universe of Mongo (its constituent worlds included) to life effectively and once Flash, Dale and the similarly invested-in Zarkov blast-off in the latter’s rocket, the pace and action never let up.

Admittedly, there’s practically no resolution following the climax, but then there isn’t in the movie (and thus probably wasn’t in the script from which Cover wrote his book from) and that could well be because of the Ming-tastic teaser both leave us with in the very last reel/ the last paragraph – intended, of course, to set up a sequel. A pity, indeed then, that we didn’t get the chance to revisit Mongo on-screen and in-print for that sequel. Hmmm, or on second thoughts, maybe one of both really was enough – or, to put it another way, thanks for the rocket-cycle ride, Flash, but now it’s time to return to terra firma.

.

.

Tardis Party/ Legends: Tom Baker ~ Top of The Docs

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Pen pal: Tom Baker is in his element (and in his full Doctor togs) as he’s mobbed by autograph hunters while on a mid-’70s promotional walkabout for the greatest ever sci-fi TV show

That crazy curly hair. That inexplicably silly, goofy grin. Those bulging, dazzling eyes. Those deep, sonorous, unmistakable bass tones. That imposingly tall frame. That brown, often crumpled fedora. And, of course, that ludicrously long, multicolour-striped scarf. It could only be – and, of course, is – the fourth and surely forever greatest protagonist of the greatest ever sci-fi show to have graced our TV screens, Doctor Who (1963-present). Yes, it’s the legend in his own ’70s BBC Saturday teatime (and his own lifetime), the one, the only Tom Baker. And for that reason, he is quite TARDIS-tastically the latest entry into this blog’s Legends hall of fame.

Although, if I’m being perfectly honest, while The ‘Baker’s status as The Daddy of Doctor Who rightly makes this post the centrepiece of George’s Journal‘s trawl through 50 years of the show in celebration of its golden anniversary, his synonymosity as the Who Doctor doesn’t define the man on its own. It may be what made him a thespian superstar, a British (nay, international) institution, and thus plays a huge role in the Baker story, but that story isn’t just about Who. There’s certainly more besides – if you will, more time and space outside the TARDIS for him as well as in it.

Indeed, nowadays in his homeland of Blighty he’s as perceived by the media and the public as a barrel-chested, white-haired, jolly, old fully-fledged eccentric as much as he is as a one-time terrific Doctor. It’s a role he seems only too happy with too – just how much he’s playing up to it and how much of it is, well, genuinely him is near impossible to discern, so nobody seems to bother to try. But where does this true/ faux eccentricity come from? What made Tom Baker first The Doctor and then the post-Doctor Tom Baker? Well, it’s been a twisty-turny (nay, wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey) journey has been The ‘Baker’s, involving austerity, awards, Catholicism, depression, marriages and eventual iconoclasm, which once learnt can only persuade the reader he was never going to be anyone else.

His journey started on January 20 1934 in Scotland Road, Liverpool; five years before the outbreak of World War Two and several years before the same city would spawn its four most famous sons in the shape of The Beatles. Thomas Stewart Baker was born into a decidedly working class home, which during the war years numbered as many as 14 people and was infested by cockroaches – leading him to fantasise it being hit by a bomb and him becoming an orphan.

The family was headed by his barmaid and cleaner mother Mary and his father John; its nominal figurehead, a sailor whom, even when in town, seemed not to be at home as much as he could have been. In fact, the lack of closeness between Baker and his dad is perhaps best summed up by the fact the latter once proposed giving his son to a childless couple in Australia, much to Mrs Baker’s consternation – whom cuffed Tom for saying he’d be happy to go.

Thanks to his mother’s religious fervour, Catholicism and its seductive rituals hung heavy over Baker’s childhood. He’s claimed he was near bewitched by the heavy spirituality of the Catholic faith; the blessing afforded his grandmother on her deathbed, her ablaze with wonder and delight at passing over into the next realm, was a profound highlight for him. Although the wicked, irreverent side of Baker was present early on too – a chance weeping due to the cold while an altar boy at a funeral saw him receive two shillings from an adult mourner, only for him to take advantage of more sympathetic souls and turning a healthy profit by play-acting tears at subsequent funerals.

.

From zero to hero (via a villain): a young Baker (l), Golden Globe-nominated as Rasputin in Nicholas and Alexandra (m) and with Elisabeth Sladen at his announcement as the new Who (r)

Nevertheless, his upbringing led him (in his mother’s eyes certainly, no doubt) to making an inevitable step – at the tender age of just 15 he left Merseyside for The Order of Ploermel on Jersey, where he joined its brothers first as a noviciate and eventually became a monk in Shropshire. In a 1974 article from Films Illustrated magazine, Baker opined: “It was difficult to break the pattern of my childhood. I consider that an achievement. Not because I didn’t like it, but because I wanted to do something else other than grow up in that city and do something unskilled, because that’s what would have happened to me”.

Shaven-headed, woken at 4.30 every morning, praying constantly and only allowed to speak occasionally – and then only for conversations about The New Testament – his life had become stricter and more religious than ever. Apparently, touching other human beings was forbidden as was looking into others’ eyes and even smiling. Eventually it became to much for him; he really wasn’t the zealot waiting for heaven like his grandmother he’d believed he was.

He’s since claimed that being an adolescent and so secluded it became very difficult to think about anything but lust. By the end of his six-year stint as a monk, he was worn out by sexual urges so a priest advised him to rejoin the big, wide, secular world. But, inevitably, what came next was a huge shock to his system… he jumped straight into the the British Army, specifically the Royal Army Medical Corps, for he could no longer avoid doing his National Service. By his own admission, he was an incompetent soldier, apparently getting through the experience by taking on the role of the unit clown, crying when shouted out on parade, during which he sometimes wore red leather slippers. His final job as a squaddie was to look after the CO’s pig.

Yet, it wasn’t all bad. In 1992 he admitted to a UK newspaper that it was during his two years in the Army he “discovered sex, started practising it in a frenzy and rejected the Church very swiftly”. This, however, did leave him “with a huge residue of guilt. Sometimes God knocks on the side of my head now and says: ‘Let’s get back together’. But I prefer guilt, lust, anxiety, lies, and confusion. I prefer the uncertainties of life”.

It was around this time that he concluded an actor’s life may be for him, but after being accepted on a drama course (at the Rose Bruford College of Speech and Drama in Sidcup, Kent) he had to wait seven months before it started, so for a brief time took to the sea in the Merchant Navy. This seemed – strangely perhaps, given his general experience in the Army – to suit him admirably. He’s described the experience as genuinely ‘bohemian’ – not least because there were yet more girls to distract him in ports around the world, of course.

At drama school, he eventually met the first girl that truly stuck – her name was Anna Wheatcroft, they fell in love and were soon married. And, despite having two sons together, David and Piers, the marriage and Tom’s life quickly turned into a disaster. Owners of a successful rose-growers’ business, Anna’s parents never allowed Tom to forget that he had come from nothing, unlike their daughter.

.

.

And according to his autobiography Who On Earth Is Tom Baker? (1998), their control over his and Anna’s lives eventually led to him nursing her father when he became desperately ill. Sending Tom into a spiralling depression, the experience saw him down a clutch of his father-in-law’s anti-depressant tablets in a suicide attempt; however, it was the father-in-law that died, not Tom. The latter, in fact, ended up working in the Wheatcrofts’ rose fields along with orderlies, allowing his mother-in-law the opportunity to mock him openly. Eventually, Baker snapped and, following an incident in which he threw several hoes at the woman, left his wife and their kids for Birmingham. And never went back, not least because Anna quickly found someone else.

His marriage may have disentegrated, but Baker didn’t give up. By 1965 he was in London and hired by Laurence Olivier as a member of his National Theatre. Acting-wise, there’s no doubt this was the making of him and in subsequent interviews he’s suggested it was a time of huge professional and artistic satisfaction, despite him never getting close to becoming famous as a member of the company, nor making any real money.

Yet, after a few years, he finally hit the big time. Or so it seemed. Suggested for the role by Olivier himself, Baker was cast as Rasputin, the (yes) monk whom enjoyed a much scrutinised, intensely powerful position within the court of Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra, the last, tragic royal rulers of Russia before it was consumed by Bolshevism in 1917. The producer was Sam Spiegel, the film was the multi-Oscar-nominated Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) and for his performance Baker received no less than a Golden Globe award nomination.

Making hay as the sun shined, our man Tom followed this by playing the Wife of Bath’s young husband in Pier Pablo Passolini’s well received adaptation of The Canterbury Tales (1972), then gave a charismatic villainous turn as chief baddie Koura in Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion blockbuster The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad (1973) and in the same year delivered a similarly memorable performance in the Hammer horror anthology flick The Vault Of Horror as Moore, the boho artist whom discovers the subjects he paints all quickly snuff it, until the curse is broken when it’s revealed he once half-finished a self-portrait, leading to his own grisly demise.

But – although thanks to these fine supporting roles in distinguished movies that made full use of his pseudo-crazy charisma, boggling eyes and huge grin, Baker looked to be on the verge of genuine cinematic stardom – the truth was sadly and dramatically anything but. As was also revealed in the aforementioned Films Illustrated article, at the point of Sinbad‘s release, he was living in a tiny, single room apartment in The Smoke with barely any possessions, making ends meet as a labourer because he still couldn’t scrape together enough money as an actor. Even though he’d been a Golden Globe nominee just a year before and was receiving constant goodwill from the theatre in-crowd and the press.

He explained in the article: “In between talking to you and whatever else Columbia want me to do to promote The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, I suppose next week I will be working for the Cadogan Employment Agency, which means I shall be putting emulsion on people’s walls or scrubbing the front steps”. Years later, he also claimed of similar building-site-work around this time: “[It] was so hard that it soothed me. Being shattered at the end of each day helped me get through the night. As it sank into my poor nut that sheer bone-shaking activity was good for me, I redoubled my efforts and always asked to take the Kango drill”.

.

Self-portraiture, sorcerer and Sherlock: in The Vault Of Horror (l) and The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (m) and as Holmes (to Terence Rigby’s Watson) in The Hound Of The Baskervilles (r)

And then it happened – ironically at the point in his life where he was in perhaps the greatest grip of austerity and (who knows, surely for anyone else) despair he was was doomed to a life of menial work. Out of desperation, he wrote a letter to someone he knew in the BBC’s drama and serials department saying he was available for anything. Two nights later he got a call from drama producer Barry Letts asking to attend an audition the following morning. Baker went along, did his thing and, to his huge surprise and no doubt great delight, landed the gig as Jon Pertwee’s successor in the already hugely popular Doctor Who. Apparently, Letts wasn’t merely impressed by Baker’s audition, he’d also seen something in his performance as Sinbad‘s villain.

Suddenly, like being caught in the solar winds cast out by some malevolent sun in a Who script, his life was turned upside down. Quite simply, following his appearance alongside Elisabeth Sladen (then companion Sarah Jane Smith) at his press announcement as the new Doctor, for which he was curiously dressed in a slightly tatty looking combo of white suit, patterned jumper and tie (he genuinely possessed few other clothes at this point; see image above), he would within months become a household name. That was simply the power of Doctor Who and the result of him at 40 years-old fortuitously, deservedly and finally landing very much on his thesping feet.

For, while during Baker’s first season, Letts and script editor Terrance Dicks handed over the show’s reins to the up-and-coming Philip Hinchcliffe and his seasoned script editor Robert Holmes, the actor made the role absolutely his own. His Aristide Bruant-inspired outfit and off-centre charisma (with those boggly eyes and goofy grin, of course) perfectly emphasised The Doctor’s fey, genius alienness, while his National Theatre-honed acting chops ensured he delivered perfectly the sombre and weighty dialogues, monologues and moments of dark drama (of which there were many in the gothic horror-infused Hinchcliffe/ Holmes era). In short, he was the perfect Doctor for the times – probably for all times.

His own verdict on his performance is truly amusing in a surprisingly-frank-rather-than-self-deprecating-way: “All that was required was an ability to speak gobbledegook with conviction, which I found easy because all my life, including the years in the monastery, I had been taught nonsense by priests and teachers, on all sorts of subjects”.

The show then, as mentioned, already on a high thanks to the highly popular Pertwee years, went stratospheric. If Gerry Anderson’s Thunderbirds (1965-66) created a mid-’60s children’s TV phenomenon, then Baker’s Who years undoubtedly delivered the ’70s equivalent. It and his mug were everywhere – in spin-off books, annuals, comics; on other TV shows (Blue Peter most often, as well as The Multicoloured Swap Shop – see video clip above), lunchboxes and, yes, er, mugs.

Baker too never missed an opportunity to promote the show – spending a proportion of his down-time from filming travelling up and down the country, visiting the provinces and meeting his adoring fans of all ages, shapes and sizes. This is true to such an admirable extent that in ’78 – at the height of ‘The Troubles’, lest we forget – he popped over to Northern Ireland to visit schools – both Catholic and Protestant (see video clip below). In the guise of Baker, The Doctor truly did cross all boundaries – and barricades.

.

.

Indeed, so popular was he that the role also brought him attention of, well, a different kind, as he also recounted in his autobiography. “One young university don persuaded me to show her my Doctor Who costume – and put it on herself,” he wrote. “She looked terrific as she threw herself wantonly on the wide Holiday Inn bed and growled: ‘Come on Doctor, let’s travel through space.’

“She really did say that. I nearly laughed in her face. But then, we were not in our right minds at the time and we had been drinking champagne. I managed to travel as far as the bed. As we grappled like demented stoats, her wearing my gear, I kept thinking I was making love to myself. At least she didn’t want to whip me, as some Who groupies did.”

After living with and often cheating on TV make-up designer Marianne Ford for much of his time on the show, he eventually fell in love once more – with, yes honestly, the actress playing The Doc’s latest companion. Tom met the lovely Lalla Ward when she was cast in ’79 as the second guise of Time Lady and fellow TARDIS incumbent Romana (following the character’s originator Mary Tamm departing after a single season).

Anyone who wants to know why he fell for Ward need only watch the outstandingly witty serials City Of Death or Destiny Of The Daleks (both 1979); Lalla is basically – and always has been and always will be – delightful. Yet, by now, the quiet, truly monogamous life didn’t suit the somewhat trumped up Tom; he was always out in Soho drinking with friends rather than spending time with his second wife. They were wed in late ’80, but their marriage ended, amicably at least, just 16 months later. Baker was a bachelor once more.

But, in fact, the dissolution of their relationship was foreshadowed by the end of the other major relationship in his life – the one he had with Who. Yes, on March 21 1981, after seven years, 41 serials and 186 individual episodes, Tom Baker’s final bow as The Doctor was broadcast in the last part of Logopolis, at the end of which he regenerated into the blonder, younger Peter Davison – the sort of star for Who new show-runner John Nathan-Turner envisaged for the synth-backed, gaudy ’80s.

Like his parting from Lalla, Tom seemed to take his parting from the TARDIS with good grace, recognising that the show needed – and thrived on – change and him hanging around longer probably wouldn’t do it any good (whether it really did that good without him in the ’80s is open to question, to be fair, but there you go). But the spontaneous, bombastic, unpredictable Baker was always ready for new acting challenges – his past experiences of the slippery slope of thesping and fame before Who being testament to that – and, him now nearing 50, it was just as true as ever.

.

Narnia, Channel Five and CGI: as Puddlegum in The Silver Chair (l), in Fort Boyard (m) and as the voice of the villainous Zeebad in the big-screen adaptation of The Magic Roundabout (r)

He went on to essay that other great fictional hero from the past (if not also from the future) Sherlock Holmes in a Sunday evening, prime-time BBC adaptation of The Hound Of The Baskervilles (1982). Produced by old colleague Barry Letts, it co-starred the well respected Terrence Rigby as Watson – it was referred to by its crew as ‘The Tom and Terry Show’. While Rigby’s Watson’s a little stodgy, Baker often impresses as Holmes, even if the series itself wasn’t greatly received at the time (see the first episode for yourself here).

Later, he co-starred in the memorably racy BBC drama serial The Life And Loves Of A She-Devil (1986), played deranged seafarer Captain Redbeard Rum (whom possessed ‘a beard you could lose a badger in’) in the Blackadder II episode Potato (1986); appeared as Puddlegum in The Silver Chair (1989), itself part of the Beeb’s acclaimed adaptation of CS Lewis’s Narnia novels; portrayed Professor Plum for the ’92 series of ITV’s Cluedo gameshow (1990-93) and essayed a veteran surgeon in the same channel’s medical drama, er, Medics (1990-95). Along the way, he also featured with Eric Morecambe and ’70s Bond Girl Madeline Smith in the comedy short The Passionate Pilgrim (1984), which inexplicably was shown on the same UK cinema bills as the Bond film Octopussy and computer-themed teen flick WarGames (both 1983).

As the ’80s progressed, Baker’s Soho-based bachelor lifestyle began to lose its oomph and he reignited a love affair with TV executive Sue Jerrard (which had ended when he’d met Ward). They moved into a converted school in Kent in ’86 and married the following year. He and Sue are still married and after living in France for a brief time, moved back to Blighty in 2006 – surrounded as they’ve always been by cats and blessed with a large garden in which Tom’s able to indulge his soothing interest in horticulture.

Gone now, of course, are the days when he was a prime-time TV actor; these days many of his professional endeavours seem to be narratives and voice-overs for everything from adverts to videogames and Doctor Who audio adventures to attractions at The London Dungeon and Alton Towers. Yet, since the turn of the millennium, he’s popped up as a terrific panelist and guest host of Have I Got News For You (1990-present) and in supporting roles in Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer’s BBC revival of Randall & Hopkirk (Deceased) (2000-01), Channel 5 gameshow Fort Boyard (2003), the Beeb’s Scottish Highlands-set drama Monarch Of The Glen (2004-05), a computer-animated movie version of The Magic Roundabout (2005) and, of course, as the narrator of the BBC sketch-show Little Britain (2003-06) and its US effort (2008).

Moreover, after maintaining a prickly relationship with Doctor Who ever since he left the show (as its directly preceding and most popular star, he refused to appear as The Fourth Doc in 1983’s Davison-era 20th-anniversary story The Five Doctors, so while all three other previous Docs properly appeared, he only featured in previously shot footage), in recent years his stance has softened and he’s become a regular on the geek-out Who convention and appearances circuit – even alongside other actors to have played the Time Lord. Indeed, his beloved status as ‘The Doctor’ – as well as his barmily, brilliantly witty demeanour – was never better captured than when huge fan and impersonator Jon Culshaw stunt-called Baker for the original BBC Radio 4 run of comedy hit Dead Ringers (2000-07) – do listen to it below by playing the bottom video clip, it’s honestly hilarious.

So to sum up, who is – what is – Tom Baker? Yes, he was The Doctor, The Doctor, but as I hope I’ve maybe suggested to you dear reader in this somewhat indulgent blog post, so much more besides. His life has genuinely been a fascinating, logic-defying, unconventional ride of highs and lows like a light-speed journey in the TARDIS through a heavy turbulence-inducing meteor shower. In the end, though, he’s an unmitigated, unmistakable legend; after all, who else in the mid-’70s would, while travelling in a car back from a Who event one Saturday evening, stop off at a random house in Preston to check out the latest episode of the show because he wanted to see how it played on-screen, flabbergasting and delighting the home’s family in equal measure, especially the kids? His take on this escapade? “Those were the days. I was a hero in Preston and far around the world. And now what? Now I get mistaken for Shirley Williams…”

.

Further reading:

See George’s Journal‘s pictorial celebration of Doctor Who in the 1970s here

Read George’s Journal‘s review of The Ark In Space (1974) here

Read George’s Journal‘s review of Genesis Of The Daleks (1974) here

Read George’s Journal‘s review of Pyramids Of Mars (1975) here

Read George’s Journal‘s take on why Doctor Who is one of the 1970s’ ultimate TV shows here

Read George’s Journal‘s article on The Doctor’s regenerations (including Pertwee into Baker and Baker into Davison) here

.

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Tomb raiders: The Fourth Doctor and classic companion Sarah Jane Smith’s Edwardian brush with ancient Egyptian iconography soon becomes an encounter with an all-powerful alien

I don’t know, just like last year was for James Bond, this oh-so celebratory 50th annus for The Doctor is truly proving as eventful as it is commemorative. A half-season of new stories that’s split opinion, an upcoming autumn special featuring three Docs as well as a Christmas episode, plus numerous other events… and now, and now, we’ve just been introduced to the – imminent – next incarnation of the Time Lord, Peter Capaldi, no less.

And all that’s not even to mention this very blog‘s dedication to all things Who Doctor is also on-going in celebration of his golden anniversary – indeed, this latest post (itself the latest in a series of reviews of notable Doctor Who stories) focuses on a belting serial of the show’s past that Mr Capaldi would surely have given his soon-to-be-deployed sonic screwdriver to have starred in.

Yes, with its smart sci-fi spin on pre-WWI Egyptian archaeological adventuring, Pyramids Of Mars is undoubtedly one of my absolute favourites of the show’s back-catalogue, but just (‘doctor’ who, when, what, how) and why? Well, read on, dear reader…

.

.

.

Doctor: Tom Baker (The Fourth Doctor)

Companion: Elisabeth Sladen (Sarah Jane Smith)

Villains: Gabriel Woolf (Sutekh); Bernard Archard (Marcus Scarman); Peter Mayock (Namin); Nick Burnell, Melvyn Bedford and Kevin Selway (Mummies)

Ally: Michael Sheard (Laurence Scarman)

Writers: Robert Holmes and Lewis Greifer (under the pesudonym ‘Stephen Harris’)

Producer: Philip Hinchcliffe

Director: Paddy Russell

.

.

.

.

.

Season: 13 (third of six serials – comprising four 25-minute-long episodes)

Original broadcast dates: October 25-November 15 1975 (weekly)

Total average viewers: 10.3 million

Previous serial: Planet Of Evil

Next serial: The Android Invasion

.

.

.

.

.

The Fourth Doctor, his erstwhile companion Sarah Jane Smith at his heels, departs his TARDIS (the flight-path of the trusty blue police phone box-cum-relative-dimension-defying time-and-space machine having been tampered with) to discover he’s standing in front of a priory that in several deacdes’ time will be Brigadier Sir Alistair Lethbridge-Stewart‘s Southern-England UNIT HQ. At present, it’s the ancestral home of Edwardian archaeologist Professor Marcus Scarman. The latter is nowhere to be found on the grounds, though (little do our protagonists know, at the exact second the TARDIS was interfered with, Scarman had been attacked by a superior being in an Egyptian pyramid).

In Scarman’s place, the Egyptian-artefact-teeming priory is under the command of the eerily mysterious Ibrahim Namin, whom is far from popular with the butler. Heeding the latter’s warning, the duo escape a gun-toting Namin and a clutch of white rag-encased mummies he appears to have summoned. They make their way to a hunting lodge in the woods, which they discover is the home of Laurence Scarman, Marcus’s brother, an amateur scientist. Laurence’s latest invention is a ‘Marconiscope’ – a device The Doc instantly recognises as a primitive radio telescope and with which he intercepts a message from Mars: ‘Beware Sutekh’.

Beginning to piece things together, our hero informs the others that Sutekh (also known as ‘The Destoyer’) is a member of the mighty Osirian alien race, whom it’s known, led by the latter’s brother Horus, in the distant past defeated the pan-genocidal, megalomaniac rebel Sutekh on Earth – thus establishing the line of Ancient Egyptian gods. Meanwhile, with his mummies in tow, Namin welcomes the black-clad ‘Servant of Sutekh’, whom arrives in the priory through a portal, or literally a space-time tunnel – and then instantly kills the human, as Sutekh no longer requires another servant (see video clip above).

As the hiding Doctor, Sarah and Scarman look on, the ‘Servant’ reveals himself to be the latter’s brother Marcus, utterly under the telepathic control of the near-omnipotent Sutekh. Near-omnipotent, that is, for he’s still trapped in the tomb that Marcus Scarman stumbled upon, held there The Doc also works out (thanks to the message from the ‘Marconiscope’) by some great force or signal from Mars set up by the long since dead Osirians, but still very much working. Sutekh, therefore, aims to use the unfortunate Marcus Scarman and his mummies (soon revealed to be embalmed robots) as practical tools to build an Osirian ‘war missile’ – a large white pyramid – in the priory’s grounds that can be launched to Mars and destroy the signal so he might free himself from its lasting-for-eternity-intended grip and destroy the universe, as is his wont.

The Doc comes up with three different ideas of how he might prevent Sutekh controlling his minions, each of which prove fruitless. First, once Marcus Scarman has moved away, he attempts to dangle his TARDIS key into the space-time tunnel (between the priory’s hall and the Sutekh’s pyramid tomb) through which Scarman has just travelled and through which he communicates directly with Sutekh; however, Osirian power so overwhelms The Doctor as he does so, he’s knocked-out. Second, he collects the ring from the finger of the dead Namin, realising that it – transmitting a direct signal from Sutekh – was what was controlling the mummies. And, third, he tries to jam Sutekh’s overall control by modifying Laurence’s ‘Marconiscope’; yet, at the critical moment when he’s finished his work on the apparatus and it should start working, Laurence – in distress that his puppet-ified brother will be killed once Sutekh’s power over him is relinquished – sabotages it.

The Doctor: Mr Scarman, I really must congratulate you for inventing the radio telescope 40 years early

Laurence Scarman: That, sir, is a ‘Marconiscope’. It’s purpose is…

The Doctor: … is to receive radio emissions from the stars

Laurence Scarman: How could you possibly know that?

The Doctor: Well, you see, Mr Scarman, I have the advantage of being slightly ahead of you. Sometimes behind you, but normally ahead of you

Laurence Scarman: I see…

The Doctor: I’m sure you don’t but it’s very nice of you to try

Foiled in his efforts, The Doc then decides they must simply destroy the partly constructed war missile – and an overwrought Laurence suggests using some gelignite explosive that’s to hand. The two time-travellers having departed, Marcus Scarman now investigates his brother’s lodge and despite the latter’s appeals to remember their childhood together, Sutekh’s pull is simply too strong – Marcus Scarman kills his forsaken sibling.

Meanwhile, dressed in the bindings of a captured and deactivated mummy, The Doctor successfully hides the gelignite in the pyramid-missile while Sarah fires at it with Laurence’s rifle to set it off. Her aim is true, but Sutekh telepathically suppresses the explosive’s combustion, forcing The Doc to conclude he must travel through the space-time tunnel and confront the almighty Osirian, in doing so distracting him so the combustion will resume and the missile destroyed.