David Niven: the gent’s centenary

So, it’s officially spring in the Northern Hemipshere. Good news too, given we’ve had a pretty heavy winter here in Blighty. And what’s it like out today? Are lambs to be seen leaping in lush, green meadows? Are daffodills sprouting all over the shop and turning the land yellow? Are rabbits, er, you know… like rabbits? Well, a quick look out of the window tells me… no. Looks like it’s going to be another cloudy, sorry, rainy day again.

And, in any case, did spring start this weekend? I was always under the impression it began on the 20/21 March, the date that’s halfway between the winter and summer solstices, but it seems nowadays many – especially in the media – don’t go by that anymore and just state that spring officially starts on 1 March. Hmmm, odd. Who knows?

Oh well, at least I found out, literally today, that there is something we can celebrate, all optimistic-like, with it being the beginning of spring (whether it happened this weekend or 1 March), because on the first day of this month, had he lived, David Niven would have reached the milestone age of 100 years young.

Yes, Niv. Hollywood’s English gent extraordinaire and genuine wartime hero, serving with the British commandos during World War Two, as he did. Methinks it’s almost impossible not to admire and like him; he had an endearingly easy-going air on screen and a wicked, wonderful wit that went hand-in-hand with his reputation as a first-rate raconteur.

Niven was born on 1 March 1910 in London and, following generally unhappy spells at British boarding schools, he drifted into the army. Discovering that wasn’t to his taste either, he jacked it in and fled to the US. After a few oddjobs (including cleaning and polishing rifles for hunters in Mexico) he found his way to Hollywood in 1933. There, he won himself a contract under legendary producer Samuel Goldwyn, which saw him appear in films like The Charge Of The Light Brigade (1936), The Prisoner Of Zenda (1937), Wuthering Heights (1938) and Raffles (1939), in which he played the lead. At this time, he shared a house with hell-raising heart-throb pal Errol Flynn, which they nicknamed ‘Cirrhosis-by-the-sea’.

Then the war came. He returned to the UK and was re-commissioned as a lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade in February 1940, before transferring to the commandos. He took part in 1944’s Normandy Landings, although he went over to mainland Europe a couple of days after D-Day (4 June), and in working with the Army Film Unit, he made two (essentially) propaganda pictures for the British war effort, The First Of The Few (1942) and The Way Ahead (1944).

“Look, you chaps only have to do this once. But I’ll have to do it all over again in Hollywood with Errol Flynn!” ~ Niven to his men, as he was about to lead them into battle in the Second World War

Following the war, he was out in the wilderness for a few years when it came to Hollywood, but during this period he starred in Powell and Pressburger’s British masterpiece A Matter Of Life And Death (1946), in which he played a downed RAF officer convinced he shouldn’t be sent to heaven but allowed to live again. Back in the US, he returned to the big time by playing Phileas Fogg in the multi-Oscar-winning Around The World In 80 Days (1956), and his star coninued to rise with his role in Separate Tables (1958) winning the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Combining TV work with his film career, he went on to star in another 30 movies – most notably The Guns Of Navarone (1961), The Pink Panther (1963), the poorly received spoof Bond Casino Royale (1967), Murder On The Orient Express (1976), Candleshoe (1977), Death On The Nile (1978), Escape To Athena (1979), The Sea Wolves (1980) and the final two underwhelming Pink Panther sequels Curse of the Pink Panther (1982) and Trail Of The Pink Panther (1983). By this time, in his seventies as he was, he was beginning to suffer from ill health – amyotrophic lateral schlerosis, to be exact. Sadly, it was from this disease he died on 29 July 1983 at his Swiss chalet home.

He was married twice; first to the wondefully named aristocrat Primula Rollo (1940–46), and following her death owing to a tragic accident at the home of film star Tyone Power, second, to Swedish model Hjördis Tersmeden (from 1948 until his own death). Theirs was a stormy marriage, with affiars on both sides (his reputedly including both Grace Kelly and Princess Margaret); she didn’t even attend his funeral and, upon her death in 1997, was not buried alongside him. He was survived by two sons, two adopted daughters (one of whom is believed to be his biological daughter out-of-wedlock) and four grandchildren.

Niv led – and had – a full life of dramatic highs and lows; fittingly so for one whose star shone as brightly as his did in the 20th Century’s firmament. He’ll always be remembered as the epitome of the unflappable English gent and as one of the greatest and funniest of storytellers – indeed, don’t take my word for it, check out his two outstanding, best-selling autobiographies The Moon’s A Balloon (1973) and Bring On The Empty Horses (1975).

So, thanks for all the memories, Niv – here’s to your life and marvellous times…

George

Listen, my friends!

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, click on the links, listen away and enjoy…

~~~

Moby Grape ~ Omaha

Dusty Springfield ~ I Don’t Want To Hear It Anymore

The Rolling Stones ~ She’s A Rainbow

The Small Faces ~ Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake

Crosby, Stills & Nash ~ Carry On/ Questions

The Doors ~ Hyacinth House

Todd Rundgren ~ I Saw The Light

Uriah Heep ~ Traveller In Time

The Walker Brothers ~ No Regrets

Kate Bush ~ Cloudbursting (Donald Sutherland!)

The Cars ~ Drive

Mental As Anything ~ Live It Up

The Housemartins ~ Think For A Minute

Brian Duffy: The Man Who Shot The ’60s

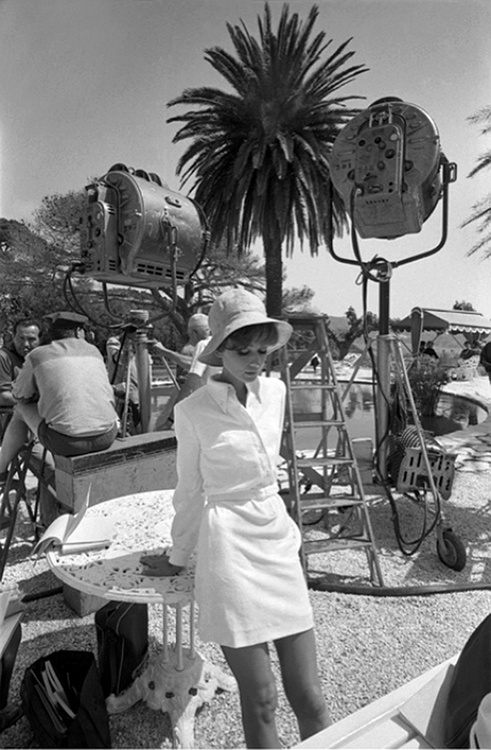

Blow up: Duffy and assistant at work as a model strikes a pose

Hands up who’s heard of the photographers David Bailey and Terence Donovan. No problem there, right? Now, hands up who’s heard of the photographer Brian Duffy. Yup, as a great fan of the culture of the ’60s, rather shamefully, neither had I. For, while Bailey and Donovan became household names, fellow working-class-snapper-done-good Duffy more quietly went about playing a big role in launching the career of Joanna Lumley, producing an iconic album cover for David Bowie and creating some of the most startlingly original ad design work that’s ever been seen.

He may’ve done this relatively quietly, but, according to a BBC4 documentary I saw the other night (why are so many of the really good ones nowadays limited to this channel?), he was anything but quiet in the flesh. Indeed, Duffy was, as the cliche goes, ‘difficult’ – obstinate, blunt, occasionally cruel and pretty sweary. But, hey, he was a top photographer back in the day when it was the snappers, not the models, who were the stars. And he was dry, funny and damn good, so he could certainly get away it.

He started out in fashion and only drifted into photography when he realised he needed a steady job to support his young family and photographing models for a living meant he could combine his love of art, fashion and gadgets. Indeed, his first assignment for British Vogue magazine saw him snap a high-profile conductor; only at the end of the shoot did the snooty subject inform the Cockney Duffy he’d forgotten to take the lens cap off. In spite of such inauspicious beginnings, he rose to become a star snapper in the early ’60s, just when fashion photography was becoming liberated thanks to the style of women’s clothing itself transforming into something more exciting, sexier and, in some cases, shorter than it had ever been before.

Mother and son: Duffy’s portrait of Joanna Lumley and her child, taken in her modelling heyday

Duffy became a contemporary of and good friends with Bailey and Donovan (indeed, Bailey featured and was interviewed in the programme; Donovan didn’t because he sadly passed away in 1996) and, when he eventually went freelance, his studio in the basement of his Swiss Cottage house became a haven of the movers and shakers in the ’60s music, film and art scenes – Duffy’s agent (and later famous film producer) David Puttnam recalled Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and Michael Caine were visitors; it was the likes of these that Duffy frequently rubbed shoulders with. Along with Bailey and Donovan, there’s no question Duffy was an inspiration for the David Hemmings character in Michael Antonioni’s classic 1966 film Blow Up.

An idiosyncratic worker, he liked to play old war songs while shooting models and encouraged them to sing along, as Joanna Lumely (in archive footage from the period) recalled. One day he insisted he wanted to shoot her with her toddler son, so the next day she brought him along to the studio and he did just that. As part of the programme, a somewhat cheesy ‘recreation’ of this session was filmed back in the modern day (although it did effectively display the undeniable affection that still exists between the former shooter and the former model). In fact, this wasn’t set up for the documentary itself, but for a long overdue exhibition of Duffy’s work over the years, which was held in January this year at a London gallery.

Towards the end of his first decade in the business he set up a company, through which he successfully moved away from fashion photography and into more experimental work. When, at the height of the ’70s Glam Rock era, he was approached to produce the artwork for Bowie’s Aladdin Sane album, he was advised to spend as much money as humanly possible on the project, in order to force the record company to take notice how much their outlay for the album was so they’d take it more seriously. He had no qualms and the leading image he came up with for the project surely has to be one of the most instantly recognisable album covers of all time – not least a pretty influential one.

Glam-tastic: Cover art for Bowie’s Aladdin Sane album

There was a disappointing involvement in the filming of the musical Oh! What A Lovely War, for which he only ended up a producer (along with The Iprcess File writer Len Deighton) after instigating the project when he and Bailey watched the original stage version one day and he was blown away by the experience. Unfortunately for him, he was artistically ‘crowded out’ by luvvies; given his Cockney routes, this was the sort of arty crowd he didn’t feel at home with. Richard Attenborough would go on to take plaudits for his work on the film as a debut director. And there was also an unsatisfactory experience in shooting an arty Pirelli calendar in the mid-’70s.

However, Duffy returned to form in a big way, creatively and financially, later in the ’70s with his work on ad campaigns. The biggest success of which was his visually striking, surrealist creations for Benson And Hedges tobacco. So successful was his work, the campaign’s style was effectively borrowed piecemeal for campaigns to come for decades and decades, with its playful mis-sizing of common objects and substitution of specific objects in familiar scenarios with cigarette packets. And, naturally, Duffy produced all his creations without the aid of anything like today’s Photoshop – as was made clear in the programme, he was an artist who liked to solve technical challenges.

But he also feels the idea of photography-as-art is nonsense. Indeed, towards the end of the documentary, he sat looking at a double plug at the bottom of a wall as his exhibition was taking shape around him (he couldn’t attend the opening night owing to health problems) and wryly commented on its artistic merits. To him, it seems, anything can be art if so-called experts declare it to be so – it’s only the art itself, or in his case the images he’s created, that’s the real art; all the chatter around it is crap. He may have a point.

Caged beast: Image from the 1978 ad campaign for Benson And Hedges cigarettes

The programme left you with the feeling that it’s a bit of a pity this great artist (there, I said it) wanted to give the impression he didn’t really think that much of the work he’d created over the course of his career; after all, he seemed rather ambivalent about his exhibition and, when he quit photography altogether at the end of ’70s, he burnt a lot of his negatives in his back garden, at least before (in a very British manner) some dogsbodies from the council turned up and told him to put the fire out. And yet, in spite of this, when talking of his work on the Aladdin Sane album he showed off the original image of the cover with undeniable pride. Unquestionably, then, there’s hypocrisy to the man – just like the decades in which he was active, I guess. In the end, he’s probably most happy talking crap with his old pal David Bailey, like they did back in their heyday – as Bailey said, he usually just sat there while Duffy did all the whining.

In which case, it may be fitting to leave the final words to Duffy himself:

“Before 1960, a fashion photographer was tall, thin and camp. But we three [Bailey, Donovan and Duffy] are different: short, fat and heterosexual”

That may say it all…

For more on Brian Duffy, visit:

http://www.duffyphotographer.com/duffy_website.html

George

Yellow Submarine (1968) ~ Review

Directed by: George Dunning

Starring (the voices of): Paul Angelis, John Clive, Dick Emery, Geoffrey Hughes, Lance Percival, Peter Belton

Screenplay by: Lee Minoff, Al Brodax, Jack Mendelsohn, Erich Segal, Roger McGough

UK/ US; 90 minutes; Colour; Certificate: U

~~~

Yes, it’s the cartoon cornucopia tour de force that is 1968’s Yellow Submarine. You’d quickly suss me out as a bad liar if I tried to convince you I’m not a big fan of The Fabs – and, hot on the heels of that, you’d probably discover this very flick has worked its way into my heart too; in a big way.

And, also in a big way, methinks time hasn’t been kind to this film, unlike the bona fide (ie because they star them) Beatles films A Hard Day’s Night and Help!, this ‘un seems to have faded a bit from mainstream memory. Yes, it’s animated; yes, it features vocal talent doing The Fabs’ voices; and, yes, it doesn’t feature outstanding original songs. But, for me, none of that matters, because Yellow Submarine is a gem; an undeniable sparkling, 24-carat diamond that wouldn’t look out of place mong those floating in the sky alongside Lucy.

Produced in the wake of The Fabs’ uber-famous Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album, this movie takes its inspiration, style and tone very much from this fondly recalled, friendly-hippy Beatles era, rather than from their darker, earthier and rockier White Album era, which, ironically, came in during the year of the film’s release. Take, for instance, the Beatles characters – fun-lovin’ and colourfully dressed, moptoppy, hippy types. Take the story – The Fabs are enlisted by a yellow submarine-driving chap named Fred from the green and pleasant Pepperland to save his home from the meany Blue Meanies. Take the tunes that, ahem, pepper the movie – so many of the mid- to late-’60s faves are here. And take, too, the sublimely glorious animation style so obviously and finely inspired by Peter Blake’s seminal cover art for the Sgt Pepper album.

Actually, one might argue that the best thing about Yellow Submarine is its animation. It works brilliantly alongside the numerous musical interludes; many of which would shame music videos from any era – in particular, the Eleanor Rigby, Nowhere Man and All You Need Is Love sequences are great, great standouts. But, for me, the animation works inherently well with everything else in the film – the wacky, witty script that far more than nods to old Beatles favourite Alice in Wonderland; the voice talents including Dick Emery and Lance Percival; and the childish, innocence, but also drug-informed tone of the whole thing.

Indeed, you could say Yellow Submarine is a cross between a fairly traditional kids’ film and ’60s art-house curiosity. But, if it is then, these two approaches work and blend wonderfully well together in my book. It may be too cute and tries too hard to encapsulate the Fabs for some, it may be way too off-kilter and psychedelic for others (it’s very psychedelic, at times like The Magic Roundabout on acid), but neither of these things bother me – I just enjoyed it too much for them to. So pull up the anchor, down periscope and full-speed ahead to Pepperland, for that’s where it’s at – or I’m a Nowhere Man myself!

George

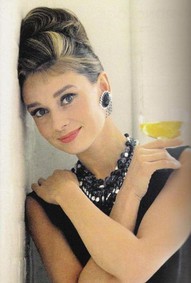

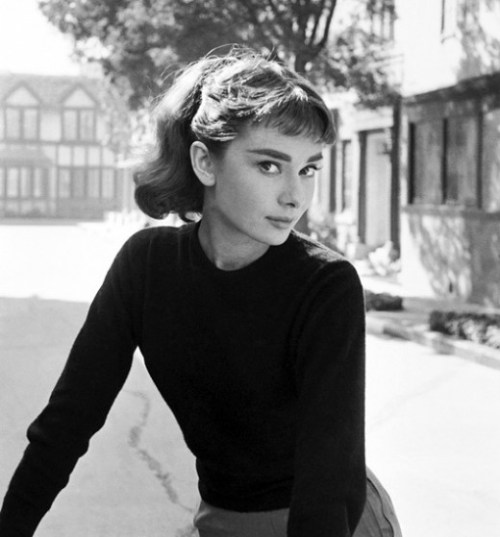

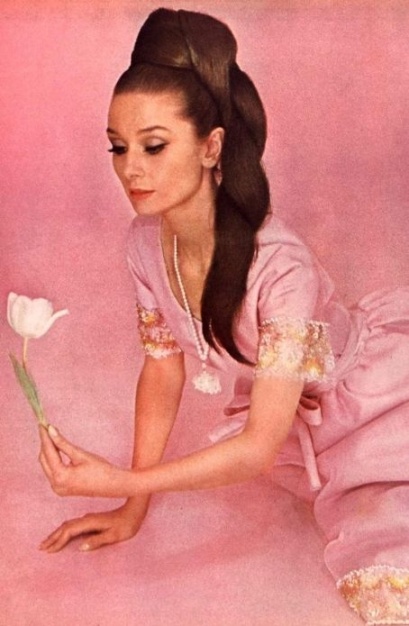

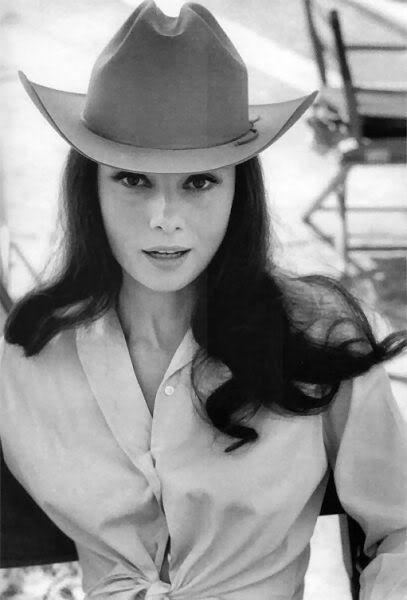

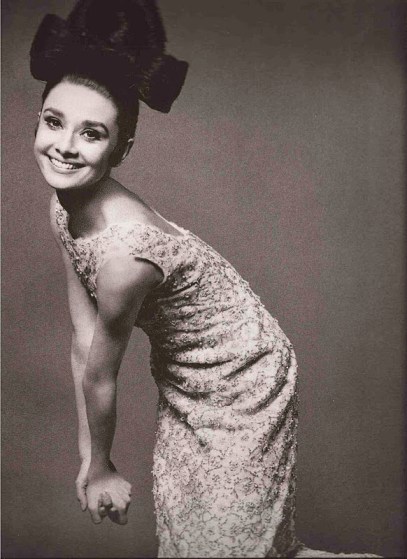

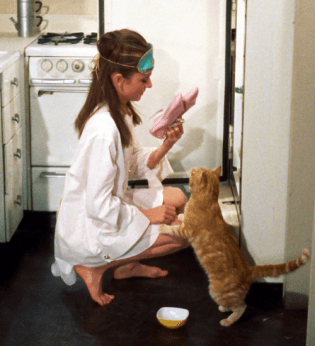

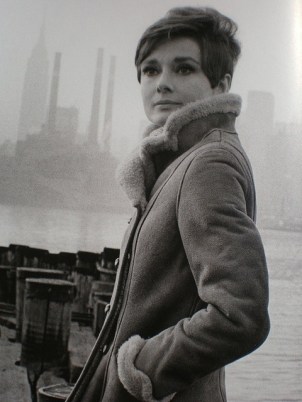

Audrey Hepburn: Angel Delight

.

Talent…

.

… These are the lovely ladies and gorgeous girls of eras gone by whose beauty, ability, electricity and all-round x-appeal deserve celebration and – ahem – salivation here at George’s Journal…

~~~

First up, fittingly, it’s a screen star who’s always been something of a must with me – and I’m certainly not the only one – she’s the epitome of graceful, dignified and delicate beauty, was a comic actress par excellence with buckets full of a pathos and is missed greatly all around the world…

~~~

Profile

Name: Audrey Kathleen Hepburn-Ruston (Edda van Heemstra)

Nationality: Belgian

Profession: Actress/ Humanitarian

Born: May 4 1929, Ixelles, Belgium (Died: January 20 1993, Tolochenaz, Switzerland)

Height: 5ft 7in

Known for: Roles in Roman Holiday (1953), Sabrina (1954), Breakfast At Tiffany’s (1961), Charade (1963), Paris When It Sizzles (1964), My Fair Lady (1964), How To Steal A Million (1966), Two For The Road (1967), Robin And Marian (1976) and Always (1989)/ Work as a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador – 1988-93

Strange but true: She attributed her forever slender figure on the malnourishment she suffered as a child hiding from the Nazis in occupied Holland during the Second World War

Peak of fitness: Playing a small guitar, sitting on a fire-escape and singing Moon River in Breakfast At Tiffany’s

~~~

CLICK on images for full-size

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Coming in – rather than going out – with a bang: Roger Moore makes his debut as Bond in 1973’s Live And Let Die

So, to kick off the ‘Legends’ corner here at George’s Journal, I’ve decided to start as I mean to go on, by taking a look at an undeniable legend of the British small- and large-screen for more than 30 years – and one very close to my heart.

Roger Moore is, it seems, remembered fondly by fans of film and TV. Nowadays most often to be seen in one of his seven James Bond films screened on a public holiday on the box wherever one is in the world, his presence enwraps you as snugly as that new snanklet you just bought off the Net or warms your cockles as pleasingly as a cup of hot cocoa before bed. Back in the day, he was handsome, confident, twinkling-of-eye, witty and with that errant eyebrow; nowadays he’s avuncular, wears tinted glasses, lives in Monaco and Gstaad and promotes the Post Office. As big-time adventure heroes go, you don’t get much more cuddly – or, indeed, merry – than Roger.

But is that doing him a disservice? Is there more to Moore than that? Should we look beyond the persona that seems to be summed up by Q’s delivery of the line ‘I think he’s attempting re-entry, sir’, at the end of Moonraker?

Well, on the one hand, no, probably not; for that’s who he is, and rightly so. But, on the other, I’d say, yes, absolutely. Moore is the embodiment of a ‘legend’ for me, because there’s a wonderful retro nostalgia one can attach to him, but if you scratch the surface, there’s much more depth there to be discovered – and enjoyed.

Sir Rog was born in 1927 in Stockwell, London, to policeman father George Moore and mother Lily. Conscripted in the army for his national service, he rose to the rank of Captain and served in West Germany, performing in the entertainment branch. He worked for an ad agency in London’s Soho and soon was accepted into the esteemed Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA), before treading the boards in small roles in the West End and on the road in repertory theatre. Following this, he turned down a chance to join the esteemed Royal Shakespeare Company, instead deciding to seek fame and fortune on-screen – this may have been the first time the self-proclaimed ‘ponce’ followed the money instead of perceived art. Yes, in all fairness, it wouldn’t be the last.

Moore quickly found himself in the States, eeking out a decent living as a contract player with MGM. However, it didn’t lead to much in the way of roles or exposure, so in the late ’50s he drifted into US television, initially fronting drama Ivanhoe, loosely based on the Walter Scott novel of the same name, and then appearing opposite James Garner (a very similar actor – almost an American version of Moore, to my mind) in Maverick, the original series on which the 1994 Mel Gibson film was based. He eventually took lead duties on that series too once Garner moved on.

Knock-out: Tony and Rog hit the heights in The Persuaders!

Shortly after this, Sir Rog moved back to the UK and in 1960 was cast as the roguishly heroic Simon Templer in The Saint, a series based on Leslie Charteris’s novels and produced by Lew Grade for ITC/ ATV. In actual fact, Moore had looked into acquiring the rights to The Saint several years before. It was this role that rocketed him to relative stardom – he starred in 118 episodes; making up six series, three of them in colour, long before colour TV sets were available to the great unwashed in Britain. But then, The Saint was a series with lofty ambitions, all of which it fulfilled.

Made as much for the American market as for that of the homegrown UK, it was very much a part of television’s mid- to late-’60s spy-detective genre that was influenced by and riding on the wave of 007’s popularity at the cinema, but which at the same time carved out a nice cultural niche for itself. Contemporaries of the series included The Avengers and The Prisoner. Aside from Moore himself, the series is surely most memorable for the halo that would appear above his head whenever he or someone else would identify him as The Saint/ Simon Templar in the pre-title opening scene, and for the sprightly, kooky Edwin Astley tune over the titles, as well as the white Volvo 1800 Templar drove in practically every episode.

Unfortunately, actors and crew on The Saint weren’t allowed to venture to any of the foreign locales where the episodes were set, filming being limited to Elstree Film Studios and the surounding countryside instead – not that that bothered Moore; he always liked to return home to his wife and kids after a long day’s shooting. However, with a bigger budget on his next project, The Persuaders!, this time Sir Rog was forced to film abroad. Indeed, the budget on this 1971 series was so much larger it managed to secure Hollywood actor Tony Curtis’s services as co-star.

Of the two, I prefer The Persuaders! to The Saint. Yes, its production values are higher, but the real seductive thing about it is the repartee between Curtis and Moore as, respectively, New York millionaire Danny Wilde and English aristocrat Lord Brett Sinclair. Together, they’re a joy to behold. Our two heroes, playboys with limitless funds and inexhaustible wardrobes, gallivant all over Europe on colourful, crime-addled adventures, while villains with dodgy ‘foreign’ accents fruitlessly attempt to stay one step ahead – or, depending on the situation, behind – them. The one down-side to The Persuaders! is that it didn’t make the grade in the US, ensuring sadly only one series was made. However, if it had been a success Stateside we would probably never have seen…

Suits you, sir: He may be wearing a safari suit, but look who’s surrounded by a gaggle of girls in 1979’s Moonraker

… Sir Rog cast as James Bond. This happened following Sean Connery’s second departure from Eon Productions’ extraordinarily endurable film series, following the latter’s final fling in Diamonds Are Forever. Moore had been considered by producers Albert R ‘Cubby’ Broccoli and Harry Saltzman for the part of Britain’s most famous secret agent way back in 1962 when Connery was first cast, but his commitment to The Saint precluded him. So, in 1973, at a youthful-looking 46, Moore made his bow as Bond in Live And Let Die, an intriguingly Blaxpoitation-informed addition to the Bond canon that brought the series slap-bang into the funktastic Seventies. It was a success – actually, Live And Let Die remains the fifth most successful Bond film at the worldwide box-office, inflation adjusted, just ahead of Daniel Craig’s Casino Royale. Six more Eon-produced Bond films followed for Roger; The Man With The Golden Gun (1974), The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), Moonraker (1979), For Your Eyes Only (1981), Octopussy (1983) and, finally, A View To A Kill (1985).

Now, if I‘m being honest, it’s perhaps when one delves a little deeper into Moore as Bond that one can really find there’s more to his contribution to popular culture than meets the eye. Looking closely, it becomes apparent that throughout his 12 years in the role, he was asked to play the character in subtly different ways – almost from film-to-film. His Bond hops from a romantic-cum-foolish hero (LALD) to a harder incarnation (TMWTGG) to a smooth Cary Grant type (Spy and MR) to an ageing civil servant (FYEO) and, finally, to a nearly-over-the-hill government assassin (OP and AVTAK). While Moore wasn’t fond of the violent side of the character, and has an aversion to real-life guns, if you look close enough you’ll discover a hard edge, a ruthlessness and an earnestness uncover themselves in his 007 . In short, there was certainly more to his version(s) of Bond than a smutty line delivered tongue-in-cheek and a cocked eyebrow. Although, God love him, there was plenty of room for that too.

Following his agreement with Cubby Broccoli he should hang up the shoulder holster in the mid-’80s, he found himself rather devoid of good acting projects. There had been many while he was Bond – Gold (1974), Shout At The Devil (1976), The Wild Geese (1978), Escape To Athena (1979), North Sea Hijack (1979), The Sea Devils (1980) and The Cannonball Run (1981) – all of them frolicsome adventure hokum perhaps, but good fun and solid hits in which Moore shared the screen, collectively, with the likes of Gregory Peck, Richard Burton, David Niven, Richard Harris, Telly Savalas, Hardy Kruger and Lee Marvin. But now, at the age of 58 and, admittedly, looking it, good work looked harder to come by; perhaps even more so when he realised he’d made a mistake and pulled out of the original production of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1987 stage musical Aspects Of Love just before curtain-up of the dress rehearsal.

However, it wasn’t long before Sir Rog found for himself another – probably higher – calling. Roped into attending a UNICEF event by his old friend and neighbour in Switzerland, the glorious Audrey Hepburn, this led to him being offered the chance to carry on her great work for the organisation by becoming a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, upon her untimely death in 1993. Over the course of nearly the last 20 years, this has seen him genuinely work tirelessly, travelling all over the world to downtrodden locales, as well as pressing the flesh with politicians and businessmen and raising as much publicity for UNICEF’s work as he’s been capable of. That says a lot for the man who has always maintained he’s a real ‘ponce’, methinks.

Then… and now: At a UNICEF event – is that a royal wave from Sir Rog?

So, while it’s easy to dismiss Sir Rog as the ‘second – or even third or fourth – best Bond’, or the easy-going 007 who never really acted in the role, methinks the feller deserves more credit for his position in the popular culture firmament. He can act, you just need to look out for it – indeed, if you never have, check out the 1970 thriller The Man Who Haunted Himself, in which Moore plays two roles: the haunted man of the title and dark doppelganger that haunts him. There’s no scrimping on the acting front from Rog in that one.

What’s more, he was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2007 (appropriately located at 7007 Hollywood Boulevard) and was knighted in 2003 for his charity work. Now, they don’t hand either of them out to just anyone. So here’s raising a glass – a vodka Martin, shaken and stirred – to the thrice-married bon viveur extraordinaire, good friend of both Connery and Caine and exponent of a suave, bawdy and irresistible manner that one can try to emulate, but will probably never get anywhere near to… the toast then is Sir Rog, a legend, who at 82 not-out, is far from toast.

George