Playlist: Listen, my friends ~ March 2012

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or have never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and enjoy…

.

CLICK on the song titles to hear them

.

The Dave Brubek Quartet ~ Blue Rondo À La Turk

Manfred Mann ~ 5-4-3-2-11

Erroll Garner ~ On The Street Where You Live/ I Could Have Danced All Night2

Judy Collins ~ In My Life

Marvin Gaye ~ Abraham, Martin And John

Leon Russell ~ Jumpin’ Jack Flash/ Young Blood3

Uriah Heep ~ Look At Yourself

The Hues Corporation ~ Rock The Boat

Sarah Vaughan ~ Fool On The Hill

Rondò Veneziano ~ La Serenissima4

The Pretenders ~ I Go To Sleep5

Mike Post ~ Theme from L.A. Law

The Adventures ~ Broken Land

.

1 Written for and featured over the opening titles of ITV’s ‘Beat music’-driven early Friday evening show Ready Steady Go! (1963-66)

2 Originally from the stage and film versions of the Lerner and Loewe musical My Fair Lady

3 From the George Harrison-organised Concert For Bangladesh (1971) – accompanying Russell on stage here are performers Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Billy Preston, Ringo Starr and Harrison himself

4 The Baroque-costumed chamber orchestra’s classic pop-cum-classical hit, which headlined the Venice In Peril album, itself a driving force behind the campaign to prevent the sinking of Venice in the 1980s

5 The even-better-than-the-original cover of The Kinks’ song from their second album Kinda Kinks (1965)

Muppet Mania: Felt perfection? ~ The Muppets (2011)/ Review

Directed by: James Bobin

Starring: Jason Segel, Amy Adams, Chris Cooper, Rashida Jones, Jack Black, Emily Blunt, Alan Arkin, Kristen Schaal, Jim Parsons and, of course, The Muppets

Screenplay by: Jason Segel and Nicholas Stoller

US; 103 minutes; Colour; Certificate: U

.

What better way to spend a cold, wintry Monday night, thought I a few evenings ago, than rolling up at the Empire Leicester Square and, once ensconced inside, watching the latest Muppet movie? What better way to spend it, indeed, you may ask. But is there? Did I find the latest Muppet movie better than, equal to or even a fitting endeavour after the first, classic Muppet movie, er, The Muppet Movie (1979)? Is it felt perfection or did it, in fact, make my fur fly?

We’ve certainly had to wait a while for a proper, fully-blown, cinema-released Muppet flick – 12 years, to be exact, given the last was the unquestionably underwhelming Muppets In Space. And, as revealed in the first of my ‘Muppet Mania’ posts here, under the Disney umbrella our favourite furry friends have been a little lost of late (arguably their biggest success has come in an Internet music video parody). To say it must have been a big challenge then for a new generation of filmmakers (and die-hard Muppet fans) spearheaded by How I Met Your Mother star Jason Segel to bring ’em back to flickatoriums in an adventure that doesn’t just make moolah, but also does them justice, is an understatement the size of Sweetums. Yet, in this final ‘Muppet Mania’ post, I can happily declare that, for the most part, they’ve pulled it off – and that’s probably most of all down to the fact they are, like so many out there, such big enthusiasts of Kermit and co.

Indeed, surely anyone’d realise The Muppets (as the movie’s not so imaginatively titled) is made by fans. All the way from its mock-sentimental but endearing opening montage to its ebullient, genuinely uplifting song-and-dance finale, it’s a nostalgia-fest harking back to the days when Jim Henson’s heroes straddled the starry showbiz firmament like fuzzy demi-gods, belittling household names in their infamous Muppet theatre for a half-hour each week on TV sets across the globe.

It’s this cartoonish, cosy but wonderfully irreverent fantasy world that The Muppets seeks to recreate; its brain-free-as-Beauregard plot revolving around the trip to Hollywood taken by Muppet fan-of-old Gary (Segel), his girlfriend Mary (Adams) and Muppet-obsessed brother Walter (who seems actually to be a Muppet), ostensibly for the former couple’s 10-year anniversary, but just as much for Walter to make pilgrimage to the now run-down Muppet Theatre. There, the latter discovers a heinous scheme by evil oilman Tex Richman (Cooper) to buy the theatre – and the Muppets brand with it – and knock the building down for greedy business interests. Of course, Walter believes there’s only person who could possibly prevent this catastrophe: yes, Kermit. And, once the legendary amphibian is sought out, he himself can only think of one solution: getting the Muppets back together and putting on a one-off Muppet Show-cum-telethon to save their former home – and themselves.

In dedicating its first act to bringing the big-time troupe members back together one-by-one (and amusingly so too: Fozzie’s now in a crap Reno Muppet-tribute act called The Moopets; Gonzo runs a toilet empire and Animal’s entrenched in anger management therapy), the story smartly and effectively echoes that of the original Muppet Movie, which, of course, told the tale of how they all came together in the first place. Aside from fourth-wall-breaking moments (again reminiscent of The Muppet Movie), such as the gang saving time on car trips by travelling ‘by map’ rather than by road, generally though this flick most references – and, in a way, arguably tries to recreate – The Muppet Show.

As such, its second act is a Muppet twist on the old showbiz ‘let’s put on a show’ tale, including the gang doing up their theatre to the tune of Starship’s We Built This City (Segel and friends are clearly fans of ’80s corn as well as all-things Henson) and its third act is the actual telethon itself, featuring utterly familiar acts delivered by Fozzie, Gonzo, Animal and the rest of The Electric Mayhem band, while Kermit and Scooter try to keep control of the totally pants, but rather wonderful production.

The sub-plots of Kermit and Miss Piggy’s and humans Gary and Mary’s mirroring relationship troubles are mixed in too (the former maybe more successfully than the latter, given this is a Muppet movie and the former sub-plot, well, involves actual Muppets), but there’s also Walter’s realisation as a Muppet himself – the Disney-esque discover-and-be-yourself/ the-best-you-can-be character arc – which is nicely done and gives rise to the flick’s best tune, the utterly Oscar-win-deserving and barmily brilliant Man Or Muppet (see below), written like all the others by Flight Of The Conchords‘ Bret McKenzie.

And talking of humans, one should perhaps note their efforts. Aside from Segel, who’s clearly loving every moment and makes for a more than adequate lead and foil to the felt players, Amy Adams hoofs and sings like a good ‘un – not surprising given her turn in Disney’s Enchanted (2007) and pre-Hollywood background in cabaret – while Rashida Jones provides effective support and both Emily Blunt and The Big Bang Theory‘s Jim Parsons give memorable cameos. Chris Cooper’s antagonist may feel like he belongs in a different movie (something aimed at under fives), but then he’s about the only thing that does.

For The Muppets certainly knows what it is, all right – a sort of updating of both The Muppet Show and The Muppet Movie for a generation of youngsters who weren’t even a figment of their parents’ imagination when the Muppets were in their prime, while at the same time an earnestly affectionate and knowing tribute to the Muppets in their prime for their parents. Co-scripted by Segel and Stoller – the former wrote and starred in Forgetting Sarah Marshall (2008) and the latter directed both that and its ‘sequel’ Get Him To The Greek (2010) – and directed by Bobin (who helped create the characters of Ali G and Brüno and with McKenzie co-created Flight Of The Conchords) it certainly is knowing, has more edge to it and is sadder in moments than any Henson-era Muppets venture was (rather like, say, last year’s Toy Story 3). But then, this is the 21st Century and, as the flick points out, it’s a world that’s moved on from the era that the Muppets took by storm.

Does it, though, prove there’s still a place in today’s cynical world for them, nay, that the world still needs them? Well, let’s just say that on that cold, wintry Monday night I saw The Muppets, I was sat next to a middle-aged chap on one side and a little boy on the other and based on their clear enjoyment of the anarchic antics they viewed on the big screen before them, they both certainly seemed to think so. Altogether now: “Mah-Nà-Mah-Nà…”

.

Muppet Mania: 25 things you always wanted to know about Labyrinth, but were afraid to ask Jareth

It’s only forever: a quarter of a century after its original release, Jim Henson’s family film spectacular Labyrinth has never been more popular – not least because of star David Bowie

So, yes, the third of this blog’s four ‘Muppet Mania’ posts is, indeed, an unadulterated celebration of the awesome Labyrinth (1986). An unforgettable blend of fairytale, Alice In Wonderland and The Wizard Of Oz with Muppet-like characters, off-kilter humour and – oh yes – David Bowie, it’s maybe not the greatest family fantasy flick ever made, but one of the most beloved to have come out of the ’80s.

Indeed, although we’ve just seen a new Muppets movie released, it’s pretty unthinkable we’ll see a movie quite like Labyrinth again – what with its sense of very ’80s Lucas-like/ Spielbergian fantasy wonder, amazing creatures and sets you feel you can touch as they were manufactured in a workshop not a computer and, of course, Bowie’s extraordinary wig and lunchbox. Certainly, it deserves its unique place in pop culture history and is always worthy of a (magic) dance whenever it’s popped into the old DVD player. Anyhoo, enough of this chit-chat, we only have 13 hours to reach Goblin City, after all…

.

1. During a limousine ride following a screening of The Dark Crystal (1982), the $40 million-grossing fantasy adventure they made together, British artist Brian Froud and creator of The Muppets and US director Jim Henson came up with the idea of another cinematic collaboration based around the traditional idea of goblins snatching a baby – Froud soon worked up an image of this concept (see below).

2. Henson later stated that at that time he and Froud “wanted to do a lighter-weight picture, with more of a sense of comedy since The Dark Crystal got kind of heavy – heavier than we had intended. Now I wanted to do a film with the characters having more personality and interacting more”.

3. He approached Monty Python And The Flying Circus member Terry Jones to write a screenplay based on his daughter’s recommendation, as she had just read Jones’s children’s book The Saga Of Erik The Viking (1983), which itself was later adapted as a movie by Jones.

4. Although Terry Jones is Labyrinth‘s only credited writer, the shooting script actually also contained contributions from Henson, screenwriters Laura Phillips and Elaine May and executive producer George Lucas (who also helped Henson edit the finished film). The screenplay went through 25 drafts between 1983 and ’85 – mostly to inject songs and more humour to ensure legendary pop star David Bowie would agree to star as antagonist Jareth the Goblin King.

Top artwork and pop artist: Brian Froud’s first concept art for Labyrinth, a baby surrounded by goblins who’ve kidnapped him; Lucas and Henson with their choice for Jareth, David Bowie

5. Jones has said of the eventual film: “I didn’t feel that it was very much mine. I always felt it fell between two stories; Jim wanted it to be one thing and I wanted it to be about something else”. Jones’s original script was darker and had more of a focus on Jareth’s vulnerability.

6. Originally, Jareth was conceived as a puppet-based creation until Henson decided that the movie’s two main characters ought to be played by actors. He considered casting a magician for the part, as well as Sting or Michael Jackson, before pursuing Bowie as the latter “embodies a certain maturity, with his sexuality, his disturbing aspect, all sorts of things that characterise the adult world”.

7. For his part, Bowie’s said on accepting the role: “I’d always wanted to be involved in the music-writing aspect of a movie that would appeal to children of all ages, as well as everyone else, and I must say that Jim gave me a completely free hand with it. The script itself was terribly amusing without being vicious or spiteful or bloody, and it had a lot more heart in it than many other special effects movies. So I was pretty hooked from the beginning”.

8. During development, the film’s protagonist varied from a king to a Victorian girl, via a fantasy-world princess, until a modern teenager named Sarah was decided on. After British actress Helena Bonham-Carter auditioned for the role, the character’s nationality was chosen as American – probably for US marketing purposes.

Three of a kind: Sarah’s Oz-like companions Hoggle (l), Ludo (m) and Sir Didymus (r)

9. Hollywood stars-to-be Sarah Jessica Parker, Marisa Tomei, Mia Sara, Yasmine Bleeth, Ally Sheedy, Laura Dern and Jane Krakowski were all considered for Sarah before 14 year-old Once Upon A Time In America (1984) actress Jennifer Connelly was cast. According to Henson, as was critical for the role, she “could act that kind of dawn-twilight time between childhood and womanhood”.

10. Labyrinth‘s plot sees Sarah trying to recover her kidnapped baby brother Toby (played by Brian Froud’s son, also called Toby) from Jareth and his horde of goblins. It incorporates elements clearly inspired by Alice In Wonderland (Sarah finds herself in a peculiar and magical fantasy world inhabited by weird and wonderful creatures) and The Wizard Of Oz (she must undertake a challenging journey – not along a road, but through the labyrinth of the film’s title – with three good-hearted companions to reach the land’s leader where her adventure will conclude).

11. The movie’s climax takes place in a room in Jareth’s castle that features gravity-defying staircases heavily influenced by MC Escher’s 1953 lithograph Relativity (see top image).

12. Shooting on Labyrinth began at Elstree Studios, Hertfordshire, England on April 15 1985 and principal photography wrapped about four months later on September 8. Exterior shots were captured at West Wycombe Park, Buckinghamshire (the film’s opening) and the New York State towns North Nyack, Piermont and Haverstraw (all used for the following sequence when Sarah runs home).

.

13. The puppet-operating and voice-acting team that worked with Henson on Labyrinth was drawn from those he’d collaborated with on The Muppet Show (1976-81) and previous Muppet movies, his children’s show Fraggle Rock (1983-87), revolutionary kids’ educational programme Sesame Street (1969-present) and one came from classic satirical effort Spitting Image (1984-96). They included Frank Oz (famed as operator and voice of Star Wars‘ Yoda and later a director himself), Dave Goelz, Ron Mueck, Kevin Clash, Karen Prell, Rob Mills, Anthony Asbury and Henson’s own daughter Cheryl and son Brian (who later directed Muppet movies in the 1990s).

14. Each of the major puppet characters (Hoggle, Ludo, Sir Didymus, Ambrosius – who in some shots was a real dog – and the five Fieries) were designed and made by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop and required a team to operate them. The most complicated was Hoggle, who has the most screen-time and boasts a genuine character arc. A dwarf actor wore his costume, while Brian Henson and three further operators radio-controlled his animatronic head. Henson explains: “five performers trying to get one character out of one puppet was a very tough thing; basically what it takes is a lot of rehearsing and getting to know each other”.

15. Labyrinth was an ambitious project in terms of set design. The Goblin City set was built in Stage 6 of Thorn EMI Elstree Studios, London, and featured cinema’s largest ever panoramic back-cloth. The forest Sarah and her companions pass through to reach the castle required 120 truckloads of tree branches, 1,200 turfs of grass, 850 pounds of dried leaves, 133 bags of lichen and 35 bundles of mossy old man’s beard (usnea). Meanwhile, the Shaft Of Hands sequence was filmed on a 40-feet-high rig and involved nearly a hundred performers’ hands.

16. Cheryl ‘Gates’ McFadden, who would go on to become a sci-fi icon as Dr Beverly Crusher in Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94) and its follow-up films, worked on Labyrinth as a choreographer. She did the same on previous Henson movies The Dark Crystal and The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984).

Jim who fixed it: Henson directing Hoggle (l), posing with the latter and puppet co-stars Ludo, Sir Didymus and Ambrosius (m) and telling human actress Jennifer Connelly what’s what (r)

17. David Bowie recorded four songs for the film’s soundtrack: Underground, Magic Dance, As The World Falls Down and Within You (all of which he ‘performs’ in the movie). The first two were released as singles – Underground reached #21 on the UK charts (see its video in bottom clip). The film’s score was written by British composer Trevor Jones.

18. The film’s other song Chilly Down was written by Bowie, who recorded a version that didn’t appear in the movie. Instead, it is performed on-screen by the Fieries, one of whose voices belonged to actor Danny John-Jules who would go on to play Cat in sci-fi sit-com Red Dwarf (1988-present) and appear in kids’ show Maid Marian And Her Merry Men (1988-94), for which he also performed the memorable theme tune.

19. Merchandise produced to promote the movie included plush toys of both Sir Didymus and Ludo, a board game, a computer game, comic books and jigsaw puzzles. The film’s characters and sets also toured US shopping malls in cities including New York, Chicago and Dallas.

20. Labyrinth received its US theatrical premiere on June 27 1986 and opened in the UK on November 28. It was selected for the prestigious UK Royal Premiere of 1986, which took place on December 1 and was attended by Prince Charles and Princess Diana, ensuring it enjoyed significant coverage in the British media. An hour-long behind-the-scenes documentary Inside The Labyrinth was also broadcast on TV.

Manga, magazines and gamers’ delight: the four-part Return To Labyrinth comic book series (2006-10) (l), Kermit and Jennifer Connelly on the cover of the summer ’86 issue of Muppet Magazine (m) and Activision’s Labyrinth: The Computer Game released in 1986 (r)

21. Labyrinth posted disappointing figures in cinemas. It opened at #8 at the US box-office behind, among others, The Karate Kid Part II, Top Gun and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (all 1986). With a budget of around $25 million, it grossed only $12.8 million; it achieved just 66th place on 1986’s US box-office list.

22. The movie also received a mixed response from the critics. Roger Ebert gave it two out of four stars, claiming “it never really comes alive”, but Nina Darton compared it favourably to ETA Hoffman’s classic tale The Nutcracker And The Mouse King (1816), the basis for Tchaikovsky’s ballet: “(The Nutcracker) is also about the voyage to womanhood, including the hint of sexual awakening, which Sarah experiences too in the presence of a goblin king.”

23. Unquestionably, however, as the years have passed, it has achieved huge cult – if not mainstream – popularity with repeat TV screenings and high VHS and DVD sales; young fans seemingly love it as a classic family fantasy adventure, while those who remember it from its original release look on it as a slice of ’80s nostalgia. Since 1997, the Labyrinth Of Jareth, a two-day masquerade ball, has been held by die-hard fans in Hollywood.

24. In 2006, the manga-lite publisher Tokyopop began producing a four-part series of popular comic books entitled Return To Labyrinth, whose plot involved a teenaged Toby returning to Jareth’s world, while in 2010 director Dave McKean and author Neil Gaiman collaborated on the film MirrorMask, which initially had been intended as a prequel to Labyrinth entitled Curse Of The Goblin King.

And finally:

25. Although the financial failure of Labyrinth sent Jim Henson into a flunk, according to his son Brian, before his death in 1990 “he was able to see all that [growing popularity of Labyrinth] and know that it was appreciated”. David Bowie has also commented: “every Christmas a new flock of children comes up to me and says, ‘Oh! you’re the one who’s in Labyrinth!“, while Jennifer Connelly has said: “I still get recognized for Labyrinth by little girls in the weirdest places. I can’t believe they still recognize me from that movie. It’s on TV all the time and I guess I pretty much look the same”.

.

Further reading:

http://www.astrolog.org/labyrnth/movie.htm

.

Muppet Mania: Miss Piggy ~ Diva Forever

Talent…

.

… These are the lovely ladies and gorgeous girls of eras gone by whose beauty, ability, electricity and all-round x-appeal deserve celebration and – ahem – salivation here at George’s Journal…

~~~

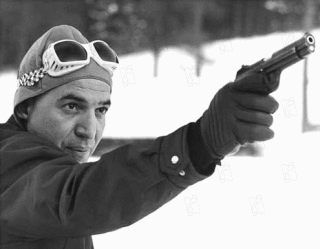

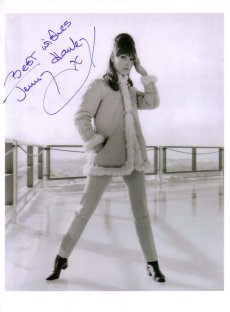

The second of this month’s four ‘Muppet Mania’ posts is a celebration of the stand-out star among our felt-tastic heroes – or at least she believes she’s the stand-out star. She’s hardly shy and retiring (she’ll stick her snout in whether it’s wanted or not), but she is – like every other Muppet – utterly lovable. And many’s the celebrity who’s found her (ahem) a sexy slab of meat – and that’s far from telling a porky. Yes, peeps, the latest entry in this blog’s Talent corner is the inimitable, irrepressible, immaculate Miss Piggy…

~~~

Profile

Name: Miss Piggy (real name possibly ‘Miss Piganthia Lee’)

Breed: Pig

Nationality: American

Profession: Porcine superstar

Background: In a 1979 New York Times interview, Miss Piggy’s associate Frank Oz said of her: “She grew up in a small town in Iowa; her father died when she was young, and her mother wasn’t that nice to her. She had to enter beauty contests to survive, as many single women do. She has a lot of vulnerability which she has to hide because of her need to be a superstar.”

Height: Taller than Kermit

Known for: Appearing alongside her furry friends – and many a dashing human guest-star – in TV’s The Muppet Show (1976-81) and then in big-screen adventures The Muppet Movie (1979), The Great Muppet Caper (1981), The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984), The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992), Muppet Treasure Island (1996), Muppets In Space (1999) and The Muppets (2011). Her appeal should be an acquired taste – she’s, well, a pig and can be angrier than a horde of wasps caught in a jam-less jam-jar, is a dab-hand at judo and has an ego the size of The Muppet Theatre – but millions around the globe fell in love with her and still do. As does Muppet-leader Kermit The Frog, whose feelings Piggy most assuredly reciprocates – often in public.

Strange but true: Thirty years ago she wrote a self-help book, Miss Piggy’s Guide To Life, which clocked up a mightily impressive 29 weeks on The New York Times Bestseller List, reaching a high of #4 as it did so.

Peak of fitness: Er, maybe only Kermit should answer that question…

.

CLICK on images for full-size

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Muppet Mania/ Legends: The Muppets

It’s mean bein’ green: for over 30 years the famous five (Kermit, Piggy, Fozzie, Gonzo and Animal) and their friends have been entertaining kids and adults alike with anarchic abandon

Some of them are furry, others fuzzy; many of them appear to be animals, others look like humans; most of them are nutty, others (a little bit) more sensible; all of them, though – all of them – are unforgettable and utterly brilliant. They are The Muppets. And, for all the reasons listed above (as if they actually needed listing) as well as because their brand spanking new film opens in the UK this month, they are the latest, unquestionably deserving inductees into the ‘Legends‘ corner of this blog – quite frankly, it’s a mystery how it’s remained a Muppet-free zone for this long (indeed, I can reveal Gonzo’s tried to fire himself out of a cannon and into it before now; but then, well, he is Gonzo).

In fact, owing to their awesomeness, The Muppets will also be the focus of the next three posts of this blog, as ‘Muppet Mania’ verily infects this little nook of the ‘Net. There’ll be a piece on the cult favourite flick Labyrinth (1986), a review of the aforementioned new Muppets movie and, yes, a ‘Talent‘ post as well (no, really). But before all that, in this post let me detail just why our favourite felt friends are so damn legendary.

As with many Muppet stories, this one begins with Kermit. Short, gangly, green but very affable (a bit like a cross between Mickey Mouse and the most amiable chat show host imaginable), Kermit The Frog was the first Muppet to make contact with the human world – and the first to appear on television. This rather monumental event took place in May 1955 on the show Sam And Friends (1955-61), broadcast on the NBC-owned local Washington DC station WRC-TV. Sam And Friends was the brainchild of Kermit’s (and the other Muppets’) closest human friend and collaborator, the one, the only Jim Henson.

Unlike Kermit (who, in a recent interview claimed he was born in a swamp with 3,265 tadpole siblings), Henson was born in Greenville, Mississippi in 1936 and, in the late 1940s, moved with his family to Hyattsville, Maryland, near Washington DC. It was here, while in high school, he began working in television and created puppet characters for a local station’s Saturday morning kids’ programme The Junior Morning Show. On leaving school, he enrolled at the University of Maryland and in his freshman year was approached to create Sam And Friends.

TV takeover: Big Bird and familiar friends in Sesame Street (left), Kermit debuts in Sam And Friends (middle) and the latter fronts an iconic cast of characters in The Muppet Show (right)

The show went out daily and comprised five minute-long episodes of sketches and skits; some of them pastiche, others more counter-culture-esque existential (see first video clip below). It featured several characters, including both the titular and human-looking Sam and, of course, Kermit (whose appearance and voice was unmistakeably that of the later Kermit, even if he was yet to inform viewers he was definitely a frog).

In the ’60s Kermit took something of a back-seat and allowed other Muppets to come to the fore. Several appeared in TV commercials and, accompanying Henson, others guested on talkshows. The culmination of this were the several appearances between ’63 and ’66 of the jazz piano-playing, laid-back dog Rowlf on The Jimmy Dean Show (1957-75). Like Kermit, Rowlf had already appeared on the box (in Purina Dog Chow commercials), but his guesting alongside country star Dean, which practically propelled him to sidekick status on the latter’s variety show, ensured Rowlf became the first recognisable Muppet on US network television.

By 1963, Henson, along with his wife Jane and his growing young family, had moved to New York and formed an entertainment company he entitled Muppets Inc. (the name Muppet perhaps deriving from a combination of the words ‘marionette’ and ‘puppet’). Around this time too, Henson began working with writer Jerry Juhl and Frank Oz; his friendship and collaboration with the latter would last the next 27 years. As the ’60s progressed, the trio drifted towards producing Muppet-featuring experimental films, one of which, Time Piece (1965), was nominated for a Best Short Film Oscar. And at the end of the decade their hard work began to pay off when they started work on a project that resulted in their Muppet friends finding their first – and an unquestionably iconic – home on television. The project was a learning-driven show for young children that would become Sesame Street.

Conceived by the non-profit organisation Children’s Television Workshop (now Sesame Workshop) and broadcast by the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), Sesame Street (1969-present) combined scenes shot on a realistic looking urban set (‘Sesame Street’) starring both human and Muppet characters with film and animation inserts, many focusing on counting and learning the alphabet. The style, colour and vibrancy of the show was revolutionary, ensuring it was an immediate public and critical hit – today it’s considered one of the greatest and most important children’s TV shows of all-time; by 2008 an estimated 77 million people in the US had watched it (and countless more around the world), while by 2009 it had won a staggering 118 Emmy awards.

.

Unquestionably, the most memorable members of Sesame Street’s Muppet cast – Bert and Ernie, Big Bird, Oscar The Grouch, Cookie Monster, Count von Count, Aloysius Snuffleupagus and, of course, Elmo – have become fixtures of the cultural firmament. And owing to its success and their role in that, they can also lay claim to being the first Muppets truly to capture widespread public imagination. Well, that is if they don’t mind admitting they share that honour with, yes, Kermit. For right from the show’s off, in his role as its ‘roving reporter’, Kermit was just as much a part of Sesame Street as any other Muppet. Indeed, it was in this role he defined his on-screen identity for forever after as the sensible if ironic Muppet at the centre of chaos; the one with which human viewers could perhaps most identify. In short, he was the calm at the centre of the Muppet storm.

The real Muppet storm was still a little way off yet, though. It was precipitated by Henson’s decision to widen the appeal of his Muppet pals beyond Sesame Street viewers to more of an adult, or at least family, audience. His first major step in doing so was in securing them among the cast of rising comedians on the opening season of the now legendary Saturday Night Live (1975-present) . Although an instant, game-changing hit, the NBC sketch show didn’t prove the perfect platform for Henson’s furry charges, not least because the show’s writers seemed to find it much easier to write for humans, thus they didn’t return for its second season. However, if SNL didn’t need the Muppets to flourish, very soon the Muppets proved they didn’t need SNL to flourish. For just one year later, yes, The Muppet Show (1976-81) finally arrived on our screens (see video clip below).

Henson had been wanting to get a Muppet-only variety show on prime-time network TV even before flirting with SNL, having produced two pilots in ’74 and ’75 respectively. However, the project really got off the ground thanks to a loosening in US TV syndication rules. He struck a deal with all-powerful UK telly mogul Lord Lew Grade to make a Muppet-centric show with the latter’s ATV Productions, which would be broadcast first on ITV; after which it would be sold to US networks and so could be very quickly shown in syndication. This meant that Henson and the Muppets crossed the channel and set up home at Elstree, just outside of London, ensuring The Muppet Show could be said to be as British as it was American. Well, the money behind it was British, at least.

The show was, of course, a vaudeville-style variety showcase set in a theatre loaned to the Muppets (given its filming in the UK, does this mean their famed theatre is actually located somewhere over here?). Yet, unlike the old song-and-dance shows it resembled, it also gave viewers peeks behind the scenes, most often in the theatre’s wings, as well as at certain audience members who tended not to be very positive about what they were witnessing (yes, Statler and Waldorf, I mean you). But it’d take a heavy-hearted soul who wasn’t entertained by The Muppet Show.

Cycles, crystals and Dickens: Kermit and Piggy ride to box-office success in The Great Muppet Caper (l), cult fantasy The Dark Crystal (m) and Gonzo narrates The Muppet Christmas Carol (r)

In allowing the outrageous slapstick-fuelled antics and almost always absurdist pursuits of the Muppets free rein, Henson’s half-hour shows didn’t just aspire to the variety efforts of old, but also knowingly and pleasingly subverted them and other instantly recognisable TV genres – in fact, nothing was safe from being, ahem, Muppet-ified. Take the near-insane blue dynamo Gonzo The Great’s efforts to push entertainment to ever more explosive highs; Fozzie Bear’s stand-up sets in which his jokes are always dreadfully received; the news flash in which The Muppet Newsman describes a disaster or unsavoury event that then immediately befalls him; the cooking show parody featuring the delightfully deluded Swedish Chef; the Star Trek take-off that was Pigs In Space with its star Link Hogthrob; the General Hospital soap opera parody that was the Rowlf-as-a-doctor-featuring Veterinarian’s Hospital; or the constant confounding of prudish Sam The Eagle’s efforts to ensure the show only features clean, wholesome, family entertainment.

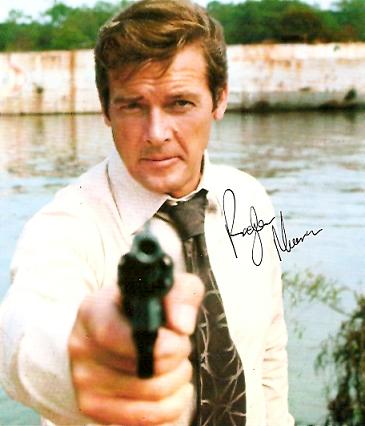

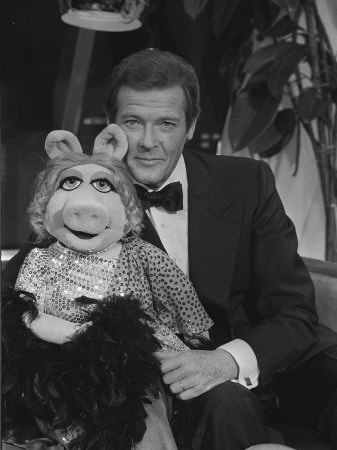

No question, The Muppet Show quickly became a phenomenon. There had been nothing quite like it before, or indeed has there been since; certainly not in prime-time. As with the most popular television entities, its universal appeal ensured it crossed every demographic – at last, Jim, Kermit and their furry friends had cracked it. Just check out their genuinely stellar guest-star list. Every one of the 120 episodes of the show featured a human guest invited on by the Muppets, often to be flummoxed and/ or ridiculed by the fuzzy insanity to which they’re exposed. To begin with, guests included showbiz friends of Henson’s such as actor Joel Grey and musician Paul Williams, only eventually to stretch to everyone from Steve Martin to John Cleese, Elton John to Peter Sellers and Roger Moore (at the height of his Bond fame) to Rudolf Nureyev (twice).

Indeed, the show ensured that in the late ’70s its real stars, the Muppets themselves, became as much a part of the Anglo-American cultural zeitgeist as disco music, punk, Farrah Fawcett posters and, yes, Star Wars (1977). They were everywhere; on music albums, in comic books and on magazine covers. And, it may be fair to say, one of them was beginning to find her way into or – perhaps to be exact – ingratiate herself into people’s hearts more than any other. Before The Muppet Show, Kermit had always been the front-man and while this essentially remained so, especially given he was the show’s first-in-command, as the programme evolved, grew and became ever more popular, he began to share the lion’s share of the limelight with the girl, or rather pig, who appeared to fancy the pointy collar off him.

Miss Piggy’s passionate, brash, judo-kick-packing, all-round diva personality endeared her to peeps across the globe in a way no human counterpart surely ever could. Alongside Kermit, The Muppet Show unquestionably made stars and much loved household names of Fozzie, Gonzo, sidekick Scooter, the lab-based Bunsen and Beaker and maniacal monosyllabic drummer Animal, but Piggy was the one who arguably became one of the faces – if not one of the blonde bombshells – of the 1970s and, in addition to her would-be frog lover, the face of the Muppet brand.

.

But were Kermit and Piggy really an item? This question and others – most pertinently where each of the major Muppets actually came from and how they all originally met – were answered thanks to the gang’s next next logical step. In fact, as it was a proper Hollywood flick, it was really a giant leap. The Muppet Movie (1979) was made and released at the height of the show’s popularity – and reaped the rewards. It’s a film that’s unsurprisingly wacky (its narrative uses the film-within-a-film device and the ‘fourth wall’ is broken more than once), absurdist (one character hands another the film’s script at one point), surprising (Kermit is shown riding a bicycle and others drive cars) and full of songs (its signature tune The Rainbow Connection won a Grammy and a Golden Globe and was nominated for an Oscar). A costly venture for backer Lew Grade at a price-tag of $28 million, it made its money back and more by pulling in $77 million at the box-office, ensuring it wasn’t just the seventh biggest money-spinner of its year, but also that more Muppet movies would inevitably follow.

With a taste for filmmaking now, Henson and Kermit and co. knocked The Muppet Show on the head in 1981 (going out at the top is always better than when in decline, after all) and focused practically full-time on the movie business. That same year the London-set, heist-themed The Great Muppet Caper came out, to be followed three years later by the similar madcap adventure hokum that was the Broadway-based The Muppets Take Manhattan. If these two sequels weren’t quite as well received by critics as their predecessor, they still raked in the moolah, making a combined total of over $55 million from ticket sales.

Henson also struck out on his own, as it were, with the $40 million-grossing The Dark Crystal (1982), a more adult-oriented fantasy adventure featuring neither humans nor Muppets, but Gelfings, and with modernised fairytale Labyrinth (1986), which starred an unforgettable David Bowie and a young Jennifer Connelly alongside many Muppet-like creatures. Surprisingly, at the time Labyrinth wasn’t brilliantly received (both the public and the critics found they could leave it rather than take it), but nowadays it’s arguably more fondly recalled than The Dark Crystal, boasting a fan base that’s more mainstream than the latter’s undeniably cult following.

Apparently, the relative failure of Labyrinth plunged Henson into a genuine low, not that it necessarily should have. For if, by the mid-’80s, his cinematic ventures may have taken a mis-step, his (and the Muppets’) TV efforts were still very much on song. Launched in 1983 and filmed in the UK but broadcast throughout the world, kids fantasy show Fraggle Rock (1983-87), featuring a race of cuddly, Muppet-like, subterranean creatures, became an instant hit and today is rightly looked back on with enormous nostalgia. Similarly, the weekend-morning children’s animated series Jim Henson’s Muppet Babies (1984-91), with its re-imagining of the major Muppet stars as toddlers together in a nursery (as they had been previewed, in fact, in The Muppets Take Manhattan), proved a long-running spin-off success that spawned its own merchandise, including soft toys and comics.

Happy triumphs; heartfelt tribute: Fraggle Rock’s circle of friends (l), the commemorative statue of Kermit and Henson at the University of Maryland (m) and cartoon Muppet Babies (r)

However, after having launched several more TV projects and contributing to the realisation of the turtles themselves for the live-action box-office hit Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1990), Henson’s long, illustrious career came to an end. And, frankly, in the most tragic way imaginable. At the age of just 53, Jim Henson died on May 16 1990 from organ failure owing to contracting an extremely rare, fatal bacterial infection – he had first felt unwell just 12 days before. The show business community on both sides of the Atlantic, indeed, across the world, greatly mourned his passing. He was a visionary, a revolutioniser and then giant of family entertainment; someone who surely deserves to be spoken of in the same breath as Walt Disney.

Yet, despite the loss of their mentor, the Muppets went on. In 1992, under the direction of Jim’s eldest son Brian, they starred in The Muppet Christmas Carol. It may have been released by Disney, but it’s wholly a Muppet venture and, to my mind, terrific – indeed, nowadays it seems to be well on the way to being considered a classic yuletide flick. Featuring Michael Caine as Scrooge (who agreed to be involved apparently because all his friends had already worked with the Muppets), it’s full of familiar furry faces, but pulls no punches; it’s a more faithful adaptation of Charles Dickens‘ timeless tale than countless other efforts.

Spurred on by this success, there was real Muppet momentum again in the mid-’90s as Brian Henson and the gang teamed up again to produce Muppets Tonight (1996-98), a sort of updating of The Muppet Show with star guests such as Michelle Pfeiffer and Pierce Brosnan. They then adapted Robert Louis Stevenson’s pirate fable as Muppet Treasure Island (1996) – to even greater financial success than Christmas Carol – and followed this up with Muppets From Space (1999), in which Gonzo’s origins were finally explained (yes, he’s an alien).

Then, in 2004, Disney took the plunge fully and bought the Henson family company (formerly Muppets Inc., now The Jim Henson Company). Unfortunately, having now made this acquisition, for much of the ’00s Disney didn’t really seem to know what to do with its new employees. Small-screen specials, TV movies and straight-to-DVD flicks came and passed, but there was a feeling that the giant studio was somewhat squandering the talent it had at its fingertips in the shape of its Muppet friends. Occasional guest-star appearances on prime-time shows on both sides of the pond suggested they were still greatly loved – not just by older peeps who grew up with them, but by young ‘uns too – thus, there was still undeniably an audience for the Muppets ready, willing and waiting for another big-time project – if The House Of Mouse could find one that fitted.

Indeed, by the end of the decade several Internet-based efforts underlined this fact. Already the web-series Statler And Waldorf: From The Balcony (2005-06) had gone down well with the ‘Net crowd and then an awesome Muppet-ified video of Bohemian Rhapsody (see video clip below) went down a storm, while Muppet pastiches of notorious print ads and film posters made waves across cyberspace.

And now it feels like it’s 1979 all over again (well, it is a time of austerity with a Tory government once more, ahem); no, what I mean is there’s a new Muppet movie out in cinemas everywhere, making millions and pleasing the punters and the critics in equal measure. Is it any good? Well, I can’t answer that question, as I’m yet to see it (and will, as mentioned, review it here when I do), but the word of mouth certainly says it is. Like any and surely every Muppet fan, I’m damn well excited because it’s time to play the music, it’s time to light the lights, it’s time to meet the Muppets – yet again. But then, it’s hardly as if they’ve really been away. How could they have been? They’re the Muppets; they’re just too darn well legendary.

.

Selected Muppetography:

(All made by Muppets Inc./ The Jim Henson Company; those asterisked officially feature Muppets)

TV shows

Sam And Friends (1955-61)*

Sesame Street (1969-present)*

Hey, Cinderella! (1970) (TV special)*

The Frog Prince (1971) (TV special)*

The Muppets Valentine Show (1974) (Pilot for The Muppet Show)*

The Muppet Show: Sex And Violence (1975) (Pilot for The Muppet Show)*

The Muppet Show (1976-81)*

John Denver And The Muppets: A Christmas Together (1979) (TV special)*

Fraggle Rock (1983-87) (later animated)

Rocky Mountain Holiday With John Denver And The Muppets (1983) (TV special)*

Jim Henson’s Muppet Babies (1984-91) (animated)*

The Christmas Toy (1986) (TV special)*

A Muppet Family Christmas (1987) (TV special)*

The Storyteller (1988/90)

The Jim Henson Hour (1989)*

The Muppets At Walt Disney World (1990) (TV special)*

Dinosaurs (1991-94)

Dog City (1992-95) (animated)

Secret Life Of Toys (1994)

Gulliver’s Travels (1996)

Muppets Tonight (1996-98)*

Bear In The Big Blue House (1997-2007)

Farscape (1999-2003)

Films

The Muppet Movie (1979)*

The Great Muppet Caper (1981)*

The Dark Crystal (1982)

The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984)*

Sesame Street Presents Follow That Bird (1985)*

Labyrinth (1986)

The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992)*

Muppet Treasure Island (1996)*

Muppets From Space (1999)*

The Adventures Of Elmo In Grouchland (1999)*

Kermit’s Swamp Years (2002) (Direct-to-video)*

It’s A Very Merry Muppet Christmas Movie (2002) (TV film)*

The Muppets’ Wizard Of Oz (2005) (TV film)*

A Muppets Christmas: Letters To Santa (2008) (TV film)*

The Muppets (2011)*

Internet

Statler And Waldorf: From The Balcony (2005-06)*

The Muppets: Bohemian Rhapsody (2009)*

The Muppets Kitchen With Cat Cora (2010)*

.

Sketches (etc.) of Boz: happy 200th birthday, Charles Dickens

What dreams may come: Dickens, aged 49, photographed by George Herbert Watkins in 1861

By a quirk of sheer Dickensian fate, if any day could be chosen for the bicentenary of arguably the world’s – certainly Blighty’s – master storyteller, then surely it should be today. Here, in the south-east of England (including, of course, that city forever and rightly associated with him, London), all is covered in snow. It’s also bitterly cold and the night doubtless will be misty and dark as a black blanket too. In short, it’s a dramatic and rather melancholic winter’s day, and yet what with the snow, very atmospheric and almost wistful. It’s a Dickensian day all right.

Yes, that’s right, chaps, Chuck Dickens is 200 years old – or, at least, he would be if (admittedly bizarrely) he were still alive. And, not least because he’s my favourite novelist (and, to my mind, the best that ever laid pen to paper) and thus an enormous inspiration to me as a budding novelist, methinks it’s only right on such a whimsically flavoured blog as this to mark the occasion and – through extracts scribbled by him, images featuring him and, yes, video clips of scenes based on his works – celebrate his exceptional efforts.

He may have, according to biographer Claire Tomalin, led a private life that ensured his wife suffered in silence, but he also possessed an extraordinary, unsurpassed talent at creating not just great comic and/ or grotesque characters and at weaving into his writing (sometimes satirically, often starkly) the all too urgent need for social reform in his society, that of Victorian Britain. Not everyone dug him (both Virginia Woolf and Henry James disliked his supposed sentimentality and implausibility), but almost everyone else, both in and beyond his lifetime, rate him quite rightly as one of the greatest writers who ever lived.

So, on the event of your 200th, here’s to you, Boz – indeed, let’s all drink to Dickens, shall we, from a cup of the milk of human kindness; it’s the least the great man deserves…

.

“Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show” ~ from David Copperfield

.

Go west, young man: Dickens, aged 30, by Francis Alexander in 1842, during his first US tour

.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.” ~ from A Tale Of Two Cities

.

.

“It is a fair, even-handed, noble adjustment of things, that while there is infection in disease and sorrow, there is nothing in the world so irresistibly contagious as laughter and good humour” ~ from A Christmas Carol

.

Victorian vignette: a group captured by an unknown photographer in 1857 including Dickens (front row, sitting sideways) and his great friend and fellow acclaimed author Wilkie Collins (front row, head leaning forward) (National Portrait Gallery, London)

.

“You are part of my existence, part of myself. You have been in every line I have ever read, since I first came here, the rough common boy whose poor heart you wounded even then. You have been in every prospect I have ever seen since – on the river, on the sails of the ships, on the marshes, in the clouds, in the light, in the darkness, in the wind, in the woods, in the sea, in the streets. You have been the embodiment of every graceful fancy that my mind has ever become acquainted with. The stones of which the strongest London buildings are made, are not more real, or more impossible to displace with your hands, than your presence and influence have been to me, there and everywhere, and will be. Estella, to the last hour of my life, you cannot choose but remain part of my character, part of the little good in me, part of the evil.” ~ from Great Expectations

.

.

“She was the most wonderful woman for prowling about the house. How she got from one storey to another was a mystery beyond solution. A lady so decorous in herself, and so highly connected, was not to be suspected of dropping over the banisters or sliding down them, yet her extraordinary facility of locomotion suggested the wild idea.” ~ from Hard Times

.

Gone but not forgotten: Dickens surrounded by characters from his works and, below, his chair, empty – compiled by an unknown artist and an unknown photographer and commissioned in 1872 following his death two years previously (National Portrait Gallery, London)

.

“No one who can read, ever looks at a book, even unopened on a shelf, like one who cannot” ~ from Our Mutual Friend

.

.

Charles Dickens selected bibliography:

(All are novels – originally published in weekly or monthly serials – unless otherwise stated)

Sketches By Boz (fiction and non-fiction pieces, 1833-36)

The Pickwick Papers (1836-37)

Oliver Twist (1837-39)

Nicholas Nickleby (1838-39)

The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41)

Barnaby Rudge (1841)

A Christmas Carol (novella, one of the ‘Christmas Books’, 1843)

Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44)

The Chimes (novella, one of the ‘Christmas Books’, 1844)

The Cricket On The Hearth (novella, one of the ‘Christmas Books’, 1845)

The Battle Of Life (novella, one of the ‘Christmas Books’, 1846)

Dombey And Son (1846-48)

The Haunted Man And The Ghost’s Bargain (novella, one of the ‘Christmas Books’, 1848)

David Copperfield (1849-50)

Bleak House (1852-53)

Hard Times (1854)

Little Dorrit (1855-57)

A Tale Of Two Cities (1859)

Great Expectations (1860-61)

Our Mutual Friend (1864-65)

The Signal-Man (short story, 1866)

The Mystery Of Edwin Drood (unfinished, 1870)

.

Further reading:

The ‘Dickens And London’ exhibition at The Museum Of London (until June 10)

.

Playlist: Listen, my friends ~ February 2012

In the words of Moby Grape… listen, my friends! Yes, it’s the (hopefully) monthly playlist presented by George’s Journal just for you good people.

There may be one or two classics to be found here dotted in among different tunes you’re unfamiliar with or have never heard before – or, of course, you may’ve heard them all before. All the same, why not sit back, listen away and enjoy…

.

CLICK on the song titles to hear them

.

Sammy Davis Jr. ~ The Second Best Secret Agent In The Whole Wide World¹

Georgie Fame ~ The Ballad Of Bonnie And Clyde

The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band ~ The Intro And The Outro

Electric Light Orchestra ~ 10538 Overture

The Simon Park Orchestra ~ Eye Level²

Shirley Bassey ~ Something

Julio Iglesias ~ La Mer¹

Odyssey ~ Native New Yorker

Tangerine Dream ~ Love On A Real Train³

Herbie Hancock ~ Rockit

Echo & The Bunnymen ~ The Killing Moon

Kate Bush ~ Brazil⁴

Eric Clapton ~ Bad Love

.

¹ As featured in the film Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

² The theme from the Dutch-set, British TV detective drama Van Der Valk (1972-77/ 1991-92)

³ From a most memorable sequence in the movie Risky Business (1983)

⁴ From the soundtrack of the film Brazil (1985), although this version of the song didn’t feature in the movie itself

Bubble trouble: Patrick McGoohan unsuccessfully eludes his psychedelic balloon-esque pursuer, ensuring decade-defining drama The Prisoner continues, befuddling and delighting viewers

Last summer and autumn, across a trilogy of posts, this very blog treated its visitors (read: allowed me to indulge in sharing) my thoughts on the essential films released in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. And now this winter it’ll be bringing you three posts along exactly the same lines, except this time they’ll all be focusing on offerings from that slightly smaller screen: the gogglebox.

So, kicking us off then, let me present to you, dear readers, my dectet of ultimate TV shows from the decade of The Beatles and civil rights; Swinging London and flower power; the Profumo Affair and spy-fi – yup, it’s the ’60s, peeps, and here’s their 10 ultimate televisual delights…

.

CLICK on the TV show titles for video clips

.

The Ed Sullivan Show (1948-71)

Why not start this list with perhaps the greatest TV moment of the 1960s? It occurred on February 9 1964, was broadcast on the US network CBS and was watched by an estimated 73 million people – that’s 45 percent of all US households at the time. It was of course The Beatles’ first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, an event that has gone down in the annals of Twentieth Century cultural history. The Ed Sullivan Show will be forever remembered because of, nay defined by, this individual night in its long run, but in fact was really a product of the ’50s rather than the ’60s, its first edition being broadcast way back in June 1948. Originally named Toast Of The Town, it became an immovable object in its Sunday night slot (8-9pm ET) – the variety show to appear on if one wanted to make it as a national star. And so it was that The Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein was only too eager for his charges to appear on the show on three consecutive Sunday nights (February 9-23) during their first US tour. It’s said there wasn’t a crime committed anywhere in the US during their first appearance – a rather ridiculous urban myth, but a wonderful one. No question, The Ed Sullivan Show was far from the most groundbreaking TV programme of the ’60s, but its ubiquity ensured that with The Fabs’ appearances, the ‘British Invasion’ of pop music truly took place in the States. And acts no less than The Supremes, The Beach Boys, The Lovin’ Spoonful, The Doors, The Rolling Stones and, yes, The Muppets would follow their lead and guest on the show in order to launch themselves across the US as well.

.

The Avengers (1961-69)

Many would assume it was James Bond’s fault and in many ways it was, but the TV drama genre that gave rise to the term ‘spy-fi’ (a portmanteau of ‘spy’ and ‘sci-fi’) actually hit small screens a whole year before Bond hit the big screen. It all started with Brit adventure series The Avengers, which debuted on ITV in January 1961. Yet, to begin with, the ABC Television-produced show was quite different to the inimitable hit sold to 90 different countries it evolved into. Although it featured Patrick Macnee from the off as series hero John Steed, the character then was a tough guy rather than the impossibly debonair, bowler hat and umbrella-packing toff he indelibly became. And, at first, his co-star wasn’t a woman; it was a vengeful male doctor. Surviving his first series, Steed was joined by a female sidekick thereafter: Honor Blackman’s judo-kicking, leather-clad Cathy Gale in series two and three, Diana Rigg’s unforgettable proto-feminist Emma Peel in series four and five and Linda Thorson’s curly haired heroine Tara King in the final series). It’s the Emma Peel era that’s most fondly recalled, though, and rightly so, for this was when the show hit its stride. Coinciding with the Swinging Sixties – and the show going colour in the States thanks to US money – the chemistry between Macnee (channelling Edwardian nostalgia) and Rigg (decked out in Mod fashions) was electric; their old-meets-new collision complementing the increasingly zany plots (invading alien plants and pet cats becoming vicious killers) and the incorrigibly self-referential, off-kilter, witty tone. A glut of spy (or spy-fi) TV drama followed in the ’60s, of course, and all of it was inspired by The Avengers – and even some in the ’70s, an example being The New Avengers (1976-77), the successful follow-up in which Macnee returned for more hokum with the lovely Joanna Lumley as his new sidekick Purdy.

~~~

That Was The Week That Was (1962-63)

It seems rather an odd notion, but there was a time when British politicians were unthinkingly respected, nay deferred to. That all came to a crashing end in the early ’60s and one of the game-changers was a new breed of unrepentant satire. With former Cambridge Footlighters Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett and Jonathan Miller making waves in Soho theatre revue Beyond The Fringe, the cosily conservative BBC took an uncharacteristically bold step and got in on the act. The brainchild of producer Ned Sherrin, That Was The Week That Was (or TW3, as its sort of abbreviation went) showcased many of the hottest satirists working the cabaret circuits. Fronted by now legendary TV behemoth David Frost (but then a fresh-faced, prickly wit), it also featured bright young things Willie Rushton, Lance Percival, Millicent Martin – who performed the show’s opening theme tune – and provocative political brain Bernard Levin. Fortuitously arriving just in time for the nation-gripping ‘Profumo Affair’ (TW3 debuted in November ’62; the scandal ran throughout the following year), the live show enjoyed huge audiences for its Saturday night timeslot – more or less the equivalent of Match Of The Day‘s today – as around 12 million people tuned in each week for its blend of entertainment and scathing attacks on the Establishment penned by everyone from Keith Waterhouse (author of Billy Liar) to Dennis Potter (soon-to-be TV dramatist par excellence) and Gerald Kaufman (future Labour MP) to Graham Chapman (who’d be a Monty Python before the decade was out). Quite simply, the style, format and tenor of every satirical TV/ radio broadcast since has owed an inestimable debt to That Was The Week That Was. However, like so many great artistic ventures, it didn’t last long; the Beeb pulled the plug months before the February ’64 General Election claiming the show could be seen to jeopardise the corporation’s political impartiality and affect the result.

~~~

Ready Steady Go! (1963-66)

Not everyone in the early to mid-’60s was moving to the beat drummed by satire, though; increasingly, young ‘uns were moving to the beat drummed by, well, Beat music. Driven by the – more or less – Liverpool-hailing ‘Merseybeat’ groups (The Beatles, Gerry And The Pacemakers) and their contemporaries from in and around London (The Rolling Stones, The Who, The Kinks and The Small Faces), it was the white-hot new face of rock ‘n’ roll and thus was prime for promotion/ exploitation by the TV people. This time, however, it was ITV rather than the BBC that struck gold. Ready Steady Go! first hit screens in August ’63 and immediately became hip, must-see viewing up and down the country. Going out on Friday early-evenings with its tagline ‘The weekend starts here!’, it helped boost the careers of up and coming pop/ rock artists, while making others’, as they performed chart hits in a cramped-looking studio space filled with lucky fans. The show also made a star of its best recalled host, a girl named Cathy McGowan who was plucked from obscurity. McGowan quickly became a favourite with viewers, as she was clearly just as much a fan of the acts as the audience at home, lending her an authentic air and natural appeal. She would go on to become one of the icons of Swinging London; her ordinariness but good looks ensuring she was perfect as a model of the latest Mod fashions. In 1965, the show’s producers took the smart move of insisting acts should perform live, which only made it even more essential viewing, but by the end of the following year Ready Steady Go! was no more; ITV bosses decided its time had passed as the ‘Beat boom’ was now over and the show was cancelled at the height of its popularity. Still, its legacy is obvious and unquestioned – in January ’64 the Beeb had taken the plunge and launched Top Of The Pops… and the rest, as they say, is history.

~~~

Till Death Us Do Part (1965-68 and 1972-75)

By the mid-’60s, the cultural and political landscape satirised in That Was The Week That Was had changed. Harold Wilson’s Labour was in power and, like in the States (but to a lesser extent and to a lesser furore), civil rights legislation was being passed, reflecting a society that seemed to be becoming more liberal by the day. Yet, although in reaction the Tories had now ditched the toffs at the top for the grammar school-educated Ted Heath, far from all Tory-leaning folk were changing with the times. To dramatise this fast changing and confused Britain, the BBC made a surprising choice – it made a sitcom. Admittedly, with the wildly popular Steptoe And Son (1962-65 and 1970-74), the Beeb had already used a sitcom to explore the divide developing between the generations in political and social views, specifically when it came to the working class, and this it did again in Till Death Us Do Part, but the difference between the former and latter is that the latter made its point with a sledge-hammer. In the shape of middle-aged, right-wing and racially bigoted East-Ender Alf Garnett, ace comedy scribe Johnny Speight created a central character for his sitcom that was so well observed by actor Warren Mitchell that some in society (those who, well, agreed with his views) didn’t realise the show’s intention of showing him and his views up. But the majority, even if they felt his language and no-holds-barred depiction went too far (such as ‘Clean Up TV’ campaigner Mary Whitehouse notoriously did), still realised the joke was always on him. Till Death Us Do Part was hugely successful, its original run comprising three series until it returned for four more in the early ’70s, after which came two cinematic escapades in ’69 and ’72 and a relaunch by ITV in 1981 under the name Till Death…, before Alf returned to the Beeb in follow-up In Sickness And In Health (1985-92).

~~~

Batman (1966-68)

Unlike their British counterparts, the US TV networks weren’t quite adventurous enough yet to represent ‘reality’ in their dramas and comedies. Instead, reacting to an ever growing youth consciousness and the counter-culture, they turned to youth-driven escapist fantasy and three shows of this nature became not just hits but iconic cultural gems whose popularity has far outlived the ’60s. The first was based on classic comic book character Batman. Nowadays, thanks to the darkness of his ’80s, ’90s and ’00s movies, we tend to think of Batman as a social misfit avenger operating in a cruel, violent world, but back in the day ABC’s Batman TV series presented the caped crusader and his youthful sidekick Robin inhabiting a universe perfectly defined by a single word: camp. Conceived by ABC as an answer to NBC’s hip spy-fi series The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (1964-68), Batman originally was intended to balance its comedy and drama, but the result was a cocktail of OTT characters in boldly coloured costumes and spouting witty, satirical dialogue in incredibly hammy plots. Yet the camp didn’t end there. Not only did each half-hour episode conclude with a cliffhanger in which the heroes were caught in a ‘deathtrap’ (complete with a voice-over: ‘Tune in tomorrow – same Bat-time, same Bat-channel!’), but the fight scenes were embellished by comic book-esque, superimposed onomatopoeic words (‘POW!’, ‘BAM!’, ‘ZONK!’). Batman was a big ratings hit for the first two of its three seasons (for its third it became even more surreal and topically referenced hippies and Mods), ensuring a ‘Bat-craze’ broke out across America – the toy ‘Batmobile’ led a huge merchandise drive – and a movie was released in the summer of ’66. For today’s Christopher Nolan fans, this Batman may be anathema, but Adam West’s antics still hold a soft spot in the hearts of millions of others.

~~~

Star Trek (1966-69)

The legacy of the second of the three youthful US fantasy dramas on this list is indisputable (it’s the most influential sci-fi TV series of all time), but ironically, unlike Batman, the ‘original series’ of Star Trek wasn’t an unflappable, Vulcan-like ratings winner. Conceived by creator Gene Roddenberry as ‘Horatio Hornblower in space’ (referencing the Napoleonic-era naval hero of C.S. Forester’s books), the show may not have pulled in the high audiences hoped for by its network NBC, but built up a dedicated following among educated teenagers and young adults – so much so a highly organised letter campaign led by Californian university students secured the show its third and final series. This fanbase would grow during the ’70s, of course, to create the phenomenon of ‘Trekkies’, ensuring Star Trek enjoyed numerous repeats on TV making it the cult, nay enormously popular, TV show that would spawn blockbuster movies and follow-up small-screen series. However, despite its discovery in the years after its original broadcast, Star Trek indefatigably remains a product of ’60s America. For, while Roddenberry produced a naval-esque space adventure show, he also deliberately used the futuristic sci-fi setting to push the envelope of American TV drama. For the escapades of the unforgettable trio Kirk, Spock and MCoy (and their fellow crewmates) actually explored hot topics of the time such as racism, sexism, nationalism and global war – a fact clearly not lost on the show’s cerebral audience demographic. Indeed, Star Trek is famous for featuring American television’s first fictional interracial snog (between Kirk and sexy comms officer Uhuru), an event that made waves at the time. Yup, it was one show that pretty much did boldly go where no other had gone before.

~~~

The Monkees (1966-68)

The last of the trio of youth-oriented US fantasy shows was just as popular as the other two and remains as ground-breaking and influential as any other on this list. Inspired by The Beatles movie A Hard Day’s Night (1964), Hollywood wannabes Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider conceived a sitcom featuring the anarchic antics of a make-believe rock ‘n’ roll quartet, who’d perform songs in each episode and whose members would be played by unknowns (Mickey Dolenz, Mike Nesbit, Peter Tork and Englishman Davy Jones). With its avant-garde production techniques – loose narratives, improvisation, jump-cuts and those song breaks (which, as in The Fabs’ own films, prefigured the music video) – The Monkees was a huge success with the youth audience with which its makers (and NBC) had hoped it would strike a chord. The Monkees themselves were striking chords of another kind too, as backed by Columbia Records the would-be band became a real one off the back of the show, scoring hit singles on both sides of the Atlantic. All seemed sunny in manufactured-band paradise (the show’s first season picked up a pair of Emmys and The Monkees clearly had genuine musical talent), but the stars soon tired of the rigours of TV production and wanted more artistic freedom, ensuring the second season was the last. The band’s time in the sun set soon afterwards too, but not before they’d starred in a psychedelic ‘head film’ called, er, Head (1968) that deconstructed the show’s universe. Also made by Rafelson and Schneider, it wasn’t a success; unlike the two’s next project together: producing iconic counter-culture flick Easy Rider (1969). After which they teamed up again for the multi Oscar-nominated Five Easy Pieces (1970). And, to this day, Rafelson says all he threw into making these classic ‘New Hollywood’ movies, he learnt, yes, from making The Monkees.

~~~

Cathy Come Home (1966)

In stark contrast to the hottest dramas on US TV, back home the Beeb was still pushing naturalistic and social issue-led drama to new levels. And in 1966, it broadcast a drama that pushed the genre so far it may never have been topped since. Cathy Come Home was a one-off piece shown that November in The Wednesday Play anthology. This strand had already gained a reputation for featuing prevalent social issues, but by ’66 its new controllers producer Tony Garnett (now a UK TV legend) and young director Ken Loach decided to push it further still – as The Wednesday Play followed BBC1’s evening news bulletin, they wanted each new drama to feel like a continuation of the news rather than a work of fiction. Cathy Come Home unquestionably fulfilled that aim, as it followed the fall of a couple into poverty, eviction and homelessness. But what really made it hard-hitting and revolutionary was its unorthodox filming style. Many of its scenes were improvised, featured documentary-esque voiceovers, were captured using hand-held cameras and employed quick editing, ensuring a current affairs programme-style. It was viewed by an enormous 12 million people and the moment every single one of them remembered was its ending, when Cathy has her children taken away from her by social services. To say this scene, filmed in a railway station and featuring unwitting on-lookers as extras, is powerful is a genuine understatement. Unlike the on-lookers, though, the general public did at least intervene – following its broadcast, Cathy Come Home caused such a sensation it was discussed in Parliament and its notoriety helped launch the homeless charities Shelter and Crisis. It didn’t do Ken Loach any harm either, as three years later he went on to make the acclaimed feature-film Kes and, to this day, remains Britain’s foremost issues-driven filmmaker.

~~~

The Prisoner (1967-68)

And so to this list’s final entry – and it’s surely the quintessential ’60s TV show. Despite being popular, The Prisoner wasn’t among the most viewed TV shows of that decade, nor was it the longest running or the most ubiquitous. What it was, though, was a fantasy drama (produced by UK television company ITC for ITV) that tapped into many themes prevalent in ’60s (counter-)culture: collectivism versus individualism, identity theft, hallucinogenic drug experiences and control through internment, intimidation, indoctrination and mind control. Conceived by its star Patrick McGoohan and – to a greater or lesser extent – by writer George Markstein, it may or may not have been a sequel to Danger Man (1960-62 and 1964-66), a series in which McGoohan starred as a similar character. In the latter the protagonist was an active spy; in The Prisoner he’s a former employee of the British government (most likely a spy) who after resigning is imprisoned in a village, seemingly for the powers-that-be to break him and discover what secrets he may know. However, during the show and even following its final episode, all that’s up in the air. The thing with The Prisoner (and no doubt one of the reasons why it remains so popular) is that what’s going is never clear. Throughout, the audience is no wiser – or even less informed – than The Prisoner himself (or ‘Number 6’ as he’s known). It’s surely safe to say, though, that The Prisoner was a 1984 for the pop culture-informed, spy-fi-entertained 1960s generation, what with its Mini Mokes, big white escapee-chasing balloon and lava lamps. Spread across two series, 17 episodes of the show were filmed, mostly in the Italianate Portmeirion village resort of North Wales, which for decades now has been beseiged by Prisoner fans obsessed with the show’s Orweillian themes, Mod-ish designs and Penny-farthings. Most other peeps aren’t obsessed with The Prisoner, but almost all of them have at some point revelled in trying to work out just what the hell it’s all about – much like with the 1960s themselves, you might say.

~~~

Five more to check out…

The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (1964-68)

Mentioned above, America’s take on 007 (whose protagonist Napoleon Solo – fact alert – was invented by Ian Fleming, inventor of 007 himself)

Not Only… But Also (1964-70)

Peter Cook and Dudley Moore’s popular post-Beyond The Fringe sketch show, famous for its musical interludes and guest appearances from John Lennon

Thunderbirds (1965-66)

Gerry Anderson’s puppet-based hit fantasy adventure series – read more here

Adam Adamant Lives! (1966-67)

The Beeb’s answer to The Avengers, featuring an Edwardian hero in surreal, oh-so Swinging Sixties, crime-fighting adventures

Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968-73)

US sketch comedy fondly recalled for introducing Goldie Hawn to the world and so popular that, by not appearing on it when his Republican rival Richard Nixon did, Democrat candidate Hubert Humphrey claimed he lost the ’68 Presidential Election

~~~

… And five great TV shows about the ’60s

Happy Days (1974-84)

Whimsical sitcom revolving around the lives of late ’50s/ early ’60s Milwaukee adolescents

The Wonder Years (1988-93)

Nostalgic dramedy set in the late ’60s and early ’70s focusing on the growing pains of everyday American kid Kevin Arnold

Quantum Leap (1989-93)

Time-travel drama in which Scott Bakula’s Dr Sam Beckett jumps in and out of others’ bodies in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s

Our Friends In The North (1996) (Warning: this link contains strong language)

Excellently observed, epic drama serial following the lives of a quartet from Newcastle, beginning in the mid-’60s

Mad Men (2007-present)

Universally acclaimed drama set in the early to mid-’60s world of New York’s Madison Avenue advertisers