![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Five minus one: “Hey look, it’s Tom Baker’s waxwork again – how the hell did it get up there…?”

So, as we’re now less than 50 days away from Doctor Who‘s (1963-present) 50th anniversary-celebrating special The Day Of The Doctor, why not take a look back at the last (proper) ‘multi-Doctor’ episode cooked up to mark a milestone in the show’s history? Why not, indeed? Here it is then, peeps, the latest post in George’s Journal‘s wee, little celebration of Who‘s golden anniversary – a close-up/ review of The Five Doctors, the November ’83 special that brought together the First, Second, Third, Fourth and Fifth Doctors. Oh, and Pudsey Bear. Yes, that’s right, Pudsey Bear…

.

.

.

Doctors: Peter Davison (The Fifth Doctor); Jon Pertwee (The Third Doctor); Patrick Troughton (The Second Doctor); Richard Hurndall (The First Doctor); Tom Baker (The Fourth Doctor)

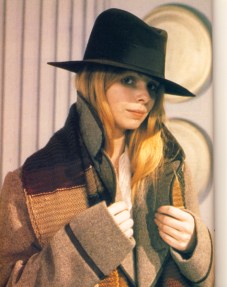

Companions: Janet Fielding (Tegan Jovanka); Elisabeth Sladen (Sarah Jane Smith); Carole Ann Ford (Susan Foreman); Nicholas Courtney (Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart); Mark Strickson (Vislor Turlough); Lalla Ward (Romana II)

Villains/ Monsters: Philip Latham (Lord President Borusa); Anthony Ainley (The Master); John Scott Martin (Dalek – voice: Roy Skelton); David Banks, Mark Hardy and William Kenton (Cybermen); Raston Robot (Keith Hodiak)

Ally: Dinah Sheridan (Chancellor Flavia)

Writer: Terrance Dicks

Script editor: Eric Sawad

Producer: John Nathan-Turner

Directors: Peter Moffatt and (uncredited) John Nathan-Turner

.

.

.

.

.

Season: 90-minute-long special (between the 20th and 21st seasons)

Original broadcast dates: November 23 1983 (US)/ November 25 1983 (UK)

Total viewers: 7.7 million (UK)

Preceding serial: The King’s Demons (Season 20)

Next serial: Warriors Of The Deep (Season 21)

.

.

.

.

.

Enjoying a rare, peaceful sojourn on the Eye of Orion (known the universe-wide as one of its most tranquil spots; although, must be said, it looks a great deal like the British countryside), the youthful, fair-haired and beige-cricket-themed-outfit-sporting fifth incarnation of The Doctor is suddenly struck by one of the most devastatingly debilitating afflictions he’s ever experienced – he can feel all four of his former selves being snatched out of their own natural times; the sensation seems to be like they’re being removed from time altogether. Worried, his present companions, Australian air stewardess Tegan Jovanka and previously duplicitous alien-cum-public-schollboy Vislor Turlough, are powerless to help him so carry the prone Time Lord back to his TARDIS, tending to him as he lies stricken on the console room floor.

Meanwhile, we witness his four other other selves indeed being scooped up by a menacing floating triangular whirlwind and out of the times and places they happen to be occupying. The First Doctor is taken from a rose garden; a giant, furry coat-wearing Second from the grounds of UNIT’s HQ with a 1980s’ Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart, whom the former’s visiting on his retirement from UNIT; the Third while driving along in his beloved pseudo-vintage sportscar Bessie; and the Fourth and companion Romana as he punts her along in a boat on the River Cam beside a Cambridge college. The first three – as well as the Fifth and his companions in his TARDIS, but not the Fourth and Romana, whom get stuck in the Time Vortex – end up on the barren, foreboding landscape of an unknown planet – none of them aware the others are also there. But who has snatched them and plonked them down there? And why?

Whomever it is and their purpose, it has the Inner Council of the Time Lords worried. And as they discuss the fact the Doctors’ displacements from their correct times is draining the all-important Eye of Harmony (the source of the Time Lords’ time- and space-travel energy, which is located at the heart of the Capitol of their planet Gallifrey), we learn that it’s actually down on the surface of Gallifrey that the Doctors have all been placed. Not just there, though, specifically-speaking, they’re all in the über-hostile ‘The Death Zone’ – a fatally dangerous environment that surrounds the Dark Tower, the tomb of the founder of Time Lord society, the great Rassilon. The Death Zone was apparently created way back in the ‘Dark Time’ by the Time Lords’ ancestors, whom cruelly devised it for their own sport – they would time-scoop aliens from different times and spaces and put them in The Death Zone to fight it out to the death. Nice.

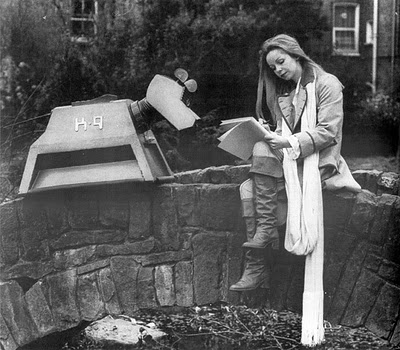

As the Second Doc gets his bearings and passes on the bad news to the Brig, they’re suddenly chased by a squad of the ultimate cyborg killers, the Cybermen (also moved to The Death Zone it seems). For his part, the First Doctor finds he’s in a hall of mirrors and runs into Susan Foreman, his very first companion and, in fact, his grand-daughter (presumably she’s been time-scooped too), and quickly the pair have to escape from a, yes, time-scooped Dalek. Meanwhile, the Third Doctor – still driving along in Bessie – spies a young woman needing help after falling down a steep hill-face. Rescuing her, he immediately recognises her and she him, for the woman is Sarah Jane Smith, his and the Fourth Doctor’s journalist companion, whom we witnessed time-scooped herself from outside her London home just after being warned of danger by super robotic dog K-9 (she’d received him as a gift from The Doc in 1981’s one-off, Doctor-less Christmas special K-9 And Company).

The Inner Council – made up of Lord President Borusa, Chancellor Flavia and security chief the Castellan – now welcome into their midst the man who’s their very dodgy roll of the dice to aid the Docs’ escape from The Death Zone and put a stop to the Eye of Harmony’s drainage… The Master, The Doctor’s nemesis – the skunk to his mongoose. They suggest to him his sly, devious yet brilliant mind may just be the tonic for the Docs, if he can be trusted; they successfully bribe him into taking on the mission by promising a pardon for all his past crimes and a new cycle of regenerations (him having used up all his previous ones). Accepting, he is furnished with a transmat-recall device and is sent into The Death Zone.

Tegan: Doctor, what is it?

The Fifth Doctor: It’s fading. It’s all fading…

Turlough: What’s fading?

The Fifth Doctor: Great chunks of my past, detaching themselves like melting icebergs

His mission gets off to a sticky start, however, as when he comes across the Third Doctor and Sarah they instantly dismiss his claims he’s there to help and move on – so he then seems to seek an alliance with the squad of Cybermen. Meanwhile, the First Doc and Susan spy on the horizon the Fifth’s TARDIS and set off for it. Gaining entry into the machine (because, well, effectively it’s his), the First meets his Fifth incarnation and, learning the TARDIS can get no nearer to the Dark Tower owing to a forcefield, grudgingly agrees to form an alliance with the Fifth to gain entry to the tower – like both the Second and the Third, the two Docs have deduced the key to returning to their correct times must lie in the tower. Owing to the First’s elderly state, the Fifth suggests the former ought to remain behind in the TARDIS while he seeks a way into the tower; he’s accompanied by both Tegan and Susan. However, quickly the trio are surrounded by Cybermen – with their new ‘ally’ The Master in their wake. The latter, however, hasn’t allied himself with the Cybermen at all and is knocked out by a cybergun blast, dropping as he falls to the ground his transmat-recall, which the Fifth picks up, recognises and depresses to escape.

Materialising before the Inner Circle in the Capitol, the Fifth Doc realises he’s misjudged The Master and figures that the Cybermen found them both too easily – it’s as if someone was controlling or communicating with them. He examines The Master’s transmat-recall and discovers it contains a homer (which had presumably attracted the Cybermen to them both). It’s revealed that the Castelan had supplied The Master the transmat device, thus he is arrested; the assumption being he placed in it a homer and is the Inner Circle insider manipulating events. Furthermore, items that apparently contain secrets from the Dark Times are found in a search of his quarters, seemingly incriminating him beyond doubt. As he’s taken away to be interrogated via ‘the mind probe’, The Doctor, Borusa and Flavia hear a shot and a cry – a guard claims the Castellan was shot trying to escape, but the Doc has grave doubts about what’s going on…

Outside in The Death Zone, the Third Doctor and Sarah manage to gain entrance into the tower having got past ‘the most perfect killing machine ever devised’ the Raston Robot, when the latter attacks and one-by-one easily eliminates a number of Cybermen. The Second and the Brig too get inside after, journeying through subterranean caves, they escape the clutches of an alien-devised robotic Yeti monster (the like of which the’d previously encountered together on Earth). Furthermore, on Tegan and Susan’s return to the TARDIS to inform the First Doctor of the Fifth’s plight, The First decides he must venture out himself, with Tegan in tow, and the pair eventually reach and enter the tower – through the front door, in fact, which seems far too straightforward.

Indeed, it is. Inside they meet the cunning Master, whom points out all they have to do venture into the tower proper is to cross a grid that resembles a chess board. The grid is booby-trapped, however, which the now arrived remainder of the Cyber squad is not aware of. Luring them across, The Master leads them to obliteration-by-laser. Yet, latching on to a cryptic clue made by The Master, the smarter-than-the-average-Time-Lord Doc quickly deduces that to cross the grid safely one must make calculations involving the mathematical Pi equation. Therefore, he and Tegan safely make it across the grid after the now disappeared Master.

On their way through the tower, the Second and Third Doctors too face obstacles; this time in the guise of previous companions: Scots Highland soldier Jamie McCrimmon and 21st-Century scientsist Zoe Heriot (for the Second) and UNIT alumni Dr Liz Shaw and Captain Mike Yates (for The Third). Soon enough, though, both Docs realises these are just spectres conjured up by the will of the long-since-departed Rassilon to – like the grid – prevent intruders gaining entry to his tomb. Denying their respective companion-spectres then, both Docs and their real companions are able to continue and, like the First Doc and Tegan, eventually find their way into the tomb, at which point everyone becomes (re)acquainted.

The Fifth Doctor: I’m certainly not the man I was. Thank goodness!

Having deciphered from ‘Old High Gallifreyan’ an inscription, the three Doctors find out that, before his death, the all-powerful Rassilon had discovered the secret to immortality and was apparently prepared to share it with any Time Lord whom might overcome the obstacles in the Dark Tower and gain entry to his tomb (see video clip above). Just then – and right on cue – The Master reappears and announces he’s arrived to claim said immortality (something he’s ventured to Gallifrey for before now); amusingly defeated by a spot of human brute force, he’s knocked out by the Brig and tied up by Sarah and Tegan. Manipulating controls in the tomb, the Docs now disable the forcefield preventing the TARDIS entry to the tower, allowing Susan and Turlough to pilot it into the tomb and join the others.

Meanwhile, left alone in the Inner Council’s chamber, the Fifth Doc’s attempts to discover who’s behind everything hit a breakthrough when he realises Borusa has disappeared, discovers the chamber’s transmat machine is disabled and is informed nobody’s got past the guards and so departed the Capitol. The Lord President must have left the chamber via some sort of secret door then. Eventually, the Doc works out a code that might open such a door and low and behold a concealed door opens – into a darkened room where he finds… Lord President Borusa. Using a Rassilon-related item of great power, the latter overpowers the Doc and forces him to obey his commands, informing him that, like the other three Doctors, he too had discovered Rassilon’s harnessing of immortality and grew to desire it so he might rule Gallifrey forever not just until he dies a natural death at the end of his regeneration cycle. Thus, he’d conceived a plan to bring all the Doctors to The Death Zone to gain entry to Rassilon’s tomb in order to get past the obstacles and make it far easier for him to gain entry by merely following them.

Thus, easily transmatting himself and the Fifth Doc to the tomb, Borusa now – via the controlled will of the Fifth – attempts to control the minds of the other three Doctors as well. This he accomplishes, but by combining their will, the latter trio and the Fifth manage to break his grip on them. Now, though, the voice of Rassilon booms around the tomb demanding to know whom wishes to gain immortality. Borusa takes his cue and claims he does; together, the Doctors step forward to try to prevent the inevitable, but the First holds them back. Borusa takes the ring from the finger of the prone body of Rassilon, only to be frozen still and his body transferred on to the side of the latter’s sepulchre – he has immortality, but it’s a living death for him and, like we see next to him, other Time Lords whom over the eons have successfully sought the same.

As Rassilon frees the Fourth Doctor and Romana from the Time Vortex and returns them to their correct time and space, he also sends away The Master (‘his sins will find their punishment in due time’). Smugly, the First Doc explains to the others that another part of the inscription they’d deciphered said ‘to lose is to win and he who wins shall lose’. From this he’d thus deduced that taking Borusa’s offer of immortality was an ingenious trap left by the great Time Lord to wheedle out and remove far too ambitious, nay evil, future descendants, so all that had been needed was for Borusa to seal his own fate.

Upon saying their farewells and – in the Doctors’ cases – insulting each other one last time, group-by-group the time-travellers step into the TARDIS and, via the latter separating into multiple TARDISes, return to their respective times and spaces, leaving only the Fifth Doc, Tegan and Turlough behind. After all they’ve been through, however, there’s another hurdle to jump – Chancellor Flavia appears on the scene with guards, claiming The Doctor must now take control as the rightful Lord Chancellor (him having assumed the position in a previous time of crisis and Borusa having essentially only inherited it on the Doc’s last departure from Gallifrey). Anxiously, The Doctor whispers to his companions to scarper into the TARDIS and, claiming he’ll follow Flavia back to the Capitol in the machine, he does likewise. Once inside, he explains to his bemused friends that he (and in turn they) are now on the run from Gallifrey – in fact, just as he always has been since the very beginning…

.

.

.

.

Fair dues, The Five Doctors is a pretty long way short of being the best Who serial/ episode ever made, yet for the simple reason it’s (so far) the ultimate ‘multi-Doctor’ story, it is unquestionably an essential serial/ episode in Who history. Intentionally produced and broadcast as a standalone special to mark the show’s 20th anniversary, it followed 10 years – and a few months – on the heels of the first decade-marking The Three Doctors (1973) special, which boasted then current Doc Jon Pertwee and the two previous incarnations of the character, William Hartnell and Patrick Troughton (although the former of those two didn’t actually appear on-screen in it with the other two, owing to poor health; sadly he’d die just two years later).

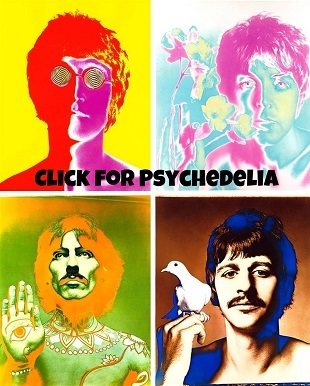

Yet, while The Three Doctors was certainly well received in its time (it also introduced splendid Time Lord villain Omega, after all), The Five Doctors would fundamentally trump it in two significant areas. First up, in spite of it not ‘properly’ featuring Tom Baker as The Fourth Doctor (see reasons below) and the obvious lack of Hartnell, it nonetheless offered its only-too-eager early ’80s Who-dience a quintet of Docs – Davison’s then current Fifth, Pertwee’s Third, Troughton’s Second, Baker’s Fourth (sort of then) and filling in as the First, an excellent impersonation from seasoned thesp William Hurndall. Moreover, aside from Baker’s, all four of them appear on-screen together.

The other area where it stands head and shoulders above its anniversary-celebrating predecessor special is in just how many companions it features. Understandably, the Fifth Doc’s entourage of the time, Janet Fielding’s Tegan ‘The Mouth on Legs’ Jovanka and Mark Strickson’s Turlough feature prominently (although both are far from great), but we’re spoilt with reappearances from Elisabeth Sladen‘s rightly adored Sarah Jane, Nicholas Courtney’s ever popular Brig and, surely best and most surprising of all, Carole Ann Ford’s Susan, The Doc’s grandaughter and his very first companion. There’s even cameos from Troughton era associates Frazer Hines’ Jamie and Wendy Padbury’s Zoe (not seen since their sad farewell in 1969’s The War Games), Richard Franklin’s Mike Yates and Caroline John’s Liz Shaw from the Pertwee era (the latter not seen since 1970’s Inferno) and we also get the briefest of moments from Baker-era companion Lalla Ward‘s Romana II and that Doc’s faithful friend K-9. Plus, lest we forget, there’s Anthony Ainley’s then current version of The Master too – this time, though, intriguingly taking on a would-be Iago role instead of out-and-out villain duties.

All the same, The Five Doctors does have its drawbacks – mostly to do with the script. On the surface, there’s little really wrong with Terrance Dicks’ writing (as Who serials/ episodes go, it’s solid enough; certainly by the time of the ’80s when the quality dipped in general), but measured against the best, the dialogue lacks spark and there’s plot problems (The Death Zone isn’t exactly original – it’s effectively a retread of the plot conceit in The War Games, which was way more compelling) and incongruities (why do the first three Docs and their companions seemingly all leave in their own TARDISes at the end when only one TARDIS – the Fifth’s – actually travelled to Gallifrey?). Mind you, the revelation of Borusa as the villain ain’t bad – while maybe predictable, it’s conceivable and interesting to witness a twice previously featured lofty, by-the-book Time Lord (1977’s The Deadly Assassin and 1983’s Arc Of Infinity) become drunk with power – and it’s nice finally to meet Rassilon (albeit his Jor-El-like, echo-from-the-past face) and the Raston Robot is a fine idea for a monster that generates some genuine tension; pity it’s not more imaginatively deployed, mind.

Overall, though, the best thing about The Five Doctors is, well, what was also best about The Three Doctors: the interaction of all the Docs themselves. As mentioned, William Hurndall does something of a remarkable job of bringing the stubborn, high-minded First Doctor back to life, while watching the Second and the Third bickering once more is a delight (the former, when they depart, insulting the latter as ‘fancy pants’ and the latter calling the former ‘scarecrow’). Plus, even Davison’s Fifth version irritates the others by proclaiming of all of them he’s ‘the most agreeable’; a sign The Doc has always thought a great deal of himself, despite however modest he likes to be – at times. Indeed, let’s not forget too, the latter’s dash away to his TARDIS at the very end, evading fulfilling his duties as Gallifrey’s rightly appointed Lord President (which references what took place in 1978’s The Invasion Of Time) and echoes ‘how it all began’ in the first place – his running away from his planet in a stolen space- and time-machine. All said then, The Five Doctors is an episode that, despite its faults, is a highly continuity-friendly and jolly, smile-inducing love letter to the show for surely every Who fan.

.

.

.

.

.

For right or wrong, The Five Doctors‘ journey to the screen was almost as torturous as that of the five Doctors themselves through The Death Zone to old Rassilon’s tomb. Then producer John Nathan-Turner had been intending a Three Doctors-style special to celebrate the show’s 20th anniversary from an early stage and planned to get the thing in place so it could be shot at the end of the 20th Season’s final filming block (which, with its focus on returning villains/ monsters from the show’s past, had already been something of a consciously celebratory season anyway).

And everything went swimmingly until script editor extraordinaire of ’70s Who Robert Holmes was brought on board to write it. To begin with, Nathan-Turner had apparently had to be coaxed into giving Holmes the job – on the advice of turning to a very safe pair of hands for such a prestigious episode’s scripting – because he was always rather intimidated when working with previous ‘big beasts’ of the show. Not that that would have mattered as it turned out, as Holmes had trouble with the script right the way along. Originally he proposed entitling the episode The Six Doctors and having The First Doctor character (and Susan) turning out to be cyborg impersonators. This being deemed far too radical and thus thrown out, his other idea was to have The Doc experience peril by regressing through his five incarnations, meaning the episode would have begun with the Fifth and reached its climax with the First. Although this would undoubtedly have been interesting, it too was vetoed, presumably on account of the fact that current Doc Davison would have been out of the story very early on. Eventually, full of frustration, Holmes decided he wasn’t getting anywhere and walked, leaving Terrance Dicks, the man he’d previously replaced as the show’s script editor, to take his place.

Mind you, it wasn’t plain sailing for Dicks either, as he was asked to come up with a hasty 11th-hour rewrite of his final draft because one of the episode’s stars had decided to u-turn on his earlier decision to appear in it. Yes, that would be Tom Baker, of course. In two minds throughout (albeit amiable) negotiations with Nathan-Turner to appear, the last Doctor but one seemingly decided that starring alongside all the other Docs – and especially his replacement – would be too raw an experience for him. Or his ego simply told him he was above it all (knowing full well he was perceived by the public as ‘The Doc of Docs’, after all).

Either way, he blinked at the last minute, thus the production team came up with the ruse of using never-before-seen footage from the ill-fated, unfinished serial Shada (1980) for his and Lalla Ward’s involvement in the episode (hence why Dicks wrote in the explanation of why they didn’t make it to Gallifrey like everyone else; in fact, Baker’s Doc had been intended to be accompanied by Elisabeth Sladen’s Sarah Jane). But this potential calamity actually proved a blessing in disguise; years later Dicks admitted he’d originally made Baker’s Fourth Doc the one whom meets the dignitaries in the Capitol and discovers Borusa’s plot, but Baker’s withdrawal saw Dicks shift this role to Davison’s Fifth Doc, a fortunate change as it ensured the then current Doctor would fittingly play the dominant role in the story.

After the palaver of its writing, the episode’s shooting proved relatively smooth. This was despite ‘actors’ director’ Peter Moffat (whose existence had years before forced Peter Davison for performer-union-purposes to adopt the ‘stage’ surname ‘Davison’ in place of his real surname – yes, ‘Moffat’) being far more comfortable with helming the drama as opposed to the action, thus ensuring Nathan-Turner eagerly stepped in to direct the Raston Robot action sequence.

Indeed, to ensure things remained smooth, Nathan-Turner had also arranged that, as much as possible, Davison, Pertwee and Troughton were kept apart during filming until they were actually shooting their shared scenes in the climax. Yet, this turned out to be over-cautious, as ego clashes were far from the agenda when they eventually worked together. So much so that during a later photo-call in which they all appeared with other guest-stars (including K-9), they seemed to enjoy themselves greatly – at the absent Tom Baker’s expense, that is. As the latter had declined to turn up for filming, but (sort of) appeared in the episode, Nathan-Turner had slyly hired the thesp’s genuinely lifelike Madame Tussaud’s waxwork to fill in for these group photos. This would actually have worked rather well, had the other Doc actors not larked about around ‘Baker’ (even carrying ‘him’ about at one point), very much drawing attention to the fact this wasn’t the real Tom. Apparently, Elisabeth Sladen was rather put out by their antics, deeming them disrespectful, but the trio clearly had great fun (for images of the event – see here).

In a first for the show, The Five Doctors was actually broadcast in the States before it was in the UK, going out, as it did, on US screens on the evening of Who‘s 20th anniversary (November 23 ’83), while UK fans had to wait two days longer to see it (no illegal streaming back then, of course). The reason for this was the old Beeb had cannily held it back to form the centrepiece of that year’s Children In Need appeal (see video clip below), necessitating then it being broadcast on the last Friday evening of November (when the highly successful telefon has traditionally always been broadcast) rather than two nights before to coincide perfectly with Who‘s anniversary. Admittedly, no ‘Whovians’ in Blighty seemed particularly miffed at this; after all if it was good enough for Pudsey, then surely it was good enough for the rest of us, Who-nuts or not.

.

.

.

Next time: The Caves Of Androzani (Season 21/ 1984)

.

Previous close-ups/ reviews:

City Of Death (Season 17/ 1979/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

The Talons Of Weng-Chiang (Season 15/ 1977/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

The Deadly Assassin (Season 14/ 1976/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

Pyramids Of Mars (Season 13/ 1975/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

Genesis Of The Daleks (Season 12/ 1975/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

The Ark In Space (Season 12/ 1975/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

The Dæmons (Season 8/ 1971/ Doctor: Jon Pertwee)

Inferno (Season 7/ 1970/ Doctor: Jon Pertwee)

The War Games (Season 6/ 1969/ Doctor: Patrick Troughton)

An Unearthly Child (Season 1/ 1963/ Doctor: William Hartnell)

.

Talent…

.

… These are the lovely ladies and gorgeous girls of eras gone by whose beauty, ability, electricity and all-round x-appeal deserve celebration and – ahem – salivation here at George’s Journal…

.

There’s two distinct similarities between Sandra Dickinson and Liza Goddard. First, at one time they were both married to fellow thesps whom became household names by playing the magnificent protagonist in Doctor Who (1963-present) and, second, they’re both terrifically talented, glorious lovelies who graced our TV screens in the ’70s and ’80s – and without a shadow of a doubt then are the more than deserving latest entries in this blog’s Talent corner…

.

Profiles

Names: Sandra Searles (stage name: Sandra Dickinson)/ Liza Goddard

Nationalities: American/ English

Professions: Actress/ Actress and TV personality

Born: October 20 1948, Washington D.C./ January 20 1950, Smethwick, West Midlands

Known for: Sandra – playing the small screen incarnation (to be followed by Zooey Deschanel‘s big screen version) of Tricia ‘Trillian’ McMillan, female protagonist in the BBC TV adaptation (1981) of Douglas Adams’ iconic satirical sci-fi radio serial The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide To The Galaxy (1978). By this time, she had already established herself in the UK (to where she had emigrated for acting training at London’s Central School of Speech of Drama) as a consummate comedy actress, often in the guise of a dumb platinum blonde with a high-pitched voice, not least in ’70s TV ads for St. Bruno tobacco and Birdseye foods. A perennial stage performer, she’s also often appeared on-screen since Hitch-Hiker’s, notably in family adventure drama The Tomorrow People (1973-79), Cover (1981), sitcoms 2point4children (1991-99) and White Van Man (2011-12) and on the big-screen courtesy of cameos in both Superman III (1983) and Supergirl (1984). In 1978 she married second husband Peter Davison, whom three years later would assume lead duties in Doctor Who. Together, they appeared in well received stage productions of plays The Owl And The Pussycat and Barefoot In The Park and in a Christmas ’83 version of pantomime Cinderella, which was overseen by Who producer John Nathan-Turner and broadcast by ITV. They divorced in 1994, but their daughter Georgia Moffet is a successful actress herself whom in 2008 also appeared in Who (fittingly as The Doc’s daughter in, er, The Doctor’s Daughter) and subsequently married ‘her Doctor’ David Tennant.

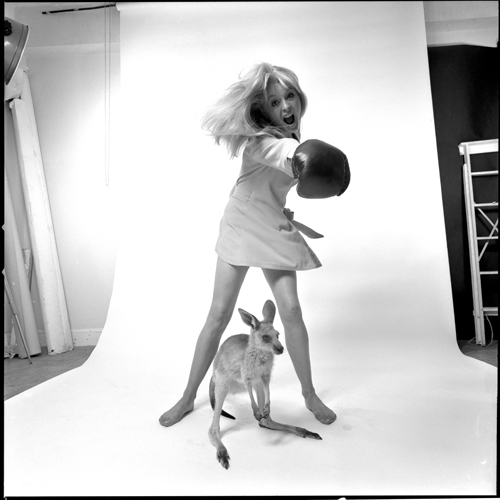

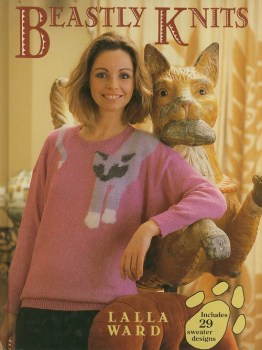

Liza – the sexiest thing to come out of the Black Country since, well, forever, Liza’s been a hugely familiar face on the British gogglebox for decades. She first made a name for herself as a tomboy teenager in the unforgettable Australian children’s drama Skippy The Bush Kangaroo (1966-68), her family having moved Down Under when she was 15. On her return to Blighty, she was quickly cast as a lead in the BBC drama Take Three Girls (1969-71) and played the same character in its sequel series Take Three Women (1982). In between, she featured in the comedy flick Ooh… You Are Awful (1972), sitcom Yes, Honestly (1976-77) and The Brothers (1972-76), a popular Sunday-night BBC drama in which she played the wife of later Doctor Who star Colin Baker, whom – life imitating art-like – she later married. In the ’80s, Liza appeared in an episode of Minder (1979-93), Hitch-Hiker’s-like children’s sci-fi quiz show The Adventure Game (1980-86), the Doctor Who episode Terminus (1983), ITV sitcom That’s Love (1988-92) and most notably as femme fatale Phillipa ‘The Ice Maiden’ Vale in Bergerac (1981-91) and as a team captain on ITV’s unforgettable panel show Give Us A Clue (1979-92). Her last prominent role came as the teacher of a child whom inexplicably transforms into a dog in the popular ITV children’s comedy drama Woof! (1989-97), produced by her now husband David Cobham.

Strange but true: Along with then husband Peter Davison, Sandra wrote and performed the theme tune to ITV’s memorable puppet show Button Moon (1980-88)/ following her divorce from Colin Baker, Liza was briefly married to ’70s glam rocker Alvin Stardust.

Peak of fitness: Sandra – in her introductory scenes from Hitch-Hikers’, (under)dressed in that appealing and revealing, bright red, low-cut leotard number/ Liza – emerging from the sea to John Nettles’ great embarrassment in the Christmas ’83 special of Bergerac (Ice Maiden) owing to her being completely in the nuddy.

.

CLICK on images for full-size

.

.

.

.

.

.

,

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

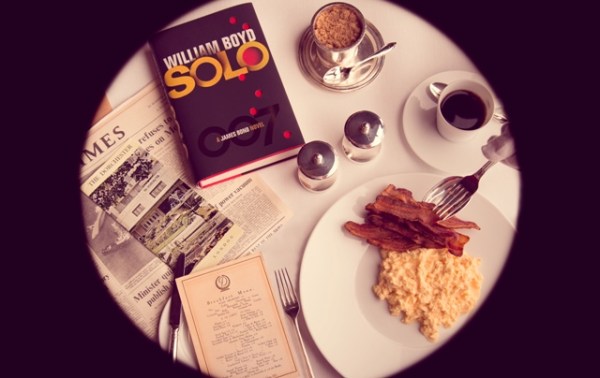

Good morning, Mr Bond: Solo’s opening chapter features Ian Fleming’s hero enjoying a fine breakfast at The Dorchester hotel – but does the novel satisfy like the perfect petit déjeuner?

.

Author: William Boyd

Year: 2013

Publisher: Jonathan Cape (Vintage Publishing/ Random House)

ISBN-9780062223128/ ISBN-10:006222312

.

Not to say that the mantle of ‘new James Bond continuation author’ is a poisoned chalice, but it’s certainly not been as snug a fit for its recent owners as that iconic shoulder holster always has been for 007. Since the publication of Devil May Care (2008) and Carte Blanche (2011), both Sebastian Faulks and Jeffrey Deaver have received their fair share of flak from Fleming die-hards for their respective novels – and noticeably neither’s received the call-back for a sequel from Ian Fleming Publications, purveyors of the literary Bond brand.

In fact, IFP have a new torchbearer, acclaimed author William Boyd, and he’s given us Solo, an adventure that sees 007 trying to end ‘a dirty little’ African civil war in the whirlwind of change that was the late 1960s. Credit where it’s due though, of this modern trio of Ian Fleming-wannabes, Boyd has definitely managed in Solo to bring readers the closest to the original Bond. Is that the best thing that can be said of Solo, though? Probably, yes; but coming after Faulks’ and Deaver’s efforts, it’s certainly not something to be scoffed at either.

Indeed, owing to his hearty stab at ‘Fleming faithfulness’, there’s much to like about Boyd’s novel. Firstly, to this reader’s mind, Boyd gets right both that Fleming-esque terse but vibrant, journalistic writing style and the Bond character. Not only is Bond replete with those wiles and that wit, that danger and that brutality, and that classiness and that stubbornness which so delight Fleming fans, but the author also builds on the 007 of the later Fleming novels by showing flashes of him starting to reflect on and accept middle-age – not only that well publicised 45th-birthday breakfast at The Dorchester in the first chapter, but also a grown-up mutual attraction with an equally confident, mature woman.

Boyd too delivers the requisite thrills, spills and violence, as well as pitch-perfectly Bond’s ex-CIA agent chum Felix Leiter and curmudgeon boss M. Moreover, the minutiae of Bond’s London home life are given the full treatment, which is rather unexpectedly refreshing. And, rest assured, there’s also much attention paid to Bond’s delectations: food and drink (among them Boyd’s own recipes for a vodka Martini and a salad dressing); cars (here Jensens); cigarettes, clothes and weaponry. All vices very much intact then.

.

Chelsea not lately: James Bond’s stomping ground that’s the King’s Road cameos more than once in Solo, but the late ’60s, socially liberated version – what would Fleming make of it…?

But – and it’s a big but – Solo is less satisfying in two critical areas: the locations and the literary Bond’s glamour/ surreality. There’s nothing inherently wrong with sending our man to Africa and the fictitious war-ravaged country of Zanzarim (doing the latter allows the author artistic leg-room), but as the single setting for a long middle section of a Bond novel it’s pretty bleak stuff – starving kids even pop up. And, owing to this undiluted realistic setting, the villains our hero’s up against aren’t exactly the most electric – African warlords and savage white mercenary soldiers may be just as evil and physically threatening as an Auric Goldfinger or an Ernst Stavro Blofeld, but they’re less fantastic and fun, so ultimately less memorable.

Additionally, when we’re done in Africa, Bond, yes, ‘goes solo’ and travels to Washington D.C. His going AWOL in the films may be controversial (1989’s Licence to Kill, 2002’s Die Another Day and 2008’s Quantum of Solace), but Boyd knows what he’s doing with his admittedly convoluted plotting here, never allowing Bond to go full-Liam Neeson-in-Taken mode. Instead, it’s the use of Washington as the book’s secondary location that misses the mark.

Effectively a political capital with a dirty 1960s’ underbelly, Washington D.C.’s just rather dull for the Bondiverse. At times we get glimpses of the more exotic aspects of late ’60s Americana (assertive black women in afros and flares and red Mustang sportscars), but these are fleeting, surprisingly bringing to mind the cinematic Live and Let Die (1973) and Diamonds are Forever (1971) and thus making one ponder why Boyd didn’t go the whole hog and just send Bond to the then equally dirty but far more colourful and interesting New York City?

Ultimately, it feels a little unfair comparing a Bond continuation author’s effort to those of Fleming as surely no-one’s really going to deliver the genuine article again, but it’s both inevitable and necessary to do so. After all, as said, in significant areas Boyd is damn near spot on in Solo. So, will he succeed where Faulks and Deaver failed and get a second stab at the gig? Who knows. But there’s certainly a lot of promise here; his middle-aged 007 entering the ’70s could be intriguing (especially given the novel’s agreeable end coda), if only he could throw a little more of that Fleming glamour, dynamism and surreal magic into the mix.

.

This article was originally published on mi6-hq.com

.

Further reading:

.

Breakfast with Boyd: the launch of new James Bond continuation novel Solo (September 25/ The Dorchester, London)

Boyd, William Boyd: The new 007 author poses with BA brand ambassador Helena Flynn

If it’s good enough for James Bond then it’s surely good enough for representatives of the world’s press. William Boyd’s Solo opens with James Bond enjoying breakfast on his 45th birthday at The Dorchester, and so it was that journalists and photographers (including yours truly) crammed on Wednesday at 9am into the exclusive Park Lane hotel’s The Grill room to listen to what the latest 007 continuation author had to say at the launch of his bringing back Ian Fleming’s literary hero.

As revealed in the novel From Russia with Love (1957), breakfast is Bond’s favourite meal of the day, Lucy Fleming (his creator’s niece and board member of Ian Fleming Publications) reminded the gathered throng in introducing Boyd – and they were to enjoy a hearty morning with the author as he explained his love for the character and his approach to writing Solo before posing for the obligatory photographs.

His first encounter with Bond – as with so many 007 fans, no doubt – dates back to school, in his case Scotland’s Gordonstoun, where after lights-out he and his friends would read to each other (again) From Russia with Love as a “a kind of illicit thrill”. He was eager to stress he’s enjoyed several brushes with ‘Bondiana’ prior to this, having written films starring Sean Connery and Pierce Brosnan, directing Daniel Craig on-screen himself and even making Ian Fleming a character in his acclaimed novel Any Human Heart (2002). Although he’s always felt Daniel Day-Lewis would probably play a Fleming-faithful version of 007 best.

“It was a great experience and tremendous fun”, he said of this project. “I’ve always been extremely interested in Ian Fleming himself, the man. I re-read all the Fleming novels in chronological order, pen in hand, taking notes and learnt an enormous amount about Fleming’s achievement”.

.

All present and correct: the British Airways brand ambassadors and the Jensen Motor Club members (beside their cars) await the nod to start their very important missions…

Solo, he attested, will certainly adhere to the literary series’ tried and tested aspects. M, Felix Leiter and Moneypenny will all be present and correct, while there’ll be “a lot of eating and drinking, a lot of interest in clothes – Bond’s a sensualist – a certain amount of weaponry, automobiles and of course two beautiful women”. When questioned on the old-fashioned attitudes of Fleming’s hero, though, he teased his 007 may have moved with the times a little – the book is set at the height of the Vietnam War and protest movement in 1969 – and preferred to suggest that Bond enjoys “relationships with women” rather than the novels featuring “Bond Girls”. Yet, the hero will still drink and smoke and do “everything you would expect of the classic Bond”.

The year of the book’s setting also informed Boyd’s choice of locations. Having grown up in Africa himself, he was eager to send 007 to the continent (something Fleming only did once and briefly in 1956’s Diamonds are Forever) and the civil war into which Bond’s thrown in Solo’s fictitious African nation deliberately echoes Nigeria’s which was raging in 1969. The author also felt the fact he’s written two espionage novels was good preparation: “I certainly tackled this with confidence, in that I know how to construct a highly complex plot – I knew how to put the rhythms of suspense and complexity into the novel”.

And with that William Boyd was gone, off to cruise London on a publicity blitz in the model of Jensen car (an FF Mark I) that Bond drives in his novel. But not before he’d signed seven copies of Solo in front of the cameras, each of which was then sealed in a white Perspex box and handed over to a British Airways flight attendant (‘another great British brand’) whom would be whizzed away with it in one of seven handy Jensens parked outside The Dorchester to Heathrow’s Terminal 5 and on to flights bound for the Fleming and/ or Boyd-related international cities Amsterdam, Cape Town, Delhi, Edinburgh, Los Angeles, Sydney and Zurich. Sixty years after his first novel Casino Royale was published by Jonathan Cape, Fleming himself would surely have approved and maybe been amused by all the glamour, pomp and circumstance.

Indeed, Lucy Fleming commented on the symmetry of Solo being published by Jonathan Cape, for this was “the [publishing] house that produced those soft-paged, ink-smelling editions with the Richard Chopping covers that for so many people were their first introduction to James Bond”.

She added that Ian Fleming Publications were “flattered that not only an author as fine as Will should take up the baton of Bond, but that he should have done so with such panache. Solo is an excellent novel and one of which Ian would have approved heartily”.

.

This article was originally published on mi6-hq.com

.

Further reading:

.

.

.

.

.

.

Author: Gareth Roberts

Year: 2012

Publisher: BBC Books (Ebury Publishing)

ISBN: ISBN-10: 184990328x/ ISBN-13: 9781849903288

.

Thanks be to Rassilion, for in the wake of the UK (and, to some extent, the wider world) going truly Who crazy in recent years, the Beeb finally got its arse in gear last year and ensured the unfinished, never broadcast, should-have-been-awesome Douglas Adams-penned, Tom Baker-toting Doctor Who serial Shada (1980) has finally lived up to its potential and been realised in a wholly satisfying, entirely successful incarnation.

Over the years, Shada has (ahem) regenerated from its original TV story into an audio adventure (oddly with Paul McGann’s Doctor) and back to a very underwhelming, cobbled together DVD release of the original serial, but don’t doubt it, happily Gareth Roberts’ novel(isation) of last year can absolutely lay claim to being the definitive version. This literary Shada from Roberts then (‘NuWho’ scribe of 2007’s The Shakespeare Code, 2008’s The Unicorn And The Wasp, 2010’s The Lodger and 2011’s Closing Time and script editor of 2007-11’s spin-off series The Sarah Jane Adventures) is the only one to realise the sadly deceased Adams’ vision. That’s to say, it’s an adventuresome, acerbic, silly, very funny and very polished biblio-centric version of Shada that’s surely the triumph Adams could only have dreamed his TV serial would be.

The fate of the original Shada‘s a sad one – not least for Baker fans. Given the transitory, disappointing and, well, pretty crappy nature of the thesp’s final season on the show (1980-81’s Season 18), he and his fans should at least have enjoyed, in the shape of his penultimate season’s final serial – yes, Shada – a last hurrah. But thanks to industrial action affecting the BBC (this was the fag end of the ’70s/ the ’80s’ crap new dawn), that was never to be; Shada didn’t see its filming finished, let alone get broadcast. Alas, indeed. For here was a four-part story that on paper (or, rather, on the page) rivaled the blissfully brilliant story City Of Death (1979) from earlier in its season.

Like City Of Death, it too of course was written by The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide To The Galaxy supremo Douglas Adams (Doctor Who‘s then script editor), and like that serial too (and Hitch-Hiker’s) featured a clever-clever, twisty-turny, space-travel-meets-time-travel-meets-marvellously-mundane-Britishness plot and comic sensibility. The ‘Britishness’ came courtesy of its major setting being a Cambridge University college, itself a hotbed of eccentricity and the unique, of course, if nicely humdrum when compared to the colliding glamour and adventure of The Doctor’s universe-wide world.

But fast-forward over 30 years into the future and, yes, Shada is now back in book form. The plot’s exactly the same – testament indeed to Roberts wisely trying to keep the novel as faithful to the original script and as, well, Adamsian as possible. It’s, yes, 1979 and Baker’s Fourth Doc and Lalla Ward‘s Romana (II) are visiting Cambridge college St. Cedd’s, as they’ve been messaged by a certain Professor Chronotis that he wants to see them. Only the highly forgetful, very old and loveably doddery Chronotis doesn’t remember sending them a message at all.

.

.

And just as our hero wonders who did and, more worryingly, why they did, so appears on the scene a jumped up, ludicrously dressed but brilliantly intelligent psychopathic alien named Skagra, whom in addition to stealing other genius’s minds with a silver spherical globe device, wants something Chronotis has. It couldn’t be a particular book the old duffer (whom, worryingly but most intriguingly, it turns out is a retired Time Lord) allowed a lovelorn postgrad scientist Chris Parsons to borrow in order to impress his would-be girlfriend, but has suddenly discovered can seemingly bring to life memories, fantasies and things that may happen in the future, could it? No it couldn’t be that. Surely not…

Shada‘s success lies in its marvellously well honed, irresistible combination of the familiar and the unexpected. First, the familiar. The protagonists here could only be the Baker and Ward incarnations of The Doctor and Romana, respectively (him full of gleeful-abandon one-second, oh-so-sober-cosmic-caretaker-foreboding the next with his daft curls, even dafter boggle eyes and even dafter never-ending scarf; she with her delightful aristocratic angelic air that all but overpowers poor Chris Parsons); K-9 could only be the incredibly intelligent, incredibly useful, but also incredibly dangerous robot dog he is and the TARDIS could only be, well, the TARDIS. So far so good; Roberts truly deserves a medal for bringing to life the late ’70s Doctor Who so fondly, amusingly and satisfyingly with these perfectly realised tenets.

Yet now we come to the unexpected, for its here that Shada earns its stripes just as much, if not more. Unlike – what was filmed of – the original TV serial (see above video clip), Roberts absolutely nails the characters of Parsons, Claire Keightly (his love interest), Chronotis and despicable baddie Skagra, their respective worlds and their collective importance and driving nature to the overall plot. In short, Shada is far from just The Doctor, Romana And K-9 Show. The original serial sees a Chris Parsons (played by Waiting For God‘s Daniel Hill) whom seems rather too old and smooth to be the socially awkward and even more amorously awkward postgrad of the story. Here, Roberts puts that utterly right and, in doing so, turns the character into an Arthur Dent-esque bemused, nicely comic soundboard for the audience (masquerading as a human ally for the heroes). Additionally, it’s utterly obvious why Chris has fallen for Claire; she’s everything he’s not, confident, resourceful, forceful and quick-witted – at one point (thanks to a bit of hypnotism) she even rivals Romana in the indispensable companion stakes.

Chronotis too is a far more satisfying character here than in the original serial; a quirky, adorable old grandpa figure whom you get the idea maybe hides an extraordinary secret, not just an estimable bookcase-cum-TARDIS and a big penchant for tea. But, perhaps most memorable of all, is Skagra, a wonderful villain of the piece. Blessed with a huge intellect, an amazing propensity to build 2001: A Space Odyssey-style spaceships, ruthlessly cold and totally bonkers (rather like The Big Bang Theory’s Sheldon Cooper gone very, very wrong). Yet his best moment may just come when a street yob compares his unwittingly ridiculous get-up to that of ’70s funkster Disco Tex (“How’s the Sex-o-lettes?” – priceless).

Apparently, Roberts felt he would have to fix one or two plot holes when he went through the original serial’s scripts to write his adaptation – no wonder then the plotting’s so tight and the story’s final, almost devastating complication (accompanied, fittingly, by what we may assume is a Gallifreyan swearword on the Doctor’s lips) so effective. Speaking of such humour, the author indulges in further Adamsian humour by coming up with a wonderful near ethereal character in the shape of the pseudo-consciousness of Skagra’s awesome spaceship – it’s a wonderful echo of Hitch-Hiker’s Marvin the Paranoid Android. Indeed, you’d never realise it (always the mark of a good writer and a well edited novel this), but apparently as he started adapting Shada, Roberts found it a task far more difficult and far more time-consuming than he’d thought it would be. Just goes to show, then, that if it’s tough work, like The Doc when we first meet him on a boat on the River Cam, some things are very much worth a punt.

.

Further reading:

Shada’s page at BBC Books/ Ebury Publishing

.

.

.

Tardis Party: Doctor Who serial close-up ~ City Of Death (Season 17/ 1979)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

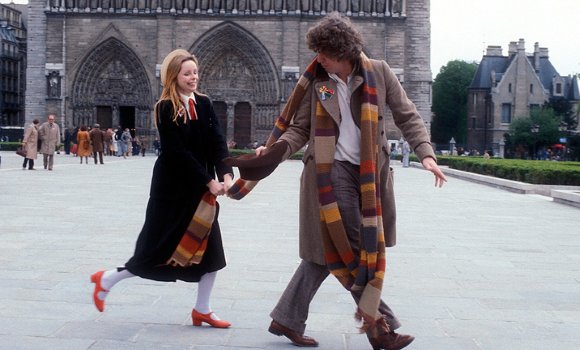

Paris pair: “You know, in some cultures, pulling my scarf like that would mean we’re married…”

For many not particularly, er, versed in the ‘Whoniverse’, Doctor Who seems to have offered never-ending lashings of humour, far-fetched fantasy and silly looking aliens, but it wasn’t always so. By the late ’70s, however, after the ace behind-the-scenes team of producer Philip Hinchcliffe and script editor Robert Holmes had shuffled on, the show was in the hands of producer Graham Williams and – maybe or maybe not – under pressure from the likes of ‘Clean up TV’ campaigner Mary Whitehouse, had noticeably toned down the high thrills and mild horror and upped the comedy and camp – and many a Who fan wasn’t that impressed.

The show itself wasn’t suffering awfully in the ratings, though, while the introduction in 1977 of the irresistible robot dog extraordinaire K-9 had surely been all kinds of wonderful, and this era enjoyed its unequivocal crowning glory in the Paris-set, post-modern marvel that is City Of Death. Hopefully then, this post (the latest in George’s Journal‘s current celebration of the sci-fi giant’s golden anniversary) proves just why this serial is just as much a masterpiece as any of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisas…

.

.

.

Doctor: Tom Baker (The Fourth Doctor)

Companion: Lalla Ward (Romana II)

Villains: Julian Glover (Count Scarlioni/ Captain Tancredi/ Scaroth); Catherine Schell (Countess Scarlioni)

Ally: Tom Chadbon (Duggan)

Writers: Douglas Adams, Graham Williams and David Fisher (all credited as ‘David Agnew’)

Producer: Graham Williams

Director: Michael Hayes

.

.

.

.

.

.

Season: 17 (second of five serials – four 25-minute-long episodes)

Original broadcast dates: September 29-October 20 1979 (weekly)

Total average viewers: 14.5 milion

Previous serial: Destiny Of The Daleks

Next serial: The Creature From The Pit

.

.

.

.

.

The Doctor and his current companion Romana (a Time Lady from his own planet Gallifrey) are relaxing atop the Eiffel Tower while on holiday in Paris. They agree the French capital is so agreeable because it has ‘a bouquet’ – ‘like a fine wine’, The Doctor adds, but concedes the year of their visit, 1979, is ‘more of a table wine really’. As they sit down to lunch in a café, Romana is intrigued an artist is sketching her – and turns around to see. Aggravated by her spoiling her pose, the artist leaves in a huff and tosses away the sketch. Just as he gets up to examine the discarded paper, The Doctor experiences ‘a turn’ – in fact, more than that, as the last few seconds for him, Romana and us replay themselves. Fully aware of this (unlike any of the humans around them), the pair become concerned as they look at the sketch; instead of Romana’s face it features a clock face with a crack through it – ‘a crack in time…’ muses The Doctor.

Meanwhile, in the cellar of a château across town, a Professor Kerensky has just demonstrated what his highly advanced and highly expensive scientific equipment is capable of to his employer – and the château’s owner – Count Scarlioni. The latter, smooth as silk, enigmatic and devious, isn’t impressed, however, and emphasises the need for improvement and urgency – he wants the next test the following day; ‘it’s a matter of time‘, he says. The Doc and Romana have by now made their way to the Louvre art gallery and are examining Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, as the former wants to show the latter the exquisite art humanity is capable of. Nonplussed, Romana declares it merely ‘quite good’.

Just then, another time distortion – or time slip – occurs, The Doctor ending up on a nearby bench in the corridor, next to an attractive, dignified woman wearing a gaudy bracelet and his head resting against a man in a trenchcoat. The latter asks him whether he is all right, to which he replies ‘my head dented your gun’ (the one in his trenchcoat pocket, that is). Away from the Louvre, The Doctor reveals to Romana he half-inched the woman’s bracelet and placed it in his companion’s pocket. The latter examines it and comes to the same conclusion as he did in the Louvre – the bracelet did not originate on Earth.

The Doc belives it’s a micromeson scanner, which the woman was using to monitor the art gallery’s alarms. Joined by the chap in the trenchcoat now, who’s followed them, they warn him she (and probably others) plan on stealing the Mona Lisa. This piques the former’s interest, a detective named Duggan, for his task it is to put an end to a spate of extremely valuable works of art being stolen while brilliantly impressive fakes are put in their place. He also reveals the woman in the Louvre was Countess Scarlioni, wife of the Count, one of the richest and most notorious men in the world. Quickly, the trio are faced at gunpoint by thugs, while back at the château, the Countess, having on her husband’s orders sent the thugs to apprehend the three (whom she assumes stole her bracelet), is looking for her husband. Behind a locked door, the Count stands now before a mirror and opens up his face to reveal the green-skinned, one-eyed head of an alien.

Countess Scarlioni: [Referring to The Doctor] My dear, I don’t think he’s as stupid as he seems

Count Scarlioni: My dear, nobody could be as stupid as he seems

Taken by the thugs to the château, The Doctor, Romana and Duggan are presented to the Countess in the drawing room; The Doctor being pushed into the room (and to the floor) by a henchman – ‘what a wonderful butler,’ The Doc observes, ‘he so violent!’. As he tries to feign knowledge of what she and the Count are probably up to, Romana picks up a Chinese puzzle box. The Countess informs her it’s impossible to work out the correct combination of sliding components to open it; using her intellect, Romana delightedly opens it on her first attempt and, from it, the bracelet falls into her hand. The Count enters and relieves her of the bracelet, ordering for his opponents to be locked up in the château’s cellar. Duggan picks up a chair to defend himself from the Count’s goons and, seemingly horrified, The Doc asks him what he’s doing – ‘that’s a [priceless] Louis Quinze chair!’ he exclaims.

Using his sonic screwdriver to ensure their escape from the cell, the trio investigate their surroundings, The Doc intrigued by Kerensky’s scientific equipment and Romana working out that there must be a secret room walled-up behind the cell. Just then, Kerensky returns to the cellar and undertakes another test, a seemingly fascinated Doctor happily watching. The experiment sees an egg hatch into a chick, which within seconds grows to a full-sized chicken which then rapidly dies and becomes a skeleton. This is an experiment in time then – on the orders of the Count, of course. The Doc, however, points out it’s not actually a success and reverses the chicken’s existence before the professor’s eyes, claiming it’s dangerous dabbling with time if you don’t actually know what you’re doing.

Stubbornly (and unnecessarily), the ‘force always first’ Duggan knocks out Kerensky and somewhat redeems himself by launching himself against the cell’s wall to ensure the trio manage finally to break through and discover what the secret room conceals – but they’re far from prepared for it. Inside a cupboard they discover a Mona Lisa, which (owing to him having spent time with Leonardo da Vinci, thus becoming an expert on his style and work), The Doctor claims is genuine, then finds five further versions of the painting and declares they’re all genuine too. Duggan is confounded, but points out that if a Mona Lisa were hanging in the Louvre, no-one would buy a fake unless they thought they were getting a real one.

Unbeknownst to them, Scarlioni has joined them in the secret room, taking pleasure in their shock discovery, at which point Duggan characteristically knocks him out so they might escape the château. The Doc leaves Romana and Duggan and scarpers across town to the TARDIS, in which he sets the co-ordinates for Florence, Italy… in the year 1505. He steps out into an artist’s billet, taking in the glorious Renaissance sunshine through its window, before he’s faced by a sword-carrying guard, whom claims Leonardo da Vinci isn’t home because he’s engaged in important work for Captain Tancredi. The Doctor clearly does not know who this is, but immediately finds out as an elegantly dressed soldier walks into the billet – with the face of the Count. The Doctor asks what he’s doing here, to which the Count replies ‘I think that is exactly the question I ought to be asking you, Doctor…’

.

.

Despite having been put in thumbscrews to find out how he’s managed seemingly to be in two places at once, The Doc manages to elicit from his captor how he’s managed literally to achieve that very feat – for the latter can’t help boasting to the former. He says he’s in fact Scaroth, the very last of the Jagaroth. The Doctor has heard of this race; having nearly wiped itself out in a war 400 million years ago, their tiny number of survivors travelled to Earth, which was in a lifeless state. Here they were believed to have finally snuffed it when their spacecraft exploded on take-off from the planet’s surface. What actually happened, however, was that Scaroth survived the explosion – albeit his existence was compromised, as splinters of his being were scattered across Earth’s future time and space; all of them identical, yet none complete. Eventually, his captive is forced too to explain his secret (he can’t stand being tortured by the guard’s cold hands, which are holding the thumbscrews); he tells Scaroth he’s a Time Lord and Romana a Time Lady and then asks the latter how he manages to communicate with his other selves – only to receive an instant, unexpected demonstration.

As he watches, the ‘Tancredi version’ of Scaroth holds counsel with his other ‘splinters’ (the ‘Scarlioni version’ of 1979’s Paris interrupting a discussion with the Countess, whose goons have just successfully stolen from the Louvre its Mona Lisa for them). Owing to the almighty effort this requires Scaroth, The Doctor is able to use this distraction and flee, having earlier (while Scaroth was out of the billet and the guard knocked out) found Leonardo’s original Mona Lisa and identified the canvases on which the artist would paint for Tancredi the further Mona Lisas to be found in the future, he then wrote on each of them the legend ‘This is a fake’ – so they might be assumed as such under examination and scupper Scarlioni’s thieving scheme – and left an explanatory note for Leonardo in the latter’s favoured code of backwards writing.

Safely inside the TARDIS now, he observes on its scanner 12 versions of Scaroth appearing and converging (including one from ancient Egypt, another from Neanderthal times, another from the far future and another that looks suspiciously like Julius Caesar). (The) Scaroth(s) are blathering on about masterminding the building of Pyramids, discovering fire, inventing the wheel and pushing forward the entire human race to save his own – clearly his grand art thefts (using alien technology such as the bracelet) have financed his time experiments via Kerensky, whose intended result is to ensure he can return to the moment before the Jagaroth spaceship exploded, so he can save the race and unite his splintered selves. Unfortunately, he now knows of both The Doctor and Romana’s time-travel knowledge.

For her part, Romana, with Duggan in tow, has returned to the château; the two of them deciding, as they have found out the Louvre’s Mona Lisa has been stolen, the best thing they can do is to hunt for the real painting – if the Louvre’s is the real one. Once there, they’re immediately captured by Scarlioni’s guards once more and, having been taken back down to the cellar, Scarlioni/ Scaroth enjoys informing them he now knows from The Doctor himself that Romana’s a time-traveller and can aid him in his quest. If she refuses, he’ll use Kerensky’s equipment to destroy Paris. Duggan doesn’t believe any of this, but Romana assures him their captor can do what he’s threatening. Kerensky, though, desperately pleads for all his work and equipment not be used for such malevolent purposes, at the sound of which his employer orders him to stand in the centre of the equipment and check it’s working properly, giving the evil alien the chance to do away with the now unnecessary Kerensky – he switches on the machine and the hapless professor ages at a staggeringly rapid rate, ending up nothing more than a skeleton.

Romana: You should go into partnership with a glazier. You’d have a truly symbiotic working relationship

Duggan: What?

Romana: I’m just pointing out that you break a lot of glass

[She puts a pair of wine glasses in front of him; instead of opening the wine bottle he smashes the neck off it]

Duggan: You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs

Romana: If you wanted an omelette, I’d expect to find a pile of broken crockery, a cooker in flames and an unconscious chef

Scarlioni/ Scaroth declares Kerensky was killed because the equipment’s ‘time field’ is unstable. Whether or not the first part of this statement is true, Romana knows the second part is. She has no alternative then to help him and alter the equipment so it’s safe when operated. Meanwhile, The Doctor has returned to the château and faces the Countess, he casually informs her that a green, one-eyed alien is ransacking the art world to save his species. He is taken down to the cellar, but has unnerved the Countess and got her thinking… she retrieves from a cabinet an Egyptian scroll that features several gods, one of which has a green, one-eyed head.

In the cellar, it appears Romana’s finished her work, ensuring the equipment is ready to be used to send its owner back through time. The evil alien then enters the drawing room to bid farewell to his wife. She levels a gun at him and demands to know just what he is. He smoothly tells her it was easy to deceive her – a fur coat here, a trinket there – and removes his ‘face’ to reveal his green, one-eyed true form to her for the first time. Then he suggests it was kind of her to keep wearing the bracelet; he activates it, instantly killing her – ‘goodbye, my dear, I’m sorry you had to die, but then, in a short while, you will have ceased ever to have existed’. Back in the cellar, Scaroth steps into the centre of the equipment and disappears back through time, only too aware that Romana has rigged the thing so he can remain in his destination only for a few seconds before he has to return, but he only needs a few seconds. Duggan, relieved, believes it must now all be over and they can relax and go for a drink, yet his two companions declare they must go on a journey.

As The Doctor and Romana return to the TARDIS, taking Duggan with them then, the former pilots the machine after the ‘time trace’ left by Scaroth’s journey. The three step out of the time- and space-machine on to barren rock, which The Doc declares is a point that in the future will be at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, but is now 400 million years into the past. He spies the Jagaroth ship of which Scaroth spoke and, nearby, a soup of slurry that contains the amniotic fluid from which all life on Earth will begin. Romana notices the ship’s thrust motors are damaged and when its pilot (the ‘past’ Scaroth) attempts to take-off it’ll explode; the Doctor realises in fact this explosion didn’t just splinter Scaroth through time, but also the radiation thrown out from it ignited the slurry of fluid and kick-started life on Earth. Scaroth must absolutely be stopped from preventing his ‘past’ self from trying to take-off in the ship!

Speak of the devil and, well, the devil appears, fresh from travelling back through time too. As he calls to his fellow Jagaroth not to take-off, The Doc cries that he’s rolled the dice once and doesn’t get another chance – or at least doesn’t deserve one. Duggan, however, reverts to type and simply knocks out Scaroth; this time to The Doctor’s delight – ‘Duggan, I think that was possibly the most important punch in history!’. Scaroth’s time is up and he disappears, travelling back to the future, where (back in the château) his reappearance as a monster causes his henchman to destroy the equipment, blasting Scaroth out of existence and starting a major fire. Back in the past, the trio hurry back into the TARDIS just before the Jagaroth ship attempts to take-off and explodes in a fireball, in turn of course, beginning life on Earth.

Later, atop the Eiffel tower once more, The Doctor attempts to convince Duggan that just because the only one of the seven Mona Lisas to survive the fire in the château has ‘This is a fake’ scrawled on the canvas, underneath the painting, doesn’t make it any less the genuine article – after all, it was undoubtedly painted by Leonardo. If the authorities x-ray the portrait and discover the writing, it serves them right – why should they have to examine such a work so closely to deem it great art, instead of merely looking at it and appreciating it? The two Gallifreyans bid Duggan goodbye and the latter picks up a postcard of the Mona Lisa from a stall next to him, ruefully looking down at the image.

.

.

.

.

Not only is City Of Death the funniest, it’s also by far the most popular (on original showing) and easily one of the absolute very best Doctor Who serials – and probably my favourite story of the original ‘Classic’ series too. How could you not be pulled in, enthralled and delighted by a four-parter that features ‘ultimate’ Doc Tom Baker with arguably his ultimate companion (a fellow Gallifreyan who’s the cute as a button Lalla Ward; on whom the actor unquestionably had his eye, so much so they got together and eventually married – see bottom video clip) gallivanting around the practically perfect Paris, with a hapless, loveable detective for an ally and a desperate monstrous-looking monster hiding in human form as a suave villain, with his equally charming, aristocratic wife. Oh, and seven – count ’em, seven – Mona Lisas thrown into the mix too.

The primary reason why the serial’s such an utterly entertaining and satisfying entry in the Who canon, though, is the quality of its writing. Unmistakably scripted by Douglas Adams, its story and dialogue has all the hallmarks of The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide To The Galaxy legend. Undoubtedly, this is Doctor Who as comedy, but Adams’ brilliance isn’t in just writing a thoroughly funny serial, it’s perhaps more so in how he makes it funny.

His script doesn’t so much wallow in the died-in-the-wool and/ or far-fetched fantasy conventions of Who (a rather ridiculous-looking alien; the fact The Doc can go back in time to meet and become chums with Leonardo da Vinci; he and his companion are ‘assisted’ by a slow-on-the-uptake, often useless ally), it delightfully plays around with these conventions (the alien has been hiding as a member of the human race, which he’s deliberately pushed forward in development; The Doc tries to scupper the alien’s scheme of forcing Leonardo to produce a multitude of Mona Lisas by writing on their pre-painted canvasses in, yes, felt-tip and the slow, useless sidekick is a p*ss-take of the Bulldog Drummond-esque trenchcoated detective of pulpy action fiction – his fists-first approach a running gag that always delivers). The clever fooling about even extends to the serial’s title – in the language of its setting City Of Death translates as ‘Cité de la mort’, which sounds an awful lot like ‘Cité de l’amour’ (‘City of Love’, a nickname for Paris). In short, in this story Adams gives Doctor Who the entirely effective post-modern treatment. Never since has the show taken the mickey out of itself – and screen adventure drama in general – with such smarts, confidence and swagger.

Adams’ script isn’t confined just to comedy, though, for the pacing throughout the four episodes is pitch-perfect and the cliffhanger to Episode Two one of Who‘s very best; revealing a villain in Renaissance Florence who’s troubling Leonardo to be exactly the same villain troubling The Doctor and his mates in the present. What the hell! And the explanation for this in Episodes Three and Four is even better – the villain’s entity is scattered throughout time, so versions of himself exist in different eras and places at exactly the same time. It’s almost breathtaking (like the cliffhanger) on first viewing – and so good is it, current ‘NuWho’ show-runner Steven Moffat seemingly borrowed it for the explanation of companion Clara’s mystery in latest episode The Name Of The Doctor (2013). And, let’s not forget too, that nicely-slid-in theme of what constitutes great art, which The Doc, Romana and Duggan disagree over throughout the adventure – all those Mona Lisas, which one’s tops if they’re all Leonardo’s? And what so great about them anyway?

Mind you, City Of Death isn’t just The Douglas Adams Show. Director Michael Hayes does an excellent job in realising the script’s humour, twists and turns and ambitions. Plus, while clearly relishing the story and comedy, Baker’s in his element as our hero, as is Ward as companion Romana. Moreover, the casting of quality, familiar TV faces Julian Glover and Catherine Schell as the villain and villainess is up there with the best guest casting in the show’s history (cf. Christopher Benjamin and Trevor Baxter as Jago and Litefoot in 1977’s The Talons Of Weng-Chiang) and Tom Chadbon’s Duggan makes for a fine foil to all the sci-fi-informed characters around him.

And special mention too must go to a pair of Who story facets that rarely get acknowledged, namely the music and the locations. City Of Death was – maybe surprisingly, given its era of production was the economically depressed, fag end of the ’70s – the first Who serial to feature overseas filming and a good deal of it at that; the Parisian locales adding (up to that point) unique, nay unparalleled atmos, style and class to proceedings (‘a bouquet’, you might say). And regular incidental music composer Dudley Simpson’s work is particularly satisfying – and unusually memorable. The theme that plays over The Doc, Romana and Duggan’s haring around Paris’s streets complements the on-location work perfectly, even adding the mostly comedy-first story an authentic, thriller-esque dimension.

The final word here, though, has to go to those unforgettable few seconds right before the story’s final climax – those two art lovers’ utter guff over why the TARDIS is such a deserving ‘modern art’ piece belonging in the gallery in which The Doc’s parked it (see video clip above). This double cameo from John Cleese and Eleanor Bron, brilliant veterans of British screen comedy already by this point, add a totally unexpected but utterly perfect moment as The Doctor, Romana and Duggan sweep past them, into the TARDIS and the latter disappears. It’s the quintessential example of Doctor Who stepping out of itself and straight back in that this serial is all about.

.

.

.

.

.

As so often with great Who stories of lore, the omens weren’t good for City Of Death. It began life as The Gamble With Time, a 1920s-set adventure in which an alien poses as a human playboy whose wife’s gambling finances his time experiments. It was conceived by David Fisher, author of the previous season’s efforts The Stones Of Blood and The Androids Of Tara (both 1978). Fisher, however, was going through a particularly messy divorce when called on by producer Graham Williams to deliver a final script, in which case then the task of delivering it fell to Williams’ script editor Douglas Adams.

The latter, after struggling for years, had at last – and all at once – landed on his feet. He was fresh from his big success with The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide To The Galaxy radio series (1978), plus had just seen his set-to-be-even-bigger-success, the book based on the former, published, and was now of course slogging away as the official overseer/ re-writer of Who‘s scripts. And this particular re-writing job truly was one, requiring Adams to churn out four 25-minute-long episodes in practically no time at all. He was then, clichéd as it may be, holed up in Williams’ home and, fuelled by whisky and coffee, somehow managed to get it done in a single weekend. The rest, of course, is history. So much so, in fact, that Adams re-used elements of his script for that of his fellow brilliant (but ultimately only half-filmed) effort this season Shada (1979) and his later novel Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency (1987).

Although filming overseas – not least in a place as aspirational (to the late ’70s British mentality, no doubt) as Paris – was an exciting first for Doctor Who, the reality was far from glamorous. Not only was there a lot of rain, the schedule forced the crew to cross the channel on May Day weekend when many establishments were closed – even a pre-selected café, the rattling of whose door-handle during one scene caused the business’s alarm to go off and the thesps and crew to, well, have to scarper. Also, according to a later interview with Adams, along with Ken Grieve, director of the next story to be filmed that season (Destiny Of The Daleks, which was broadcast directly before City Of Death), on an impulse he jetted off to Paris because he hadn’t been invited to the ‘glamorous’ location. Once they got there, though, neither found themselves particularly welcome as everyone else was hard at work. The pair then spent the evening and night drinking in Parisian bars before flying back to Blighty – essentially, for Adams’ part, so he could boast to anyone who’d listen in BBC TV Centre next day what he’d just done.

Cast-wise, City Of Death affords Who two of its strongest connections to the world of 007 (one of any number of reasons why I love this story, must confess). Both Julian Glover (Scarlioni/ Tancredi/ Scaroth) and Catherine Schell (Countess Scarlioni) would feature or already had featured in supporting roles in James Bond films; Glover as similarly smooth villain Kristatos in For Your Eyes Only (1981) and Schell as one of Blofeld’s delectable ‘Angels of Death’ in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969). Moreover, Glover had already played Richard The Lionheart in the Who story The Crusaders (1965) and would achieve maximum fame as General Veers in The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and as, yes, smooth villain Walter Donovan in Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989), while Schell had co-starred opposite Peter Sellers in The Return Of The Pink Panther (1976) and as a regular player in Gerry Anderson’s TV series Space 1999 (1975-78).

Worth noting too is the fact John Cleese and Eleanor Bron were roped into making their cameos thanks to Douglas Adams knowing them from his Cambridge Footlights days and working – certainly with Cleese – on Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969-74). Lalla Ward, however, had nobody but herself to blame for the highly flattering letters she received from many a red-blooded male thanks to choosing to wear a schoolgirl’s uniform costume throughout – she apparently, and most naïvely, did so because she hated wearing them at school and thought girls watching the programme would enjoy doing the same more if they saw Romana in one.

The boast above that, in terms of original broadcasts, City Of Death remains the most popular Who serial ever isn’t an idle one. Its average audience (across all four episodes) of 14.5 million is exceedingly high in itself, but was boosted by the – now astounding – 16.1 million peeps who tuned in to watch Episode Four (comfortably the highest ever viewing figure for any Doctor Who broadcast) on October 20 1979, albeit a Saturday night when owing to industrial action ITV was forced into a black-out.

All in all then, although City Of Death dates from the much maligned humour-centric, Graham Williams-produced late era of Tom Baker’s tenure, there can surely be no question this generally derided time in the show’s history was well worth it, yes, for all its flaws and false notes, given it gave us this biggest, (possibly) best and definitely funniest of Doctor Who efforts. In the words of Eleanor Bron, exquiste… absolutely exquiste.

.

.

.

Next time: The Five Doctors (Special/ 1983)

.

Previous close-ups/ reviews:

The Talons Of Weng-Chiang (Season 14/ 1977/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

The Deadly Assassin (Season 14/ 1976/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

Pyramids Of Mars (Season 13/ 1975/ Doctor: Tom Baker)

Genesis Of The Daleks (Season 12/ 1975/ Doctor: Tom Baker)